Listen to article

The modern Indian state was carved out of the subcontinent in 1947, and it has been trying to make its presence felt within the global community ever since. India maintained an overtly nonaligned stance during the Cold War, and it still aims to preserve its relations with Russia, even as it comes closer to the United States. For its part, the U.S. began to pursue a closer relationship with India during the presidency of Bill Clinton. This was in part to counterbalance China’s influence in Asia and because the U.S. increasingly viewed India, the largest democracy in the world, as a natural ally.

However, the steady rise of Hindu nationalism in India is fast turning this heterogenous country into an autocracy. Ignoring India’s descent into ethno-majoritarian rule has adverse implications throughout the region. Indeed, the persecution of religious minorities in India is causing evident friction with neighboring Muslim states. India’s growing culture of intolerance is also tarnishing its democratic credentials, which undermines American attempts to use enhanced economic and security cooperation with New Delhi as a bulwark against China’s growing influence in South Asia. For all these reasons, it is imperative that U.S. policymakers pay more attention to helping reverse the rise of Hindutva, a far-right ideology that is eroding human security in India, exacerbating friction in an already tense region, and making New Delhi a much more difficult partner to work with.

As Hindutva Rises, Democracy Strains

With a population of over 1.2 billion, India has become the world’s second most populous country. Over the past decade or so, it has achieved significant economic growth. Indeed, some of the more optimistic forecasts expect India to become the third-largest economy in the world by the mid-2030s.

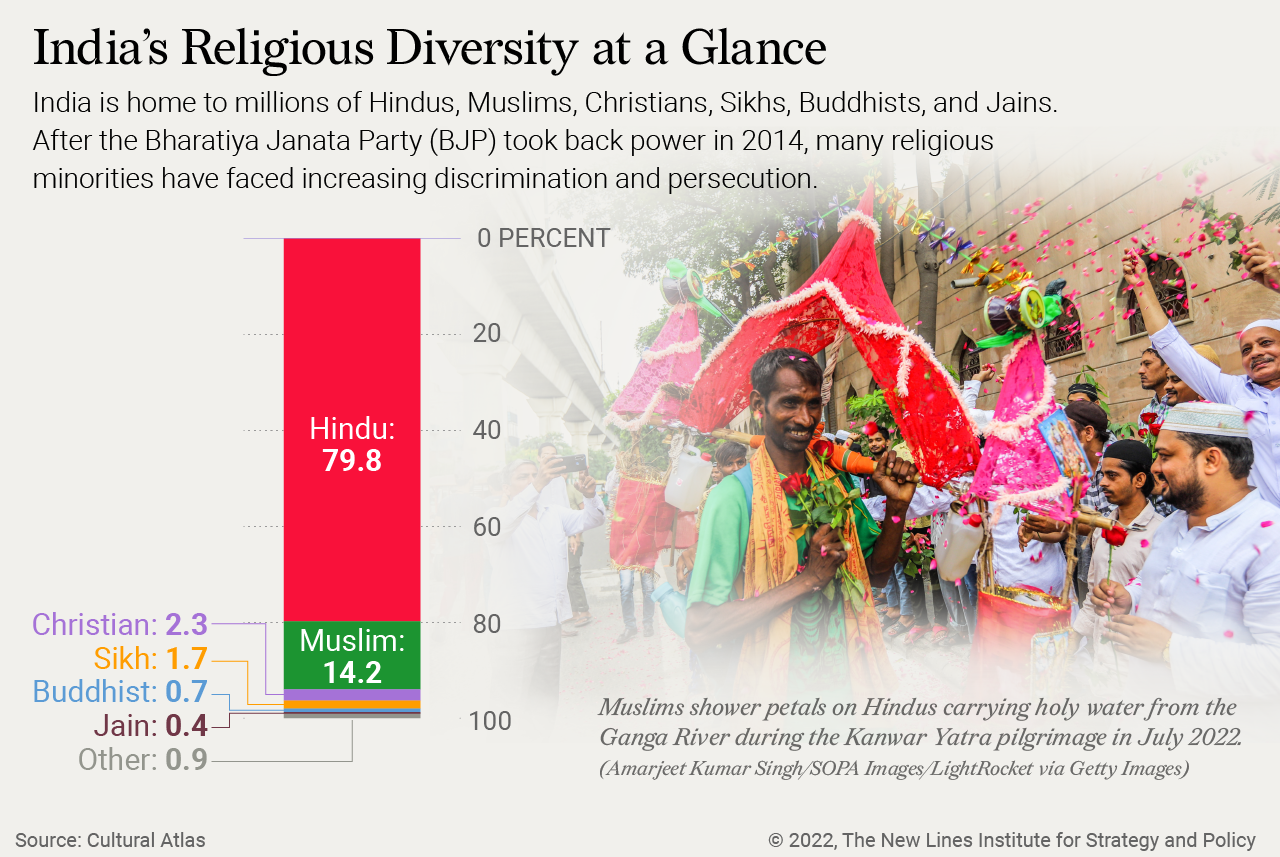

India is also a religiously diverse country. While Hindus comprise the majority of India’s population (79.8%), there is a significant Muslim minority population (14.2%). Christians and Sikhs account for 2.3% and 1.7% of the Indian population respectively, with Buddhists, Jains and others making up the remaining 2%. Being the largest democracy in the world, India is often viewed as a role model for other heterogeneous countries trying to transition to democracy. Yet India’s own democracy remains fraught. The communal tensions that continue to undermine it have their roots in the traumatic process of partition from 75 years ago.

The hastily administered bifurcation of the Indian subcontinent by its British colonizers was accompanied by the forced displacement of Muslims in Hindu-dominated areas to what had become Pakistan. Similarly, most Hindus settled in Muslim-majority regions were displaced to the newly created state of India. This mass migration was marred by rampant bloodshed, leading to between 1 million and 2 million deaths. While many Muslims shifted to Pakistan, a significant proportion of them stayed in India. Despite efforts made by the newly created Indian state to protect its minorities, Indian Muslims, along with other religious and ethnic minorities, have experienced recurrent discrimination and violence.

The communal rifts in India have only intensified over time, and the increased persecution of minorities in the country has coincided with the rise of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). Formed in 1980, the BJP shot to prominence when it managed to create a coalition government after the 1998 general elections. The BJP was defeated by the Indian National Congress in the 2004 elections, but it remained the leading opposition party for the next decade. It returned to power in 2014 under the leadership of Narendra Modi, who is currently serving his second term as India’s prime minister.

India seems to have shaken off the dynastic rule of Congress, the party that spearheaded the struggle for independence and held a lock on power for decades. Now, though, the BJP and its Hindutva ideology are increasingly taking over the country’s political imagination. The party itself is the political wing of Sangh Parivar, a grouping of Hindu extremist organizations that considers non-Hindus as foreign to India and aggressively promotes the “Hinduization” of Indian culture. Besides the BJP, a range of other Hindu-nationalist groups operate in the country, including the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, the Vishva Hindu Parishad, and the Shiv Sena. Such groups often work together in their effort to “saffronize” India through violence, intimidation, and the harassment of religious minorities.

The ruling BJP is blamed for deliberately widening the communal rifts that already existed in India to advance its own political ambitions. The BJP’s promotion of Hindu nationalism has entrenched discrimination against India’s religious minorities, including Muslims, Sikhs, and Christians. Following its re-election in May 2019, the party has stepped up efforts to suppress the media and civil society. Further, its ultranationalism has far-reaching political, socio-economic, and cultural consequences, both in the country and throughout the broader region.

Modi’s Ad-hoc Autocratic Approaches

The Modi government has embraced neoliberal policies that have enabled India to achieve economic growth. However, while India has seen a significant reduction in absolute poverty under these policies, the benefits of economic growth remain lopsided and patchy, and they seem to be worsening India’s already glaring poverty. The increasingly hegemonic manner of resource extraction to fuel growth has caused significant resentment. It has fueled insurgencies across the Naxalite-Maoist corridor, which currently stretches across a dozen states, and in the northeast of the country, where nearly 40 militant groups are active across six states. Worse still, the government’s decision in 2019 to revoke the constitutionally enshrined special status of Jammu and Kashmir has not only worsened human security in this restive region but has also increased tensions with neighboring Pakistan, which disputes Kashmir’s accession to India during the partition of the subcontinent. China also claims a smaller portion of these India-held Himalayan territories, and India’s revocation of special status provoked a skirmish between India and China in 2020. That marked the first clash between the armies of the two states since the Sino-Indian war in 1962.

The Modi government’s uncompromising attitude is not confined to dealing with separatist aspirations and insurgencies. A similarly autocratic approach is taken to address other pressing public policy challenges. During his first term in office, Modi abruptly decided that the two largest Indian currency notes (the 500-rupee and 1000-rupee notes), which together made up 86% of the currency in circulation, would no longer be valid and had to be exchanged for new notes. This dramatic move was meant to target tax evaders, but it also had a detrimental impact on poor people, who do not trust banks and prefer instead to keep their meager savings in cash. Many people were unable to trade their old notes for newly issued currency notes in time.

Similarly, the BJP government’s high-handed implementation of COVID-19 lockdowns left multitudes of migrant workers stranded far from home in major cities across the country. The origins of the pandemic were also twisted into an Islamophobic conspiracy theory, with BJP leaders accusing Muslims of purposefully spreading the virus in an effort to carry out a “CoronaJihad.”

Finally, the Modi government’s sudden decision to further liberalize agricultural production triggered the largest wave of protests in the country’s history, led by the Sikhs in Punjab and Haryana. The demonstrations went on for months, eventually compelling the government to backtrack on its decision to withdraw minimum price guarantees for major crops.

These instances of ad hoc decision making have characterized BJP rule as much as the pervasive presence of major economic problems, such as inflation and unemployment, that are particularly painful for the poor. Despite all of this, the Modi government has used populist rhetoric and ethno-nationalism with evident success to win consecutive terms in office. The ruling government’s brand of Hindu nationalism, however, has significantly strained India’s socio-economic fabric and has eroded trust in the institutions of the state.

Turning Justice on its Head

The vehement policing of caste, class, and religion is corroding tolerance throughout society, and violence is readily used to punish any transgression. Discrimination against marginalized segments of Indian society has increased. Even state institutions such as the judiciary and the police, especially at the lower levels, have adopted a majoritarian undertone. For instance, attacks by Hindu extremist groups against Muslims and Christians are often followed by arrests of members of the very religious minorities who were attacked. Those detained are accused of attempting to convert Hindus to other faiths. The perpetrators of violence go free.

The panic over the phenomenon of so-called “love jihad” is illustrative. According to Hindu groups, “love jihad” is a conscientious ploy by Muslim men to entrap and marry Hindu women to convert them to Islam. This formulation evokes anxieties about the erosion of socio-cultural identities, and it pushes stereotypes about Muslims being extremists and terrorists. Hindu vigilante groups frame their activities as “rescue operations” trying to counter “love jihad.” Hindu nationalist groups have used threats and force to separate interfaith couples. Their activities have also been supported by right-wing lawyers who help identify and share information about inter-religious court marriages between Muslim men and Hindu women. While levelling false accusations of rape, kidnapping, or brainwashing against Muslim men, Hindu extremists use their political patronage and strong links with the police to take action against “love jihad.”

This false framing has made its way into politics, as well. During the 2017 state election campaign in Uttar Pradesh, the BJP repeatedly referenced the problem of “love jihad,” and following their electoral success, the police were instructed to form “anti-Romeo squads” to contend with it. Several states have also seen violent “beef lynchings” of Muslims and Dalits (former untouchables) by cow-protection vigilante groups, and Karnataka has allowed education institutes to ban wearing the hijab in classrooms.

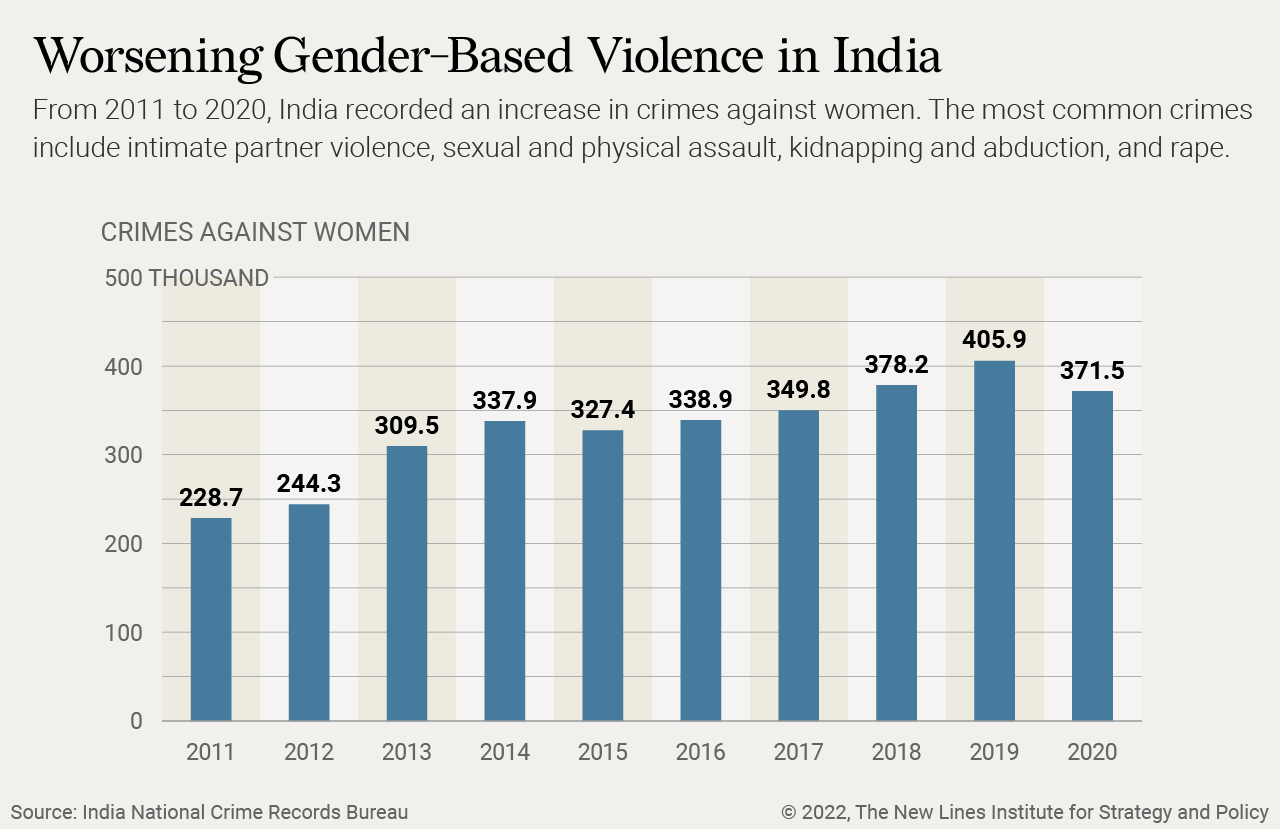

The lingering problem of violence against women across India has also taken on a new dimension under the BJP. The party has been criticized for its incendiary rhetoric encouraging sexual violence against Muslim women and girls. Muslim women, particularly those seen as critical of BJP rule, are also met with an avalanche of online sexual violence by the Hindu right.

Many cases of violence, against ethnic and religious minorities as well as against women, remain unreported because the police are not willing to file cases against Hindu extremist groups. In cases where the police do try to challenge these groups, retaliation against them can be aggressive, with police officers reportedly suffering serious injuries. Police reluctance to address political or communal violence also stems from the increasing politicization and communalization of the police force itself. Analysis of data on police action following different instances of communal violence indicates that religious minorities are not only disproportionately the victims of such violence but also further targeted by law enforcement agencies during action taken to quell the unrest. These factors contribute to the impunity enjoyed by Hindu extremist groups across India.

Many senior BJP leaders openly promote Hindu supremacy and ultranationalism, and they publicly use discriminatory language about religious minorities. Most recently, a senior BJP spokesperson created an uproar by making provocative statements about the Prophet Muhammad during a televised debate in early June. Another BJP spokesperson then defended these statements on social media. The party suspended both these officials, but this seemingly stern action was only taken after several Muslim-majority countries lodged protests and called for a boycott of Indian goods. The response to protests by Muslims within India itself, on the other hand, has been quite heavy-handed.

The fact that the BJP won four significant state elections earlier this year shows the steady influence Hindu nationalists continue to enjoy. Uttar Pradesh, the most populous Indian state, saw former Hindu priest Yogi Adityanath, who is well known for his anti-Muslim stances, win another term as chief minister. In fact, Adityanath is now considered a promising candidate for prime minister in the next general elections, which are scheduled for 2024. Were Adityanath to become Modi’s successor, India could complete its transition from a flawed and fragile democracy into a theocratic state. That possibility evokes tremendous discomfort among the Indian intelligentsia, and a theocratic India would be a much more difficult country to collaborate with for the international community – including the United States.

How the U.S. Can Enhance Human Security in India

The U.S. has many reasons to preserve and enhance its bilateral relationship with India. Its burgeoning population offers a lucrative market for U.S. business, and India is viewed as a strategic partner that is key to helping contain and counter Chinese influence in South Asia. Yet India’s increasing authoritarianism is a growing source of concern – a factor that could stifle India’s potential to become the mutually beneficial partner that the U.S. envisions.

In its 2021 Human Rights Report on India, the U.S. State Department noted several significant problems plaguing the country. These include arbitrary detentions and arrests, extrajudicial killings, pervasive violence against religious and other minorities, and the muzzling of critical voices. However, concern over India’s human rights violations has not yet changed the upward trajectory of U.S.-Indian relations.

In fact, the U.S. has worked to accommodate the reality of a rising BJP. Narendra Modi used to be persona non grata in the United States, was barred from entry to the country for his alleged role in the Gujarat massacre of Muslims in 2002, while he was that state’s chief minister. This changed once he was elected prime minister. Modi received the red-carpet treatment not only in the U.S. but also in much of Europe. While a government-ordered special investigation cleared Modi of culpability in the Gujarat riots, a petition was filed to challenge this decision. The Indian Supreme Court in late June this year gave a long-awaited decision on this plea, dismissing the challenge to Modi’s exoneration. Following that verdict, a prominent activist who was a co-petitioner seeking a retrial of the Gujarat riots was arrested, accused of involvement in an alleged conspiracy to send innocent people to jail.

In trying to woo India into a strategic partnership, the U.S. may have inadvertently boosted the legitimacy of Modi’s BJP. The prevailing hyper-nationalism in India may be a source of discomfort for U.S. policymakers, but their willingness to overlook these violations and to continue working with the Modi government to build stronger bilateral ties bolsters his image as a strongman who is turning India into a global power.

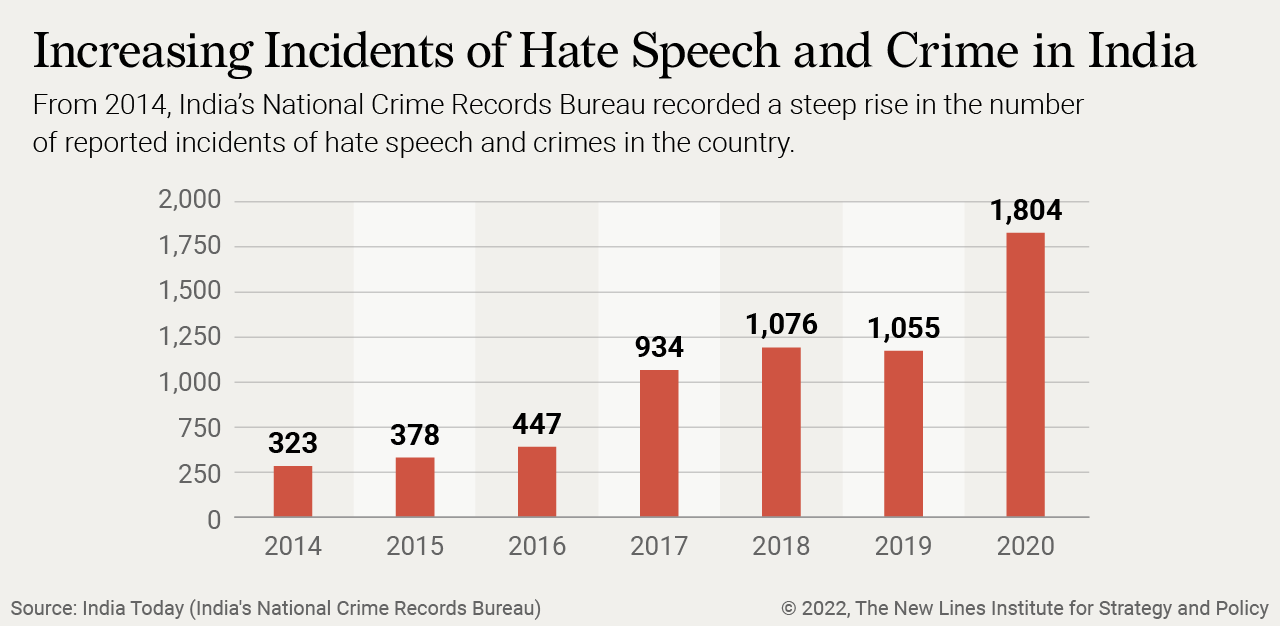

Consider, for instance, how former President Donald Trump’s 2020 visit to India coincided with a brutal crackdown against months of protests. The demonstrations in question were sparked by a controversial amendment that aims to fast-track citizenship for migrants from many religious minorities, but not for Muslims. Not only did Trump ignore these protests, he praised Modi for “working very hard on religious freedom.” Conversely, international organizations such as Genocide Watch and even the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum have described India as being on the brink of genocide. Indeed, the dehumanization of people through hate speech, and the increase in hate crimes in India, are considered precursors to genocidal violence. Genocide Watch founder Gregory Stanton, who predicted the Rwandan genocide, gave a recent briefing to the U.S. Congress during which he warned that “genocide could very well happen in India”. Stanton has also apparently advised Congress to pass a pre-emptive resolution warning India about the dire consequences of genocidal violence. He recommended that the Biden administration explicitly inform the Indian leadership that if genocide does occur in India, the U.S. will be left with no choice but to reassess its relations with the country.

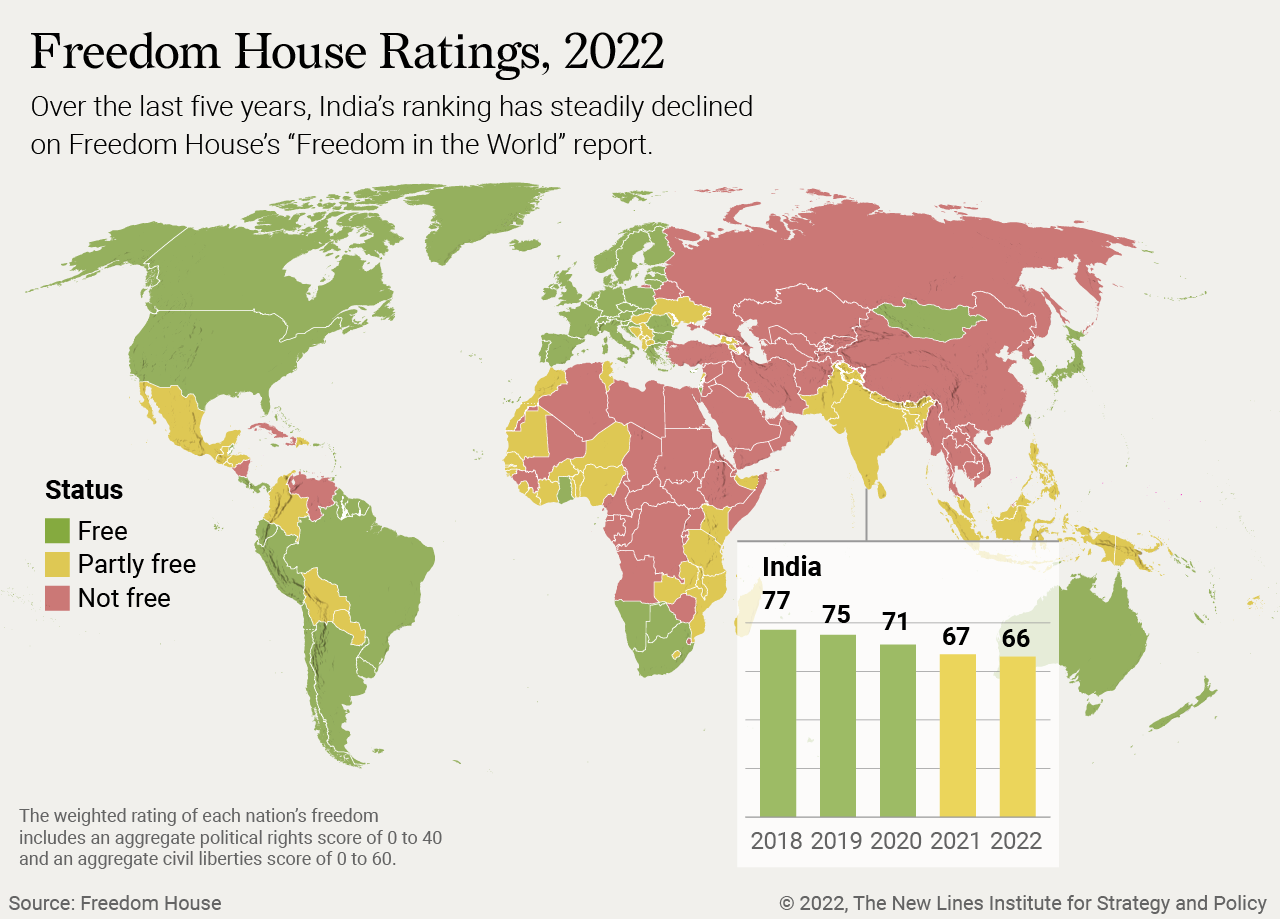

Independent entities like Human Rights Watch and Freedom House have also been tracking the steady erosion of democratic values and the rise of human rights abuses across India. Freedom House’s Freedom in the World 2021 report lowered India’s ranking from “free” to “partly free.” The U.S. itself has expressed concern about the muzzling of dissenting voices; the misuse of terrorism and sedition laws; the illegal detention of rights activists; the carrying out of violent attacks against Muslims and Christians; and interference with the work of local and international NGOs, as well as other development agencies.

The influence of U.S. admonishment cannot be overstated. Concern expressed by U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken regarding India’s human rights record, for instance, has been met with cynicism and rebuttals pointing to America’s own problems with racism and its high imprisonment rates. Yet persistent pressure by progressive lawmakers has led the Biden administration to become more aware of the growing human rights problems in India and to give these issues greater weight within the bilateral relationship, for instance when the State Department promptly expressed concern about the recent blasphemy controversy. However, the incitement of anti-Muslim sentiment in India is a much more pervasive and longstanding problem.

More explicit and more frequent recognition by senior U.S. policymakers of the growing human rights abuses and intolerance across India could help steer India’s present leadership away from its dangerous trajectory of intolerant ethno-majoritarianism. There are established mechanisms the Biden administration can use that will show its resolve to take the rise of intolerance within India more seriously. For three years in a row, the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom has asked the State Department to include India in its list of “Countries of Particular Concern” for egregious violations of religious freedoms, but the State Department has not taken that step.

It is imperative that the State Department designate India as a Country of Concern. Not doing so will only allow countries with such designation, including China and Pakistan, to dismiss the Commission’s ranking as biased. The repeated omission of India from the list of countries where serious violations are impeding religious freedom undercuts the very foundation of America’s effort to build a solid relationship with India: a shared commitment to democratic values.

The U.S. cannot impose unilateral influence on protracted territorial disputes between India and Pakistan, especially given India’s insistence that it does not want third-party mediation. The U.S. can, however, take a firmer stance against state repression and human rights violations in Jammu and Kashmir, which remains a dangerous flashpoint for conflict on the Indian subcontinent.

The U.S. recognizes that climate change is increasing food insecurity and water stress in India. These human security challenges will worsen over time, causing severe cross-border tensions within the broader region as glacial melt stresses transborder river systems shared by India, China, Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, and Bhutan. The U.S. can help pre-empt the threat-multiplying risks associated with this growing water stress by encouraging and supporting cooperation between India and its adjoining states. These states must work together to improve their inadequate river-basin management capabilities and to develop institutional mechanisms to resolve climate-induced water disputes.

If India’s emergent model of majoritarian democracy remains unchallenged, the resulting marginalization of minorities and the growing restiveness within the country could cause major destabilization. This will diminish India’s value as a reliable and relevant partner for the U.S. to contain China. The persecution of Muslims in particular raises the risk of militant reprisals, which could spark conflict with neighboring Pakistan. Such a conflict could spiral out of control, unleashing catastrophic consequences for the broader region and beyond. Preventing such dire consequences requires not only bolstering India’s conventional security capabilities but also helping alleviate its emergent human security threats, even as great-power competition heats up in South Asia.

Dr. Syed Mohammed Ali is a professor of anthropology, international development, and human security courses at Johns Hopkins, Georgetown, and George Washington universities. Dr. Ali has two decades of experience working on major international development challenges including governance problems, issues of marginalization, and natural and man-made disasters. Ali is the author of Development, Poverty and Power in Pakistan: The Impact of State and Donor Interventions on Farmers (Routledge, 2015).

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not reflective of an official policy or position of the New Lines Institute.