As Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine continues into its third year, Ukrainians are grappling with both the war’s devastating effects and how to contextualize it in their cultural memory. Ukraine’s complex experience of the early 20th century and World War II has resulted in unique memory politics that have trended toward anti-Russian sentiment. In the current war, this has manifested in the increased popularity of Ukrainian historical figures and movements with ties to Nazi Germany.

This sentiment has been the source of tensions between Ukraine and its Western allies – especially Poland, a key logistical partner in the current war. If Ukrainian media and political figures continue their veneration of problematic historical figures, the possibility of Western condemnation will increase significantly, creating additional hurdles for Ukraine to receive military aid, especially from governments – including a possible incoming U.S. presidential administration led by Donald Trump. To maximize Ukraine’s ability to maintain support for its war effort domestically and abroad, it is important that U.S. policymakers be aware of Ukraine’s potential alienation from NATO allies and guide Ukrainian policy and media toward historical veneration that does not cause contention with allies.

Legacy of the “Great Patriotic War”

Remembrance of World War II is particularly powerful in the post-Soviet sphere, whose modern characteristics are shaped by Soviet-era remembrance policies. Referred to in the region as the “Great Patriotic War,” it is circumscribed to the Eastern Front after the German invasion and ignores the USSR’s early collaboration with Adolf Hitler and invasions of Poland, Finland, the Baltics, and Romania. Such circumscription allowed the USSR, especially Russia, to paint itself as a triumphant victim.

This narrow view of the war even extended to the Holocaust. While the Soviets did not deny the Holocaust, it was a small part of the historical memory of the Great Patriotic War. Instead, the Soviets focused on attempts by the Nazis to destroy the USSR and the Slavic race. This dynamic illustrates the pervasiveness of the Soviet historical memory, which was able to portray the Holocaust as a Soviet-centric event.

These views of the Great Patriotic War continue, especially in Russia. Russian society, both through state-sponsored media and popular opinion, has continued to tout the war as a central part of state consciousness. Even through the tumultuous 1990s, more than 80% of Russians considered World War II to be the most important moment in the nation’s history, and this sentiment remains. Russia even enshrined the memory of World War II with a 2020 constitutional amendment that makes it illegal to downplay the Soviet role in winning the war, a law far more overarching and vague than memory laws in other nations. This year, Russia chose May 9, a holiday known as Victory Day that commemorates the Soviet victory of World War II, to launch a new offensive against Kharkiv.

Ukrainian Nationalism

By contrast, Ukraine’s modern cultural memory is colored by inter-war calamity and the World War II Ukrainian nationalist movements. Of these, the latter has the potential to directly conflict with Western sensibilities and create tension between Ukraine and its allies.

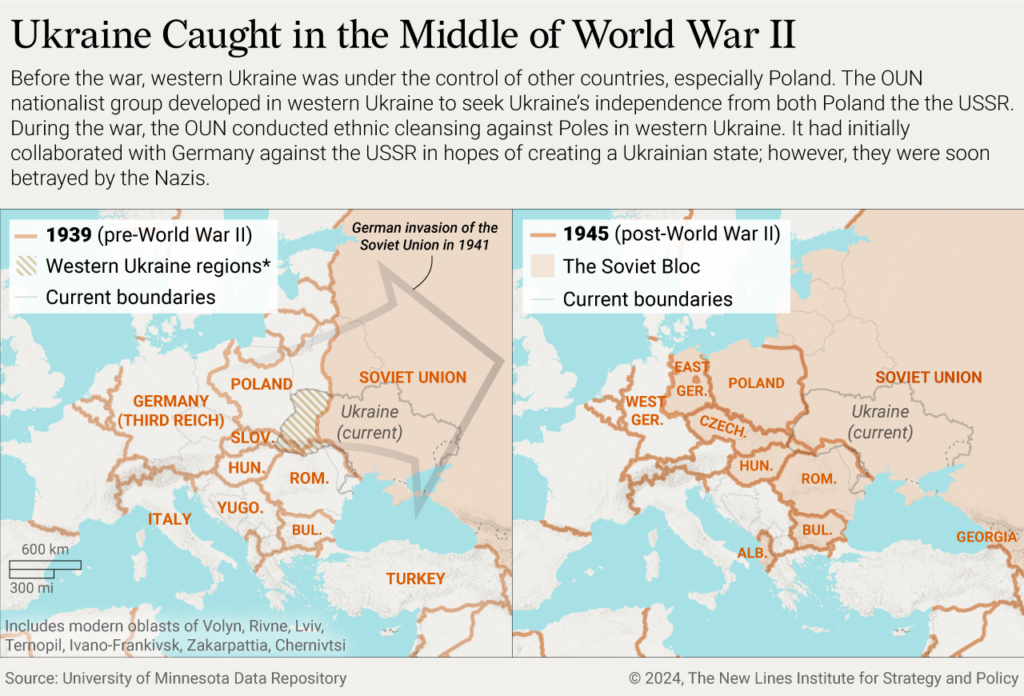

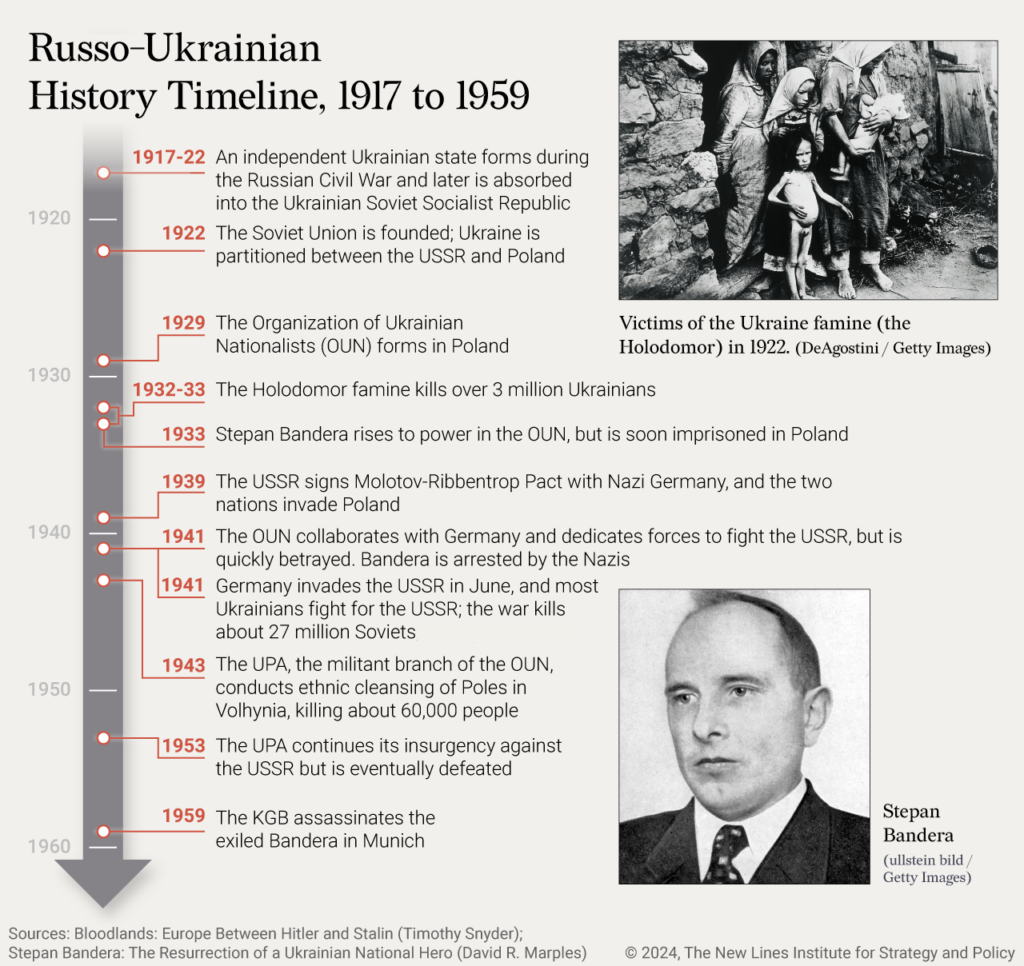

Much of the controversy centers on the increasing veneration of a World War II-era far-right Ukrainian nationalist group, the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), and its leader, Stepan Bandera. The OUN’s aim was to break Ukraine away from the Soviet Union and create an independent state, and to this end, it collaborated with the Nazis and provided troops in the early days of their invasion of the USSR. The military branch of the OUN, the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (OUN-UPA), also conducted ethnic cleansing campaigns against Poles, Jews, and other ethnic minorities.

In 2010, then-Ukrainian President Viktor Yushchenko awarded Bandera the Hero of Ukraine medal, igniting a more public discussion of the Ukrainian national movement during World War II. Under Ukraine’s next leader, President Viktor Yanukovych, who had a strong voter base with eastern and pro-Russian voters, the rehabilitation of the OUN’s image was curtailed by the government, and Bandera’s medal was rescinded. The debate reemerged during the 2013-2014 Euromaidan protests, which ushered in President Petro Poroshenko’s more pro-Western government. Poroshenko appointed controversial polemicist Volodymyr Viatrovyich to be head of the Ukrainian Institute of National Memory. Viatrovyich developed a reputation as a motivated nationalist, on various occasions stating that academic practice should be subordinate to national mythmaking and that the OUN must be held up as heroes.

Another critical moment for Ukrainian historical memory came in 2015 with the passage of four “decommunization” laws. The bills elevated the controversial Ukrainian national heroes while purging the country of Soviet influence on the political level. Impactful measures included renaming and tearing down public communist commemorations, renaming the “Great Patriotic War” to the “Second World War,” christening Bandera and the OUN-UPA as freedom fighters, and outlawing “public displays of disrespectful attitudes” toward them. These laws, prepared by the Ukrainian Institute of National Memory, were passed without public or parliamentary debate.

Ukraine’s struggles with the legacy of Bandera and the OUN have most affected its relations with Poland, which plays a key role in NATO’s military support for Ukraine. Poland’s border serves as the critical method of getting aid into Ukraine, and Poland itself has donated over 4 billion euros to Ukraine’s war effort and recently entered into a bilateral security agreement. Tensions between the two countries increased in 2015 after a prominent street in Kyiv was renamed after Bandera on the anniversary of the Volhynia Massacre, in which approximately 60,000 Poles were killed by the UPA. In response, the Polish Parliament declared July 11, 2016, a day of remembrance for the victims of the Ukrainian genocide against Poles, which the Ukrainian parliament in turn condemned. In 2021, the government of the Ukrainian town of Ternopil renamed a stadium after a OUN-UPA war criminal, drawing condemnations from Ukraine’s Polish and Israeli ambassadors, as well as suspension of relations with the nearby Polish town Zamość. The next year, Ukraine’s ambassador to Germany denied Bandera’s role in war crimes against Poles, sparking more controversy. The Ukrainian Foreign Ministry initially dismissed the ambassador, but months later he was promoted to deputy foreign minister of Ukraine. In January 2023, Ukraine’s parliamentary account posted a picture on X (formerly Twitter) of Ukraine’s then-Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces Valerii Zaluzhnyi under a portrait of Bandera. The post was soon taken down, but not before drawing condemnation from Poland’s prime minister and other senior Polish government officials.

Less contentiously, the notion of Ukrainian historic victimhood at the hands of the Soviets increased at the same time among the Ukrainian population. For example, Ukrainians’ views of the Holodomor, a 1932-1933 famine perpetrated by Josef Stalin’s regime that killed more than 3 million Ukrainians, has shifted, with a 2021 poll showing 85% believed it was a genocide, up from 58% in 2011.

With Russia’s 2022 invasion, Ukrainian public sentiment changed quickly: Positive perception of Bandera increased to 74% in December 2022, up from 36% in 2018. That same year, Bandera entered Ukraine’s top five most admired figures, and the UPA increased in popularity from 47% in 2019 to 81% in 2022. Anti-Soviet perceptions have dramatically increased as well: In 2023, 92% of Ukrainians viewed the Holodomor as genocide. The popularity of Victory Day also dropped; 34% reported a positive attitude toward the holiday in 2022, down from 80% in 2018.

The Great Memory War

Since entering office in 2019, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has made efforts to refocus toward historic Ukrainian victimization rather than nationalist sentiments. These efforts will have their greatest impact on isolationist-minded Western politicians and media figures. With the potential for an incoming Trump administration, which would likely curb the amount of U.S. aid, Ukraine cannot afford to be seen as sympathetic to Nazism or Nazi collaborators. While other considerations are certainly present, it is important that Ukraine reduce its axes of vulnerability and any talking points that can be used to justify cessation of aid.

Pro-Bandera and pro-OUN sentiments in Ukraine have fed into Russian claims of Ukrainian fascism. Russian President Vladimir Putin has routinely referenced the “denazification” of Ukraine. The fact that Bandera, a Nazi collaborator, has become widely popular has played a role in validating this for Russians and their propaganda, exemplified by former Russian President Dmitry Medvedev’s insistence on calling Ukraine “Banderaland.”

Zelenskyy has avoided evoking Bandera as a national hero, and when asked about the topic in 2019, he vaguely maintained that Bandera “is a hero for some Ukrainians.” Zelenskyy, Ukraine’s first Jewish president, has also increased emphasis on the Jewish Holocaust in Ukraine, such as with his condemnations of the Russian strike that hit the Babi Yar monument in Kyiv or with sharing his family stories of the Holocaust.

Despite making this pivot, tensions still persist with Poland. While Zelenskyy attended a Catholic vigil with Polish President Andrzej Duda to commemorate the Volhynia Massacre, his public statement on the matter was vague and did not condemn the OUN or name Poles as victims. Instead, he left enough ambiguity to not contradict the mainline Ukrainian view, which holds that the “massacre” was actually a brutal civil war. Tensions between Poland and Ukraine have also flared over grain exports during the Russian invasion, and various Poles, including the vice speaker of the Sejm, have accused Ukrainian officials of “Banderite language.”

Ukrainian national narratives currently are not too off-putting to the West. It is possible, however, that other figures in Ukraine, especially Zelenskyy’s eventual successor, could amplify the more problematic elements of Ukrainian history. While the war effort remains popular, military recruitment in Ukraine has struggled. The government has recently expanded its conscription age pool to alleviate the personnel shortage, but generals have said they would rather have volunteers instead of draftees who would be less motivated fighters or even flee the country to avoid combat. In a bid to increase popular domestic support and recruitment for the war, Ukrainian media and politicians may lean on the memory of the UPA, especially given the organization’s militancy and parallels with resistance against Russia. A pivot in this direction could have a detrimental effect on critical, hesitant Western figures and sacrifice international support for domestic recruitment.

As language praising Bandera becomes popular among the Ukrainian populace and thus viable for Ukrainian state media, it is important for Ukrainian policy and media figures to avoid going down this path for fear of playing directly into Russian propaganda and alienating allies, particularly Poland.

Policy Recommendations

- Dissuade Ukrainian officials from pro-Bandera/OUN-UPA Language: Ukrainian policymakers, especially in cultural departments and media, should avoid glorifying Bandera and the OUN-UPA, despite their drastic increase in popularity. Keeping Ukrainian figures that do glorify these problematic elements from high positions would be key to this. This is especially important for successive Ukrainian administrations, as many of these figures are appointed by or have been co-opted by (in the case of formerly oligarch-controlled media networks) the Ukrainian executive. U.S. policymakers can dissuade problematic appointments or statements and urge Ukrainian policymakers to keep in mind the polarizing nature of some elements of the history. This should be done behind the scenes to avoid feeding into Russian propaganda.

- Encourage Ukrainian Officials to Continue Highlighting the Holocaust and Holodomor: U.S. policymakers can substitute problematic histories by praising and platforming the preferred Ukrainian historical focuses, namely of the Holocaust and Holodomor. Ukrainian opinions on the Holodomor are far more unified and cohesive than those on the OUN and Bandera and still serve to galvanize the Ukrainian populace against Russia. Holocaust remembrance is a subject that is underserved in Ukraine and wider Eastern Europe compared with the West. Continuing Zelenskyy’s focus on the Holocaust would likely help continue to preempt Nazi allegations from Western sources.

- Encourage Ukraine to Engage Allies with Limited Reconciliatory Action: U.S. policymakers should encourage Ukrainian officials to reconcile the country’s history with neighboring countries, especially Poland, to blunt social tensions between the nations. This reconciliation can take a mild form, such as attending vigils or calling for national brotherhood, as it is unlikely that Ukrainian officials will explicitly denounce Bandera and the OUN-UPA. Doing this ensures better cooperation between Ukraine and NATO’s most interested member in the conflict, maintaining supply routes and economic partnerships.

Robert Kremzner is a graduate student at The George Washington University, pursuing a degree in Security Policy. As an undergraduate at Montana State University, he earned a degree in history, where he primarily focused on Eastern Europe. His interests include Soviet history and legacies, Russian aggression in the region, and the interplay between historical memory and modern attitudes in those countries.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of the New Lines Institute.