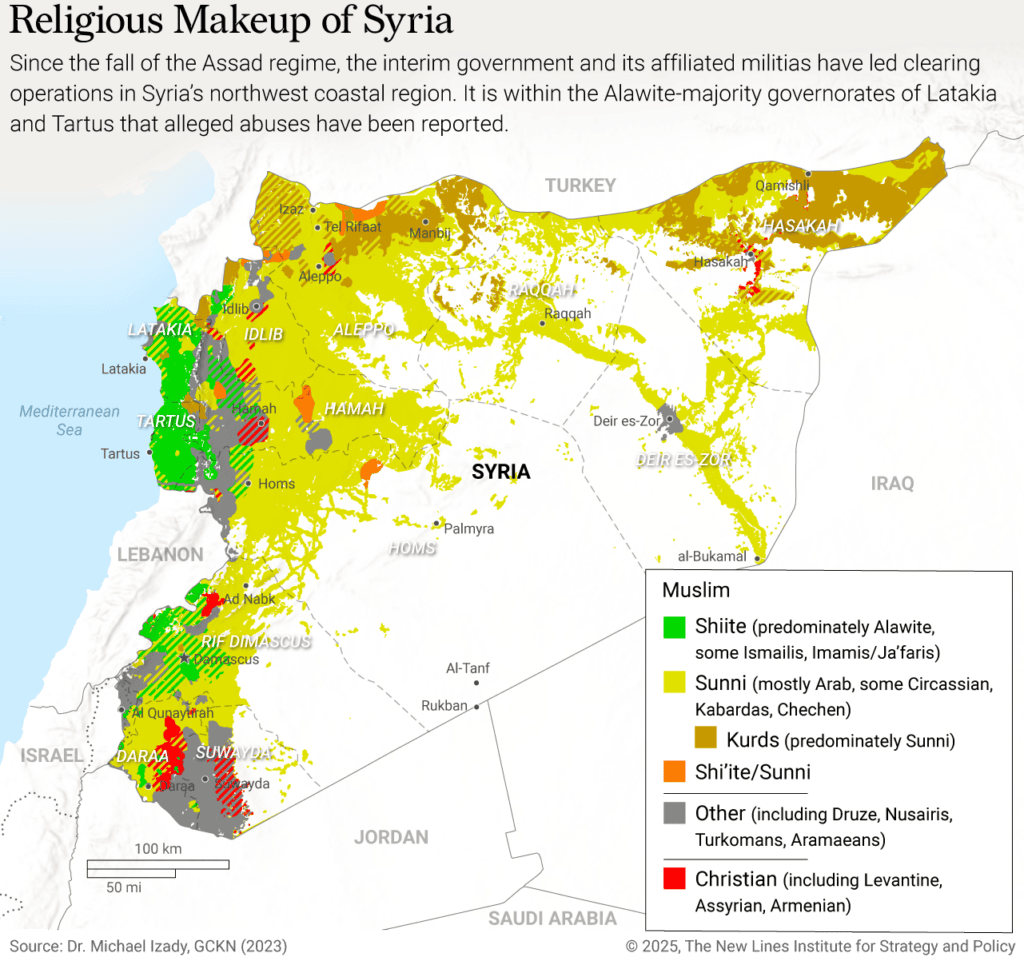

Fighters loyal to former Syrian President, Bashar al-Assad, attacked the coastal town of Jebleh on March 6, killing 13 members of the interim government’s security forces. This incident would have deadly consequences for Syria’s minority communities. In response to the insurgency, government-aligned militias from Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS)-controlled Idlib, carried out reprisal attacks on Alawite, Christian, and Druze communities in the coastal region of northwest Syria. The U.K.-based Syrian Observatory for Human Rights (SOHR) documented the deaths of 973 civilians, including women and children, between March 6 and March 10. This was the most lethal assault on minority communities since the HTS-led coalition toppled the Assad regime in December 2024.

Numerous allegations of complicity in sectarian violence, civilian intimidation, and the destruction of religious sites have been levied against the Military Operations Command (MOC), a loose coalition of Syrian militias headed by HTS, since it seized power. An analysis of these allegations reveals a pattern of sectarian behavior dating back to the formation of the interim government. The latest attacks against majority-Alawite areas led to thousands of civilians fleeing to neighboring Lebanon. Policymakers must monitor these allegations and ensure that sanctions relief for Syria is contingent on religious minorities being free from persecution.

Alawites in Transition

There has been a long history in Syria of persecution of Alawites, who were not formally recognized as Muslims until 1932. The status change came about only after the grand mufti of Palestine, Hajj Amin al-Husseini, looked to garner more support for his fatwa against French colonial rule. Despite this decades-old status, many within the Sunni majority in Syria still view Alawism as heretical.

Under the presidency of Hafez al-Assad, himself an Alawite, the social and economic conditions for Alawites improved dramatically. For nearly 50 years, the Assad regime appointed fellow Alawites to key positions in the army, intelligence services, and government departments. Elite units, such as the infamous Fourth Armored Division, headed by Bashar’s brother Maher al-Assad, recruited officers almost exclusively from the Alawite sect. This led to Alawites being regarded as the base of support for the Assad family.

With the collapse of the Assad regime, the future social and economic status of Syria’s Alawites became uncertain. In rebel-held areas, Alawites had previously been removed from top positions in government and the security services. This was the case in HTS-controlled Idlib, where critics have argued that the so-called de-Baathification of the army and civil service was, in reality, a process of de-Alawisation. There is anxiety within Alawite communities that the same will now happen in the newly captured governorates.

HTS leader and interim Syrian President Ahmed al-Sharaa has attempted to allay these concerns by promising not to impose sharia restrictions on religious minorities. But even policies that on the surface do not appear sectarian will likely leave Alawite communities worse off under the new government. A good example of this are the plans to roll back Syria’s oversized civil service, which will disproportionately affect Alawites who are overrepresented in the public sector. This will leave many within the minority community feeling uncertain about their future.

In the meantime, the interim government has been vocal in its support for plurality. Foreign Minister Assad Hassan al-Shaibania, speaking at the World Government Summit in Dubai, stated that “contrary to the previous Syrian regime, we have honored diversity since day one.” It is this repeated assertion that has helped garner international support for sanctions relief and normalization. The European Union’s Foreign Affairs Council has reached a political agreement on a roadmap for suspending sanctions, and the U.K. has lifted sanctions on 24 Syrian entities, including the Syrian Central Bank.

The timing of these policies is likely premature. On March 7, the same day the EU tabled a motion for the removal of sanctions on the Syrian Central Bank, Alawite, Christian and Druze civilians were being executed by government-aligned militias in northwest Syria. As it stands, the roadmap for sanctions relief is out of sync with realities on the ground.

Reprisal killings in the Latakia and Tartus governorates are the latest, and most deadly, iteration in a series of alleged attacks on minority groups. Allegations of MOC complicity in sectarian violence, intimidation, and cultural vandalism have been increasing, putting into question the credibility of al-Sharaa’s caretaker government. This escalating pattern of sectarianism has already undermined efforts toward national reconciliation and has revealed the interim government’s inability to govern inclusivity or restrain the more radical, Islamists factions within its ranks.

MOC Targeting Alawite Communities

The Alawite Islamic Forum in Syria, on Jan. 3, released a statement that expressed support for the interim Syrian government but accused the MOC of sectarian-motivated attacks against Alawite communities in Homs, Hama, Latakia, Tartus, Damascus, and Daraa. HTS-led clearing operations in Alawite majority neighborhoods led to a flurry of allegations of civilian intimidation, illegal searches, and inhumane treatment.

The SOHR obtained footage of the MOC targeting civilians in the Alawite neighborhoods of al-Zahraa, al-Arman, al-Sabil and al-Muhajereen in the city of Homs. Civilians were made to bray like animals and were intimidated with gunfire. The actions of the MOC were described as “Shabiha-like” – a reference to the notorious criminal gangs used by the Assad regime to intimidate and murder civilian opposition.

Around the same time, the MOC was accused of cultural vandalism against Alawite sites. SOHR activists in Homs reported several attacks on cemeteries in the predominantly-Alawite neighborhoods of al-Zahraa and Wadi al-Zahab. The MOC also has been accused of damaging Alawite houses, tombs, and other cultural sites. These allegations fly in the face of al-Shaibania’s promise to honor diversity.

Attacks on religious sites have been a source of growing agitation between Alawites and the interim government. Journalist Kamal Shahin, writing for New Lines Magazine, reported on the mass protests in Homs, Latakia, Jebleh, and Tartus after the destruction of the shrine of al-Khasibi, the founder of the Alawite sect, in Aleppo. These sites are protected under the Hague Convention, and a recent ICC ruling affirmed that “directing attacks against historic monuments and buildings dedicated to religion” constitutes a war crime.

It is not just Alawite communities that have been targeted since the takeover. In the Christian-majority town of Suqaylabiyah, on Christmas Eve 2024, unknown individuals burned down the town’s Christmas tree,and there have been reports of Druze shrines being desecrated. These incidents will strike a chord with those who still believe that Sunni Islamism represents an existential threat to religious freedoms and will likely undermine buy-in to the new political settlement.

There have also been numerous documented reprisal killings since the MOC took power. Although al-Sharaa has given amnesty to former regime conscripts, he has also promised to bring to justice – through the judiciary – those who committed crimes under the former regime. There have been frequent examples of extrajudicial killings of those accused of crimes. The public execution of Mazen Kneneh, who was tied to a tree and shot in the head after being accused of writing malicious reports for the former regime, was one such incident that garnered international attention.

The SOHR has also reported an uptick of Alawite assassinations since the MOC came to power. Alawite Sheikh Ali Deeb Abu Rami and his wife were assassinated in Sanidah village; the house of former pro-regime singer Baha’a Al-Youssef was invaded and two women there were killed; and three members of the Alawite-backed National Reconciliation Initiative were murdered in drive-by shootings in the Tartus governorate. The identities of the perpetrators are unknown, but these acts of violence are likely to increase anxiety within Alawite communities.

More is known about the groups involved in recent attacks on minority communities in the Tartus and Latakia governorates. Following the insurgent attacks in Jableh by Assad loyalists, U.S.-sanctioned militia factions from the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army (SNA), namely Jaish al-Sharqiya, Sultan Suleyman Shah, and the Hamzah Division, were directed to Alawite-majority areas to root out regime loyalists.

There have been widespread allegations that these militias have carried out reprisal killings against civilians from religious minorities. The U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights, Volker Türk, gave a statement in which he described “disturbing reports of entire families, including women, children, and hors de combat fighters, being killed.” Footage is available online that shows dozens of deceased men in civilian clothing outside a house in al-Mukhtareyah. It was the deadliest attack on minority communities since the interim government took power.

Implications for Syria

The attacks on civilian populations in Tartus and Latakia reveal significant command-and-control weaknesses within Syria’s security apparatus. The interim government is responsible for the actions of those groups under its formal command, including the SNA. Its inability to prevent these crimes highlights its limited control over militias beyond its traditional base. Al-Sharaa has launched a “fact-finding committee” to investigate the civilian killings in Tartus and Latakia and has promised to hold those responsible accountable. It is to be seen whether this process will restrain radical Islamist groups under the interim government umbrella.

The government-led disarmament program has been the first casualty of attacks on minority communities. Al-Sharaa has promised to disband militia groups and tighten restrictions on the proliferation of arms. However, with resurgence in sectarian-motivated violence, minority groups have started to rearm. Druze militants in Suwayda announced in February 2025 the formation of the Suwayda Military Council, a coalition of local armed groups, aimed at safeguarding civilians and public property. Alawite community groups will likely follow suit and will be reluctant to voluntarily lay down their arms in the face of sectarian attacks.

More worryingly for the interim government, these allegations could drive religious minority groups to support Assad loyalists. There has been kinetic support for the former regime since the interim government took power. On Dec. 26, 2024, loyalists carried out a successful ambush in the port of Tartus, killing 14 members of the security forces. There remain holdouts for loyalists within Syria, including the former rebel warlord Ahmad al-Awda and numerous Druze factions. These groups will likely benefit if Alawites and other religious minority groups are alienated from the new government.

It will also provide a glimmer of hope for the leadership of the former regime. Assad and his family fled to Russia as his government fell, and there are thousands of elite troops of the former regime that escaped to neighboring Iraq. Videos circulated on X (formerly twitter) showed armored personnel carriers belonging to the Fourth Armored Division making their way across the Syria-Iraq border shortly before the fall of the regime. These actors have an interest in spoiling the peacebuilding settlement and can play on the anxiety felt by minority groups.

Rising sectarian violence could also change the demography of Syria, turning coastal regions into Alawite strongholds. This has historical precedent. There were attempts under French colonial rule to make an Alawite statelet on the coast of Syria in 1920. It is likely that increased persecution of Alawite communities in urban centers such as Homs, Latakia, and Tartus will mean that this region will once again become a refuge. Demographic shifts will likely be accelerated by the targeted massacres of Alawites by government-aligned groups.

However, the most worrying implication for the interim government is that sectarian violence risks undermining international support for sanctions relief. In a joint statement on Dec. 14, 2024, the Arab Contact group on Syria and representatives from the U.S., U.K., EU and Gulf states stressed the importance of upholding human rights, especially for women and religious minorities. Reports of violence have not stopped progress on sanctions relief thus far, with the EU and U.K. loosening sanctions. However, the most recent attacks on civilian populations will likely give policymakers pause for thought.

U.S. Sanctions Policy Toward Syria

The United States has the most comprehensive sanctions policy toward Syria. The country was designated a State Sponsor of Terrorism in 1979 and has been subject to economic sanctions under the Syria Accountability Act in 2004. This legislation prohibits the export and re-export of most U.S. products to Syria and has had a crippling effect on the Syrian economy for two decades. Additional sanctions were issued in 2012 under Executive Order 13894 in response to human rights abuses, and the Caesar Syria Civilian Protection Act of 2019 allowed the president to sanction those who supported the Assad regime.

U.S. sanctions policy toward Syria has an extraterritorial component. The Foreign Assistance Act means that third parties can be penalized if they trade with sanctioned countries. The Foreign Assistance Act, the Caesar Act, and other U.S. sanctions have created a punitive framework that makes it difficult for any country to trade with the Syrian economy effectively. The interim government has inherited a highly restrictive sanctions regime that is inhibiting growth and driving inflation.

Although U.S. sanctions exempt humanitarian aid, the provision of support is being made more complicated by the fact that HTS is a proscribed terrorist organization. Al-Sharaa has been on a U.S. terrorism watch list since 2013. This has proven to be a major issue for the government in HTS-controlled Idlib, where humanitarian organizations found it difficult to work with the local authorities due to their terrorist designation. While some U.S. partners are pushing for a roadmap toward normalization, U.S. policy has acknowledged the history of terrorism within those groups that overthrew Assad late last year. Reports of sectarian targeting will only further complicate the already complex path toward normalization.

The U.S. did temporarily ease some sanctions on Syria in the immediate aftermath of the fall of the Assad regime. The Treasury Department issued the Syria General License (GL) 24, which eased restrictions for the provision of essential services relating to the electricity, energy, water, and sanitation for six months. This waiver will allow U.S. companies and persons to export and re-export, subject to case-by-case review by the Department of Commerce. It also temporarily lifts restrictions from the Foreign Assistance Act, allowing U.S. partners to provide aid to Syria.

However, in addition to being temporary, these waivers are not sufficiently drastic to improve the humanitarian crisis in Syria as the bulk of the U.S. sanctions still apply. There are still blocks on the inflow of foreign investment into Syria and trade with Syrian companies. The U.S. has not removed sanctions on Syria’s Central Bank or on assistance to Syria by international organizations. The waivers should not be seen as a decisive shift in U.S. sanctions policy toward Syria.

The HTS terrorist designation remains a sticking point. U.S. policymakers must ascertain how far al-Sharaa and HTS have moved from their al Qaeda roots. This process is being carried out cautiously. Although al-Sharaa remains on the U.S. terrorism list, the U.S. has cancelled the $10 million reward for his capture. The Senate Foreign Relations committee has indicated that normalization is more likely to be achieved if al-Sharaa can ensure a peaceful transition, effective demobilization of armed groups, and commitment to the 1974 disengagement treaty with Israel.

However, in February, the committee warned that “international engagement with the new leadership in Syria is outpacing U.S. policy.” Al-Sharaa made his first foreign trip to Saudi Arabia, where he and Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman discussed Syrian reconstruction. There have also been positive steps made toward normalization with European nations. It is the position of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee that if the U.S. cannot lift sanctions altogether, it should at least adopt a policy of “not getting in the way” and allow partners to help revitalize Syria’s economy. This would likely mean an amendment to the Foreign Assistance Act and Caesar Syria Civilian Protection Act.

This is unlikely to happen if the Syrian government remains complicit in sectarian violence against religious minorities. It is U.S. policy that the next government must “fully respect the human rights and fundamental freedoms of all Syrians.” Allegations of violence, intimidation, and cultural vandalism by the MOC will put in question interim government’s commitment to those rights. The recent attacks by government-aligned militias in Tartus and Latakia has likely set back sanction relief talks. In a March 9 statement, U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio insisted that “Syria’s interim authorities must hold the perpetrators of these massacres against Syria’s minority communities accountable.” A more permanent sanctions relief policy is not likely to come while it remains unclear how far removed al-Sharaa is from his al Qaeda roots.

Recommendations

U.S. sanctions relief should be contingent on the next government of Syria upholding human rights for minority groups. This has been a central policy objective by the U.S. and its allies since the interim government took control of Syria. It is imperative that any roadmap toward sanctions relief has a monitoring component that can identify and assess allegations of sectarianism committed by the Syrian government.

- The Senate Foreign Affairs Committee should work with nongovernmental organizations like Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, and the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights to monitor and assess allegations of crimes against religious minorities.

- The U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Near Eastern Affairs should pressure the interim government to guarantee the rights of religious minorities in Syria.

- The U.S. Mission to the U.N. should encourage the U.N. Commission of Inquiry on Syria to investigate alleged war crimes against Alawite communities by the MOC since HTS took control of Syria.

- Identifying perpetrators of sectarian violence is a priority, and those individuals should be sanctioned under the Caesar Syria Civilian Protection Act.

- The U.S. Mission to the European Union should underscore the U.S. commitment to minority rights in Syria and emphasize that an EU roadmap toward sanctions relief must be contingent on religious tolerance.

- The U.S. administration should put pressure on Türkiye to help demobilize the SNA, which is undermining the command-and-control hierarchy of the interim government and has committed human rights abuses.

The United States and its partners are still trying to determine what type of government will emerge in Syria. Al-Sharaa has repeatedly underlined his commitment to minority rights in a move designed to show that he has grown past his jihadist roots. This issue will likely be the litmus test by which the new government in Syria is judged. Allegations of violence against Alawite communities by the MOC puts in doubt the new regime’s commitment to minority rights. The United States should monitor allegations of sectarian violence and make sanctions relief contingent on the rights of religious minorities in Syria being upheld.

Ralph Outhwaite is a graduate of King’s College London with a master’s in Conflict, Security and Development. He is a contributor to The Spectator magazine and completes civilian impact assessments of airstrikes in the Middle East for a nonprofit. His research explores defense issues, illicit supply chains, and geopolitical strategies in Europe and the Middle East.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of New Lines Institute.