The Jordanian monarchy’s social contract with its population is fraying, leading to protests and discontent among youths, and a rumored recent coup attempt has seen King Abdullah II quickly moving to solidify his control over the country. With Jordan poised to become an even more important U.S. ally in an unstable region, its future stability will likely depend on domestic reforms and external assistance from benefactors such as the U.S.

As a country geographically located at the crossroads of several conflict zones, Jordan is strategically important to the United States, as is its stability. Looming over this relationship is the question of whether there will be a cohesive Jordanian society left by the time King Abdullah II passes the mantle of leadership over to his son, Crown Prince Hussein. The aftermath of a rumored April coup attempt by King Abdullah’s half-brother, Prince Hamzah, shows that the Jordanian security apparatus and the country’s foreign backers continue to prefer the king’s line of succession, meaning the monarchy is not yet in danger.

However, the rentier state of patronage that forms the basis of the social contract between the country’s Hashemite rulers and the Jordanian population, especially the tribes, is tattering. The challenge to the Jordanian system is how to sustainably expand opportunities for a restless rising generation of unemployed or underemployed Jordanians, beyond college age but under the age of 40, who cannot start their careers, get married, and start families, or hope for a better future.

The Jordanian system was initially built around the notion that a noble tribal lineage not indigenous to the Trans-Jordan region – the Hashemites – could serve as an intermediary and “sheikh among sheikhs,” directing resources appropriately to maintain the loyalty of a nation composed mainly of rival tribes. Jordan at its creation was a relatively sparsely populated, predominately rural country, and the system thus was not built to weather the modern Jordanian state’s challenges, including successive waves of in-migration from decades of regional conflicts, especially by Palestinians; the urbanization of formerly rural or nomadic populations such as the Bedouins; and the commensurate decline in social and economic quality of life for the indigenous population. Where trade and exchange of goods once dominated the relationship between the urban and the rural in Jordan, a new competition for resources replaced the old contract. The socioeconomic bugbears of Jordan – the high cost of living, poor wages, lack of employment, lagging social and political rights, and corruption – and the added hardships of the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in persistent protests over the last few years.

The Jordanian state has shown significant resilience in its history, largely because of generous foreign security assistance dating back to British support for the Hashemite-led Great Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Empire during World War I. What began as a British intelligence operation to weaken the Ottoman Empire metastasized over three decades into a client state that was organized around the idea that Trans-Jordan could be not just a geographic space but a key partner nation for the West in a geopolitically critical world region. This idea remains at the heart of the modern U.S-Jordanian partnership.

For its part, Jordan has been able to transfer this foreign aid into both “guns and butter”: Security assistance has allowed the state to maintain well-trained and effective internal security forces mainly drawn from the tribes, and international development aid has generally supported the communities from which these forces are mobilized.

The Jordanian monarchy has conventionally been viewed as distinguished and different than other Middle East royal families. The king and queen have been perceived as being more approachable and more deeply connected to the mainstream society of Jordan than their counterparts in the Gulf and Morocco, for example. This perception applies to how authoritarianism is defined in Jordan as well. While not a democracy, crackdowns and oppression of free speech in the kingdom have generally been less brutal than in other kingdoms. However, in the wake of the March protests, the kingdom is adopting an increasingly oppressive approach to dissent, opposition, or calls for reform, meaning the “exceptionalism” of the Hashemite monarch could be tested. The current system in Jordan appears to lack a strategy to address the growing concerns and discontent of the youth.

The tribes, too, are feeling the pressure of a changing social dynamic that no longer favors them. Since the so-called “Ramadan protests” in Jordan in 2018, there have been increasing incidents of symbolic violence directed at the state, and by extension the monarchy, such as burning tires and closing off security forces’ access to towns. Many of these actions have been performed by tribal communities that are losing faith in the viability of their compact with the Hashemites. These protests are, to a large extent, a reminder to the state (and the monarchy), that the phrase Allah, Al-Watan wal-Malik (God, Nation, and King) means that the tribes are the ultimate source of support and power of the regime – and that they can also take that power away.

A large part of Prince Hamzah’s appeal was his outspoken declaration of support for a movement to renew this social contract and expand its coverage for the millions of Jordanians of the “settling down” age who are feeling left behind. This appeal, in addition to the potential waning of the current royal family’s exceptionalism, seems to have compelled King Abdullah to take swift measures against his half-brother. The social contract (which often excludes Jordanians of Palestinian heritage) may never be renewed because of the burdensome cost of lifetime patronage to tribal elites; foreign lenders’ demands for austerity measures, such as cutbacks in state employment, especially in the military; and the Jordanian economy’s inability to expand fast enough to guarantee the shortfalls in the rentier patronage system.

The Jordanian state has thus far prevented another Black September-like uprising. Aiding the monarchy currently are two factors. First, regional instability has left potential protesters wary that an attempted overhaul of the status quo could cause the same kind of state collapse that befell Syria and Iraq. Second, Jordan’s status as an armed camp for its foreign backers would seem to make the prospect of a successful armed uprising even more difficult. Nevertheless, no amount of foreign security assistance can indefinitely push away a collapsing economy, a disappointed and increasingly desperate population, and a now open question whether there can ever be sustainable economic and political reform to a state that was built as mechanism for rentier patronage. This is the conundrum of the Hashemites.

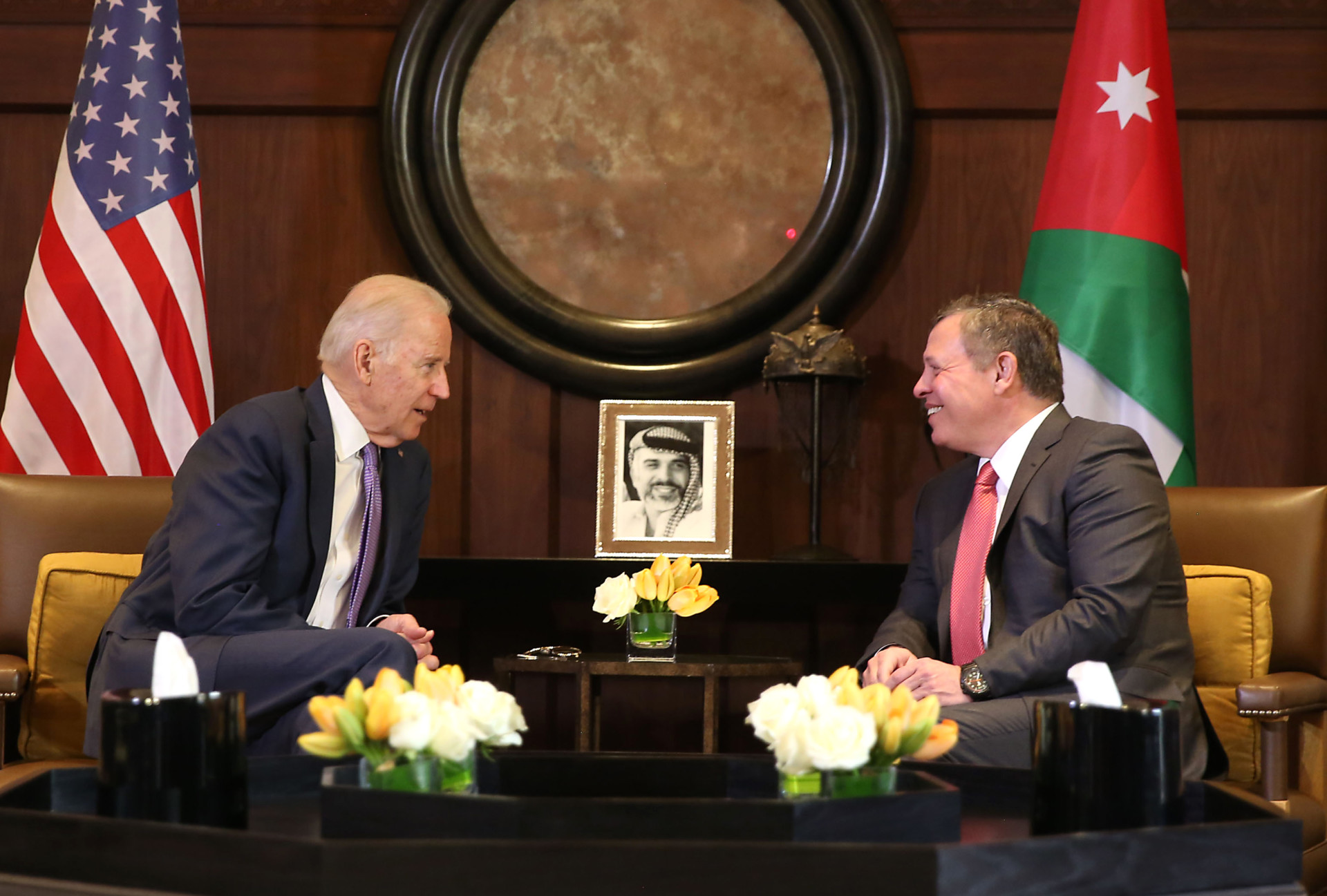

Currently, the U.S. is repositioning strategic military assets for the U.S. Central Command area of responsibility from Qatar to Jordan and is making it apparent that Jordan has renewed importance for U.S. global strategy. Jordan’s opposition to the previous administration’s peace plan, and the threat that it could lead to the formation of an “alternate homeland” for Palestinians in Jordan, should be alleviated by the Biden administration’s commitment to a two-state solution between Israel and Palestine. This renewed support from the U.S. should reassure Jordan’s leaders, but it is insufficient in addressing the social and economic realities in the Hashemite Kingdom that could impact its long-term stability. Jordan’s future stability will likely depend on political, social, and economic reform that is closely tied to external security and economic assistance from benefactors such as the U.S. This careful process of internal reform, paired with external assistance, might be the only way to fulfill King Abdullah’s vision to pass on a stable constitutional monarchy to his successor.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of the Newlines Institute.