Listen to article

After more than a month of saber rattling from Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan over northern Syria, the U.S.-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) on July 6 declared a state of emergency in anticipation of a possible third Turkish offensive in the region. U.S. and Russian calls for de-escalation appear to have forestalled an immediate invasion. Although some Turkish proxies released images and statements in early June indicating that they were mobilizing, these signs of preparation have tapered off in recent weeks, and on July 1, Erdoğan told reporters there was “no need for hurry” on a new operation.

It is too soon to say whether Turkey’s planned offensive has been averted or merely delayed, but a slower-burning crisis persists in the area, with Turkish proxies and SDF affiliates engaged in tit-for-tat strikes along the front lines, killing both soldiers and civilians. Even if the death and displacement that would result from a new Turkish campaign are averted, this ongoing pressure hurts civilians and leaves the SDF less able to rein in other actors in its own territory. Washington has demonstrated in the past that it can play a constructive role in preventing a major flare-up of the conflict. It now has an opportunity to turn its attention to the lower-intensity fighting that has degraded the security situation in northeast Syria over the past year.

Turkey’s Goals

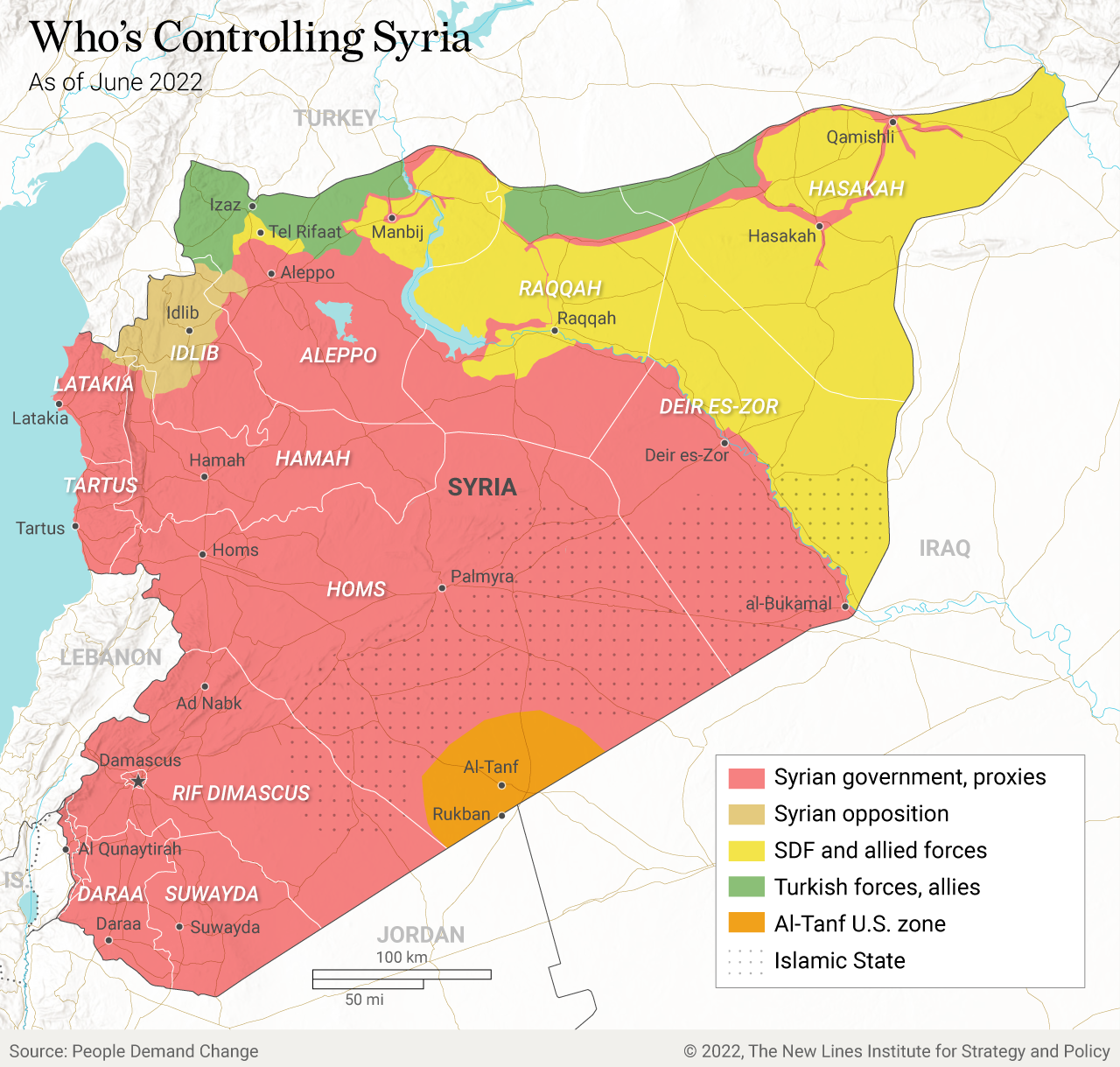

The possible operation, per Erdoğan’s comments, would seek to establish a 30-kilometer (about 19-mile) buffer zone across northern Syria, which has been a stated goal of Ankara’s since 2019. On June 1, Erdoğan identified two key targets of the opening phase of the campaign: Tel Rifaat and Manbij, whose location on the periphery of the SDF’s zone of control would make them the hardest for the SDF to defend.

A new Turkish offensive could dramatically alter the front lines of Syria’s civil war, which have been largely static since an October 2019 cease-fire deal ended Turkey’s Operation Peace Spring into SDF-held territory. When it was signed, Turkey and its proxy militias were left with a patchwork of territory across northern Syria, including most of the territory within 30 kilometers of the Turkish border west of the Euphrates, as well as a new 30-kilometer buffer zone extending into previously SDF-held territory east of the river. The cease-fire left the SDF and its affiliates maintaining a complicated, often-violent front line with Turkish proxies across northern Syria. Tel Rifaat, an isolated pocket of SDF-aligned territory west of the Euphrates, was left in a particularly tense situation, and regular artillery shelling and drone attacks have destabilized the front line near Manbij and in the SDF’s core territory east of the Euphrates.

This is not the first time that Ankara has threatened a new offensive that failed to materialize. In October 2021, when Erdoğan blamed Kurdish fighters for the death of two Turkish police officers in Syria, he called it the “final straw” and signaled that a new campaign to seize territory from the SDF was imminent. Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu said the country would do “what is necessary” to eliminate threats against the territory held by its proxies in northern Syria, as some of those proxies appeared to mobilize and prepare for a new round of intense fighting. Within a month – and after heavy U.S. and Russian pushback – Turkey appeared to quietly back down. With no green light from either Washington or Moscow, Ankara was unwilling to weather the economic and diplomatic blowback of attempting to shift the front lines of the conflict.

This was in sharp contrast to the events that preceded Turkey’s Operation Peace Spring in 2019, when Turkey and its proxy forces pushed the SDF out of much of the territory it once held along the border. That operation was preceded by a phone call between Erdoğan and then-President Donald Trump, coupled with a series of statements by the White House reiterating that the United States was accelerating its timeline to withdraw from Syria completely. Perceiving no serious opposition from Washington, Ankara moved quickly to seize as much territory as possible along its border in an operation that displaced over 100,000 civilians and threatened to cause the collapse of the entire SDF, until the White House intervened diplomatically to negotiate a cease fire.

The diverging outcomes highlight Washington’s important role as a security guarantor in northeast Syria. Although the war in Ukraine has drawn both Russian and U.S. attention away from Syria and potentially has left Ankara feeling it has more freedom to operate there, Turkey has demonstrated in the past that it is eager to expand its occupation of northern Syria when it feels it has Washington’s tacit approval but is much more circumspect when the White House signals a clear and unambiguous commitment to its security partners in northern Syria.

Continuing Violence in Northern Syria

Regardless of whether Turkey launches a new offensive – and despite the 2019 cease-fire agreement – smaller-scale violence continues along northern Syria’s front lines. The Turkey-backed Syrian National Army launched an attack and artillery strike on SDF-held positions June 6, and a separate attack June 11. On June 27, the White Helmets alleged that shells launched from SDF-held territory near Manbij injured two civilians. And on June 28, the pro-Kurdish Rojava Information Center provided evidence that Turkey had launched four drone attacks into SDF-held territory in under 24 hours.

Given the number of armed groups acting within these territories, it is rarely possible to decisively attribute individual attacks to specific parties, but is clear that territory held by both Turkish proxies and the SDF is being used to launch regular attacks against rivals and civilians alike. These attacks are not a recent phenomenon; within 12 months of the October 2019 cease-fire that ended Operation Peace Spring, CFR Fellow Amy Austin Holmes had identified over 800 violations of the agreement by Turkey and its proxies, including violence against both the SDF and civilians – an average of 2.3 violations per day.

The fighting has both humanitarian and strategic implications. Indiscriminate shelling, and in some cases apparently deliberate attacks, are killing civilians, damaging civilian infrastructure, and impeding freedom of movement – when checkpoints become a regular flashpoint for conflict, civilians are less able to trade and travel outside their neighborhoods.

Strategically, the effects are more nuanced. Turkish drone, artillery, and missile strikes whittle away the SDF’s limited strength, forcing the group to redirect its attention away from ISIS and other armed groups operating in its territory. As northeast Syria becomes an increasingly prominent smuggling route for captagon and other narcotics, the SDF will face hard choices in how much of its limited manpower to allocate to address the powerful armed actors within SDF territory who are facilitating this trade, among other threats to local and regional stability.

In the long term, increased Turkish pressure may lead to more profound realignments. When Erdoğan threatened his most recent offensive, the SDF’s leadership responded in part by saying that the group would turn to President Bashar al-Assad’s regime and its allies for assistance defending its borders, just as it did during Operation Peace Spring. Although the move may be unpalatable to those in Washington still seeking to hold the regime responsible for its atrocities, including mass executions, indiscriminate aerial bombardment, and the use of chemical weapons, the group has few realistic choices to thwart a renewed attack from Ankara, given Washington’s unwillingness to engage in direct fighting with a NATO ally.

With or without a new offensive, the SDF will continue to face strong pressure to lean on outside powers for manpower and materiel for continued fighting on the front lines. The SDF’s key request of the Assad regime in early June was for air defense equipment. With Turkish drone strikes continuing unabated, the group is likely to see that equipment as a strategic priority even if Ankara does not seek to alter the front lines.

Policy options

Although Russian pressure may have given Turkey pause about launching a new offensive in northern Syria, the United States retains far more military and economic leverage in the country’s northeast, leaving it best positioned to mediate disputes between the SDF and Ankara. Washington has demonstrated that with enough resources and multilateral engagement, it can avert major escalations in the fighting in northeast Syria, but the threat of renewed offensives will be a perennial problem if lower-level fighting remains endemic. Neither Turkey nor the SDF are willing to accept a security situation where the territory they hold is regularly shelled, and actors on both sides of the front line have responded to attacks with their own retaliatory fire.

No one party can solve this problem on its own, but Washington could start by raising the profile of these attacks. Although Erdoğan’s threats of a new offensive were met with emphatic, repeated condemnation by U.S. President Joe Biden’s administration, these lower-level attacks across the front lines are rarely addressed in official briefings or statements by U.S. policymakers. The United States retains enormous leverage over the SDF as its primary security guarantor and can communicate in clear terms that its security assistance to the group is predicated on a commitment to de-escalation and a willingness to investigate credible claims of civilian harm.

While Washington’s leverage over Ankara is more limited, U.S. security assistance to Turkey is considerable and currently undergoing scrutiny in Congress. Both the White House and Capitol Hill have an opportunity to communicate to Ankara that avoiding a new offensive is a first step, rather than the end goal, for stability in northeast Syria.

This pressure by Washington could reduce shelling, drone strikes, and other forms of violence along the front lines, but in the long term, a durable cease-fire needs to be negotiated between the two sides. The current cease-fire agreement, signed in October 2019, is vaguely worded and lacks enforcement mechanisms. Moreover, it was negotiated bilaterally between the White House and Ankara, with only haphazard engagement by the SDF and other actors on the ground, due to the urgency and chaos of the then-ongoing Operation Peace Spring. It was not meant to ensure long-term peace and stability in northeast Syria.

The exact form and substance of a new deal is not up to Washington, but policymakers should seek opportunities to play a constructive role in mediating cease-fire disputes and, to the extent possible, work to bring both sides together to negotiate a credible, durable, and enforceable agreement. Without one, violence is almost certain to continue, and that violence will in turn create pressure on both sides to escalate in ways that may be irreversibly destabilizing for the region.

Calvin Wilder is an Analyst for the Nonstate Actors program at the New Lines Institute. Prior to joining the New Lines Institute, Calvin was a Research Assistant at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy’s Program on Arab Politics. He previously worked as a Research Assistant on the Chicago Project for Security and Threats (CPOST)’s Arabic Propaganda Analysis Team, and he was a Boren Scholar in Amman, Jordan from 2019-2020, working as a research and translation intern at Syria Direct. He holds a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science from the University of Chicago. He tweets at @CalvinWilder.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of the New Lines Institute.