In this episode of Eurasian Connectivity, Kamran Bokhari hosts Nicole Hark, country director for Syria at Mercy Corps, for a discussion of the country’s humanitarian situation, particularly in its northeastern and northwestern regions, where her group’s operations are concentrated.

Kamran Bokhari:

Hello everyone. Welcome to another episode of Eurasian Connectivity. This is Kamran Bokhari, your host, with another episode. And this time we’re going to talk about a place that’s kind of like forgotten in the media because there’s just so many crises taking place in the world. It is not easy to keep up with all of them. So naturally things that have been going on for a while, they tend to get the back burner treatment. And here at Eurasian Connectivity and with the help of our friends at Mercy Corps, we try to bring back to life issues that have seemingly been forgotten.

So we’ve had the country director from Mercy Corps of Afghanistan. We just recently had the regional director for Middle East to talk about Gaza. And today my guest is Nicole Hark. She has been the country director for Syria since 2021. Mercy Corps has been doing a lot of work there since 2008, and we don’t often hear about what’s going on in Syria. It’s not like the humanitarian crisis has gone away. In fact, it’s getting worse given the overall strategic environment. So I’m going to pass the mic to my guest Nicole, hi Nicole. Thank you for doing this.

Nicole Hark:

Thank you. Pleasure to be here.

Kamran Bokhari:

So give us a sense of what the current humanitarian situation looks like. I mean, because Syria has dropped out of the news as I was explaining, and especially because of the decline of ISIS. So you rarely hear about what’s really going on, but we can’t forget that the political economic situation is still very dire for the people who are still living there.

Nicole Hark:

No, it’s definitely true and I think in the last five years, unfortunately, as you mentioned, the needs are only increasing. At the moment in 2024, we’re actually seeing the largest number ever of people since the beginning of the crisis expected to require assistance, over 16.7 million people across Syria. There’s recurrent disease outbreaks, particularly of vaccine-preventable illnesses combined with rising incidences of waterborne diseases, a prolonged water crisis, increasing food insecurity and rising malnutrition rates across the country. And it’s really just become increasingly difficult because there is kind of leading Syrians with a sense of a continuing state of emergency, but increasing fatigue or forgetfulness for the Middle East from the wider international community.

Kamran Bokhari:

So I want to sort of follow up on that and tell our listeners what’s life like these days for the common person. Now, obviously it’s a big place. There are dynamics in the east is separate from northeast, is separate from the northwest, and then regime held territories, territories controlled by the Kurds and then down south near the border with Jordan and Israel. So give a sense of, to the extent that you can, about what is the challenge of the average individual living in the country that there’s reconstruction really hasn’t happened and we don’t know when it will happen.

Nicole Hark:

Yeah, so in general, I would say Syrians are getting poorer as the economy continues its freefall. We’ve seen the Syrian pound losing more than half of its value against the US dollar. And because of the political situation on the ground, most Syrians are operating under hyperinflation with a foreign exchange rate either against the US dollar or the Turkish lira and really struggling with kind of the market dynamics of that. What this really means in practice is that the household affordability, regardless of the controlling actor and their linkages to actors outside of Syria, has just plummeted. I would say service delivery is stretched to its weakest point. Reductions in funding since January of this year are impacting millions and further reductions in water provision as expected in the coming months, we’re hearing that roughly a hundred or so health facilities are on the brink of closure due to decreasing funding for the humanitarian situation. And so there’s really just a persistent state of uncertainty for people living inside Syria these days.

Kamran Bokhari:

So you focus on the northeast and the northwest particularly, and we know that there’s this tension between Turkey and the Syrian Kurdish separatist movement that controls a large chunk of territory in the northeast. There are Turkish proxies or groups that are closer to Turkey based out of the northwest, and there is a physical Turkish military presence in Northern Syria in general. So how are you dealing with these different authorities, if you will, non-state and state, and how do you navigate between these various players?

Nicole Hark:

I think first and foremost we try and maintain our neutrality as a humanitarian actor and really position ourselves vis-a-vis whoever the local authority is or in which location it may be that we’re operating to really focus on our need for access, impartial access without any sort of impact or bias or influence on the part of local authorities. And then also in terms of cooperation when it comes to not just access, but also potential resources or conflicts over resources that are arising on the ground. I would say we’ve been fortunate over the course of our time operating in Syria, there are very few obstacles or challenges.

I do think perhaps one small sliver of positive of how many years that this crisis has been operating is that it is now I think more understood on the part of local authorities about what the role of the humanitarian organizations is and what our kind of key principles are. But it maintains a bit of difficulty, particularly when the needs are so high. And there’s always a number of different perspectives on where the limited aid that we have should be distributed, how different individuals, families, communities are selected, and the fact that there is really not supposed to be a role for local authorities or local councils in that process beyond the typical kind of facilitation and access.

Kamran Bokhari:

So on that facilitation and provision of access that you depend on the local actors for, would you say do you face more resistance, less resistance, or is it a mixed bag? Does it depend on what day of the week it is? What are the factors that shape that access that you get over time?

Nicole Hark:

Generally speaking, it’s a bit more consistent than you might expect. I think in terms of the factors, it’s normally an understanding of what we’re doing, what the particular program is and why in terms of why we’ve identified this need in this community and why we are particularly focused on doing it in a particular way, whether it’s service delivery or bringing community groups together. But I think understanding that background and the why is really the primary need. And then otherwise, it’s typically a conversation around making sure that we’re not unnecessarily raising expectations because they also have to manage obviously the pressures and needs coming from the populations that they serve.

And so it is making sure that we’re sort of communicating that we’re not duplicating our efforts and then kind of making sure that it’s clear in terms of what we are and are not capable of delivering in a particular area. But the sort of resistance piece doesn’t really come up very often. And I would say actually one example following that earthquake last year where we actually saw an increased amount of collaboration and coordination with a real understanding of what the humanitarian mandate was, that I think again was a positive benefit because we didn’t necessarily expect that to arise, but we were able to do more and have greater access than we might’ve initially anticipated.

Kamran Bokhari:

At New Lines Institute, we try to look at things geopolitically. And so putting on that lens right now, it seems like at least from what has been happening in the wake of the Gaza war, we’ve seen increased hostility between Israel and Iran. And Syria happens to be a key battle space in which this is playing out. So has this affected your operations? And of course before you answer that, how is that affecting the overall political economic state or is this situation sort of running alongside it and is not having much of an effect?

Nicole Hark:

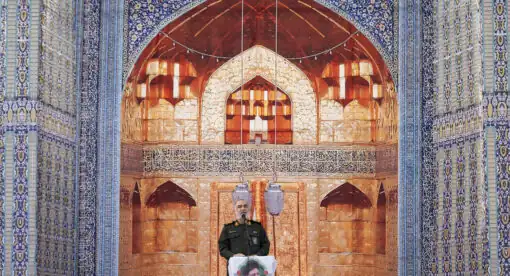

An interesting question, and I think it’s really difficult to say sort of how this will evolve over time. I think it would likely be kind of predicated on the potential intersection between Israel’s targets, right? The Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps, the Hezbollah, and sort of Syria’s commercial interests, right? It’s pretty widely understood looking at Syria that in several sectors, primarily real estate, religious tourism, commodity trade, certain financial mechanisms, Iran and Hezbollah are indeed stakeholders. However, the way in which that manifests or the commercial and economic entities are designed in a way that sort of diffuses the shareholding and the managerial structure and the decision-making in order to ensure continuity. And I think the Syrian government, it appears at least from the outside, that they’ve adopted an approach that helps them to remain somewhat outside of the direct confrontation with Israel. And there seems to be obviously a natural tension between Damascus seeking to move on from being embroiled in the conflict.

It’s obviously newly established kind of linkages with Gulf states on the one hand. And then of course its resistance sort of allies such as Iran and Hezbollah, both of which of course have been supporting the Syrian government for well over a decade. So how long and to what extent they’ll be able to maintain that positioning, I think is still very much uncertain. To your question about the impact to our operations, there’s not as much partially because of course we are focused more on working in the north, so there is not necessarily where we see the strikes happening or predominantly in south central and the government controlled areas. But I think even when there is a concern about potentially heightened insecurity or what that might mean in terms of ripple effects within each area of Syria, it tends to be sort of a day two or three day sort of additional scrutiny or perhaps slight pause in activities or movements depending on what we’re looking at, but not overall disruptive to our broader plans and ability to implement.

Kamran Bokhari:

So we know there are at least 3 million, if not more refugees from Syria in Turkey. Does their presence in Turkey… I’m sure there’s still cross border relationships. Do you see a lot of that happening and is there some assistance coming from north of the border for relief and humanitarian work? Or are you largely and your other partners in the development in humanitarian space, are you the only guys doing that or is there some assistance coming from north of the border?

Nicole Hark:

So there is actually a very robust civil society of Syrian led organizations that are working from Turkey, that are based in Turkey, that are members of the humanitarian community and are very active in the response, particularly in Northwest Syria. Whether they receive funding directly from other refugees who are in Turkey or from the diaspora community more broadly, I don’t know exactly the breakdown there, but they certainly have a very strong presence and I think a very vocal voice in the overall sort of humanitarian policy and advocacy space for all of us working on Syria. And I think that that does help to sort of shed light on the needs. It certainly helps in terms of that assistance and the connections with communities. It is a relatively open border in terms of humanitarian assistance for crossing as well as for staff members going into the communities where we work. And I think that is certainly helped by a number of people who have those connections and those ties. But certainly there are obviously other refugees in other parts of Turkey that are not necessarily connected with the humanitarian response specifically.

Kamran Bokhari:

So is that open border situation just limited to Northwest Syria or is there some ability, some similar situation in the northeast controlled by the Syrian Democratic Forces, the SDF, led by the Syrian Kurdish movement?

Nicole Hark:

So no, the border crossings and the facilitation that you see in Turkey is not the same situation for northeast. There is a kind of typical market relationship for getting goods across Syria, and there are humanitarian actors that are able to cross as well as some Syrians between Iraq and Syria. It is not quite in the same way, whereas in Turkey where you do have more of the presence with the United Nations, the facilitation of aid and sort of trans-shipment services with the United Nations role for the northwest, that is not the same in northeast.

Kamran Bokhari:

So switching back to the northwest, we in the west from time to time, we won’t get a whole lot of information and we’re grateful for you to come on and provide us with this granular detail that we don’t get to hear about, at least not that often. But we do hear about this group called Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, which is the Sunni radical group that according to reports, controls a large part of Idlib province. And recently they’ve been in the news because they’ve been public protests against their authority in that area. What can you tell us about the situation there in the province of Idlib?

Nicole Hark:

Yeah, so I think HTS’s approach in recent years has been sort of one of attempted pragmatism, but I think there’s really a lot of array of factors that have really stretched this approach quite thin. And perhaps what we’re seeing now is it’s been stretched to its limits. I think while some communities and their stakeholders seek a more inclusive participatory, and I would say relatively less religiously oriented means of governance and policy, there are others within Idlib who desire a more authoritative, perhaps heavy-handed or theocratically underpinned sort of way of life. And this is a tension point that’s starting to bubble up more to the surface. I think that pragmatism has also placed leadership in Northwest Syria in a tough position between sort of their hard-line opposition activists and those who interpret the current context as untenable, whether related to trade services or broader stability, particularly vis-a-vis the government of Syria. But what has ultimately sort of manifested over the past several months in terms of protests is a reflection of the extent of pragmatism. In some circumstances, HTS’s leadership seems willing to reform, but posturing maybe in others.

Kamran Bokhari:

Well, thank you for those details. So if I may continue on that same train of thought, and you can take this to the northeast as well. We don’t hear a whole lot of reports about violence in the recent past. I would say occasionally we’ll hear about ISIS and whatnot, but by and large, from the outside, it appears that violence in Northern Syria, both the west and the east has kind of died down. To what extent is that true and what are the challenges? Because when it’s violent, then there’s a different dynamic and people are just trying to survive the violence, but when violence subsides the other needs of people come to the fore. So could you shed light on that please?

Nicole Hark:

So you’re correct. I think the reports of violence are definitely decreased, and that is based on the reality on the ground. It’s certainly not gone away, but I think we’ve had relatively stable front lines in terms of active conflict between the different local authorities in each location. And while there continue to be airstrikes in northeast from the Turkish perspective or attacks between the government of Syria or HTS or other groups in the northwest, those are still relatively few and far between over the course of a year. And so we have not necessarily seen quite the level of civilian casualty, particularly on a larger scale. It tends to be more isolated incidents and also very infrastructure focused and less human targets in that sense. I think as you mentioned, what that does mean is that then the overall crisis has reached a level of protracted stagnation that is incredibly challenging for the local population, the basic needs of food, water, healthcare, income generation.

We’re seeing increased incidences of child labor, more early marriage as a way of trying to cope sort of with the challenge of supporting larger families and of course a continuing fracturing of the social fabric. So I think unfortunately while the violence may have stopped or reduced in certain areas, the fact that there has not been much tangible progress on an actual political solution has led to a relative situation of persistent challenge without much light at the end of the tunnel or future hope of how people are able to recover from what has been kind of just a persistent conflict to date.

Kamran Bokhari:

So considering that a political settlement, and it’s difficult to talk about it in Syria as a whole at the national level, but even in different pockets of the country and different areas as you well know, have their own dynamics. In the absence of that, what are you guys thinking at Mercy Corps in terms of your future operations say over the next several years? I mean, I guess in some ways you’ve already adapted to this sort of, well, there is no settlement, but there is no actual conflict either. It’s somewhere in between. So could you share what are your future plans? I’m sure you guys are forecasting on your own in terms of how you’re going to adapt to potential change in the ground circumstances.

Nicole Hark:

Yeah, I think at the moment from a programming perspective, it becomes really a conversation of what can we do that is somehow more sustainable in the sort of short to medium term, but does not necessarily sort of violate the sanctions and the guidance under the UN Security Council resolutions in terms of longer term reconstruction or recovery. And so we’re really trying to focus on, A, just meeting those immediate needs of course, but really kind of how do we meet those needs in a way that hopefully addresses them in a longer term perspective. So for example, instead of water trucking and the provision of water and hygiene services on a daily service delivery perspective, can we actually work to create water stations in an IDP camp, for example. And work with the community members to help train them on how to operate and maintain that system so that it has a more lasting usable life?

When we talk about energy access and much of the infrastructure around energy being destroyed, most recently from the Turkish airstrikes in northeast, we look at are there efforts that can be made on solarization. And can we actually bolster the level of knowledge and training for Syrians inside the northeast in terms of repairing those systems, installing those systems and maintaining them in the longer term so that they are not necessarily as reliant on the grid going forward. And actually then have members of the community who can take care of those systems in long-term and of course identify a way for them to earn an income as well. So it’s trying to navigate the challenge that we’re not really able to do traditional development work based on the political red lines, and at the same time, we can’t keep treating it as an emergency response because we’ve just far surpassed the natural timeframe under which you might expect persistent humanitarian assistance. And so really trying to think creatively about what’s possible with the resources on the ground. And I think the people in particular are really eager for that same kind of solutions oriented mindset.

Kamran Bokhari:

So you mentioned the sanctions regime, and that sort of takes me to my next question, which is that in recent years we’ve seen efforts by major Arab states to try and re-establish relations with the Assad regime. How is that dynamic, if it is at all, helping with the financial assistance so that humanitarian work can be expanded or can be improved because you’re limited by the sanctions? So is that diplomacy having an effect just yet or no?

Nicole Hark:

In general, I would say no. The normalization by the Arab League in the last year has had little to no impact on the ground. I think at kind of the macro level, the priorities have been loosely agreed upon. The sequencing of these priorities, however, it has not. And so for example, the regional actors I think continue to be highly concerned with the narcotics trade stemming from Syria and coming into some of those borders. But the priority from Damascus on the other hand, is really about finding partners who will lobby for sanctions relief. And really the starting point for those has yet to be determined. And so I think while trade has been formally re-established between Syria and certain Gulf states, for instance, special regulations, again largely related to narcotics smuggling, and of course high costs have really been the obstacles. Not to mention of course, that the pressure the US is likely placing on its regional allies to make sure that there is still adherence to those sanctions.

Kamran Bokhari:

Speaking of financial assistance, we know in years past the Syrian regime has been a recipient of a considerable amount of assistance from Russia and Iran. But with Russia tied up with the Ukraine war now two and a half years on, are you seeing some sort of a, if you will, buckling under the pressure on the part of the regime, is it hurting more? And what is that doing in terms of expanding the humanitarian crisis? You already mentioned that service delivery is declining over time on the part of Damascus and its various local authorities in different regions. So does that add to the overall workload, if you will, of Mercy Corps and the broader ecosystem of humanitarian and development actors?

Nicole Hark:

That’s a good question. Unfortunately, given that Mercy Corps does not work in the government controlled areas, it’s difficult for me to speculate specifically on the current situation there. I think based on the work that our research team does, and certainly in discussion with some of my peers from other organizations who do work from Damascus, I feel I would say that the Russian involvement in the Syrian political economy still exists, right? Russian commercial and industrial stakeholders continue to invest, establish companies and capture a pretty significant piece of the Syrian commodity trade. But I think the conditions that surround Syria however impede on these investments. So I think the Syrian government and its kind of political economic control finds itself between attempting to reintegrate with western dominated global structures, but also committing to alternative structures being promoted by Russia and China. And I think the former has largely been unsuccessful and is highly unlikely to take place soon considering the UN Security Council resolutions and the current government stance.

However, this would theoretically enable a faster paced and more impactful recovery and development. I think the latter is more politically palatable for Damascus, but this broader kind of alternative system remains in its infancy or largely theoretical. At this point, there’s obviously been lots of engagement with China to supplement or potentially supplant sort of the Moscow support, but I think there’s maybe a bit of an open question yet to be seen whether and how those sorts of conversations are really utilized for investment on a larger scale. On the side of the kind of north, and I think particularly because of the differences in terms of political support and the ties to different countries, it is definitely different for northeast and northwest compared to the government controlled area.

Kamran Bokhari:

So you mentioned the IRGC earlier and in the light of this sort of uncertainty, and it could go either way, there’s nothing saying that war will inevitably break out between Hezbollah and Israel in which there’s a great fear that it’ll expand into Syria and perhaps even into Iraq. And that already seen the Iranians directly drawn into a conflict with Israel, albeit it was very limited exchange. But how do you see from your vantage point? And you mentioned you have researchers, what are they seeing in terms of the Iranians and their movements that could increase the risks of this conflict and then you have a potentially bigger humanitarian crisis, or are they being careful as some segments of the media is reporting?

Nicole Hark:

I think so far, at least from the perspective that we’re looking at and what we’ve been tracking, it actually has not come up as much in terms of either the Iranian influence or the potential of them as the disruptor. I think from the conversations that we’ve been having with our counterparts who are based in Beirut, the rhetoric at least, and certainly the messaging from Hezbollah side has really focused on Gaza and on the ceasefire and not necessarily trying to continue to escalate or initiate a separate conflict with Israel. And I think that’s been sort of the continuous message over the last several months. And where we see this tit-for-tat between the two sides tends to be driven based on what the situation or the dynamics are in Gaza or with the ceasefire conversations happening at the same time.

It’s difficult to say of course, because many of these things are sort of opaque or deliberately big, but at least so far from the things that we’re tracking at our neighboring countries and what the regional dynamics look like, we really don’t see as much of the Iranian influence in the typical posturing and positioning coming out of Lebanon.

Kamran Bokhari:

So it’s been an election year for the United States and at least two of its major allies in Europe, both the United Kingdom and France, and these are key players in what we know as the international community and their ability to mobilize resources for humanitarian purposes. And with an expected change or expected potential change in Washington come November 5th, two questions. So what are you looking at in terms of how that’s going to affect your work in Syria and if it’s not already affecting it, and two, what do you think Washington should be doing to help out with your work in Syria? Because God knows it’s a huge Herculean task that you guys and the broader ecosystem of development and humanitarian actors cannot do on their own, and there’s definitely limitation of resources, financial and material, otherwise.

Nicole Hark:

Definitely. I think at the moment in terms of what we’re looking at and how a shift in the administration would affect our work, it’s really tied to the ongoing conversations between the US forces and the Iraqi government around US troop presence and what a shift or a change in that presence in Iraq would mean for the presence in Northeast Syria and the coalition forces. And of course the coalition is bigger than the United States. You obviously mentioned the UK and France, and I know they’re obviously very closely conversation with the US as well to understand what, if any change there may be. At this point, we haven’t been able to get a firm understanding of what that might look like, but it’s definitely something that in terms of things we’re looking ahead to what we might try and plan for at least prepare contingency plans for.

There would definitely be a change in the dynamics on the ground if there were a change in the presence of the coalition forces, and I think that would then have an impact in terms of the work in Northeast Syria. And overall, again, that question of where are the current status quo and how things may evolve between the different political actors. I think also the level of attention for Syria or the willingness to kind of revisit policy decisions around Syria, we do sort of consistently hear questions related to the presence of ISIS in the country. It is obviously something that is tracked quite closely, but also more broadly in terms of some of those other driving forces around the economic deterioration and the overall sort of desperation of the crisis and what that might mean in terms of future instability in the region. In terms of what the US can do to help really, I mean obviously the number one, which you mentioned is just increased funding.

We’re dealing with sort of recent cuts from US funding for Syria in the last year. So a reversal of those cuts were really seeking more sustainable investments to shift away from that kind of stopgap humanitarian assistance. It’s been a difficult conversation, not just for Syria of course, but I think more broadly in terms of overseas assistance. The continued support for the UN Security Council Resolution 2254, that real emphasis on a political solution so that we can get to more meaningful engagement and really try and give support and advice to our regional allies in pursuit of meaningful political reforms. And then I think more broadly, just to hold both ourselves and others accountable for their actions in Syria and in the region in order to demonstrate sort of a really solid commitment to upholding humanitarian principles, reducing targeting of civilians or civilian infrastructure that we’ve seen particularly in the last year has had a pretty dramatic impact to the situation of everyday life for Syrians.

Kamran Bokhari:

Well, before we wrap up, Nicole, I want to give you another opportunity to touch upon anything that we have missed in this conversation that you, from your perspective as the country director for Mercy Corps, think that it is essential and that people should know about the work that you are doing and the situation inside Syria.

Nicole Hark:

I think maybe I’ll just close with an anecdote. I was recently with my team in northeast and I had one of my team members ask me whether Americans understand how much their elections impact the day-to-day lives of Syrians. And I felt really bad because in essence, I knew that the answer was no, not really. And at the same time, it was very interesting the level and the depth of conversation that we were able to have about how decisions are made within the United States, how policy in the Middle East impacts so much of the situation on the ground, not just from humanitarian needs, but also the broader geopolitical dynamics. And I think it’s really striking just how closely my team and their families are following what’s happening globally because they recognize just the ripple effects that it will have and the impact and what it will mean for their sense of day-to-day security and overall stability. And also potentially a hopefully brighter future in which they can remain in Syria and provide more for their families and have a better life.

Kamran Bokhari:

Nicole, thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me and to enlighten our listeners about the situation in Syria and the challenges that you face and the challenges the international community faces moving forward. Folks, that was Nicole Hark from Mercy Corps. She’s the group’s country director in Syria, and you have been listening to another episode of Eurasian Connectivity with Kamran Bokhari signing off for now, and I hope to see you soon. Thank you.