New attacks on education in Burkina Faso and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) have shed light on a historical model used by Boko Haram to disrupt and destabilize educational gains within fragile states. The growth of Salafist-jihadist groups and ethnic violence in the Sahel and Central Africa has perpetuated the cycle of attacks on education. These attacks have ripple effects, including increased violence against women, an uptick in recruitment of child soldiers into violent extremist groups, and instability that China and Russia can use to increase their presence in Africa. These continued attacks on education have increased instability and ultimately undermined any progress the international community has made toward stability through education.

The implementation of current initiatives to address armed groups’ violence against children has not been successful. Unless policies are reformed to end the current wars on education, Burkina Faso and the DRC will continue to experience short- and long-term hindrances to societal advancement and development. To counter the negative impact, the United States and its international partners including the United Nations and European Union should consider reforming current strategies such as the Safe Schools Declaration (2015) and UNSC Resolution 2601 (2021), and they should support a localized approach that empowers individuals and provides safe alternatives for children and teachers impacted by school closures.

Historical Attacks on Education

Boko Haram’s Operations in the Lake Chad Basin

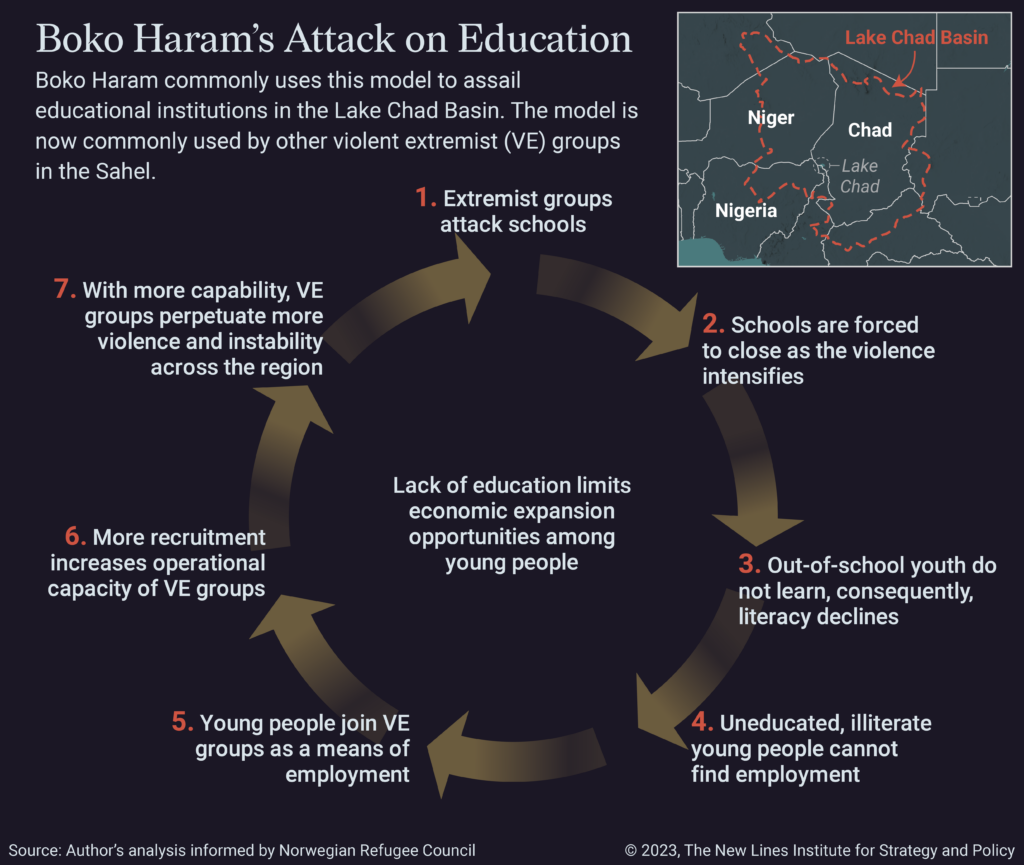

Boko Haram historically has been active at the intersection of Nigeria, Niger, Chad, and Cameroon in the Lake Chad Basin, where the group has subjected millions to violence that has forced numerous schools to close, exacerbating the intense poverty and violence in the region. Boko Haram has used a model for violence against education that is now spreading to the Sahel and Central Africa, creating problems for current and future generations in the region. By targeting schools and kidnapping children, Boko Haram increases its numbers and operational capacity. According to the Department of Justice, the main reason individuals join extremist groups such as Boko Haram or ISIS is to ease social pain and find a sense of belonging. This is coupled with the second-most popular reason: employment. This puts education on the front lines of the battle against extremism.

Boko Haram uses this recruitment model to spread its influence throughout the Lake Chad Basin and further destabilize the region. Boko Haram’s targeting has had an acute impact on young women and girls, as the education of women and girls is seen as pro-Western. That view often leads to increased targeting of coeducational schools.

Boko Haram’s Attacks in Nigeria and Cameroon

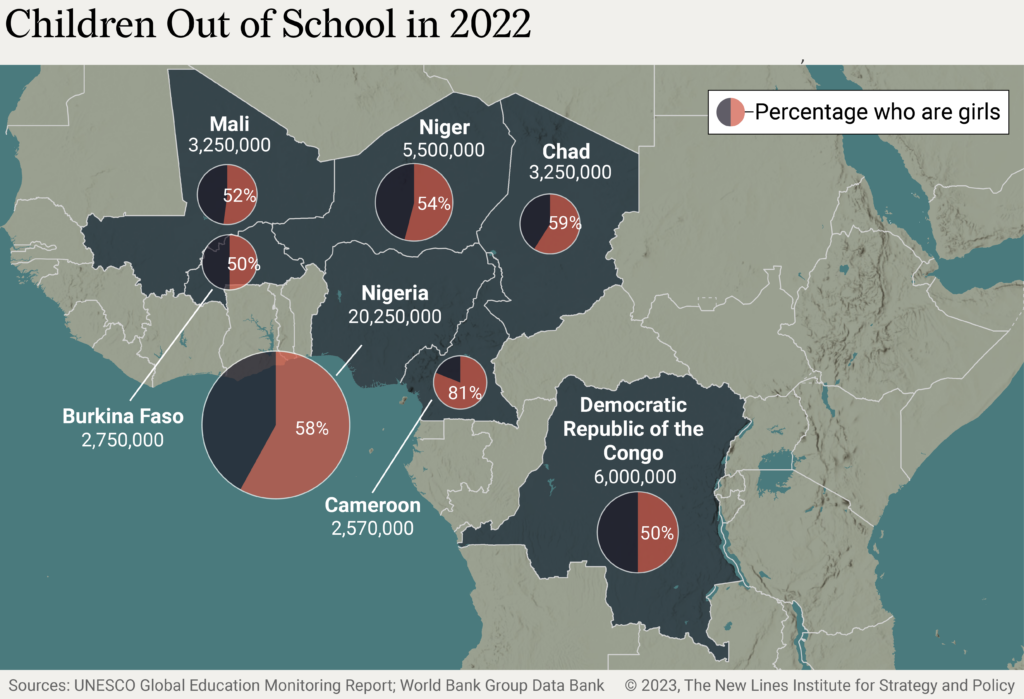

Boko Haram’s attacks on education throughout the Lake Chad Basin have targeted schoolchildren and infrastructure directly through abductions, looting, and arson, resulting in widespread school closures over the past decade. Boko Haram’s attacks gained international attention in April 2014 with the kidnapping of girls from the Chibok ethnic group while at school in northeastern Nigeria. Since their kidnapping, 98 of the 276 abducted girls have remained in captivity, and the Nigerian authorities have not opened an investigation into the security failures that led to their abduction. Kidnapped schoolgirls are subjected to gender-based violence and forced marriages, exemplifying Boko Haram’s cycle of violence against girls. Although Nigerian President Bola Ahmed Tinubu has promised to address school insecurity in his national strategy, combatting the violent insurgency has remained on the back burner, and as instability spreads there are 18.5 million children out of school.

The physical space of schools is not the only target. In Cameroon, Boko Haram has kidnapped children in transit to and from school, as there are no state-sponsored protected routes or official modes of transportation. These increased attacks against students have forced two-thirds of schools to close in Cameroon and driven internal displacement to more secure areas of the country. While internally displaced people (IDPs) hope to improve their access to education, schools that have remained open now suffer from overcrowding and insufficient resources to accommodate the influx of IDPs. There are now 1.4 million children learning in small classrooms that are undersupplied and understaffed.

Attacks on Education Today

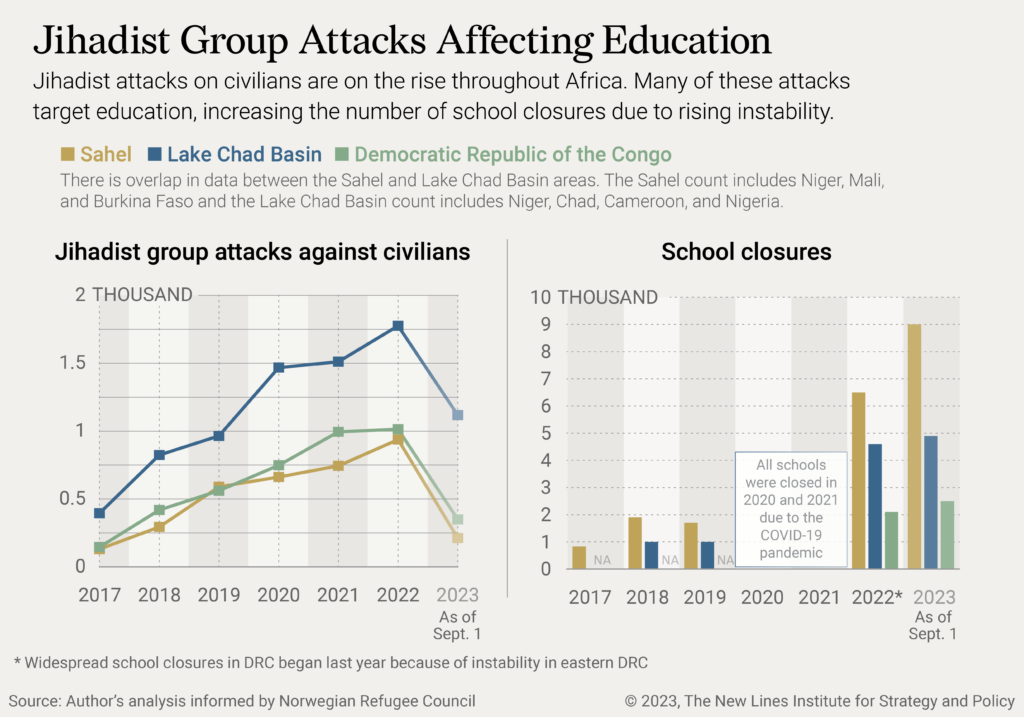

Because of its status as a powerful actor, Boko Haram has inspired other jihadist groups to carry out similar attacks on education elsewhere in Africa. Attacks on education today are more prevalent in fragile states. This fragility can be caused by a multitude of factors such as political coups, failed governmental transitions, systemic poverty, and the rise of extremist groups. These groups often take advantage of fragility to progress their agenda, which includes the closing of schools. In turn, the closing of schools creates a vicious cycle of violence and increases recruitment to violent extremist groups as students and young adults look for means to support themselves outside of inaccessible regular economies. This is most recently represented in the two case studies of Burkina Faso and the DRC, both of which have experienced political unrest, failing economies, and increased extremist violence resulting in extensive school closures. These school closures have resulted in increased instability, which has made these countries vulnerable to exploitation by other international actors such as Russia and China as they look to expand their influence in the region. This puts education at the forefront of great-power competition in Africa.

Case Study: Burkina Faso

In Burkina Faso, the military leadership has struggled to quell violence by al Qaeda-affiliated Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin and the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara, who have capitalized on waning Western interest in the Sahel. These jihadist groups have infiltrated schools armed with guns, opened fire on students and teachers, and sexually assaulted girls, forcing schools across the country to close because of the violence. As of September 2023, a quarter of schools had closed, affecting 1 million students, with the number of out-of-school children expected to increase as the violence continues.

In towns under blockade by militant groups, educational access has deteriorated even further. In the blockaded town of Pama, only two out of eight schools have remained open, and only six teachers are working to educate more than 1,000 students. The blockade has prevented essential supplies from reaching the town and has restricted civilians from leaving for other, more stable regions where children could have better access to education. Jihadist violence compounded by the French withdrawal will increase the number of school closures in Burkina Faso and have long-term impacts on children who will be unable to return to schools and miss out on education.

Case Study: Democratic Republic of the Congo

Extending beyond the Sahel and into the DRC, escalating ethnic violence by armed groups has impacted children in the North Kivu and Ituri provinces. In the 2022-2023 academic year, the deteriorating security situation in the east forced over 2,100 schools to close and deprived 750,000 children of education. The start of the 2023 school year has brought renewed violence against education as armed groups have occupied schools in North Kivu Province and destroyed classrooms, driving one in three children out of schools across the country. Violence has internally displaced 1.7 million people in Ituri Province alone and has raised questions over how to address the education gap among displaced children who are not able to access education because of their temporary and precarious living situations.

Ripple Effects of Education Suspension

These attacks have called attention back to the importance of protecting education and using education as a counterterrorism tool. The attacks represent the resurfacing of an age-old problem in the Sahel and call into question the prevention methods the international community has employed. School closures have numerous detrimental effects on children that can perpetuate instability and violence in the region. Children who are forcibly removed from education are less likely to return due to the deep psychological trauma associated with the violence they have seen and, in some cases, personally endured.

Moreover, children who are displaced will face restricted access to education and will thus have limited long-term employment opportunities. This, in turn, will make them more likely to be recruited by armed militant groups. In attacks on education, girls are increasingly subjected to gender-based violence and are forced to drop out of school, undoing decades of progress previously made on increasing female student school enrollments.

School closures have a direct impact on literacy levels, as children who are out of school quickly fall behind in their educational progress. In the Lake Chad region, youth illiteracy rates are at 70 percent, and lower literacy rates limit opportunities to join the formal economy and find work, which impedes any positive development measures. Nigeria currently has the highest number of out-of-school children in the world, and increasing security concerns in the region are likely to see this number rise. Falling literacy rates have chronically destabilized the region and complicated the long-term paths to progress for youths. As more and more students are removed from school and the population in Africa continues to grow, access to education will be vital in fighting extremism.

Current Efforts

Safe Schools Declaration

Ongoing efforts to secure education for youths have made some progress but also face impediments. The Safe Schools Declaration in 2015 was adopted by the Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack, in part in response to increasing violence toward girls in school during times of conflict, and was signed by 116 countries including the DRC. The coalition’s mission is twofold: increasing reporting and monitoring of violence against education and reducing attacks on education including the use of schools by armed groups and the targeting of girls. The coalition provides services to girls after their schools have been attacked and provides spaces for continued education. Though commendable in its approach, programs such as this often fall short of fully implementing the Safe Schools Declaration due to the severity of the violence and minimal accessibility to affected groups.

UNSC 2601

The United Nations has served as a leader in the dialogue on violence in education. In 2021, the U.N. responded to increased violence by Boko Haram and ISIS- and al Qaeda-linked groups by passing Resolution 2601, condemning attacks on education. This resolution was supported by 99 states and included an implementation plan to increase continuous education in conflict-affected areas. A key challenge to this resolution is implementation; much of the violence is conducted by nonstate actors, restricting international organizations’ ability to respond. Furthermore, this resolution appears to have had an inverse effect: After it passed, there was an increase in school attacks in Cameroon, Mali, and the DRC, suggesting that the current international approach is limited in its ability to support youth populations and protect educational gains. The international community, while essential to wars on education, must rethink the way it approaches violence and work toward increasing dialogue and providing spaces for education to thrive as opposed to top-down approaches that minimize the effectiveness of local actors. An approach that has had limited reach but high impact is community dialogues.

Community Dialogues in Mali

Conflict in Mali has raged for decades with minimal progress toward peace. These conflicts have led to increased instability within the education system, which has had a growing impact on civilians. Between 2018 and 2019, violent extremist groups closed and destroyed over 400 schools in the Mopti region. In response, in 2020 a group of political and religious leaders led a series of negotiations with militant groups between 2020 and 2022 with the goal of reopening schools and moving militant activity away from educational centers. By the end of 2022, the religious and political leaders saw the reopening of the only two operational schools in Mopti. In addition to negotiating for the opening of two schools, local leaders convinced the violent extremist groups to move their bases away from educational facilities and to refrain from planting improvised explosive devices near the schools and major transportation routes to and from the schools. Through these negotiations, schools have reopened. Since the schools reopened in 2022, the community has seen a return of markets, basic government administration, and activities that were once banned by the violent extremist groups.

Such negotiations are done largely by prominent families and local religious leaders through intermediaries within the violent extremist group. Villages are also known to organize listening sessions, like town halls, to work toward a compromise with militant groups that reinstitutes basic services such as education. This process is largely done with the intent of finding a middle ground. In the specific case of Mali, the militant groups were not inherently political but instead participated in the talks to avoid isolating themselves from the community and potentially alienating those that they wished to empower. This was used by local tribal leaders as a strategic advantage to promote reopening schools, which in turn aided in restarting the economy in Mopti. As one of the main grievances of militant groups is economic exclusion, jumpstarting the economy in the region was seen as mutually beneficial, and thus a deal was brokered to allow schools to reopen.

Policy Recommendations

Historically speaking, European countries have taken the lead in combating insurgent threats and violence in the Sahel and Central Africa. However, in the last three years, anti-Western sentiment and European and U.N. withdrawals from Africa have created a vacuum for militant and malign actors to thrive, making it increasingly difficult for Europeans to respond to these crises. Moreover, as Africa’s instability continues to grow, this represents an opportunity for strategic competition with Russia and China, making it ever more important that the U.S., with its international partners, responds to the violence against education.

- The U.S. and its partners should coordinate more closely with community and advocacy groups. At the local level, regional and international non-governmental organizations should focus on providing temporary learning spaces in refugee and IDP camps to avoid long periods of educational gaps for those who are displaced. Additionally, special priority should be given to girls to provide them with access to education and safe spaces when educational opportunities are limited as a mechanism to limit opportunities for gender-based violence.

- The international community should work with governments to create implementation plans that are inclusive and accessible. The international efforts to secure access to education do not take much action on several key principles, such as restricting schools for military use during conflict and safeguarding education in war-torn areas. The lack of effective implementation on the ground is limiting the international community’s effectiveness in responding to violence against schools, but working with governments in the region can make those responses more fruitful.

- Supporting local NGOs that are already working to safeguard schools is essential to building out any kind of implementation of international orders. For example, in Burkina Faso, organizations such as Education Cannot Wait have a Multi-Year Resilience Program that supports marginalized students’ access to education by paying school fees, providing remedial classes, and supporting teachers; this inherently keeps schools open and provides much-needed access in war-torn areas.

- At the local level, prioritizing the reopening of schools and increasing operational capacity for schools in blockaded areas in Mali and Burkina Faso is essential. A key to this will be relying on local leaders to broker peace with violent extremist groups. In the short term, governments should allow local leaders to drive the conversation with violent extremist groups in terms of brokering peace and stability around education. As seen in Mali, this is not an easy feat but an essential first step in reopening and securing the operation of schools in war-torn areas.

- Prioritizing support for girls to increase school enrollment rates and break down gendered barriers to education access is crucial. Financial support from NGOs should focus on prioritizing girls’ education by covering school fees and by providing conditional cash transfers to families so that girls can attend schools. Additionally, financial resources should also be focused on providing psychological services to students who are afraid to return because of violence. One strategy is to train more teachers in School in an Emergency Curriculum which trains both students and teachers in how to protect themselves in instances of attacks while providing psychological care for victims of school attacks.

Education stands at the forefront of the prevention of increasing violent extremist activity. It is imperative that the international community consider both localized and international approaches that prioritize safe education and training for children and young adults. Without proper education, adolescents are left with minimal resources and opportunities for growth and development, leaving them to search for other opportunities for community and employment – one of the main reasons individuals join violent extremist groups. Supporting education will in turn support African countries that are plagued with fragility by building up a skilled and educated workforce that can establish stable societies. This, however, is only possible if young adults and children have a safe and secure environment to attend school consistently, making education the backbone of state stability.

Jessica Malobisky is a graduate student pursuing a master’s in International Development Studies at The George Washington University. Her interests are in the impact of conflict on civilians, including the need for long-term solutions to humanitarian aid and forced displacement throughout sub-Saharan Africa and the MENA region. While obtaining her bachelor’s degree at The George Washington University, Malobisky interned with Multifaith Alliance as a Policy and Advocacy Intern. In this role, she studied the conflict in Syria, conducting research on the illicit captagon trade and cross-border interdictions in Jordan and Lebanon. She also studied the migration of Syrian refugees throughout the region.

Riley Moeder is a Senior Analyst for the Special Initiatives program at the New Lines Institute, focusing her research on North Africa and Strategic Rivalries. Prior to joining the institute, Riley was a program assistant for the United States Institute of Peace in the Middle East and North Africa department. She previously worked at American Enterprises Institute in the Critical Threats Department, researching non-state actors in the Sahel. She attended Lewis & Clark College, where she received her B.A in International Relations. She also studied in Strasbourg, France, where she researched international human rights law and refugee policy.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of the New Lines Institute.