An increasingly concerned U.S. Congress has tasked the Department of Defense (DOD) with assessing its ability to sustain major operations in the Pacific. However, Congress’ “security-first” approach to the region only partly aligns with requests from Washington’s partners in Southeast Asia who want access to U.S. markets and investment. This emphasis on military operations also neglects ongoing regional climate change challenges that will grow more acute over the next few decades.

The DOD should consider the state of Southeast Asian electric grids in its assessments. Grids in the region play a role in regional security and competition with China. Moreover, by working with regional partners to upgrade the regional grid, the United States can provide an economic investment that prepares the region for the challenges of climate change. The DOD has the personnel, funding, and most importantly congressional will to build sustainable grids in Southeast Asia that will enable future U.S. force projection, improve U.S. allies’ energy stability, and strengthen relationships between Washington and its Southeast Asian allies by investing in local economies.

Economics, Climate, and Energy

U.S. Indo-Pacific allies consistently declare U.S. economic engagement a top priority over defense. Economic success is seen as a key pillar of regime stability, especially in Thailand. However, the historically strong trade diplomacy between the United States and Southeast Asia has faltered since the U.S. withdrew from the Trans-Pacific Partnership in 2017. Congress has had a faint appetite for major trade deals since then. However, improving the region’s energy infrastructure would serve both U.S. and Southeast Asian interests.

Grid improvements would serve economic interests in Southeast Asia by enabling the adoption of more green energy – which, in turn, would improve the grid. Old grids limit the adoption of renewable energy in many Southeast Asian states by not physically reaching renewable energy sources or sustaining additional electrical capacity; incorporating more green energy would improve the grid’s long-term resilience. Hardening grid infrastructure would protect against climate-driven extreme weather such as heat waves or heavy rains and flooding. Most climate finance focuses on short-term measures to help vulnerable countries mitigate climate change’s impact, but funding new grids in Southeast Asian countries would be a form of adaptation to climate change aimed toward long-term success.

Grids that run on renewables would be less vulnerable to pricing changes in global energy markets, would promote economic activity, and would better weather energy market instability in the event of increased conflict with China. A more efficient grid fuels better energy for economic production while reducing the amount of CO2 released. As seen in the case of Taiwan, setting up advanced manufacturing and high technology factories requires plentiful and stable energy. Improved grids, supported by renewable energy, do more than just insulate against international energy market volatility and climate motivated disasters. Efficient energy transfer and storage, backed by strong electrical production plants, is a prerequisite for next-generation, high-tech manufacturing coming to Southeast Asia over the next decade. The DOD’s contributions can be a piece of this transition. Should U.S. China competition in the Indo-Pacific become more intense, grids that support energy needs of modern systems could insulate Southeast Asian economies from economic competition.

By investing in modernized grids for U.S. regional partners, the United States creates more economically successful partners that will both see the United States as a source of support and have the economic ability to follow the United States into strategic competition. While not a perfect remedy to Southeast Asian leaders’ desire for more economic cooperation, it will show that the United States is flexible in attempting to meet their concerns with action.

Meanwhile, the DOD, especially the Navy, needs efficient and powerful energy sources to sustainably continue force projection. While hydrogen- and nuclear-powered ships will be able to sustain themselves, inland force projection will have an increasing demand for electricity. With DOD investments in these grids, future force projection can be enabled. Sustaining supplies therefore will fall to the energy that the DOD can bring in or energy provided by allies and partners. The DOD has funding, personnel, and Congress’ blessing to prepare for competition in the Indo-Pacific, and the State Department’s Bureau of Political-Military Affairs already coordinates U.S. military activities with these partner nations in Southeast Asia. The DOD’s resources and the State Department’s expertise and authority are well-suited to taking on defense efforts that include grid improvements in the region.

Energy Use in Southeast Asia

Energy is lost in transit on old or poorly designed grids, necessitating the increased burning of fossil fuels. U.S. partners in Southeast Asia are in the top 10 for global measures of inefficient grids, with the region’s combined rate second only to Saudi Arabia. U.S. ally Thailand is the 8th most inefficient globally, and Malaysia is 7th. Modernizing regional grids means better outcomes wherever the United States would look to operate in the region. An investment in one Southeast Asian electric grid is an investment in all, as regional electricity production is shared between countries.

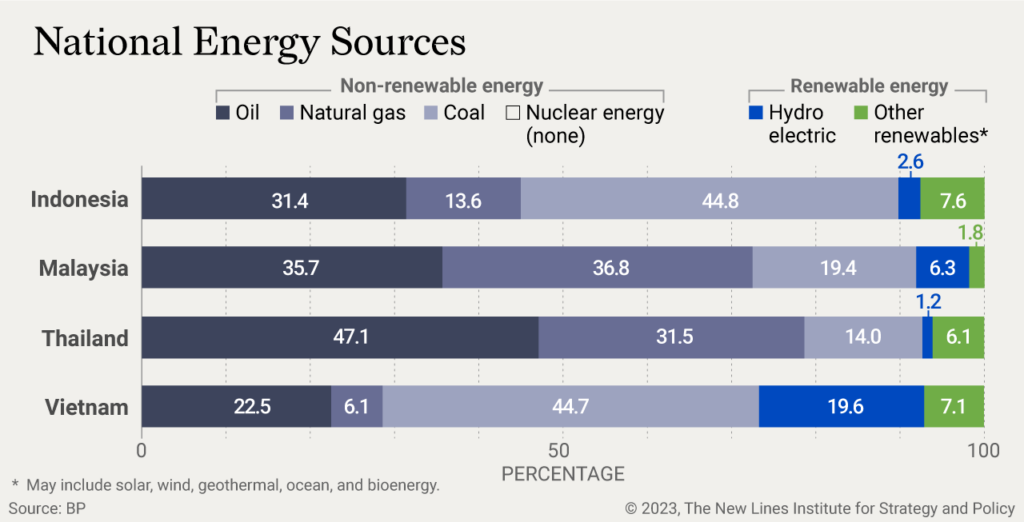

As demonstrated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, global energy markets are deeply interconnected. The vast majority of Southeast Asia’s fossil fuel imports are from the Middle East rather than China, but any U.S.-Chinese conflict would greatly impact the affordability of the oil imports that make up just over a third of regional energy needs. Building grids that use domestically produced renewable energy sources would insulate Southeast Asian economies in the event of crisis while addressing various climate change challenges.

Typical assessments of a country’s energy production include bioenergy, which has civilian applications, but U.S. policymakers should be wary of this energy source when considering DOD investments. Bioenergy – which typically comes from burning wood or plant material from crops – is an alternative to fossil fuels that makes up just under 4% of energy production in Association of Southeast Asian Nations members. Most types of bioenergy lack the energy density to power next-generation manufacturing or defense investments. Energy-dense biodiesel, often made from palm oil in this region, can power transportation and manufacturing, but is hampered by the myriad social and environmental costs of palm oil production.

Bioenergy can play a role in replacing fuels, but comes with its own negative environmental effects, such as increased deforestation and air pollution. For example, Vietnam remains least dependent on fossil fuel imports, due to its dependence on coal and high use of renewables (a leader in the use of renewable energy, Vietnam regularly adopts policies that are friendly to solar and wind energy). This insulates Vietnam from more volatile oil and liquefied natural gas market pricing. However, Vietnam’s leadership in renewable energy is predicated on biofuel, which constitutes 57% of Vietnam’s renewable energy production.

Southeast Asian countries will require $5 trillion to adopt renewable energy sources and supporting infrastructure by 2050.

However, system loss can be addressed on a shorter timetable with less funding than other lines of effort. In many cases, system loss can be addressed by rebuilding old and inefficient power lines. Grid updates can begin today with existing technology. Power transition, distribution, and storage are estimated to cost just over $169 billion by 2030, by contrast adopting electric vehicles region wide would cost $652 billion by 2030. Renewable fuels are not as energy dense as fossil fuels, meaning grid efficiency is key to enabling their adoption. While each country and region have its own challenges and opportunities, replacing power cables, updating transfer stations, and improving regional capacity storage will also make better use of the fossil fuels that are being burned.

Recommendations

The DOD can take two steps toward building sustainable and powerful grids in Southeast Asia.

First, as the DOD assesses its own ability to fight and win in the Indo-Pacific, it should include a comprehensive assessment of local energy grids. Additionally, the DOD and U.S. government should acknowledge the challenges of bioenergy, including deforestation and air pollution, in their assessments. Reframing these fuels as a liability rather than a sustainable solution will improve outcomes for both grid reliability and the environment. Future efforts for aiding Southeast Asian governments cannot begin without an initial assessment of the existing grids, regardless of which U.S. department takes on the development effort.

Second, the DOD can operationalize its findings, making use of its engineers on annual rotation on the Pacific Pathways military exercise series. These servicemembers are technical experts who have built relationships with their counterparts in Southeast Asian countries – mainly Malaysia, Indonesia, and Thailand. Scheduling these construction activities, or advising on construction, can be handled by local State Department bureaus, which are already involved in annual and semiannual exercise planning. Initial projects will likely start small but can grow as connections and trust are built. This is already similar to construction events in Thailand, where U.S. servicemembers build public infrastructure like school buildings.

Climate change and geopolitical competition will be strategic challenges for not just the United States but also its Southeast Asian partners. Furthermore, U.S. allies in the region have repeatedly expressed their desire for stronger economic ties with Washington. The DOD has received new funding that can be used to address all these issues. Each country in the region will benefit from tailored policy; despite unified issues with infrastructure, each country’s situation and politics are unique. Grid modernization is a ready opportunity for the DOD to secure against both a conflict with China and a changing environment.

Alec Dionne is the External Relations Manager at The New Lines Institute. Alec has worked on issues of public affairs and national security for the past seven years, focusing on projects in Northern Syria, Malaysia, Iraq, Ukraine, and Australia. Recently, Alec has researched Indo-Pacific Security, writing strategy documents for Boeing Defense Space and Security, and the Department of the Navy. These efforts have focused on optimizing U.S. strategy for great power competition and grey zone conflict. Alec’s work in the Middle East centered on building non-sectarian institutions to address U.S. regional adversaries, primarily the Islamic State. He tweets at @Alec_Dionne.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of the New Lines Institute.