As Mexico’s two-decade war against drug cartels has worn on, cartel tactics have evolved. The groups have begun to focus not just on moving drugs to the United States but also on controlling territory inside Mexico, which has led to intensified inter-cartel battles and the groups’ increased militarization. Cartels now operate more like insurgent groups than purely criminal organizations, employing tactics such as improvised explosive devices (IEDs), drones, and the recruitment of foreign mercenaries, specifically from Colombia. As of May 2024, cartels controlled about one-third of Mexico’s territory.

This evolution is a direct security threat to Mexico, the United States, and regional stability, and it demands a commensurate shift in policy. Mexico must continue to strengthen its security institutions, and the United States, as Mexico’s most critical security and economic partner, must fundamentally reorient its policies to address how the flow of U.S. weapons fuels cartel violence.

From Criminal Networks to Militarized Groups

Cartels’ militarization has increased as they have expanded from purely transactional goals to territorial ambitions. Nathan P. Jones, an associate professor of security studies at Sam Houston State University and author of “Mexico’s Illicit Drug Network and the State Reaction,” said in an interview that transactional cartels are “more focused on the arbitrage of the drug business, the logistics of trafficking, and making a profit exclusively through those means. In short, they move drugs from point A to point B, buy and sell, and make their money that way.” The Guadalajara Cartel, the main Mexican cartel responsible for smuggling marijuana and cocaine into the United States from 1980 – 1989, embodied this operational model. It prioritized shipping drugs to maximize profit rather than to exert overt territorial control.

On the other hand, “Territorially oriented groups make profit from controlling their territory. This leads to a diversification of criminal activities into things like extortion, kidnapping, sex and labor trafficking, and smuggling, but also passing drugs through their territories and charging other groups for the privilege. Because this requires more personnel to patrol and control a territory, they become more hierarchical because more management is required, and there are larger payrolls to meet. This model also tends to become much more predatory because it focuses on making profit from what goes on in the local area.” The Zetas Cartel, which were known for their sheer violence and enforcement of the territories they operated in, followed this model.

The transition to a more territorial focus has enabled Mexico’s cartels to be less dependent on drug trafficking, which then requires a more militarized force. Cartels thus are now engaged in an intrastate conflict over territorial control, mostly against rivals. Such battles are easily documented on messaging groups and social media channels that cover regional cartel violence in Mexico, where the use of up-armored vehicles and drones dropping explosives is a common occurrence. Jones pointed out “an increase in territorial business models and an overall homogenization of the tactics, techniques, and procedures of organized crime in Mexico. The intense competition for territory has led to the adoption of new technologies such as drones and likely innovations such as the use of fiber optic cables to control them.”

The violence impacting Mexico comprises multiple concurrent conflicts in which the Mexican government is at times not the main combatant. These include:

- The Sinaloa Cartel Civil War: Two factions of the Sinaloa Cartel, the Mayito Flacos and Los Chapitos, are currently battling for control of the state of Sinaloa. Forces under leader Ismael “Mayito Flaco” Zambada currently control southern Sinaloa, while Los Chapitos are centered around the state capital of Culiacán. Los Chapitos recently announced an alliance with their historical rival, the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG), and CJNG fighters have launched offensives along the border of Sinaloa and Durango against Mayito Flaco-associated factions.

- The Gulf Cartel Civil War: Multiple factions of the Gulf Cartel are fighting for control of Tamaulipas, with the two main groups being the Metros, out of Reynosa and Grupo Escorpión out of Matamoros. The factions currently maintain a tenuous ceasefire after years of fighting.

- Mayito Flaco and CJNG Conflict: Mayito Flaco and CJNG are currently engaged in multiple territorial battles spanning Sinaloa, Nayarit, Jalisco, Durango, Zacatecas, and Chiapas.

- CJNG Michoacán Offensive: CJNG is currently on the offensive in Michoacán, fighting against two cartels, the United Cartels and La Familia Michoacana.

These examples indicate that cartels view rival cartels as a greater threat than the Mexican government. This cartel violence is now being exported to South America, with Ecuador’s gangs having direct connections to both the Sinaloa and CJNG cartels.

U.S. Fuels Cartel Firepower

A key component of cartel militarization is the trafficking of U.S. weapons into Mexico. A recent 60 Minutes report claimed that between 200,000 and 500,000 firearms are smuggled into Mexico from the United States yearly forming what experts called “the iron river.” These weapons often originate from U.S. manufacturers like Smith & Wesson and are funneled through wholesalers and retailers with lax oversight. In response, Mexico filed two lawsuits—one in 2021 against a manufacturer and wholesaler, and another in 2022 against five U.S. gun stores—accusing them of reckless and unlawful practices that enable cartels and other criminals to arm themselves.

The flow of weapons is facilitated by the stark contrast between U.S. and Mexican gun markets. The U.S. has over 75,000 active gun dealers, creating a vast supply chain that is difficult to monitor, while Mexico operates only a single, highly restricted gun store located on a military base in Mexico City. This disparity allows traffickers to exploit the abundance and accessibility of firearms in the U.S., transporting them illegally across the border to fuel organized crime and violence in Mexico.

Analyzing cartel videos and photos regularly published on social media shows that all cartels have a propensity to utilize .50 caliber anti-materiel rifles such as the M82 or M95, which are manufactured in the United States. These rifles often serve as the primary anti-tank capability for cartels, as the use of rocket-propelled grenades is still limited. These firearms have been difficult to defend against, as the Mexican military, National Guard, and police operate in lightly protected vehicles vulnerable to .50 caliber weapons.

Cartel Tactics

Another development is an increase in Colombian mercenaries, especially in Michoacán. Both CJNG and the United Cartels prioritize recruiting Colombian fighters, with special emphasis on those with recent combat experience in Ukraine fighting against Russian forces. By recruiting fighters with extensive combat experience, lessons learned from the Russian-Ukraine War are making their way into Mexico.

In addition, recent reporting shows that the Mexican Center of National Intelligence and the Ukrainian Security Servies are actively investigating the deployment of Mexican cartel operatives to Ukraine Foreign Legion to receive training on the use of drones in an offensive capacity, which are then used in Mexico. With the arrival of such experienced fighters, both CJNG and the United Cartel have expanded the use of drones and continue to develop drone programs. This was demonstrated by an attack on June 9 in which CJNG utilized drones to drop various explosive devices on the municipal building of Juárez, Michoacán. These types of attacks will likely become the norm.

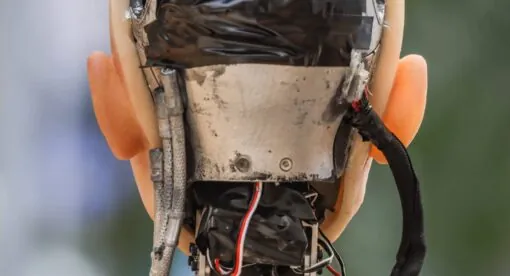

Cartels also regularly us heavily armed and reinforced civilian vehicles known as monstruos that provide protection and firepower during clashes in urban areas. They Mexican cartels also have significantly increased their use IEDs, causing significant civilian casualties. In January, the U.S. State Department issued a an alert advising against travel in Tamaulipas due to the increase of IED usage, including one incident that killed a U.S. citizen.

These capabilities, while formidable, are still nascent, and the Mexican government, with U.S. support, can confront them. Images released by the Mexican military showing seized explosive devices, either IEDs or drone-dropped, show that those capabilities are rudimentary.

Policy Recommendations

This lack of sophistication provides a critical window of opportunity for the United States and Mexico to address the growing threat. Recently, Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum proposed to U.S. President Donald Trump a bilateral “general agreement” over security, migration, and commerce. The current administration should maximize this offer and solidify the United States’ role as Mexico’s primary security partner. A failure to do so could lead to the deterioration of the security environment along the U.S. southern border.

As part of Sheinbaum’s proposal, the United States and Mexico would expand existing military-to-military cooperation between U.S. Northern Command and the Mexican Army and Navy. Specifically, the U.S. would expand bilateral training missions that provide advanced instruction focusing on lessons learned from over 20 years of counterinsurgency operations in the Middle East, such as IED and drone tactics.

Current bilateral training is generally smaller in scale and not consistently scheduled, limiting its effectiveness. Additionally, much of that training focuses on peacetime operations such as humanitarian or natural disaster relief. While this training is important Mexico’s significant internal security problem should be the priority of both countries. Beyond bilateral exercises of limited value, a concerted effort with regular troop rotations either in the United States or Mexico would maximize capabilities.

The U.S. Army should leverage the Security Forces Assistance Brigades (SFABs) for such training missions and should partner with the Mexican Army and Mexico’s National Guard to provide even more robust support. Although Mexico would likely never agree to a permanent deployment of U.S. forces on its soil, SFABs can effectively support Mexican operations from within the United States. Moreover, SFABs are well suited to expanding this mission to include advisory and assistance roles. SFAB units have already successfully partnered with the Colombian military, an effort that can serve as a model for missions in Mexico. Ultimately, a designated SFAB for Mexico would, at minimum, enhance interoperability between both militaries.

Counterinsurgency training should also be provided to Mexican law enforcement agencies at the state and local levels. In most cases, local and state police forces bear the brunt of cartel violence. Although there is extensive law enforcement training and cooperation with their U.S. counterparts, it generally lacks the military component necessary to address these threats. Additionally, Mexican law enforcement agencies regularly operate side-by-side with Mexican military units, further proving the necessity of this training.

Furthermore, the U.S. funding sent to Mexico falls short of what’s needed to meet the growing threat. In the 2025 Annual Threat Assessment of the United States Intelligence Community, Mexican cartels and other transnational criminal organizations were listed as the top threat to the United States, a first for the annual report. But in fiscal year 2024, the Biden administration requested just $127.1 million for Mexico in helping combat drug trafficking organizations, a small percentage of overall foreign aid. Moreover, the budget focused chiefly on countering drug trafficking despite the shift in cartel strategy toward territorial control. The allocation of this aid neither properly empowers Mexican security forces to address cartel militarization nor adequately equips t with vital military equipment. When considering aid allocation, Congress should consider the expanded security threat the cartels constitute rather than continuing to view issues in Mexico solely through a drug or human trafficking lens.

United States also can help prevent Mexican cartel militarization by stymieing the flow of firearms into Mexico. With the recent designation of six cartels as foreign terrorist organizations, the U.S. Department of Justice has expanded tools to indict key weapon smuggling networks that arm Mexican cartels. The U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) needs to prioritize weapon smuggling, as too often U.S. weapons empower criminal organizations to challenge state authorities. This is a regional problem, with multiple Latin American governments highlighting the issue of U.S. weapons in the hands of gangs.

The United States should approach this problem in coordination with regional partners within existing frameworks that combat drug trafficking organization, such as Joint Interagency Task Force South and Joint Task Force North. In addition, the U.S. State Department should acknowledge the role the trafficking of weapons from the U.S. plays in expanding violence across the Western Hemisphere, a constant diplomatic issue in the region. A public commitment from the United States, followed by a concerted effort by the Departments of Justice and Homeland Security, would improve U.S. standing and expand influence with Latin American governments.

A key focus for U.S. law enforcement must be to tackle the arrival of anti-material rifles, such as the M82. The Mexican government has highlighted the role U.S. gun manufacturers play in the arrival of these weapons into cartel hands, and although U.S. law limits punitive measures against such companies, more needs to be done.

The militarization of Mexican cartels is a defining element of the evolving regional security landscape. The United States should ensure that it offers meaningful and adequate training to Mexican security forces and combat the threat of U.S. weapons flooding the Western Hemisphere. As this transformation deepens, Mexico confronts an internal conflict where cartels possess the means, organization, and territorial ambitions akin to insurgent groups. The increasing use of drones, IEDs, armored vehicles, and military-grade weaponry, often sourced from the United States, points to a conflict that extends far beyond the conventional understanding of organized crime.

Conclusion

Expanded military-to-military cooperation, robust intelligence sharing, and a reinvigorated commitment to interdicting the flow of U.S. weapons into Mexico must become cornerstones of bilateral engagement. Simultaneously, U.S. foreign assistance must reflect the complexity of the challenge. Funding strategies that focus solely on drug interdiction are insufficient; territorial control, not drug trafficking alone, drives the cartel business model today. As such the United States should:

What lies ahead is a narrow window of opportunity: Cartels are militarizing, but they have not yet developed the full-spectrum capabilities of traditional insurgent forces. This moment presents a chance to halt further expansion and prevent the normalization of quasi-military conflict on the U.S.–Mexico border. Failure to act decisively could entrench these dynamics permanently, transforming cartels into durable, violent actors capable of destabilizing the Western Hemisphere for decades to come. Haiti is a case example of what can happen south of the U.S. border if cartel militarization is not properly addressed.

This is not just Mexico’s problem. It is a shared regional crisis demanding shared responsibility, and a strategic realignment to meet the emerging threats of the 21st century.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of New Lines Institute.