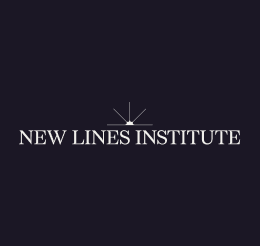

The world is currently experiencing a record number of armed conflicts, affecting an estimated 2 billion people. Youth, defined by the United Nations Security Council as individuals between the ages of 18 and 29, are part of the largest generation in human history, forming the majority in many conflict zones, but they are routinely marginalized by political processes. More than half of the world’s population is under 30 years old, but only 2.2 percent of parliamentarians are under 30, and less than 1 percent are young women. Governments around the world are failing to tap into youth as a valuable resource for new solutions to a wide range of existing and emerging security challenges, thereby missing crucial opportunities for innovation, prosperity, and stability.

U.N. Security Council Resolution 2250, adopted unanimously in December 2015, formally recognized the positive role young people can play in conflict and post-conflict settings and linked their involvement to the maintenance of international peace and security under Chapter 7, Article 39 of the U.N. Charter. This resolution, and follow-on resolutions adopted in 2018 and 2020, form the Youth, Peace, and Security (YPS) agenda. Despite the growing recognition of the agenda’s relevance, the U.S. government has not yet capitalized on its potential to serve as a critical lens for more agile and effective foreign policy. The current administration should codify U.S. commitment to YPS and implement this underutilized foreign policy framework throughout the U.S. government to support more effective policymaking and a more resilient world.

Origins of the YPS Agenda

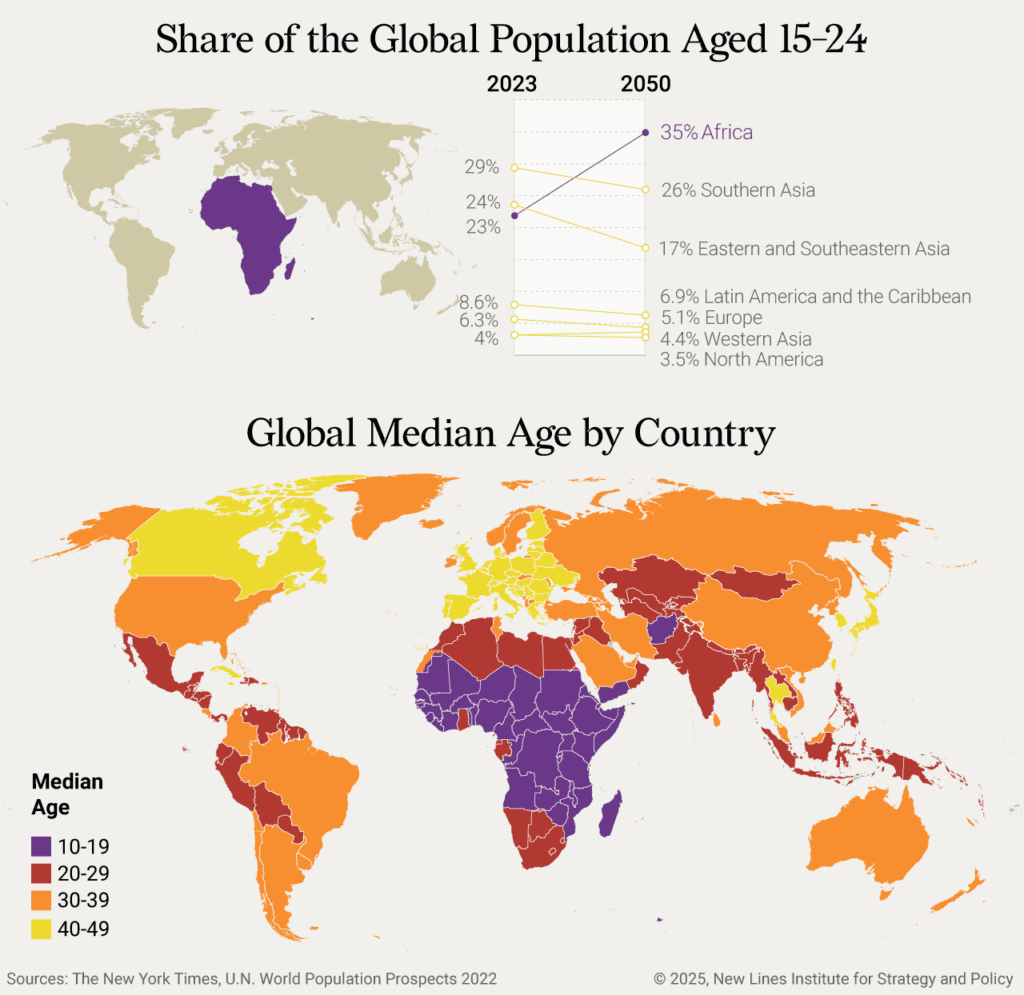

The YPS agenda was the product of civil society advocacy that challenged the dominant narrative around youth in conflict zones, which portrays young men as security threats and young women as victims. These organizations emphasized that young people are not inherently violent and, to the contrary, can be effective agents of peace. Further, they identified a policy opportunity to engage young people proactively in peace and security processes rather than approaching youth from a position of policy panic. Youth activists called upon the U.N. and its member states to examine the structures that marginalize youth peacebuilders and to take an active role in promoting meaningful youth inclusion in peace and security processes. Resolution 2250 outlined five pillars of youth participation:

Resolution 2250 directed the U.N. secretary-general to commission an independent study on the potential for youth to contribute positively to peace processes and conflict resolution, and in 2018, this report was published under the title, “The Missing Peace.” The study documented the violence of exclusion experienced by young people around the world and noted the structural barriers to their participation in political processes and in peace and security discussions more broadly. The report noted that policies and programs informed by YPS must account for the experiences of young men and women thoughtfully and equitably, including through deeper understanding of masculinities.

Following the release of this report, the Security Council adopted Resolution 2419 (2018), “recognizing that [youth] marginalization is detrimental to building sustainable peace and countering violent extremism,” and Resolution 2535 (2020), specifically calling on U.N. peacekeeping operations and special political missions to integrate YPS into the operational planning and activities of U.N. field missions, with protection considerations at the forefront. Resolution 2535 also tasked the U.N. secretary-general with regular reporting on the status of the implementation of the YPS agenda, which took the form of status reports in 2022 and 2024.

Parallels to Women, Peace, and Security

The Women, Peace, and Security (WPS) agenda, initiated through Resolution 1325 (2000), is more widely known and broadly implemented than YPS, though there is still a long way to go to achieve the goals outlined in this framework. It is the WPS agenda’s primary objective to promote the full, equal, and meaningful participation of women in peace and security processes, where they are profoundly underrepresented; to address the specific impacts of conflict on women; and to empower women as agents of peace and stability, with benefits for people of all backgrounds. The operationalization of WPS has led to increased women’s participation in the security and governance sectors around the world, contributing to more durable peace agreements and improved situational awareness, better early warning systems, and greater operational effectiveness in U.N. peace operations. Both the WPS and YPS agendas established frameworks for more broadly representative peace and security processes and more durable solutions to conflict, and both are largely unenforceable without the coordinated and committed action of national governments.

The agendas are complementary, and many of the initiatives they drive can be mutually reinforcing. The Canadian Coalition on YPS has had some success advancing the YPS agenda through existing WPS commitments, as YPS supports the civic participation of women and girls; however, the YPS agenda is not merely a facet of WPS. WPS and YPS are co-equal agendas addressing structural barriers to participatory (and therefore, effective) peace and security processes, but they differ in focus and approach.

While it may be pragmatic to advance YPS through existing WPS commitments, it is important to avoid creating the perception that YPS exists only in service of WPS. The pursuit of YPS solely though the WPS agenda undermines the strategic value of YPS. In the advancement of both WPS and YPS, it is worth considering:

- How the mainstreaming and operationalization of YPS can help facilitate the participation of women and girls in the security sector

- How the advancement of the WPS agenda can support and inform progress on youth-oriented policymaking and programming

- How these two agendas could be leveraged to create the greatest benefit to U.S. national security and international peace and security

- How governments and international organizations can institutionalize these agendas to better harness human potential for peace, prosperity, and global stability

In the past year, several U.N. Security Council events have been dedicated to elevating the role of women and youth in responding to global crises, including a U.S.-hosted signature event titled, “Investing in the Transformative Power of Intergenerational Leadership on Women and Peace and Security.” By highlighting the strength of intergenerational partnership to further WPS action, the event acknowledged the strength inherent in the YPS framework without referencing it explicitly. However, by highlighting intergenerational partnership only as a means of advancing WPS, the event missed an opportunity to elevate YPS and recognize the role of men and boys in advancing both agendas.

Institutional Commitment to YPS

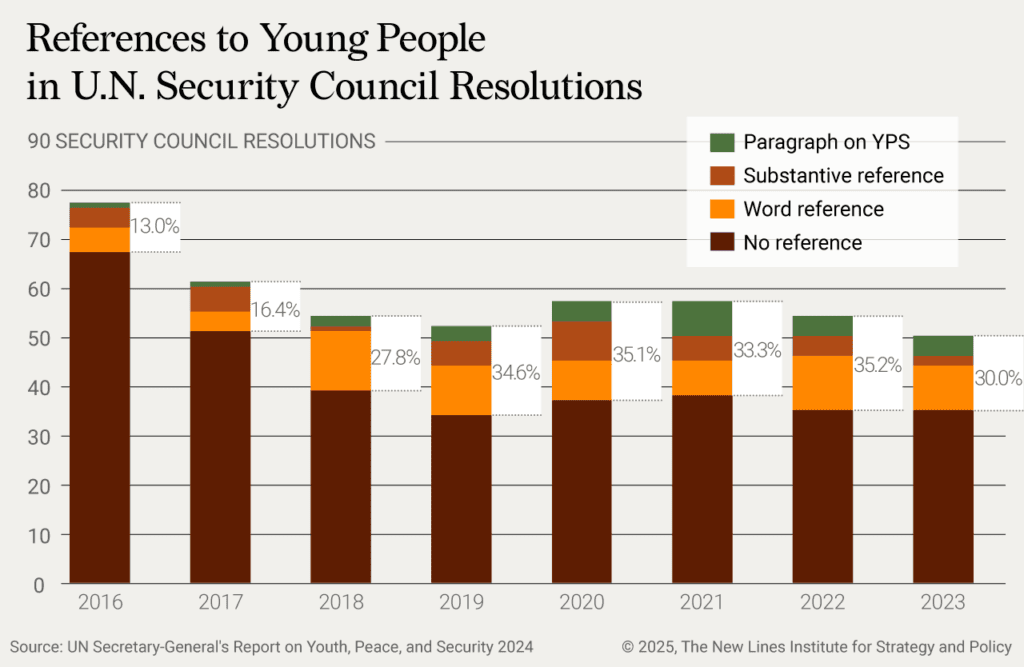

In alignment with the direction outlined by the Security Council, the U.N. has made efforts to institutionalize the YPS agenda by appointing youth envoys, including Ahmad Alhendawi in 2013 and Jayathma Wickramanayake in 2017. In 2023, U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres appointed Felipe Paulier as the first assistant-secretary general for youth affairs. This step further solidified youth issues as a strategic priority for the U.N. and accordingly established leadership serving in a more permanent capacity. U.N. member states have also identified the advancement of YPS as a strategic priority, including it as an action item in the Pact for the Future; however, fulfillment of these goals is voluntary, and member states have historically displayed weak commitment to implementation and a lack of recognition of the relevance of YPS to the topics addressed through U.N. Security Council resolutions.

U.N. efforts to coordinate YPS implementation remain relatively decentralized and underfunded, creating missed opportunities to optimize youth engagement. YPS operationalization across U.N. agencies is also hindered by a shortage of dedicated funds, relying instead on the voluntary contributions and political will of member states. In addition to uneven member state commitment, YPS implementation is limited by the difficulties youth-led organizations experience in competing for and accessing existing U.N. funds.

U.S. Institutionalization of WPS and YPS

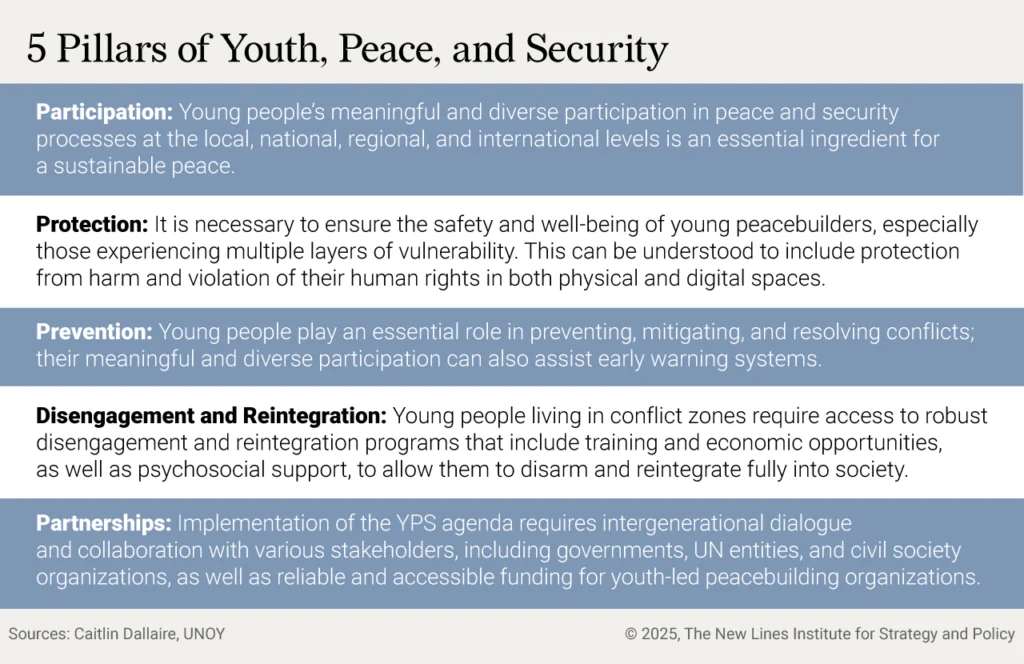

The WPS agenda has been advanced globally through the proliferation of a series of National Action Plans. The United States, having adopted a National Action Plan on WPS in 2011, was the first country to adopt a comprehensive law on WPS in 2017. The WPS Act of 2017 established WPS as a domestic and foreign policy framework and directed the creation of coordinated strategies to ensure the comprehensive implementation of the agenda through an array of federal agencies. The law has been successful in increasing the participation of women in the peace and security sector and in negotiated peace agreements around the world. It has driven progress in the Department of Defense to integrate WPS into policies, plans, doctrine, training, and education, and it has contributed to the expansion of partnerships between the U.S. and other like-minded governments. Most importantly, national legislation elevated WPS as a strategic priority; educated the federal workforce on the direct link between WPS and operational effectiveness; and facilitated the coordination of federal policies and programs for maximum effect.

YPS has yet to be implemented in earnest or institutionalized within the U.S. government. Democratic and Republican administrations have appointed youth envoys and coordinators such as Andy Rabens and Abby Finkenauer at the State Department and Mike McCabe and Sarah Sladen at the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID); however, the State Department envoys were tasked with public diplomacy outreach and given no real policy mandate by the department. Without a mandate or sufficient resources to coordinate youth policy, particularly Youth, Peace, and Security implementation, State Department envoys have promoted youth leadership globally but have not been given the resources or the mandate to institutionalize a cohesive YPS strategy in the U.S. government.

Congress has seen three bills related to YPS implementation, all of which have had bipartisan support. The first bill, introduced in 2020, identified the Department of State as the lead agency in coordinating a whole-of-government strategy to implement YPS in conflict prevention and mitigation efforts. The third bill, H.R. 5024, was introduced in 2023 and directed USAID to serve as the lead agency on YPS through a USAID-appointed youth coordinator supporting “cross-sectoral international development efforts related to youth, inclusive of youth, peace, and security, and for other purposes.” USAID’s progress and vision regarding the implementation of YPS is captured by the Youth in Development Policy and reflected in the 2023 draft legislation; however, to maximize the impact of YPS as a foreign policy framework, U.S. policymakers should focus on the advancement of youth participation in all facets of decision-making regarding peace and security, not limited to development work, however that is conceptualized going forward.

By limiting the scope of YPS to international development efforts, the latest draft legislation failed to capture the strategic value of YPS as a broader U.S. foreign policy framework with the ability to drive a whole-of-government application of YPS principles to policies and programs in conflict-affected countries. The marginalization of the YPS agenda – its reduction to a subcategory of WPS or a facet of foreign policy limited mainly to development – reflects the marginalization of youth and leads the U.S. to fall short of its obligations under the three internationally agreed and legally binding Security Council resolutions. Future legislation will need to account for drastic changes to USAID and the streamlining of government under the current administration. Under these circumstances, there is an even greater need for a whole-of-government strategy to build resilience and stability around the world through a future-oriented approach to global security challenges.

YPS Applied to U.S. Foreign Policy

The YPS agenda has been endorsed through a U.N. Security Council vote but not yet implemented by the U.S. government. The agenda supports objectives outlined in several existing U.S. strategies, including: the U.S. Strategy to Prevent Conflict and Promote Stability (required by the Global Fragility Act); the U.S. Strategy and National Action Plan on Women, Peace, and Security; the U.S. Global Strategy to Empower Adolescent Girls; the U.S. International Cyberspace and Digital Policy Strategy; and the Democratic Roadmap to Build Civic Resilience to Global Digital Information Manipulation Challenges, to name a few. As a policy framework, the YPS agenda could serve as a force multiplier for U.S. efforts to counter violent extremism, respond to the threat of mis- and disinformation, promote democratic resilience, and counter geopolitical competitors.

Without legislation and resources from Congress or an executive order calling for a National Action Plan, the agencies that create and carry out U.S. policies and programs in conflict-affected countries (particularly the Department of State, USAID, and the Department of Defense) lack the mandate to implement YPS. Without a policy mandate, adequate education and resources, or any shortage of competing priorities, these agencies – particularly State and Defense – have failed to consistently apply YPS principles to their work, even though much of this work in conflict zones serves or impacts youth. In other words, the U.S. government is doing YPS-oriented work as a part of its response to conflict without a strategy to harmonize these efforts and maximize their effectiveness.

The YPS agenda also opens avenues for stronger bilateral partnerships, especially with Global South/global majority countries, many of which have demonstrated their investment in YPS through the development of national strategies. The African Union, which developed a Continental Framework on YPS in 2020, calls upon its membership to develop NAPs in recognition of the fact that inclusion supports resilience and stabilization; therefore, U.S. implementation of the YPS agenda creates opportunities for an Africa policy that is more reflective of and responsive to the aspirations of the African people. Young leaders in Latin America have embraced the agenda and developed networks designed to promote innovation, stability and resilience at the community level, demonstrating the potential for YPS to enrich U.S. efforts to address security challenges in the Western Hemisphere. The EU has made progress in implementing YPS, and a handful of countries have developed and launched National Action Plans, while around 60 more currently have plans in development.

The full implementation of the YPS agenda would support a more future-oriented U.S. policy toward many of these countries and drive U.S. policymakers to advocate more consistently for young people’s participation in peace negotiations, providing a foundation for more durable agreements. This could soon be relevant in so many contexts, from Syria to Sudan, to the DRC, and Gaza, where agreements that do not reflect the views of young people or secure their endorsement are much less likely to succeed.

The Cost of Non-Implementation

There is a growing body of evidence to support the social, economic, and political value of the YPS agenda. A 2023 USAID and civil society study found that for every dollar invested in young peacebuilders, there is a $10 return on that investment. Preventing, mitigating, and ending conflict more quickly and more effectively through youth-informed processes reduces the need for U.S. taxpayer dollars to support costly military interventions, reduces the need for foreign assistance, and creates opportunities for new and expanded economic partnerships. For example, the recent protests driven by Kenyan youth in response to a controversial finance bill, cost the private sector upwards of $20 million per day, underscoring the economic impact of unrest and the need for proactive policymaking that is responsive to the concerns of young people.

Recommendations to U.S. Policymakers

- Congress should revise and adopt legislation that:

- Reflects the need for meaningful youth participation in a broad scope of peace and security activities

- Requires the Secretary of State to appoint a sufficiently resourced and capacitated YPS coordinator to advance the implementation of the agenda within the State Department and enhance interagency collaboration

- Requires the departments of State and Defense to draft and publish a strategy for promoting youth-informed peace and security processes and youth-inclusive development practices that promote resilience rather than dependency

- Provides the necessary resources for the development of institutional capacity within the U.S. government to sustain youth-focused policymaking in conflict-affected countries

- Acknowledges the reality that youth play a role in preventing and responding to conflict, and therefore, young people in countries that are not presently affected by conflict can also be peacebuilders

- The White House should include Youth, Peace, and Security as a component of the new National Security Strategy and articulate the benefits of broadly representative and therefore durable peace processes for U.S. national security, international security, and global economic development.

- In lieu of legislation, the White House should work toward an executive order, developed in consultation with young peacebuilders, instituting a National Action Plan on Youth, Peace, and Security.

- The National Security Council should include a youth advisor equipped to encourage YPS considerations in the NSC’s coordination of foreign policy among the relevant government agencies.

- The Department of State, USAID, and Department of Defense should pursue the following activities, regardless of progress on legislation or a National Action Plan:

- Capacity: Create permanent institutional capacity within each agency to coordinate youth-oriented policies in the peace and security pillar

- Educating and Mainstreaming: Integrate foundational elements of YPS into onboarding, training, and continuing education for all public servants, both career and political appointees, in domestic and overseas assignments

- Coordination: Engage in interagency coordination to drive the implementation of YPS through bilateral and multilateral channels

- Leadership: Advance U.S. leadership on YPS at the U.N. and in other multilateral fora through a variety of means, to include:

- Advocating for language in the mandates for peacekeeping missions and special political missions, and supporting the allocation of resources oriented toward YPS implementation at U.N. field missions during U.N. 5th committee budget negotiations

- Hosting U.N. Security Council sessions on challenges related to international peace and security with a youth lens and/or elevating youth perspectives

- Reenergizing the Group of Friends on YPS at the U.N.

Conclusion

The YPS agenda has great strategic value as the United States attempts to strengthen ties and counter competitors that are exploiting security gaps and exacerbating instability around the world, particularly in the Global South – an area already vulnerable to climate insecurity, governance issues, and other conflict exacerbators. Therefore, it would be in the United States’ national interest to apply a YPS lens and integrate YPS principles into all policies and programs at their inception and to use this lens continuously as a tool for analyzing the effectiveness of policies, programs, and other interventions. At minimum, the Department of State should appoint dedicated capacity to lead interagency coordination, in concert with the relevant agencies, in the development of a plan to apply the YPS agenda as a strategic framework to new and existing initiatives. This should occur regardless of the pace of legislation. Finally, the Trump administration should advance a national YPS initiative in 2025 in commemoration of the 10th anniversary of the YPS agenda and in recognition of the fact that doing so builds resilience and enhances U.S. national security and advances peace, stability, and prosperity around the world.

Cait Dallaire is a Non-Resident Senior Fellow at the New Lines Institute and an expert on the Youth, Peace, and Security (YPS) and Women, Peace, and Security (WPS) agendas. Prior to joining New Lines, Dallaire served as a foreign affairs officer at the U.S. Department of State, advising on U.N. peacekeeping operations and broader U.N. Security Council issues. Dallaire co-founded the department’s YPS working group and authored the Bureau of International Organizations’ YPS strategic roadmap. Her background includes work on disinformation, climate security, and other issues affecting U.N. field missions. Dallaire holds a Master of Science in International Security from East Carolina University and a Bachelor of Arts in International Studies from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of New Lines Institute.