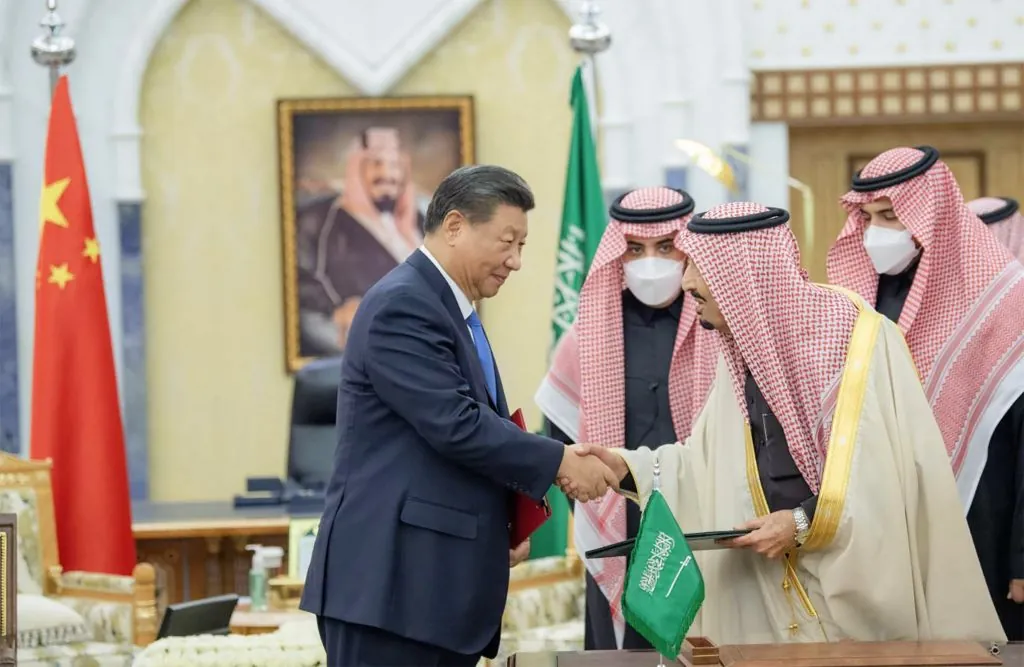

A series of transformative events has reshaped the dynamics of the Middle East in the past three decades. The withdrawal of American forces from Iraq and Afghanistan, coupled with shifts in Saudi Arabian crude oil trade and the rising economic footprint of China, paved the way for a change of perceptions vis-à-vis power relations in the Middle East. Chinese President Xi Jinping’s participation in the 2022 Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) summit and the Gulf nations’ recent interest in joining BRICS (the bloc of emerging economies that currently includes Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) and its New Development Bank created much hype around China’s presence worldwide, particularly in the Middle East. For now, Chinese leaders are sticking to the discourse of economic cooperation and deepening diplomatic relations between China and the Gulf nations. However, the increasing contrasts between China’s cautious official communication and its aggressive approach in this evolving “multipolar” panorama warrant a closer look. Despite the country’s guarded optimism, China’s engagement in the Middle East faces significant limitations.

China’s Middle East engagement reveals a dynamic influenced chiefly by economic factors. As the world’s largest oil importer, China has fostered deepening ties with Gulf states through increased trade. Its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) investments underscore its commitment to economic collaboration, investments, and commerce in the region and are particularly shown in infrastructure projects aiming to bolster connectivity. Additionally, there is a digital dimension to the engagement, including 5G deals and the development of cyber strategies. Yet limitations to China’s influence in the Middle East surface, particularly in the realm of security, as China’s noninterference policy restricts active involvement except for a couple of joint military drills. Economically, challenges loom for the country, including the current property crisis and mounting local debt, showing that even the strongest way for it to engage in the Middle East region may be subject to limitations. Geopolitically, concerns about Indo-Pacific maritime disputes and South China Sea island militarization may orient China toward a more regional focus.

Overall, despite the extensive constraints on China’s engagement in the Middle East, there remains a constant risk that certain critical areas may be shaped through economic relationships, such as technology investments and the construction of critical infrastructure facilities, and spill over into regional security and defense areas. Accordingly, the U.S. response should encompass deepening economic cooperation with Middle Eastern economies, and should also monitor commercial agreements under the BRI, scrutinize the future objectives of China’s BRI investments and delve into the linkages between investment areas and strategic purposes tied to them, fortify alliances with Asian partners against China’s growing regional assertiveness, and safeguard pivotal sectors like the defense industry.

Economic Cooperation and Diplomacy as Conduits

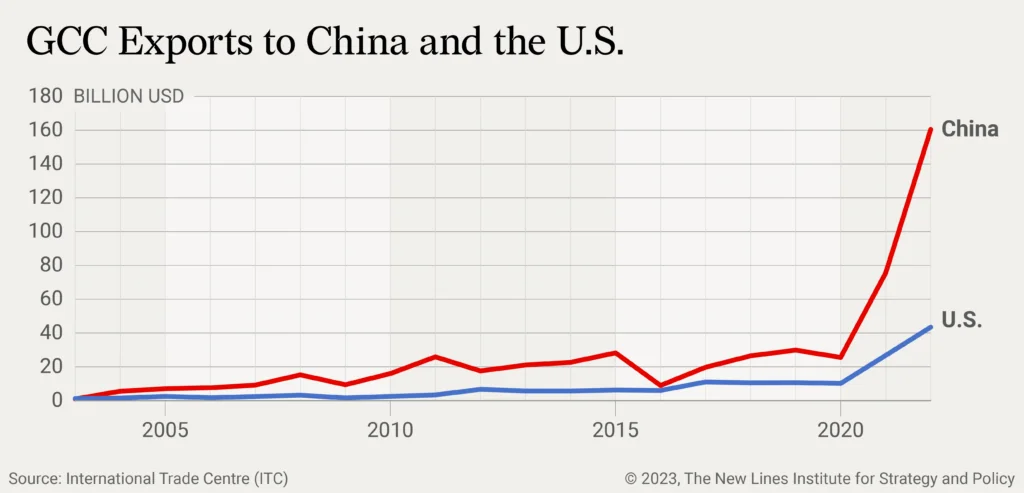

China’s engagement in the Middle East is primarily structured around economic cooperation and trade. Over the years, the increasing trade in oil has positioned China as the largest importer of petroleum from the GCC. This economic-oriented engagement has gained momentum as a result of business conferences, free trade negotiations, and bilateral trade deals. China, with its export-driven growth model, has consistently sought new markets, and the Gulf nations’ interest in diversifying their trade partners overlapped with this search. In June 2023, for instance, during the 10th Arab-China Business Conference in Riyadh, Chinese companies signed more than 30 agreements, collectively worth $10 billion, with Saudi entities as well as those from other Gulf nations. This diversification of investments encompasses sectors including stock markets, technology, and energy.

China’s BRI, a mega infrastructure project chain that has been ongoing since 2013, plays a pivotal role in enhancing China’s capacity to engage with different geographies, primarily driven by economic considerations. In the context of China’s relations with the Middle East, the BRI’s significance is particularly noteworthy, especially when examining the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). CPEC showcases the interplay between economic and geopolitical considerations and shows how strategic opportunities and limitations intertwine. This endeavor could help China circumvent the Strait of Malacca, a maritime gateway connecting the Andaman Sea and the South China Sea, where neighboring states have maritime border disputes that could escalate.

Even with no future escalation in the South China Sea, CPEC offers a significantly shorter route to Pakistan for Beijing, which strives to establish land routes, not just maritime ones. This connection is ideal to cut time and cost for trade. The Gwadar Port, a critical component of the BRI, gives China direct access to the Middle East. The Pakistani government previously requested the transfer of much of the land controlled by the Pakistani army to the Gwadar Port Authority. For security reasons, military acquisition of lands in the region is subject to approval by Chinese contractors. While Chinese media consistently downplay any claims that there will be a Chinese military base on-site in the Gwadar Port, considering the proximity of the port to the Arabian Sea and the Persian Gulf, the possibility of the People’s Liberation Army Navy establishing a naval base in the region is not out of the question.

However, CPEC faces a bumpy road ahead, not only geopolitically but also in light of China’s economic situation, which might be one of its most significant tests this year. The real estate crisis centered around the Chinese property giant Evergrande could lead to financial troubles, potentially exacerbating domestic unrest. Data from a recent undergraduate thesis study suggested that the collapse of Evergrande could have a more negative impact on BRI countries than non-BRI countries; in the face of these challenges, BRI projects may receive less interest from host countries in the coming years. CPEC, touted as the most expensive and prominent component of this mega investment initiative, will likely fail due to China’s domestic economic issues and ongoing regional problems, such as the increasing attacks on Chinese nationals working in Gwadar and the complications created by Pakistan’s military institution. This potential flop, in turn, will impact China’s image in the Middle East.

China’s transactional relationships with regional countries are considered enabling factors, but the emergence of constraints imposed by domestic economic problems pushes the Chinese leadership to reassess its foreign investments. That said, China’s economic-based relationships do not adhere to a monolithic pattern of ups and downs.

China’s Middle East involvement, primarily steered by economic interactions, compels it to carry out independent initiatives such as bolstering multilateral trade agreements with Gulf partners and accelerating the negotiations for a free trade agreement. This necessity arises from the inherent limitations of the existing groups and coalitions to effectively advance China’s objectives. The recent invitation of Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Iran (among others) to the BRICS summit in Johannesburg, with their prospective full membership in 2024, is a prime example. The motivation driving Saudis and Emiratis is, to some extent, to recalibrate their relations with Washington by using BRICS membership as a balancing tool. Concurrently, Iran’s long-standing ties with China and Russia have now been formalized through this membership.

Furthermore, the prevailing frostiness and intensifying competition between China and India accentuate the need for China to independently strengthen its bonds with new members, thereby bolstering its role as a prominent influencer within the BRICS framework. China is employing a similar strategy with the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, where Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Qatar are dialogue partners. This configuration significantly constrains the organization’s operational purview, resulting in a limited potential for forming a cohesive regional bloc.

Diplomatic Overtures

In addition to fostering economic cooperation and strengthening trade ties, Beijing employs strategic communications that emphasize peace, stability, mutually beneficial outcomes, civilizational friendship, and solidarity. Such rhetorical exercises are part of China’s nation-branding that manifests itself with speeches and headlines on state-run media channels and newspapers.

At times, this rhetorical approach becomes intertwined with diplomatic actions; the Saudi-Iran normalization is a case in point. Beijing’s mediation was heavily mediatized, exaggerating the perception of China as a mighty and skillful diplomatic actor. Instead of analyzing the rationale behind the reconciliation between Saudi Arabia and Iran, media narratives boosted China’s perception-management efforts. This overstatement has come at the expense of countries like Iraq and Oman, whose governments did much of the heavy lifting while China reaped the benefits in the media sphere.

Soured Regional Relations

China’s growing interest in the Middle East and its potential to establish itself in the region as an alternative power to the U.S. face limitations. Among these are the challenges China faces with countries in its vicinity, such as maritime disputes with Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Japan, and border disputes with India. These constraints represent a resource allocation dilemma for China; territorial disputes in its own region and militarization in the seas limit China’s operational capabilities (e.g., joint military operation capabilities) and its ability to form alliance blocs in the region against the U.S.

The ongoing disputes over the Paracel and Spratly Islands in the South China Sea remain unresolved, and China continues to pursue aggressive stances there. Recent satellite imagery captured the construction of an airstrip on Triton Island, part of this archipelago. Increased Chinese military presence on the islands has led to escalation, as Vietnam plans to accelerate military construction on Pearson Reef and Pigeon Reef as a countermeasure. The long-standing disagreement between Japan and China over the Senkaku Islands (Diaoyu in China) is another thorny issue, as is the dispute with India over the Himalayan borders.

This year’s NATO summit in Vilnius introduced China as a topic of discussion, highlighting the challenges Beijing poses to the alliance’s interests. The participation of the AP4 – comprising South Korea, Japan, New Zealand, and Australia – as strategic allies in the Asia-Pacific region has likely steered China’s attention. Furthermore, at the Camp David summit, U.S. President Joe Biden conveyed messages of economic and security cooperation, including missile intelligence-sharing systems and joint missile interception drills, with South Korea and Japan, reiterating a collective response against China’s unilateral actions.

As the U.S. enhances its relations with Asian partners, China uses such dynamics to justify its military presence on the disputed islands in the South China Sea and to resume its anti-American narrative that accuses the U.S. of militarizing the region. While Japan and South Korea have long-standing disagreements, the nations are likely to enhance their cooperation to address the bellicose Chinese approach. On the other hand, save for North Korea, it is more difficult for Beijing to establish alliances in the region. Thus, territorial disputes remain a significant disadvantage for Beijing.

The Security Dimension

China’s conventional foreign policy stance includes the principle of noninterference, which is also one of the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence outlined in its constitution. China defines itself as a neutral actor, even though the country’s actions have not always aligned with these noninterventionist ideals. For instance, during the U.N. Security Council Resolution 678 voting in 1990, which paved the way for military intervention in Iraq, China abstained from using veto power to avoid alienating the U.S. In response, the U.S. lifted World Bank loan sanctions after the Tiananmen Square crisis and accepted the invitation of China’s foreign minister at the time, Qian Qichen, to the White House. This shows that even back then, China used its identity as a neutral actor in conjunction with transactional diplomatic moves to ensure it won favors from Washington.

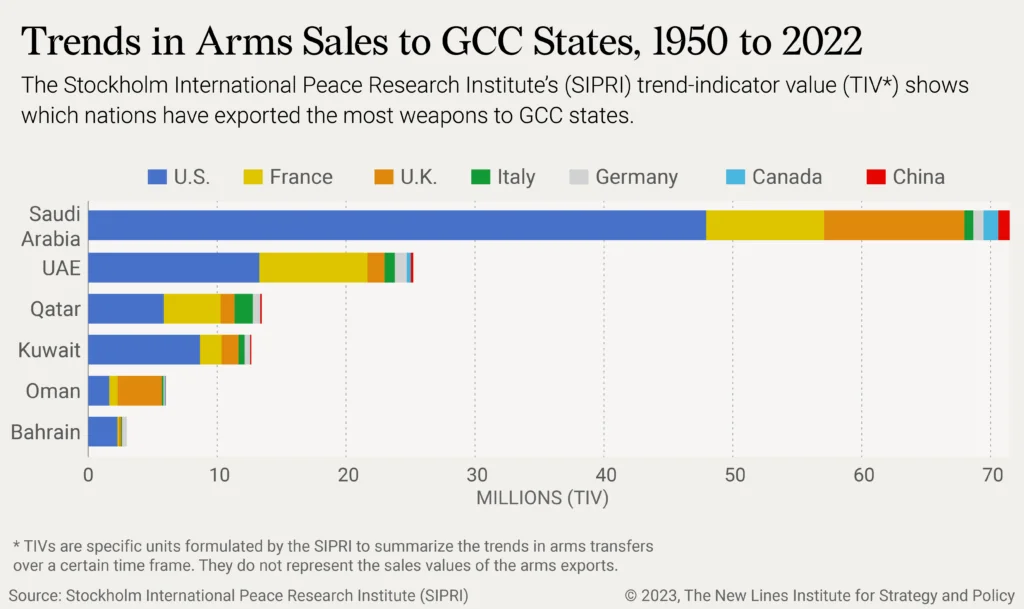

Regarding security, China conducts joint military maritime and air drills with countries like Saudi Arabia and the UAE, such as Falcon Shield 2023 with the Emirati Air Force. From a Chinese perspective, the exercises are primarily held to modernize the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) operational capacities. From a Gulf standpoint, they serve as a message to the Biden administration that these nations have other options on the table, though it is worth noting that most of the Middle East’s military doctrine, training, and equipment are sourced from the United States (including 78% of Saudi Arabia’s arms).

The reality is that the PLA is far from asserting its power beyond its vicinity. The Chinese army has long been grappling with rampant corruption in the higher echelons of military command and a lack of joint operational capacity. The PLA also has not had combat experience since the Sino-Vietnamese War in 1979. These challenges seriously curtail China’s ability to emerge as a viable security alternative to the United States, or at least to engage deeply in the region’s security architecture. It is not clear, however, that that is China’s intention in the Middle East. Given the country’s nonconfrontational and noninterventionist approach, engaging in such a costly endeavor is unlikely to be a desirable option for China. Given the PLA’s existing deficiencies, a geopolitical shift detrimental to Washington remains a distant possibility.

Security considerations can be seen as limitations rather than enabling factors in this context, and two examples illustrate this point. First is the cancellation of two Israel-China deals – the 2000 PHALCON airborne early warning system and the 2004 IAI HARPY drone – due to pressure from Washington. The termination of these deals highlights how China’s engagement in the region can be significantly constrained, especially in instances involving the potential transfer of American defense technology.

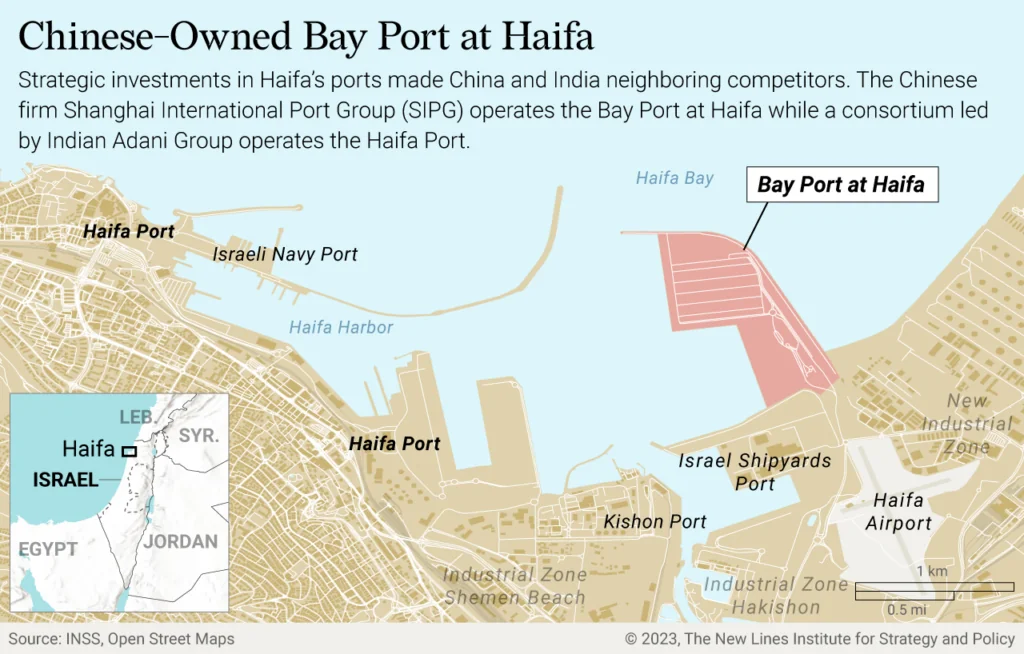

Another example pertains to the recent awarding of the Haifa Port contract to the Indian Adani Group last summer within the framework of the I2U2 Group, a collaboration between India, Israel, the UAE, and the U.S. The strategic proximity of the port to the Israeli Navy and the U.S. Sixth Fleet, as well as the 25-year lease granted in 2015, had already caused serious concerns for Washington. In bilateral discussions, the U.S. conveyed to Israel that its economic relations with China, especially concerning infrastructure investments in strategic locations, could impact U.S.-Israel security ties. These cases illustrate that the U.S. prefers not to see China within the regional security architecture and is uncomfortable with the potential shift of economic relations toward noneconomic ones.

The recent developments in the ongoing Israel-Palestine conflict showcase the nuanced dynamics within the broader U.S.-China rivalry unfolding in the Middle East. There is a distinct dichotomy between China’s measured and pragmatic approach and the United States’ more assertive stance. China’s strategic calculus involves engaging with both parties, maintaining equilibrium, advocating for a two-state resolution, and articulating its position as per the U.N.’s diplomatic lexicon. Notably, China refrains from adopting an overtly adversarial posture toward Israel, recognizing its indispensable economic ties, particularly in the lucrative defense, high-tech, and start-up markets. In response to the U.S. deployment of aircraft carriers, the USS Gerald R. Ford and USS Dwight D. Eisenhower, China dispatched six warships to the Mediterranean. Though framed by Chinese media as a routine escort mission and a diplomatically calibrated “friendly” visit, this move reveals China’s modus operandi. Beijing is reluctant to involve itself in the conflicts or interventions in the Middle East – a marked departure from the more interventionist approach adopted by the United States.

The U.S. Response

Given China’s growing presence in the Middle East, the United States’ potential road map should prioritize China’s enabling factors and limitations as a combined foreign policy strategy.

- American decision-makers should prioritize their assessment of China’s economic engagements in the region. The duration of contracts, particularly in key infrastructure investments, should be scrutinized for potential long-term security risks, and partners should be made aware of these concerns. While reducing China’s influence in the Middle East’s energy market may be challenging, the geopolitical consequences of BRI projects should be carefully assessed. Vigilance is necessary regarding the potential of the Gwadar Port investment to lead to a People’s Liberation Army Navy presence near the Gulf. Furthermore, China’s involvement at Israel’s Haifa Port should be reevaluated not only economically but also from a geopolitical perspective to anticipate potential implications. U.S. administrations may have been aware of the downsides of China’s strategic economic investments, but instead of immediately countering China’s moves, they analyzed the investments to understand China’s playbook. If this is the case, Washington can dictate the tempo of Chinese moves in the future without provoking an escalation through hasty reactions.

- The main impediments to China continuing its engagement in the Middle East are the complex issues within its sphere of influence. Starting with NATO, Washington’s planned strategies for China, such as deterrence or containment, focus on increasing regional partnerships. In response to the militarization of the South China Sea, missile intelligence-sharing systems with partners should be empowered, and military drills should be conducted to enhance the region’s joint military action capabilities. Partnerships like AUKUS, QUAD, AP4, and I2U2 should also be expanded.

- It is important to highlight that security is a critical boundary that should not be trespassed, particularly in arms sales, security cooperation, cyber technology, infrastructure agreements proximate to strategic locales, and data technologies. The imperative of safeguarding rights and freedoms, perennially resonant within U.S. foreign policy, must not hamper strategic interests. It is essential to closely monitor joint military exercises between Middle Eastern countries and China’s PLA, which enhances operational capabilities. The U.S. should prioritize a cooperative spirit in its regional strategies and pave the way for further collaboration with security strategies and operational capacities. This strategic recalibration preempts the Middle Eastern nations’ inclination to diversify their trade partners, forestalling any spillover into defense and security affairs.

- The Middle East has been considerably weakened by the U.S. policies since 2001. As such, Washington cannot suffer any further strategic miscalculations. Two key foreign policy mistakes made during the Bush and Obama administrations should be highlighted. First, the failure of the Iraq invasion to achieve the intended democratic transformation and the subsequent rise of terrorist groups stemmed from a disconnect with the social fabric of the target countries. Instead, a more suitable approach for the U.S. would have been offshore balancing, involving cooperation with the U.N. for regional security. Secondly, the Obama administration’s Syrian policy initially aimed for President Bashar al-Assad’s removal and a democratic transition. However, as the Syrian conflict extended, U-turns in policy occurred. As former Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Middle East Policy Andrew Exum’s testimony in 2019 revealed, Washington held secret talks with Moscow and shared intelligence to mitigate the risk of heightened instability resulting from a sudden collapse of the regime in 2016.

Considering this, the United States should align actions with local realities and strategic priorities to prevent politicization, selectivity, and double standards and to combine value systems with strategic interests. The U.S. must do less compartmentalization regarding its regional strategies and recognize its interconnectedness to remain a force in the region.

Burak Elmali is a Researcher at TRT World Research Centre in Istanbul. He holds an MA degree in Political Science and International Relations from Boğaziçi University. His research areas include Turkish foreign policy and great power politics with a special focus on U.S.-China relations and their manifestations in the Gulf. He has contributed many articles to various media outlets. He tweets at @Burak_elmalii

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of the New Lines Institute.