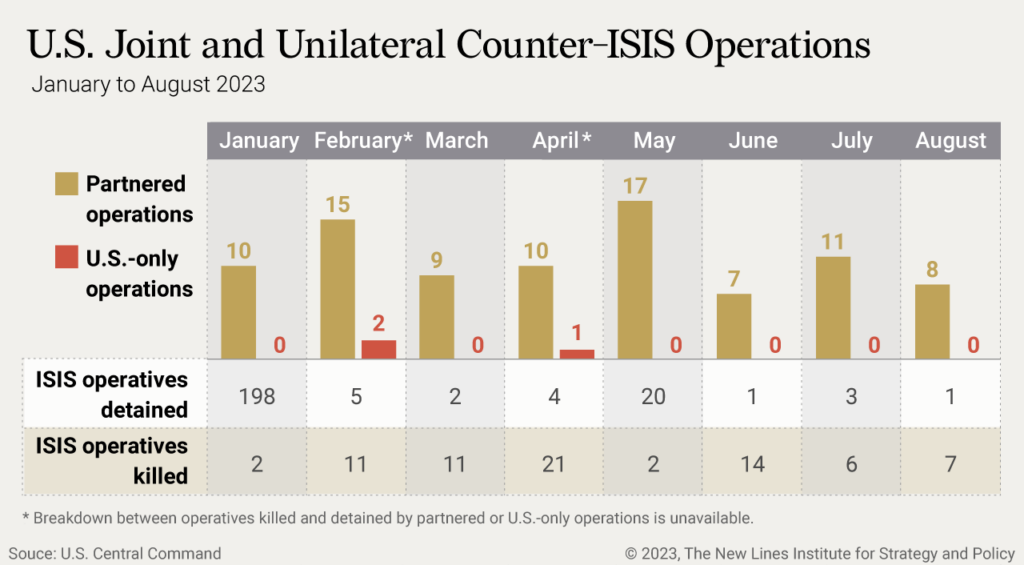

The continual success of the U.S.-led Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR) campaign to limit the operational capacity of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) rests on local Syrian and Iraqi partners. These groups, with the training and advising support of the U.S.-led Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS, also play a key role in fulfilling America’s regional objectives, such as limiting Iranian influence. The U.S. remains under both external and internal pressure to remove its forces from the side of the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in Syria. All the conflict’s powerbrokers, including the Assad regime, Russia, Turkey, and Iran, have strategically taken steps for years to push the U.S. out of Syria – for example, Iranian-aligned militias attacking U.S. forces, Turkish airstrikes on Kurdish commanders accompanied by U.S. troops, and Russian fighter jets and armored trucks behaving aggressively toward U.S. planes and convoys. U.S. Rep. Matt Gaetz’s March 2023 bill to force the removal of U.S. forces from Syria failed in the House by a 3-1 margin, but this move highlights the growing inclination among U.S. policymakers to refocus U.S. time, energy, and resources elsewhere. This policy reprioritization may also play a role in the upcoming 2024 U.S. elections as Republican front-runners attempt to draw favor with a base that increasingly supports an isolationist foreign policy.

With a withdrawal of U.S. forces from Syria (as well as Iraq) becoming more likely, U.S. policymakers must understand the long-term effects withdrawal will cause and then adapt accordingly. This is particularly urgent given the possibility of a U.S. withdrawal triggering malign actors in Syria, including Iran, to rush to fill the power vacuum. The hastily executed U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021 exposed the dangers that local interpreters, translators, civic leaders, and government contractors can face when American troops leave. The U.S. has previously utilized a variety of immigration programs to enable Afghans and Iraqis who worked with the U.S. government in its occupation of those countries to come to America; however, these programs have not been expanded to account for OIR partners in Syria.

U.S. officials must begin to develop policies and program infrastructure now to secure the safety of U.S. partners in Syria in a way that the U.S. fell short of doing during and after its withdrawal from Afghanistan. A comprehensive visa program will create a more deliberate pathway for critical Syrian OIR partners to immigrate to the U.S. prior to an eventual withdrawal. The previous 117th House of Representatives drafted model legislation, called the Syrian Partner Protection Act, that would have provided Syrians who assisted the U.S. in its activities against ISIS after Jan. 1, 2014, with special immigration status – therefore making Syrians eligible for a green card and the potential for eventual citizenship. While the bill did not emerge from committee in the previous House, passing a similar version of this bill now, with additions to account for lessons learned from Afghanistan, is imperative to long-term U.S. interests in the region and America’s reputation among partners and allies.

Current State of Play

Since the physical defeat of ISIS in March 2019, the northern and eastern regions of Syria have been a crossroads for regional military actors as well as terrorist groups. Many of the players, including Iran, the Assad regime, and Turkey, want the U.S. to abandon its support of the SDF, but the American presence remains. The U.S.-SDF partnership has moderately stabilized the provinces of Hasakah and Deir ez-Zor, despite less notable clashes and “tit for tat” fighting on the edges of opposing actors’ zones of control.

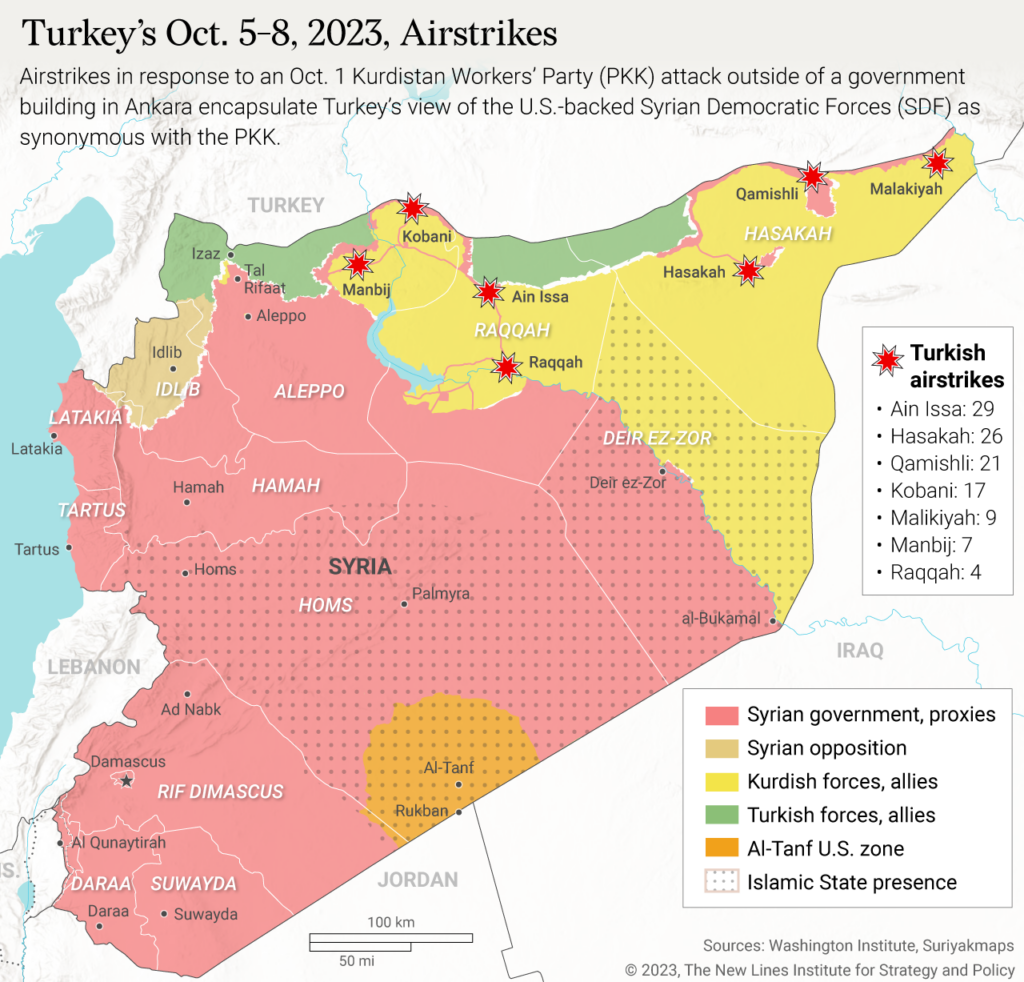

While it’s doubtful that ISIS can develop the capacity to control territory to the magnitude it did in 2014, the U.S. actively engages “by, with, and through” its ally the SDF to maintain watch over the 10,000 ISIS members currently locked in prisons in eastern Syria. U.S. support for the SDF also serves as a stopgap to Turkey launching an aggressive campaign to completely dismantle all Kurdish groups active along its border, which the Turkish government considers to be terrorist organizations. Former U.S. President Donald Trump’s abrupt 2019 decision to withdraw and reposition U.S. troops stationed alongside the Syrian-Turkish border directly enabled a Turkish operation that targeted the SDF and the People’s Defense Units. Trump’s move seems to have been due to both the claim that ISIS had been defeated earlier that year and the desire for the U.S. not to be dragged into the impending Turkish-backed offensive.

Turkey’s concerns regarding U.S. support for the SDF also reflect Turkey’s relationship with the Assad regime. As multiple Arab countries look toward normalization with Damascus, Assad’s starting point with Turkey is ending the occupation of pockets of northern Syria by Turkish forces and proxies, a violation of Syrian sovereignty. Turkey remains caught in the middle, as normalization with the regime would potentially allow Turkey to repatriate some of the 3.5 million Syrian refugees currently living in Turkey, despite uncertainty over the legality of such a move due to safety concerns. Finally, Turkey’s ongoing hostilities toward Kurdish groups have spilled over into its hesitation around NATO membership for Sweden.

The major geo-strategic actions of Assad depend on Iran, Russia, Turkey, and the U.S., and vice versa. Unless a major actor changes the dynamics of their involvement in Syria, a stalemate can be anticipated. That said, the SDF losing U.S. physical support in the East could have massive ramifications for the conflict and U.S. regional interests.

The Eventual Withdrawal of U.S. Forces From Syria

U.S. President Joe Biden’s administration’s chaotic withdrawal from Afghanistan in August 2021 seriously damaged U.S. credibility. It will be important for the U.S.’s reputation on the world stage to be able to successfully withdraw from Syria (and Iraq) without creating the security and political vacuum that occurred in Afghanistan. Today, approximately 1,000 U.S. troops are in Syria. Another 2,500 are in Iraq, with a total of 7,800 U.S. contractors in both. The ability of the U.S. to perform such a critical advising and training function, despite its small number of troops, speaks to the level of support local translators, security forces, and businesspeople provide. The U.S.’s departure from select bases in Iraq and Syria between 2019-2020 should serve as an example for U.S. policymakers to begin laying the groundwork for an eventual complete withdrawal from Syria.

An unsupported and unstructured withdrawal would likely precipitate a massive geopolitical nightmare in Syria, particularly given the risk of Iranian-aligned militias filling security and political gaps, as they did in Iraq in 2020. When U.S. forces stationed in Iraq’s Anbar and Erbil provinces faced theater ballistic missile strikes launched by the Iranian military’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps in January 2020, the U.S. military made the call to withdraw U.S. forces and Coalition troops from eight of the bases in western and northern Iraq, as these forces were not actively fighting ISIS. Although the drawdown process in Iraq wasn’t done to purposefully cede power to Iran-backed militias, U.S. withdrawals from select bases in the spring and summer of 2020 happened to be in areas where Popular Mobilization Forces had a high degree of influence on politics and security, such as al-Qaim. Thus, the U.S.’s departure from Iraq simultaneously bolstered Iraq’s sovereignty and tacitly benefited Iran. Iranian-linked militia attacks on multiple bases housing U.S. troops in Syria and Iraq in October 2023 illustrate Iran’s continued willingness to violently expel U.S. forces from the region. This current period of renewed Iranian aggression forces U.S. policymakers to further consider withdrawal options.

Iran has interwoven itself into the Syrian conflict by presenting itself and its Axis of Resistance as an additional security guarantor and profit generator for the Syrian regime. Potential scenarios of what could follow a U.S. withdrawal present a plethora of opportunities for Iran to expand its influence based on how the other actors react. Given Turkey’s actions following Trump’s decision to withdraw U.S. troops from northern Syria in 2019, it is clear that Turkey is willing to launch an anti-Kurdish offensive given the slightest window. In October 2023, Turkey conducted around 580 airstrikes and artillery attacks on military sites and civilian infrastructure in north and east Syria. Also in October, Turkey’s Parliament extended the mandate for Turkey’s cross-border operations in Iraq and Syria for three more years. Knowing this, the SDF would likely make a deal with Assad and Russia to delay an incoming Turkish invasion in exchange for the regime having more latitude to reclaim land in eastern Syria; the SDF used a similar calculus in 2019. The Iranian-aligned militias already active in the East, such as in Deir ez-Zor, would likely be part of a regime-backed offensive. These groups have operational experience in the East that could be a force multiplier for the regime.

ISIS has often looked toward slips in the SDF’s capacity, such as during recent periods of SDF-tribal clashes, as an opportunity to resurge. This hypothetical scenario shows how one actor’s movements act as a domino for every other stakeholder in Syria. In the aftermath of a U.S. withdrawal, the risk is high of actors connected to Iran and/or Turkey gaining power in Syria, all of whom, along with the Syrian regime, are likely to target persons who had previously supported U.S. activities.

Even with these potential ramifications in mind, segments of both U.S. policymakers and the public are increasingly favoring withdrawing U.S. forces from Syria. Former President Barack Obama’s administration’s pivot to Asia and European reassurance has been followed by similar trajectories in the Trump and Biden administrations, thus speaking to a trend that is expected to continue for the foreseeable future. Simultaneously, however, members of Congress, particularly in the Republican party, have been turning toward withdrawing U.S. forces from the region. In March, U.S. Rep. Matt Gaetz presented a concurrent resolution to withdraw all U.S. forces from Syria on the premise that “Congress never authorized work in Syria” and that the U.S. is endangering its forces when it is not “in a war with or against Syria.” This resolution failed in the House by a vote of 321-103, but even this number of “yea” votes is notable given the effects that this withdrawal would have on the ground.

U.S. policymakers are mirroring the growing proportion of the Republican base who favor reducing America’s military commitments abroad. Most foreign policy-related statements made in the first 2023 Republican presidential debate, for instance, revolved around combating the threats that actors pose directly to the American homeland rather than to other countries, such as when technology entrepreneur Vivek Ramaswamy argued for reallocating funding currently spent on Ukraine for the U.S. southern border. Another Republican presidential candidate, current Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, has opposed military intervention in Syria from the start; he made headlines in 2013 as a congressional representative for differing from most of his Republican colleagues at the time by opposing Obama’s decision on the matter.

Even if Biden wins a second term, the war fatigue of the American people is only increasing and pressure will likely continue to mount for a withdrawal from Syria. It remains to be seen how the Israel-Hamas war and its regional ramifications will affect how U.S. policymakers view ongoing troop presence in Syria. It is thus vital that the U.S. start to prepare immediately for a responsible withdrawal from Syria, including providing options for visa access for Syrians who worked side by side with U.S. troops.

Current Immigration Infrastructure

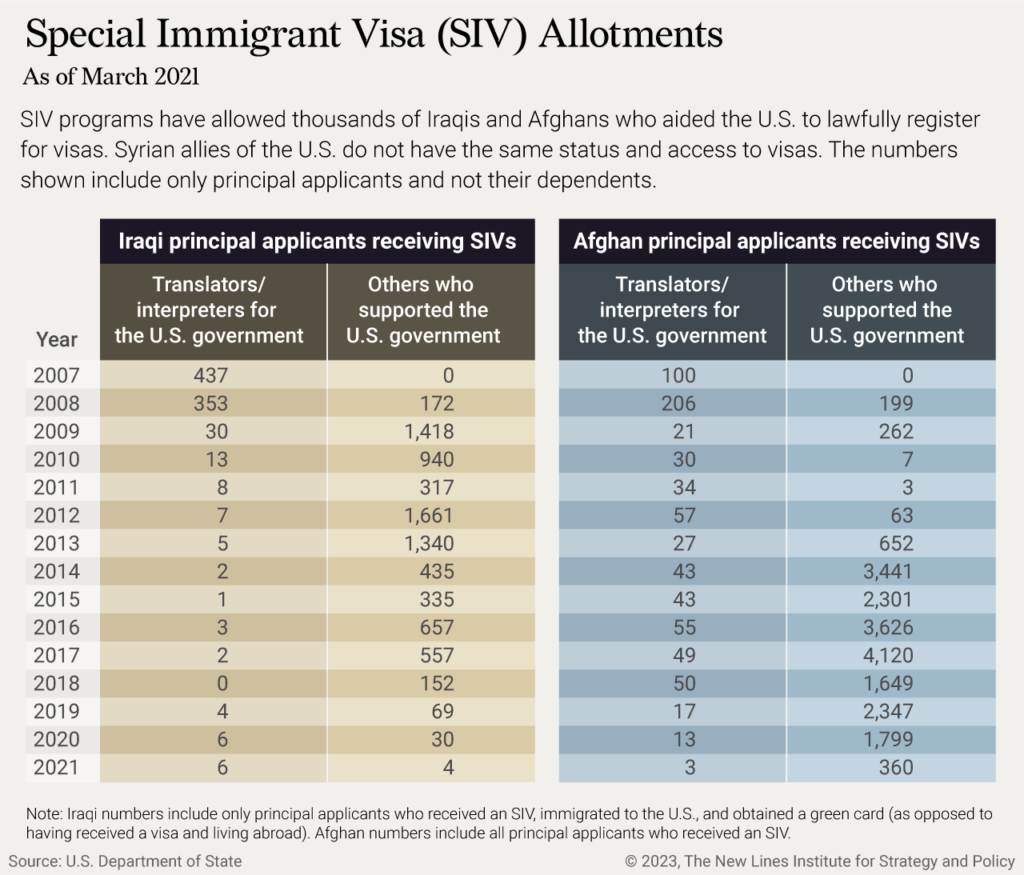

The U.S. has a precedent for providing pathways to immigration for translators, interpreters, and/or contractors from Afghanistan and Iraq who aided the U.S.; the most common U.S. visa among this group is the Special Immigrant Visa (SIV). To qualify for a SIV, applicants must have been employed “by, with, or through” the U.S. government or NATO’s International Security Assistance Force (in Afghanistan’s case) for over a year, plus applicants need a recommendation from a supervisor and proof of experiencing an ongoing threat in their home country due to their past or current employment.

With the understanding that Afghans who had supported U.S. efforts would be targeted with retaliatory violence once the U.S. military left Afghanistan, the Biden administration granted P-2 (Priority 2) status to qualifying Afghans and their families in August 2021. P-2 status provides Afghans who wouldn’t have previously qualified for the SIV access to the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program, which refers refugees for the pathway to permanent resettlement in the U.S. Those with expanded access include those who worked with U.S.-funded institutions and those who worked for U.S.-based nonprofits or media organizations, thus emphasizing the importance of offering this assistance to Afghans with less-direct ties to the U.S. military as well. The U.S. government assessed the threat to Afghans connected to the U.S. and created easier pathways to emigration, though in the case of Afghanistan this happened as the Biden administration scrambled to withdraw U.S. forces. This same logic must be applied to the eventual withdrawal of U.S. forces from Syria, only this planning needs to begin sooner rather than later.

In 2006, a unique type of SIV was also created specifically for Afghan and Iraqi translators/interpreters, which allotted 50 visas per year for applicants from these two countries combined. The U.S. temporarily increased the number of visas for Iraqi translators and interpreters in 2007 and 2008, likely to entice Iraqis to volunteer for these positions amidst the surge of U.S. forces deployed to diminish sectarian violence in Iraq. Qualifying standards are stringent, as Iraqi or Afghan nationals are required to have been a translator or interpreter for U.S. forces or the U.S. Embassy for at least 12 months and to get a letter of recommendation from either the embassy’s chief of mission or the general or flag officer of the unit they worked with most directly.

Multiple U.S. administrations have displayed a willingness to adapt resettlement programs for those living in conflict zones – such as through raising the cap for Iraqi translators/interpreters in 2007-2008 or granting Afghan nationals the P-2 designation in 2021 – and it is now time for policymakers to extend this safeguard to Syrian partners. Yet this adaptation needs to happen more efficiently than in the past – before the U.S. finds itself in a crisis scenario. A withdrawal from Syria will cause massive geopolitical ramifications. When a decision is made to withdraw from a country, it is common for policymakers to focus only on getting Americans out safely – for example, the Trump administration’s acceptance of a three-month deadline to withdraw all U.S. troops from Afghanistan with the February 2020 Doha Agreement. However, this marked the beginning of the end for ensuring the safety of those Afghans who had collaborated with U.S. troops for two decades. Washington decision makers must learn from the past and plan for all contingencies when it comes to withdrawing from Syria – including how to keep that withdrawal orderly.

The Way Forward for Syrian and Iraqi OIR Partners

U.S. policymakers must account for the Syrians who have supported OIR through the expansion of the Special Immigrant Visa program to include these Syrians. While not only demonstrating the goodwill and commitment of the U.S. to the local forces it has worked “by, with, and through” to counter ISIS since 2014, potential resettlement is a valid recruitment tactic in an increasingly dangerous kinetic environment. The SDF depends on the U.S., and the translators/interpreters who support this partnership, to maintain power and territorial control in northeastern Syria. Recruiting Syrians with linguistic and cultural skills is a priority for national security; Syrians with critical skillsets can even be utilized within the U.S. military. Furthermore, the Biden administration’s jumbled handling of the logistics in the Afghanistan withdrawal, such as with the departure of U.S. private contractors without notice, diminished the U.S.’s credibility globally. The U.S. prioritizing figuring out the details of a visa program ahead of any major withdrawal decisions will help restore some of this lost credibility.

Model legislation already exists. The 117th House of Representatives introduced a bill called the Syrian Partner Protection Act (SPPA) mid 2022 that was designed to expand the SIV program for Syrians who “assisted U.S. efforts in Syria against the Islamic State.” This is the most current version of a bill that has been proposed in multiple sessions of Congress. The bill specified that 4,000 Syrians who have documented proof of working with the U.S. on or after early 2014 would be given a U.S. visa annually for five years following passage of the bill. This bill delineated the rationale behind the program and clearly laid the groundwork for some, but not all, of the program’s implementation.

Although the SPPA remained in committee, its bipartisan sponsorship reflects the possibility that a renewed legislative push could prove more successful in generating discussion and progress around this effort. It is unknown how a bill such as this would move through a Republican-led House given the demographic shifts discussed previously; however, both parties supported not stranding Afghan allies on the battlefield during America’s withdrawal from Afghanistan. The upcoming 2024 U.S. presidential election could compel candidates from all parties to appease voters by declaring Syria withdrawal intentions. It is critical that U.S. lawmakers pay particular attention to this issue during the next year.

The SPPA’s language qualifies Syrians who served as an “interpreter, translator, intelligence analyst, or in another sensitive and trusted capacity,” but does not mention those in less formalized positions. The P-2 designation for Afghans expanded the group of qualifying individuals to include those who were employed at institutions funded by the U.S., U.S.-based media organizations, and/or U.S.-based nonprofits. A similar allowance for Syrian applicants, plus inclusion of civic leaders and local government contractors, would better attract these critical individuals to aid U.S. forces.

By the conclusion of the Afghan SIV program in December 2024, a total of 38,500 Afghan nationals who aided the U.S. during its occupation, plus their immediate family members, will have been resettled in the U.S. under the visa. This amounts to about 2,000 Afghans per year of U.S. occupation. (This figure excludes the thousands of Afghans who were evacuated through informal channels during and immediately following the U.S. withdrawal). Regardless of the 4,000 Syrians per year quota the SPPA currently suggests, the policy should be critically examined often to determine if it is flexible enough to include other qualifying nationals. Alongside the inspector general’s annual report to select congressional committees on the implementation of this SIV program, the inspector general should also present to these committees an evaluation of the Afghan and Iraqi SIV programs and their implementation. This mechanism will allow U.S. policymakers to update the language and details of existing SIV programs while continually using lessons learned to improve the resettlement experiences of trusted U.S. partners.

The Syrian Democratic Forces remain essential for America’s success in Syria; America, likewise, is essential for SDF survival. Still, sentiments in the U.S. suggest that a U.S. withdrawal from Syria may happen sooner rather than later – making it important to prepare now for the aftermath of this withdrawal. U.S. policymakers must plan for immigration infrastructure for Syrian partners so that an unprepared, dangerous withdrawal of U.S. forces does not occur in Syria, as it did in Afghanistan. The U.S.’s global reputation, especially in the Middle East, depends on it.

Myles B. Caggins III is a retired U.S. Army colonel. He provides expertise on public information warfare, ISIS, Kurdish affairs, veterans issues, national security, and military culture. He served three year-long combat tours in Iraq. He is former spokesman for the Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS in Iraq and Syria. Colonel Caggins earned numerous military awards, and decorations, including, the Combat Action Badge, and the Presidential Service Badge. He is founder and CEO of Words Warriors LLC a translation, public relations, and business advising company with offices in New York City and Erbil, Iraq. He is a life member in the Council on Foreign Relations. On social media @mylescaggins

Carolyn Moorman is an Analyst and Content Coordinator at the New Lines Institute. Her research focuses on non-state actors in the Middle East and West/Central Africa. She also produces the Institute’s Contours podcast. Previously, Carolyn conducted research at the American Enterprise Institute’s Critical Threats Project and the Institute for the Study of War. She previously assisted Dr. Nathan French with research in Miami University’s Department of Comparative Religion and interned at the Heritage Foundation and the U.S. Embassy of Luxembourg. She tweets at @Carolyn_Moorman

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of the New Lines Institute.

Editor’s Note: This piece initially contained an error that has been corrected regarding the number of U.S. troops in Iraq. (Feb. 7, 2024)