Turkey’s Syrian refugee population has emerged as a political flashpoint in the country’s upcoming elections, with leading candidates competing to offer the most aggressive proposal to deport the refugees back to Syria. Although the plans vary in substance, they share a disregard for international law – and Turkey’s existing refugee agreements with the European Union – that threatens to further strain Ankara’s relationships with both Brussels and Washington. President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s administration has forcibly deported hundreds of Syrian refugees since late 2022, while his primary challenger, Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, has vowed to send all Syrian refugees back to their country of origin in under two years, regardless of circumstances in Syria.

Forcible repatriation of refugees to countries where they have a credible fear of harm is a violation of Turkey’s obligations as a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention, and the move threatens to upend the basis of Turkey’s 2015 deal with the EU to limit refugee flows into Europe. The United States and the EU cannot solve this problem on their own, but they do have an opportunity to prevent this situation from turning into a larger crisis, using their economic and diplomatic leverage to pressure Ankara against future deportations while working with the Turkish government to meet the financial challenge of supporting the largest registered refugee population in the world. As the United States turns its attention toward competition with Russia and China, it should remain aware that the long-term care of millions of Syrian refugees who do not want to return to their country will be a challenge for the region that could metastasize and jeopardize the stability of U.S. allies and partners neighboring Syria.

Dwindling Prospects for Voluntary Return

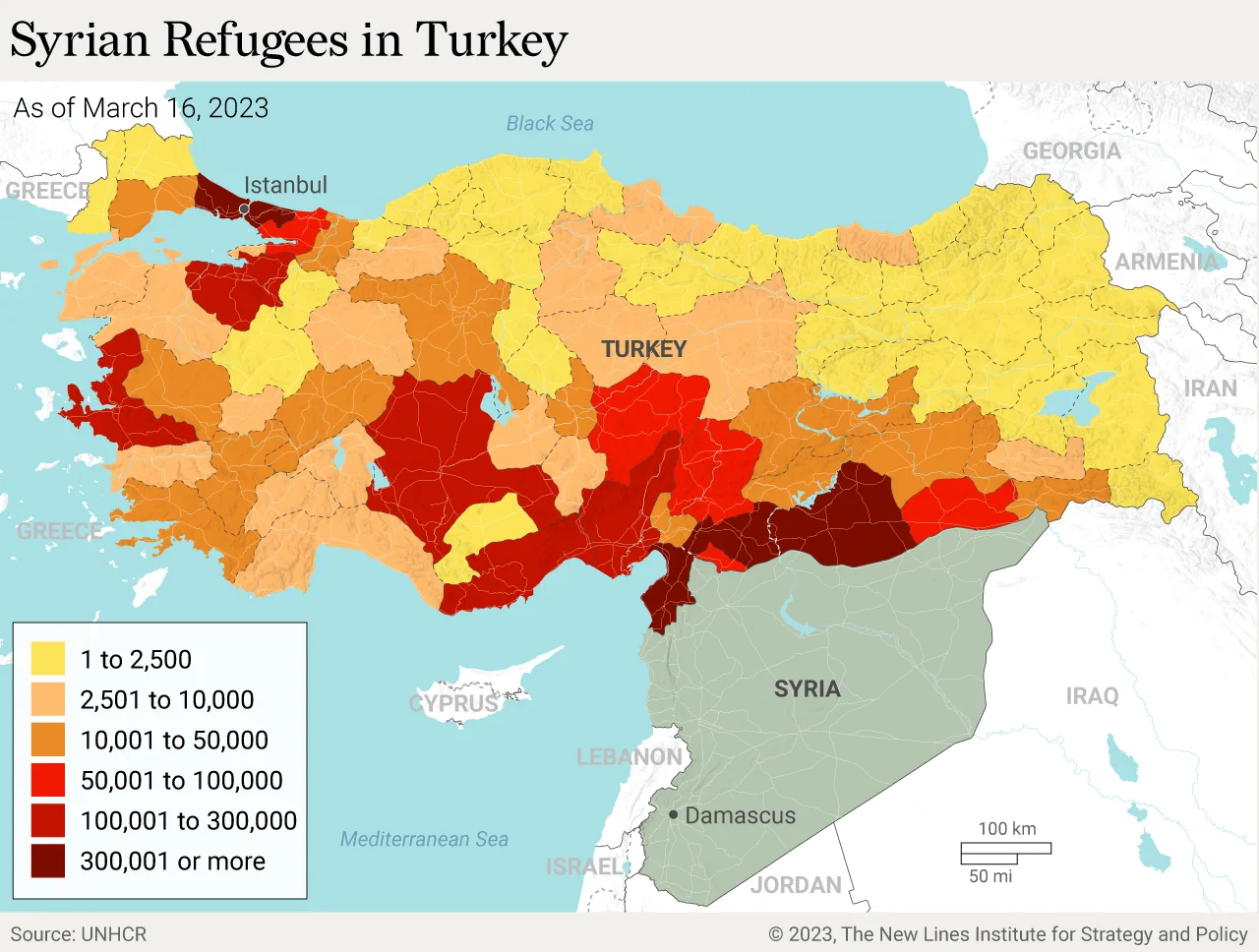

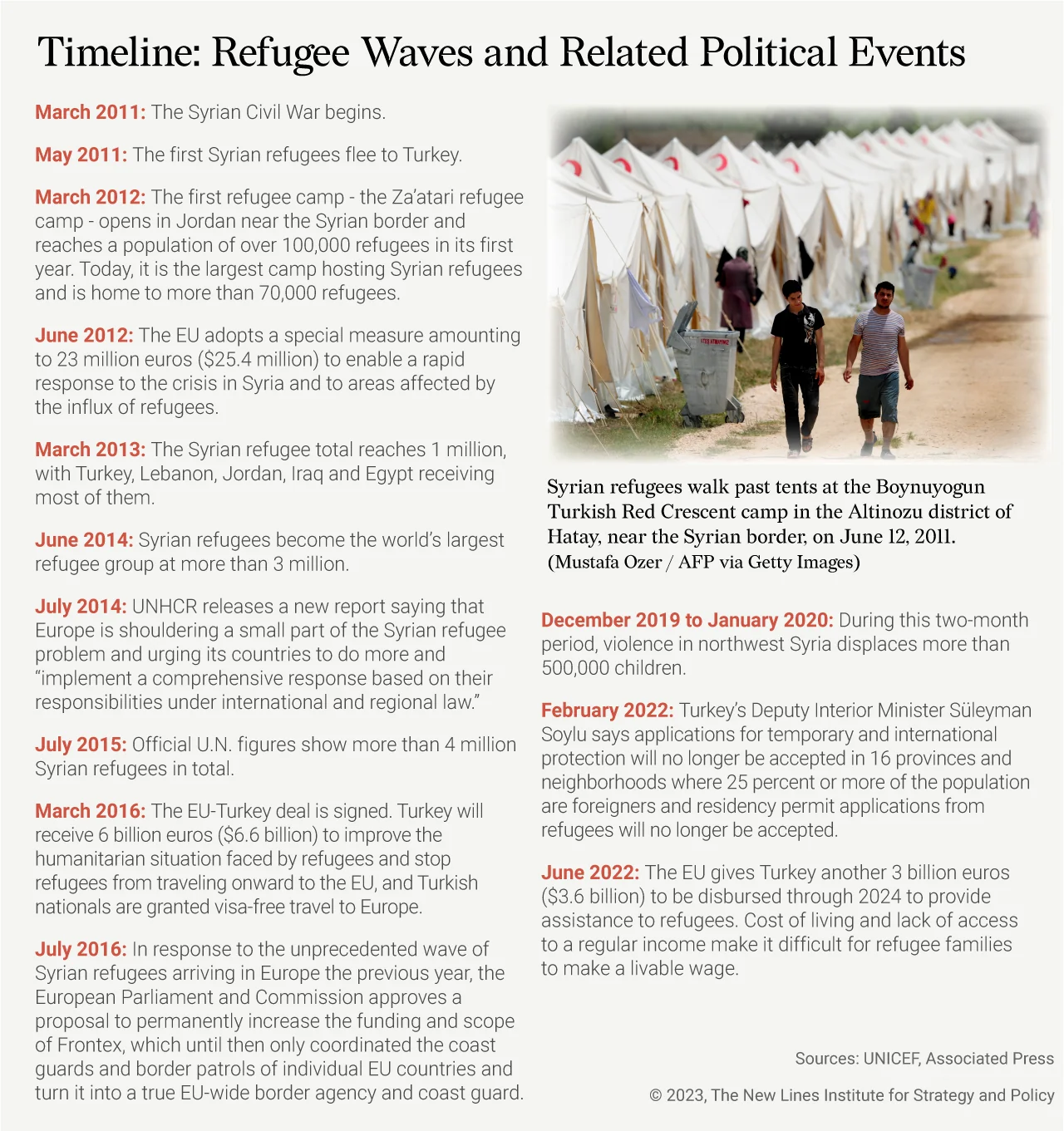

Just over 3.5 million UNHCR-registered Syrian refugees currently live in Turkey, comprising the largest registered refugee population in the world. Hundreds of thousands of unregistered Syrian refugees are also estimated to live in Turkey, although the exact number is highly uncertain due to their legal status and heightened risk of deportation. Refugees began fleeing to Turkey in small numbers at the outset of the civil war in 2011, but the largest waves arrived in 2015 and 2016, when a series of brutal offensives by the Syrian regime – backed by the Russian air force and Iranian-funded militias – retook the largest rebel-held cities in northern and central Syria.

Although the number of registered Syrian refugees in Turkey has remained relatively static since 2018, there has been significant change under the surface. Hundreds of thousands of refugees have continued to arrive since 2018, displaced by the regime’s airstrikes in rebel-held Idlib and its offensives to retake the country’s south. These arrivals have been offset by the roughly half a million refugees who have returned to Syria from Turkey since the war started.

As the Syrian civil war has settled into a stalemate, Turkey’s hopes for a quick and easy repatriation process have begun to dwindle, even as Ankara has faced increasing economic and political pressure domestically to resolve the issue. Syrian refugees across the Middle East have become increasingly reluctant to voluntarily return to their home country. In 2022, 92% of Syrian refugees polled in Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, and Lebanon said they did not plan to go home in the next 12 months, up from 78% in 2017. Recent polling data on Syrian refugees in Turkey also indicates that over 60% of the population does not want to return to Syria under any circumstances. Interviews with Syrian refugees, moreover, strongly suggest that even those “voluntarily” returning to Syria are being heavily coerced by the Turkish government.

Building Pressure for Forced Deportation

Even as Syrian refugees have become increasingly reluctant to return to their country of origin, Turkish public opinion has turned against allowing them to remain in Turkey. The Turkish government’s decision to accept refugees was already unpopular in 2012, when a poll found that 66% of Turks believed incoming refugees should be turned away at the border. Since then, rapid inflation (58% annually as of January) and high unemployment (now above 10%) have squeezed pocketbooks in Turkey, and refugees have become a convenient scapegoat for the government, which claims it has spent over $40 billion meeting the needs of Syrians in the country since the war began. Polling in 2021 found that 82% of Turks want Syrians to be deported, up from 49% in 2017, and Syrian refugees in the country now report widespread and intensifying discrimination. Far-right politicians have turned refugees into a wedge issue in Turkey’s upcoming elections, and Erdoğan has faced pressure to demonstrate that he has a plausible roadmap – however questionable from a human rights perspective – to repatriate Turkey’s refugee population soon. The desire to repatriate refugees has led Erdoğan to pursue normalization with Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s regime even as he seeks to expand Turkey’s own occupation of much of northern Syria.

Meanwhile, conditions in Syria have become increasingly hostile to repatriation. As the Assad regime has retaken most of the country’s territory, refugees have become increasingly fearful of forced conscription, targeted reprisals, and food insecurity as the economic situation in regime-held territory continues to deteriorate. Returning “home” is not a realistic option for refugees whose property has already been auctioned off , “sold” to Hezbollah fighters, or appropriated by the regime. These challenges to repatriation were dramatically exacerbated in 2021, when the Syrian government instituted a new law requiring Syrian men (displaced or otherwise) who had not completed their mandatory military service to pay an $8,000 fine or see their property confiscated without notice. Syrian refugees who could not pay the exorbitant fee lost the legal right to property they were forced to leave during the war.

The Turkish government, unable to solve the problems that make voluntary repatriation unrealistic for refugees, has begun to resort to coercion, both directly and indirectly, to get Syrians out of the country. Indirectly, Turkey has begun restricting how many Syrians can live in specific neighborhoods, forcing Syrians to leave provinces with better employment opportunities, and limiting Syrians from accessing the formal labor market. Taken together, these policies serve to degrade the quality of life for refugees in Turkey and make life in Syria – no matter how challenging and dangerous – more appealing by comparison.

Turkish coercion also has in many cases involved forced deportations, in violation of international law and Turkey’s own obligations as a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention. Syrian refugees report being arbitrarily arrested and detained, subjected to inhumane conditions, and pressured to return to Syria, and Human Rights Watch has documented hundreds of cases of Syrian refugees being forcibly returned to Syria regardless of their status as refugees. Refugees who fled Syria have been treated as enemies of the state and “disappeared” in the past, and Syrians in Turkey overwhelmingly express that they do not feel safe returning currently. Turkey is not obligated to take all claims of credible fear at face value, but it is obligated, under the 1951 Refugee Convention, to investigate those claims rather than forcibly deporting refugees on an arbitrary, extrajudicial basis.

These forced deportations also complicate Turkey’s relationship with the EU. In March 2016, in the aftermath of the 2015 migration surge into Europe, the EU and Turkey struck a landmark agreement with the goal of reducing the number of asylum seekers arriving in the EU via the Eastern Mediterranean. The deal stipulated that if Greek authorities determined that migrants arriving in Greece irregularly did not have a right to asylum in the EU, they would be returned to Turkey. In return, the EU would accept the same number of Syrian asylum seekers waiting in Turkish refugee camps and resettle them. The European Union also agreed to reduce visa restrictions for Turkish citizens and pay 6 billion euros, or $6.6 billion US, to Turkey by the end of 2018 to support the country’s refugees. The deal was explicitly a temporary measure, signed when most states still anticipated a near-term end to Syria’s civil war. As a result, the financial incentives provided to Turkey have now dried up even as the war has stretched on into a second decade, leaving Turkey with an indefinite obligation and declining international support to meet it.

While EU leaders viewed the agreement as a success in stemming migration into Europe, the deal hinges on Turkey being a safe country for Syrian refugees. As Turkey ramps up its forced deportations, it is in danger of losing that status. The deportations are a straightforward violation of the principle of nonrefoulement, which prohibits the return of refugees to a country of origin where their safety or freedom would be threatened. The EU is responsible for ensuring Turkey is upholding its human rights obligations, which are a prerequisite for the legal transportation of Syrian refugees from the EU to Turkey. Turkey violating the deal by sending refugees back into Syria demonstrates why migration management must be a joint effort, and not the burden of one country.

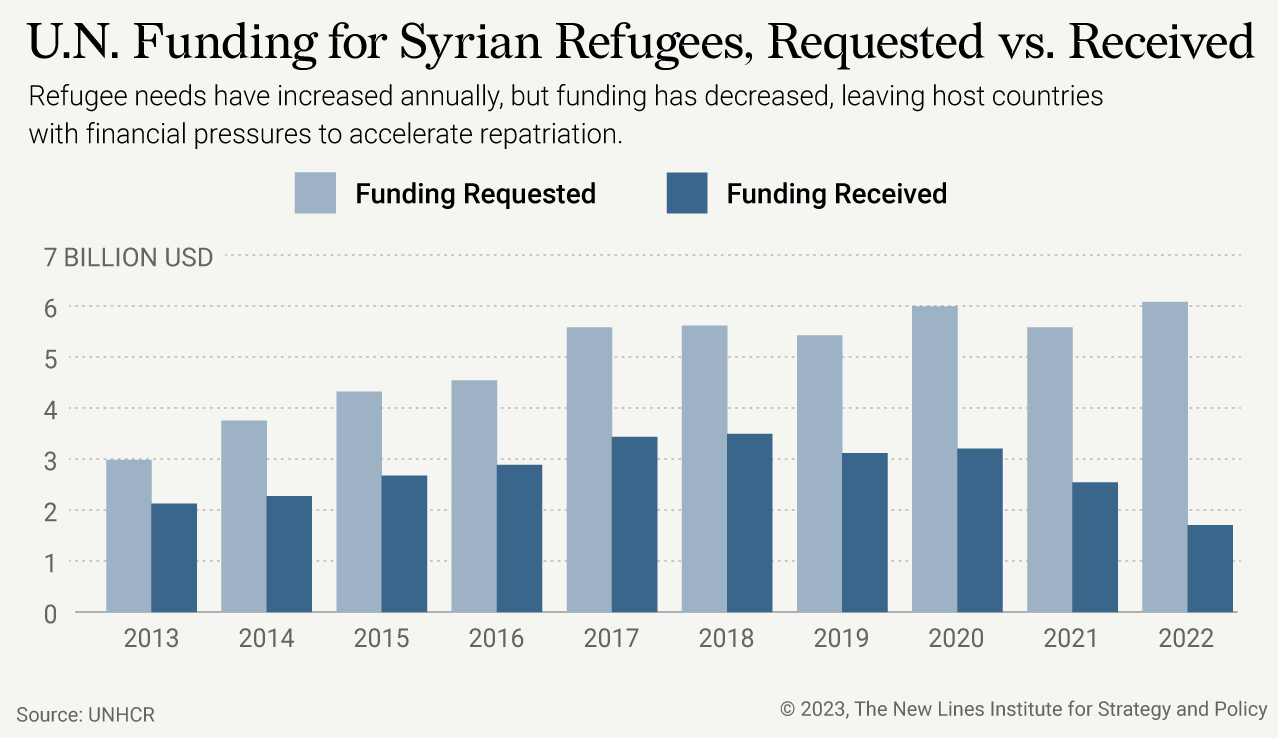

Reduced Funds and Accelerated Forced Repatriation

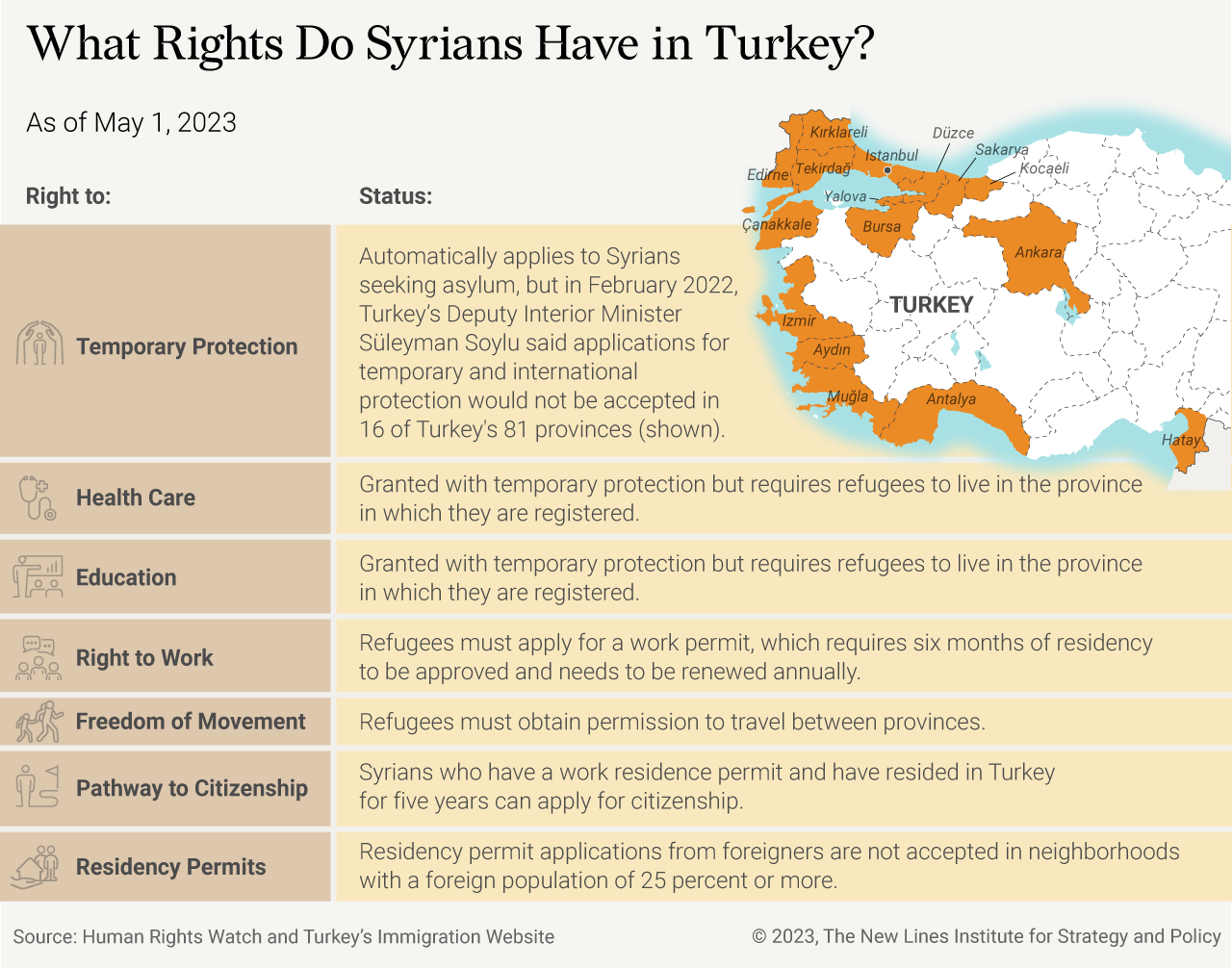

Forced repatriation has likely been accelerated by a combination of economic and social factors, including reduced humanitarian funds that have squeezed Turkey’s capacity to host refugees as well as rising xenophobia in Turkey. Syrians and other refugees from countries to the south and east of Turkey’s borders are granted “temporary protection” rather than full refugee status.

This status grants Syrian refugees access to basic services, including health care and education, but requires them to live in the province where they are registered. Refugees must be granted permission to travel between provinces. Since 2017, Turkish authorities have gradually limited freedom of movement for Syrian refugees in Turkey. In February 2022, Turkey’s Deputy Interior Minister Ismail Çataklı said applications for temporary and international protection would no longer be accepted in 16 provinces. He also announced that in any neighborhood in which 25 percent or more of the population consisted of foreign residency permit applications by refugees would not be accepted.

While the European Union has continued to offer financial support to refugees in Turkey, greenlighting a plan last June that gave Turkey another 3 billion euros ($3.6 billion) to be disbursed between 2022 and 2024, because the cost of living and lack of access to a regular income make it difficult for refugee families to make a livable wage. In recent years, Turkey has faced deepening debt and poverty due to the secondary impacts of COVID-19 and the depreciation of the Turkish lira.

Racist and xenophobic attacks against foreigners, and most notably Syrians, in Turkey have increased in the past two years. On Aug. 11, 2021, groups of Turkish residents attacked Syrian homes and workplaces in Ankara. Opposition politicians have made speeches in the lead-up to general elections in spring 2023 that fuel anti-refugee sentiment and suggest that Syrians should be returned to Syria. These incidents have deepened existing pressures between the host country and refugee communities, and Erdoğan’s coalition government has responded with pledges to resettle Syrians in Turkish-occupied areas of northern Syria.

Beyond the benefits Syrian refugees receive from the Temporary Protection Regulation, Syrians also participate in the labor market, despite obstacles. Refugees must apply for a work permit, which requires six months of residency for approval and must be renewed annually. Because of this, many Syrians face added pressure to participate in the labor market informally, in sectors with lower wages and precarious conditions such as construction and agriculture. In an attempt to expand labor market access, the Turkish government exempted Syrians employed as seasonal workers in agriculture from needing work permits, but since the majority of employment in the agricultural sector in Turkey is informal so the effect of this move was muted.

Policy Recommendations

The recent deportations demonstrate that Syrians transported to Turkey face a small but growing risk of refoulment to Syria. If Turkey moves forward with plans for mass deportations, in line with Kılıçdaroğlu’s campaign-trail proposal, the EU-Turkey deal will be upended. The EU has thus far been able to ignore the relatively modest number of forced deportations, but if Turkey scales the policy up to send millions of Syrians back to unsafe conditions, the EU will be unable to ignore the crisis and will be left with no credible partner to stem the flow of refugees into EU member states.

To avert this potential crisis, the European Commission should signal to Turkey that it is at risk of losing its status as a safe third country set out in Article 38 of the EU Asylum Procedures Directive, and that continued refoulment will jeopardize EU refugee aid money to Turkey, which is predicated on the latter country’s commitment to hosting refugees in safe and humane conditions.

The European Union should use its bilateral relationship to reiterate the importance of upholding the human rights of refugees in Turkey. Beyond the European Commission publicly calling on the Turkish government to stop the deportations and human rights violations happening to Syrian refugees, the EC should work with UNHCR to implement a third-party monitoring system that can determine whether Syrians leaving Turkey are doing so voluntarily or if they are being forcibly deported.

In addition to renewed diplomatic pressure and monitoring mechanisms, the EU should offer Turkey a longer-term framework for hosting Syrian refugees as the prospects of safe near-term repatriation dwindle. Current EU payments to Turkey are made on an ad hoc basis and bear little relationship to the actual financial challenges of hosting the world’s largest registered refugee population. A long-term, annual funding pledge agreed upon by both parties, in exchange for third-party monitoring and an end to forced repatriation, would disincentivize Turkish efforts to solve this challenge through unilateral deportations.

The United States, meanwhile, should seek opportunities publicly and privately to pressure Turkey against forced and coerced repatriation of Syrian refugees who do not feel safe returning to their country of origin. The State Department’s 2022 edition of its annual Human Rights Report, expected to be published in the coming months, is a key way to communicate to Turkey that it is monitoring this issue closely. The 2021 report made limited mention of “some cases” of Turkish refoulement of refugees, and the 2022 report is an opportunity to highlight that this issue has grown more acute in the past year.

Washington should communicate that its funding for the Syrian refugee crisis comes with expectations for how refugees will be treated by the countries receiving funds. The U.S. is by far the largest single donor to the Syrian refugee crisis in Turkey and the region as a whole, donating $239 million to Turkey in 2022, and it has considerable financial leverage to ensure host countries are meeting their human rights obligations in exchange for funding. Just 39% of the U.N.’s 2022 funding appeal for the regional crisis was met, and declining annual support leaves Turkey and neighboring countries increasingly willing to seek unilateral solutions to the crisis. The United States should reverse its years-long trend of reduced funding for the crisis, in exchange for a clear pledge from local governments to uphold basic human rights standards for refugees. The U.S. could also use its funding as a pressure point to dissuade Turkey from normalizing relations with Syria.

In addition to this pressure, however, the White House should look for opportunities to show Ankara that it can be a partner in meeting this challenge, provided Turkey adheres to human rights standards. The United States has already volunteered $185 million in relief funding following the earthquake in Turkey and Syria, and it should consider donating additional funds for reconstructing hard-hit cities in southern Turkey, where housing shortages are likely to form a new pretext for deporting Syrians.

Although neither the United States nor Turkey can solve the deeper problems that make returning to Syria so dangerous for refugees, Washington should look for opportunities to mitigate those problems, to show Ankara that it is serious about helping refugees to return to Syria safely in the long term. Humanitarian funding for the Syrian crisis has dwindled in recent years, exacerbating food insecurity in the country, and Washington should look for opportunities to increase its own donations and rally other donors to do the same.

Alice Hickson is the Digital Media Manager at the New Lines Institute. Prior to joining New Lines, Alice served as the Joseph S. Nye Jr. Intern for the Middle East Security Program at the Center for a New American Security (CNAS), and the Council on Foreign Relations’ editorial team. During her time studying in Jordan, she conducted independent research for her thesis on Palestinian refugees and the right of return. Alice holds a Bachelor of Arts in International Relations and Middle Eastern Studies from Tufts University. She tweets at @_AliceHickson.

Calvin Wilder is an Analyst for the Nonstate Actors program at the New Lines Institute. Prior to joining the institute, Calvin was a Research Assistant at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy’s Program on Arab Politics, a Research Assistant on the Chicago Project for Security and Threats’ Arabic Propaganda Analysis Team, and a Boren Scholar in Amman, Jordan. Calvin holds a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science from the University of Chicago. He tweets at @CalvinWilder.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of the New Lines Institute.