An Analysis Of Various International Responses To The Conflict In Myanmar Compared With That In Ukraine

Introduction

The Russian invasion of Ukraine is undoubtedly the largest ongoing conflict in the world today. The death toll stands at tens of thousands, and the mass displacement of people as a consequence of the conflict amounts to millions. More than $150 billion in bilateral aid alone has been spent on the war effort in Ukraine by its allies.i Without an end to the war in sight, this spending could continue for months if not years. The international responses to the conflict have been extensive from the political to the humanitarian fronts, and they continue to be so.

In addition to the Ukrainian-Russian conflict, there are several other ongoing conflicts in the world today. These include conflicts in Myanmar, Ethiopia, Yemen, Palestine, Syria, and Sudan, to name a few. This paper focuses on one of these conflicts – the conflict in Myanmar – and how the responses of the international community to the Myanmar conflict have contrasted to those for Ukraine.

Before we begin, let us define the terms “conflict” and “international response,” as seen in the scope of this paper. We shed light on the historical background of the two conflicts, and their international responses thus far, before doing a comparative analysis.

Definitions

Conflict

The Cambridge Dictionary defines conflict as “an active disagreement, as between opposing opinions or needs” and as “fighting between two or more countries or groups of people.”ii Merriam-Webster defines conflict as “a competitive or opposing action of incompatibles” and as “a fight, battle or war,” among other definitions.iii

For the purpose of this paper, we utilize conflict in the sense of armed fighting between two or more groups of people from different countries or from within the same country.

International Response

The Cambridge Dictionary defines international as “involving more than one country,”iv while Merriam-Webster’s definition of international is “connected with or involving two or more countries.”v

The Cambridge Dictionary defines response as “something said or done as a reaction to something that has been said or done,”vi while Merriam-Webster’s definition of response is “something constituting a reply or a reaction.”vii

In this paper, we view international response as what has been said and done by countries worldwide as a reaction to the conflicts being discussed.

Historical Context

Ukraine

The current war in Ukraine began in 2014, when Russia annexed Crimea on the pretext that Crimea was a Russian-speaking region that had always been a part of Russia.viii In the years after the annexation, Russia continued to support other separatist factions in the Donbass region of eastern Ukraine. Localized conflicts between pro-Russian separatists and the Ukrainian government’s forces continued in eastern Ukraine until February 24, 2022, when Russian forces launched an invasion operation.ix

The Russian invading force made significant gains within the first few days/weeks; however, it gradually withdrew from areas it had captured, mainly in the north and northeast of Ukraine. The Russian presence continues to persist in the south and southeastern parts of Ukraine, primarily in the Crimea, Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhia, and Kherson regions.x

Russia has targeted Ukraine’s ports and other economic infrastructures. Ukrainian forces have launched successful counteroffensives in major cities and urban centers, with the help of arms and munitions supplied by foreign governments.xi

There are multiple root causes of the conflict. Russia and Ukraine share significant historical and cultural ties. As a former Soviet colony, Russia sees Ukraine as its region of socioeconomic and political influence. Ukraine, on the contrary, has shown an inclination toward the West, and has expressed interest in joining the European Union as well as NATO.xii The latter was particularly seen by Russia as a threat to its own security, and hence was the pretext for the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.xiii

The civilian death toll from the war is estimated at nearly 9,300 by the U.N.xiv Military casualties, according to Reuters’ latest estimates, are 15,500-17,500 Ukrainians and 35,500-43,000 Russians.xv

Myanmar

The current war in Myanmar started with the military coup on February 1, 2021. Myanmar’s commander in chief, Min Aung Hlaing, ordered the coup on the pretext that the results of the 2020 fall elections were rigged. The country’s reelected de facto leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, and her party members were subsequently arrested and imprisoned by the military.xvi

Nationwide protests erupted immediately after the coup. The military responded with a violent crackdown on the protesters.xvii The protesters organized themselves into armed groups, under the umbrella of the People’s Defense Forces, an armed extension of the National Unity Government, a government-in-exile that was primarily formed by leaders of Suu Kyi’s party. The People’s Defense Forces formed new collaborations with ethnic armed factions that were already in direct conflict with the military.xviii Consequently, Myanmar entered into a full-scale civil war.

The root causes of the war, apart from the coup d’état that followed the violent crackdown, trace back to colonial period and postcolonial rule, when the country faced serious challenges in nation-building. Military rule took over the country within a decade after independence. Tensions rose between the various minorities and the majority Bama population for land, resources, religion, and other socioeconomic reasons. There are more than 135 ethnic minorities in Myanmar, some of which are not even recognized officially by the Burmese government. Most of the major ethnic minorities have established their own jurisdictions and guerilla forces as their way of self-determination.xix

The death toll resulting from the ongoing civil war is difficult to verify, though figures as high as 38,000 are estimated to have been killed since February 2021, according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project.xx Large-scale displacement of refugees into Thailand and other neighboring states continues. Severe human rights abuses – including extrajudicial killings, sexual violence, scorched earth, and indiscriminate attacks on civilian populations – are well documented in the case of the Myanmar civil war. In addition, the slow genocide continues against Rohingya minorities in northwestern Myanmar through severe restrictions of movement, economic activity, and access to aid.xxi

International Responses to the Conflict in Ukraine

The international responses to the conflict in Ukraine are manifested in a wide variety of domains, ranging from media to economic aid to political actions to military assistance. This is in addition to international humanitarian aid and responses from civil society organizations.

Media Coverage

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 triggered a sudden surge in international media coverage on “the war in Europe.” News outlets worldwide reported the invasion in real time, particularly on the wide-scale destruction and civilian casualties. The coverage highlighted the seriousness of the crisis and its implications for security in Europe and globally.xxii

It was not too long before bias in media narratives could be observed, with certain outlets emphasizing specific aspects of the conflict over others, primarily based on their country’s geopolitical interests. Western media outlets emphasized Russia’s aggression and violation of international law. They highlighted Ukraine’s struggle for sovereignty and its freedom to choose the influence it preferred.xxiii

On the contrary, the Russian media portrayed the invasion as a necessary response to protect Russian-speaking populations in Ukraine and alleged the presence of far-right elements in the Ukrainian government. They also accused Western countries of meddling in Ukraine’s internal affairs and promoting an anti-Russian agenda.xxiv

Social media platforms played a crucial role in disseminating information during the crisis. Platforms like Twitter (now X), Facebook, and YouTube allowed individuals on the ground to share real-time updates, videos, and images, providing a glimpse into the conflict’s human cost. Both sides of the conflict used social media to push their narratives, leading to an “information war” in cyberspace. However, the sheer volume of information and the lack of verification processes also led to the spread of misinformation and propaganda.xxv

Economic Actions

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) was among the first organizations to provide bailout support to Ukraine. It has provided a $115 billion global package, which includes $15 billion in loans, $80 in concessional grants from multilateral institutions and countries, and $20 billion in debt relief.xxvi

Apart from the IMF, other international financial institutions have played a vital role in providing economic aid to Ukraine. The World Bank has mobilized over $37.5 billion to assist Ukraine in fulfilling essential needs and rebuilding its economy.xxvii The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) also extended financial support to Ukraine’s businesses and economy, committing €3 billion over 2022 and 2023.xxviii

Numerous countries have and continue to provide bilateral aid to Ukraine, signaling their solidarity and commitment to the country’s struggle during the war. The top donor nations are the European Union, the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia, among other nations. The United States itself has provided nearly €25 billion in financial assistance, followed by €5.6 billion from Japan, and nearly €4 billion and €3.5 billion from the U.K. and Canada, respectively.xxix

The European Union has offered the largest amount of bilateral financial aid to Ukraine, €27.3 billion. This is not including aid from other European states – such as Norway, the Netherlands, France, and Poland – which each have provided €0.7 billion to €1 billion in financial aid.xxx

The figures given here are only for financial aid, and they exclude humanitarian and military assistance, which were provided in addition to economic assistance. The sheer amount of economic aid demonstrates the international community’s unwavering solidarity with Ukraine.

Military Aid

The United States has provided $46.6 billion in military aid to Ukraine as of July 2023. This aid includes long-range rocket artillery systems, ammunition, counterfire radars, air surveillance radars and drones, antitank missiles, and coastal defence systems. The aid has enhanced Ukraine’s ability to deter Russian aggression and strengthen its ground and air defense capabilities.xxxi

In addition to the United States, several other countries – including the United Kingdom, Canada, Lithuania, and Poland – have also provided military equipment – such as armored vehicles, rifles, and communications systems – to support Ukraine’s defense forces.xxxii Alongside military equipment, international partners have offered military training and advisory support to Ukraine’s armed forces. In particular, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada have sent military advisers and trainers to Ukraine to provide expertise on tactics, intelligence, and strategic planning. These trainers have helped train tens of thousands of Ukrainian troops to enhance their capabilities and coordination.xxxiii

International military aid to Ukraine has not been limited to bilateral support. Multilateral military cooperation and joint exercises have played a crucial role in strengthening Ukraine’s defense capabilities. NATO member states have constantly participated in military drills and exercises in Eastern Europe, reinforcing and creating new battle groups in the region. NATO’s members have sent ships, aircraft, and troops to Eastern Europe to increase their deterrence posture against potential further Russian aggression in the region.xxxiv The provision of international military aid to Ukraine demonstrates the international community’s unwavering commitment to deterring Russia’s war in Ukraine.

Humanitarian Aid

Numerous international organizations have played a vital role in providing humanitarian aid to Ukraine since the onset of the conflict. The United Nations and its various agencies – including the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the World Food Program (WFP), and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) – have been actively engaged in delivering life-saving assistance to affected civilians.xxxv

The UNHCR has focused on providing shelter, essential supplies, and support for displaced populations within Ukraine and those who have fled to neighboring countries. The WFP has been instrumental in distributing food aid to those facing food insecurity due to the conflict, while UNICEF has been working to ensure access to education, healthcare, and protection services for vulnerable children.xxxvi

In addition to the U.N., a multitude of humanitarian organizations have also been on the ground, providing essential relief and support in conflict-affected areas. Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders) spent $50.5 million in Ukraine in 2022, and the American Red Cross alone contributed $53 million to Ukraine relief efforts through August 2022.xxxvii The Canadian Red Cross raised Can$1.25 billion as of July 2022.xxxviii

Aid from governments has also added to the immense outpouring of humanitarian assistance to Ukraine, notably:

- €570 million from January to November 2022 by the Austrian governmentxxxix

- €800 million from Belgium by April 2022 (within 2 months of the start of war)xl

- CAD$500 million from Canada by November 2022 on Ukraine Sovereignty bondsxli

- €190 million from Denmark by January 2023xlii

- €420 million from Lithuania by December 2022xliii

- €118 million from the Netherlands by July 2023xliv

- €1.3 billion per year for five years from Norwayxlv

- $100 million from Qatarxlvi

- $400 million from Saudi Arabiaxlvii

- $100 million from South Korea in 2022xlviii and $130 million in 2023xlix

- $1.3 billion from Switzerland donated by February 2023

- $1.9 billion from Germany and $1 billion from Japanl

- $3.6 billion from the U.S., and $2.1 billion by the EUli

These figures do not include many countries that have given less than $100 million, and they also exclude material and equipment support provided by numerous nations for the reconstruction and repair of shelters, and the distribution of essential nonfood items like blankets, hygiene kits, and cooking supplies.

This international humanitarian aid has demonstrated unparalleled global solidarity with Ukraine and conveyed a message of compassion and support to the affected population unlike anywhere else.

Other Political Actions, Including Sanctions

One of the immediate responses to the Russian invasion was a wave of international condemnation. Around the globe, countries publicly criticized Russia’s actions, declaring their support for Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity.lii At the U.N. General Assembly in March 2022, 141 countries voted in favor of a resolution demanding Russia to immediately end its military operations in Ukraine.liii In another General Assembly resolution in September 2022, 143 countries condemned Russia’s annexation of four eastern regions of Ukraine.liv

Diplomatic efforts were also undertaken to find a resolution to the crisis through dialogue and negotiations. Multiple rounds of talks were initially held between Russian and Ukrainian representatives, with the involvement of international mediators such as Turkeylv and Belarus,lvi in an attempt to reach a cease-fire and deescalate the conflict. Later on, numerous propositions for peaceful resolution were provided by Brazil,lvii Saudi Arabia,lviii China,lix and South Africa.lx However, a lasting resolution could not be reached.

The U.S., U.K., EU, and their allies imposed severe economic sanctions on Russia. The sanctions came in various forms: from financial to goods and services to targeted sanctions on individuals and businesses.

Through the EU’s sanctions, nearly half of foreign Russian reserves became frozen,lxi nearly 49% of EU exports to Russia (compared with 2021) became controlled,lxii and nearly 90% of Russian oil imports to Europe became restricted.lxiii

Financial sanctions began with disconnecting Russian banks from the international swift payment system in efforts to slow down Russian entities from receiving payments for their commerce.lxiv Further financial sanctions cut off $350 billion in foreign currency reserves.lxv

Sanctions in the oil and gas sector were most prominent with the U.K. and the U.S. banning all oil and gas imports from Russia.lxvi Germany stopped the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline from entering Russia, a project worth $11 billion.lxvii Russian crude oil was capped at $60 a barrel by EU nations.lxviii

A ban on exporting technological goods that could potentially be used for military purposes (including items such as vehicle parts) was put into effect by the U.S., the U.K., and EU member nations.lxix Over 1,000 multinational companies have also voluntarily curtailed their operations in Russia.lxx

Thousands of targeted sanctions on Russian oligarchs, close allies of the Kremlin, and businesses in Russia were placed by the United States, the United Kingdom, the EU, and their allies (including Canada, Australia, Japan, and South Korea).lxxi

The above-noted sanctions target key sectors of the Russian economy and its individuals, aiming to weaken Russia’s position in the war and discourage further aggression. They demonstrate a relentless pursuit by major actors globally to halt Russia from perpetuating the war. For example, just the EU implemented 11 different waves of sanctions as of June 2023, with successive additions in each wave including additions of measures that strengthen bilateral and multilateral cooperation with third countries in efforts to impede sanctions’ circumvention by Russia.lxxii

Civil Society Responses

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 triggered a strong global response from civil society organizations around the world. From human rights groups to humanitarian agencies, academic institutions to advocacy networks, civil society entities mobilized to condemn the aggression and support the people of Ukraine.

International civil society organizations used their platforms to advocate for peace, human rights, and justice in Ukraine. They organized awareness campaigns, public demonstrations, and petitions to raise awareness about the conflict and its humanitarian implications.lxxiii Through social media and public events, these organizations called on the international community to support Ukraine’s sovereignty, protect civilians, and find a peaceful resolution to the crisis.lxxiv

Numerous human rights groups and organizations have closely monitored and continue to monitor the human rights situation in Ukraine during the invasion. They have documented alleged human rights violations, abuses, and attacks on civilians, bringing attention to potential war crimes and violations of international law.lxxv Their reports and investigations will form the basis of critical evidence for holding perpetrators accountable for justice and redress.lxxvi

Academic institutions and civil society networks have engaged in educational and research initiatives to shed light on the complexities of the conflict. Their in-depth analysis, reports, and conferences help establish an unbiased understanding of the geopolitical, historical, and social factors exacerbating the crisis.lxxvii These efforts are instrumental in informing policymakers and the public about the broader context of the conflict.

Smaller, localized civil society organizations played significant roles in resettling refugees who fled the conflict in Ukraine. They provided essential services – such as shelter, food, healthcare, and legal aid – to those who crossed the border to take shelter in neighboring countries in Europe.lxxviii They worked to address the long-term needs of displaced individuals and support their integration and well-being in host communities.lxxix Many church groups in the U.S., U.K., Canada, Germany, and the like helped with the resettlement of Ukrainians displaced by the war.lxxx

As of August 2023, there were nearly 6.2 million Ukrainian refugees worldwide, with 5.8 million in Europe and 358,000 outside Europe.lxxxi The countries hosting the largest number of Ukrainian refugees include Russia, with nearly 1.3 million refugees; Germany, with nearly 1.1 million; and Poland, with nearly 1 million.lxxxii In each of these countries (and all others hosting the refugees), civil society organizations play a major role in helping with resettlement.

International Responses to the Conflict in Myanmar

The international responses to the conflict in Myanmar can now be viewed through the lenses of media coverage, economic activities, military aid, humanitarian assistance, political actions, and civil society involvements to see how they contrast with the responses received for Ukraine.

Media Coverage

Myanmar is one of the countries with the highest amount of media censorship. According to Reporters Without Borders’ world freedom of press index, Myanmar stands in the bottom 10 countries in the world.lxxxiii

As of January 30, 2023, Reporters Without Borders recorded at least 130 journalists arrested and jailed in Myanmar, of which 72 were still being held in prisons, with reported cases of torture. They recorded a drastic increase in crackdowns on press freedom in Myanmar since the coup d’état.lxxxiv

The Committee to Protect Journalists, a nonprofit organization dedicated to protecting journalists worldwide, says that Myanmar ranks among the worst jailers for journalists, as per the committee’s prison census. It points out how Myanmar’s ruling junta has jailed journalists and murdered at least three of them while they were in custody.lxxxv

Parts of Myanmar – like the northwestern province of Rakhine, where the Rohingya population live – have been off limits to journalists and international NGOs numerous times.lxxxvi Despite condemnations from rights groups and the U.N.’s Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, access remains an unresolved issue.lxxxvii

Within a month of the coup d’état, five major independent news outlets – Mizzima, DVB, Khit Thit Media, Myanmar Now, and 7Day News – were banned from broadcasting, and had their licenses revoked. State-controlled broadcasters – like MRTV, Global New Light of Myanmar, Myawady TV, and Myanmar New Agency – continued to operate, primarily to spread government propaganda.lxxxviii

Fast forward two years later: Mizzima has survived and has become a trusted independent source of journalism. Three other news outlets – Democratic Voice of Burma, BBC Burma, and Voice of America – have also become known as reliable independent news sources. However, sustaining their operation continues to be a challenge, given drastic declines in revenue from digital advertising.lxxxix

The junta also put severe restrictions on internet and satellite TV within months of the coup d’état. Internet access in some regions was completely shut down, and in other areas it was severely reduced. Those carrying satellite dishes to connect to satellite television faced fines or prison time.xc For journalists reporting day-to-day activities from the ground, the lack of access to the internet is a severe blow to their ability to function.xci In conflict-affected areas, having or not having the internet could sometimes mean the difference between life and death, since the internet is used to securely communicate information and early warning on the movement of junta troops before they attack a village.xcii

For those who are able to receive some internet access, social media became their platform to disseminate information to the rest of the world. Ethnic human rights organizations, as well as prominent grassroots organizations that emerged during nationwide protests against the coup, took to Facebook and Twitter to disseminate news through their social media accounts. However, this also led to campaigns of misinformation, propaganda, and hate speech affecting the groups involved.xciii

At the start of 2023, the military began an online campaign of terrorism to debilitate democratic opposition, especially targeting female activists. The OHCHR has called for social media companies to allocate necessary resources to protect the rights of users in Myanmar.xciv

Economic Cooperation

The violent crackdown on civilian protesters by Myanmar’s military and the subsequent activism backlash by Burmese and international civil society created immense pressure on international corporations to reconsider their investments in Myanmar. As a result, a large number of multinational corporations ended up divesting from Myanmar, including, but not limited to, these:xcv

- The Japanese brewery Kirin

- The South Korean steelmaker POSCO

- The Norwegian telecommunications giant Telenor

- France’s Total Energy and the U.S. petroleum giant Chevron

- Malaysia’s Petronas and Thailand’s PTTEP

- Switzerland-based Nestlé Corporationxcvi

While the worsening human rights situation was the main reason for the departure of multinationals, other factors included lawlessness and deteriorating economic conditions.xcvii

As the above-noted multinational corporations made their tough decisions to exit from Myanmar, a few others made the decision to stay or begin new investments. These include:

- The Israeli software maker Cogynte, to supply spywarexcviii

- India’s Adani Group, to increase its investments in Yangon port developmentxcix

- Singapore-based firm Yoma MFS Holdings, to buy a 51% stake in Wave Money from Norway’s Telenorc

- Russia, to supply missile systems, drones, radar systems, helicopters, and fighter jetsci

- China, to increase border trade, investments, and cooperation on energy and electricitycii

While Myanmar’s gross domestic product (GDP) fell from $65.1 billion in 2021 to $59.3 billion in 2022, its GDP growth rate has increased, from –17.9% in 2021 to 3.0% in 2022.ciii

Myanmar’s top trading partner countries for export in 2022 wereciv:

- Thailand, at $3.85 billion and 23% of Myanmar’s total exports

- China, at $3.69 billion and 22% of Myanmar’s total exports

- Japan, at $1.21 billion and 7.1% of Myanmar’s total exports

- India, at $900 million and 5.3% of Myanmar’s total exports

- The United States, at $761 million and 4.5% of Myanmar’s total exports

- Germany, at $679 million and 4.0% of Myanmar’s total exports

- The U.K., at $623 million and 3.7% of Myanmar’s total exports

The top trading partner countries for imports in 2022 were:cv

- China, at $5.6 billion and 32% of Myanmar’s total imports

- Singapore, at $4.3 billion and 25% of Myanmar’s total imports

- Thailand, at $2.1 billion and 12% of Myanmar’s total imports

- Malaysia, at $1.1 million and 6.6% of Myanmar’s total imports

- Indonesia, at $1.0 billion and 6.0% of Myanmar’s total imports

- India, at $562 million and 3.3% of Myanmar’s total imports

- Vietnam, at $394 million and 2.3% of Myanmar’s total imports

Humanitarian Aid

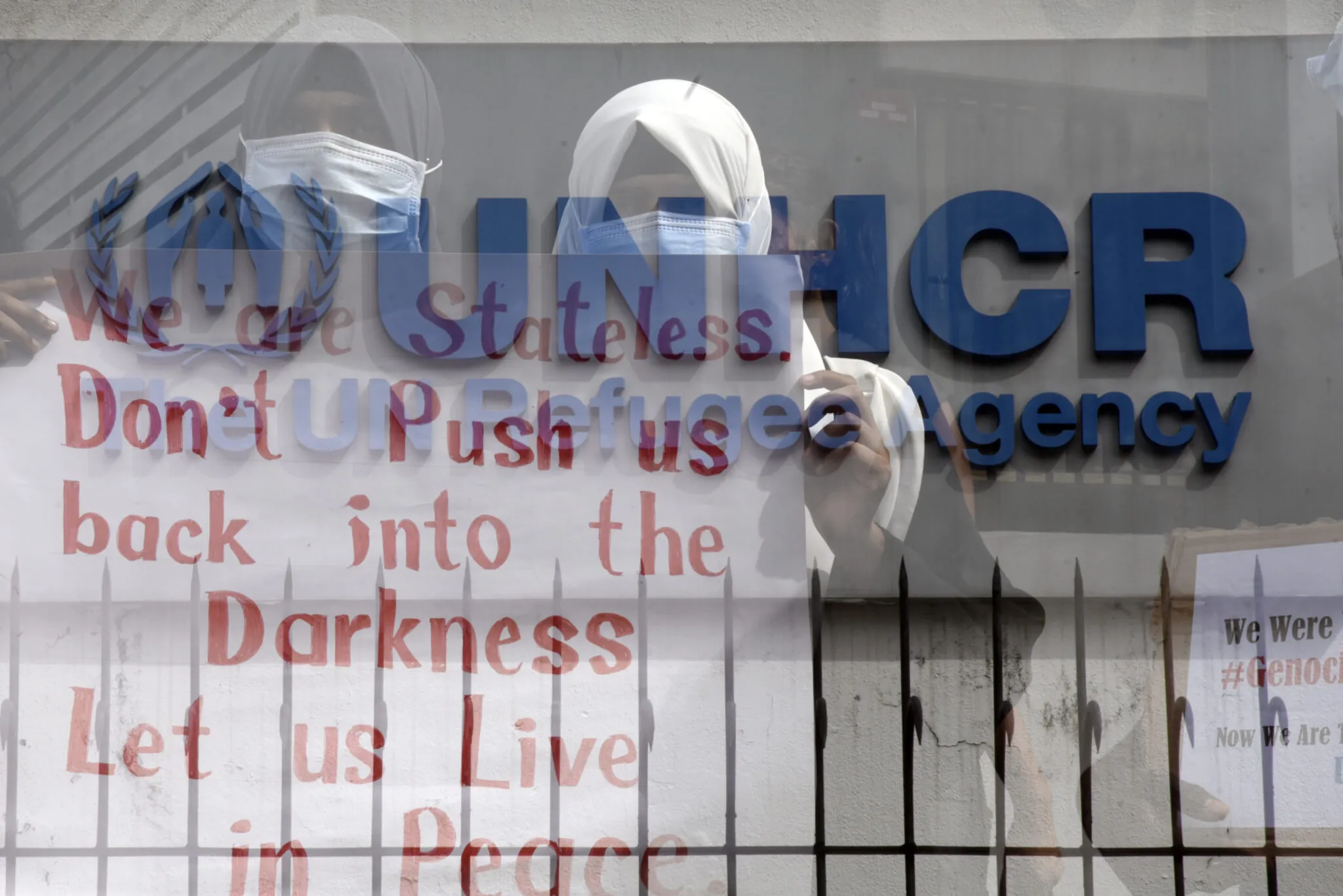

Myanmar is one of the poorest countries in Southeast Asia, with GDP per capita among the lowest in the region.cvi According to the European Commission, nearly 17.6 million people in Myanmar are in need of aid as of 2023.cvii Many U.N. agencies – including the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), and the World Food Program (WFP) – have been involved in delivering aid to vulnerable populations and displaced persons inside Myanmar. Large international NGOs – like the International Committee of the Red Cross, World Vision, Oxfam, and Save the Children – are also active on the ground delivering aid wherever they have access.cviii The U.N. humanitarian response plan at the start of 2023 forecasted $764 million for 4.5 million people prioritized for life-saving humanitarian support.cix Historically, only a small fraction of the amount needed is received by the donor community. In 2021, the year that saw the coup d’état and violence that followed immediately afterward, only 18% of the $109 million requested was fulfilled by the international community.cx

Unfortunately, aid access is a severe problem in Myanmar.cxi Access to aid is primarily restricted by the ruling military junta, which has systematically denied humanitarian aid to the millions of civilians in need of relief.cxii The junta government has imposed travel restrictions on aid workers, blocked roads and convoys, attacked aid workers,cxiii and turned off the internet and telecommunications, thereby making it almost impossible to deliver aid.cxiv

The largest humanitarian donor to Myanmar is the United States, which has contributed $17 million in 2023 and more than $400 million in total since the Rohingya massacre in August 2017. The U.S. is followed by the European Union, which has contributed €24 million in 2023 and a total of €340.5 million since 1994.cxv Other international donors have also contributed to humanitarian support in Myanmar. For example, Japan has contributed $47 million since the coup.cxvi Canada has dedicated CAD$288.3 million for Myanmar and Bangladesh (for the displaced Rohingya) between 2021 and 2024.cxvii

Unfortunately, the international humanitarian aid response has been drastically short when compared with the need for an entire nation in a civil war and suffering mass displacement. For example, donor funding for Rohingya living in exile in Bangladesh fell from $12 per month in rations in 2022 to $8 per month 2023, which equates to just 27 cents per day.cxviii This has resulted in severe ration cuts from the World Food Program amid an already-malnourished community.cxix

Military Cooperation

The international community’s actions have been varied in terms of military responses. While there has been widespread condemnation of Myanmar’s military for the latter’s brutal crackdown on civilian protesters, some countries have continued to support Myanmar’s military by supplying arms and ammunition.

Within months of the coup and subsequent violent crackdown of civilian protesters, the U.N. Security Council called for an arms embargo on Myanmar.cxx However, only a nonbinding resolution was passed in the General Assembly, where 119 member states voted for the resolution and 36 abstained from it, including Russia and China.cxxi

The EU is among the few political entities that has imposed an arms embargo on Myanmar.cxxii Canada has an arms embargo in effect, including sanctions on aviation jet fuel to Myanmar’s military.cxxiii The Australian government also maintains an active arms embargo on Myanmar.cxxiv The U.S. and the U.K. have imposed targeted sanctions on specific entities in Myanmar, but not a total arms embargo.cxxv

At the same time, Myanmar’s military continues to have arms deals with China, Russia, India, Singapore, Thailand, and Israel. The U.N. Special Rapporteur to Myanmar exposed nearly $1 billion in the junta’s arms trades in a May 2023 report. It highlighted $406 million in arms deals with 28 suppliers in Russia, $267 million in deals with 41 suppliers in China, $254 million in deals with 138 suppliers in Singapore, $51 million in deals with 22 suppliers in India, and $28 million in deals with 25 suppliers in Thailand.cxxvi In addition, precision machines manufactured in Austria, Germany, Taiwan, Japan, and the U.S. are being used by Myanmar’s military to manufacture homemade weapons.cxxvii The Israeli arms maker CAA Industries was also found to be supplying firearm accessories.cxxviii

Political Actions

Immediately after the coup, the vast majority of the international community responded with strong verbal condemnation. Governments of the U.K., the U.S., the EU, Canada, Australia, Japan, and the like expressed strong disapproval of Myanmar’s military actions and called for the immediate release of detained civilian leaders.cxxix Later, in June of the same year, 119 countries voted for a U.N. General Assembly resolution condemning the junta.cxxx

Many countries – including the U.K., Denmark, Germany, Italy, and South Korea – have downgraded or are in the process of downgrading their diplomatic representations in Myanmar. Austria, Ireland, and Spain have not applied to accredit new envoys to their nonresident, Bangkok-based ambassadors to Myanmar. Among countries that belong to the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), Brunei and Malaysia have no ambassadors in Myanmar. The U.S. and Japan have maintained their embassies, while the embassies of India, China, and Russia have openly expressed support for the regime.cxxxi

Western nations have maintained or increased new sanctions on Myanmar since the coup d’état. The sanctions have come in the form of asset freezes, travel bans, trade restrictions, and financial measures targeting Burmese military officials and their businesses. As of July 2023, the EU imposed its seventh round of sanctions on Myanmar, bringing the total of its restrictive measures to 99 individuals and 19 entities.cxxxii Similarly, Canada’s last set of sanctions in January 2023 brought its cumulative list to 95 individuals and 63 entities, listed under “Special Economic Measures (Burma).”cxxxiii U.S. sanctions in March 2023 included prohibition of jet fuel provision to the Burmese military in addition to Business Advisory sanctions on a list of Burmese state-owned enterprises, gems and precious metals, real estate projects, and arms and military equipment categories.cxxxiv

The ASEAN’s initial response to the war in Myanmar has been that of noninterference. The ASEAN even invited the chief of Myanmar’s military, Senior General Min Aung Hlain, to its April 2021 summit to discuss its 5-point proposal for peace.cxxxv However, in the 2022 and 2023 summits, Myanmar was not invited because of its failure to implement the 5-point proposal.cxxxvi

Civil Society Responses

Civil society organizations all over the world mobilized to condemn the military coup and advocate for the restoration of civilian government. Protests were organized in major cities in the U.S.,cxxxvii Australia,cxxxviii Japan,cxxxix South Korea,cxl and the ASEAN members states.cxli People expressed their solidarity with protesters inside Myanmar, where organized groups from rival ethnicities showed unprecedented collaboration and solidarity for the first time in decades.cxlii Even the officially unrecognized and “despised” ethnicities, such as the Rohingya, were apologizedcxliii to and made welcome in the post-2021-coup uprisings of Myanmar.cxliv

Civil society actions included coordinated social media campaigns, which were instrumental in raising awareness about the coup and human rights violations in Myanmar. Hashtags such as #WhatsHappeningInMyanmar and #SaveMyanmar were widely used on Facebook and Twitter to draw global attention to the crisis and mobilize support.cxlv

International civil society organizations also provided support through global advocacy by engaging with policymakers in their respective countries of residence. This support was crucial in drawing the international community’s attention to divestments and targeted sanctions on Myanmar’s junta.cxlvi

In addition to advocacy, civil society organizations in neighboring states provided humanitarian support to refugees and displaced persons fleeing Myanmar. Karen refugees, in particular, were provided with shelter and legal support as they fled to Thailand across the border from Myanmar.cxlvii

Human rights monitoring groups like Amnesty International,cxlviii Fortify Rights,cxlix and Human Rights Watchcl have played major roles in highlighting human rights violations that have taken place since (as well as before) the February 2021 coup d’état. They produced detailed reports that documented extrajudicial killings by the junta, arbitrary arrests, and other human rights violations that could make valuable evidence for future accountability mechanisms.

Many international civil society organizations engaged with the United Nations’ Independent Investigative Mechanism for Myanmar,cli the Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar,clii the Special Advisory Council-Myanmar,cliii the International Criminal Court,cliv and the International Court of Justiceclv to open doors for prospective investigations into grave human rights violations committed by the military junta.

Responses to the Rohingya Crisis

The case of the Rohingya crisis in Myanmar is unique because it results from a conflict that is deeply rooted in religious and ethnocultural differences between the Rohingya and the rest of Myanmar. The Rohingya, a Muslim minority in a country with a Buddhist majority, have been subjected to systemic discrimination, apartheid, and denial of fundamental freedoms for more than half a century.clvi They are the largest minority that is not recognized by their name among the list of 135 officially recognized minorities in Myanmar.clvii In fact, they have been referred to as “kalar,” a derogatory term used to describe people of darker skin color, as “dogs,” and as “insects” in the years preceding their massacre in 2017.clviii

The 2017 massacre received coverage in social media as well as some attention in international news. Cellphone videos of burning villages and the subsequent exodus were widely circulated on social media.clix Survivor testimonies and interviews were shared by major news outlets worldwide.clx However, coverage slowed down as years passed, and other “newsworthy events” captured public attention. The 2021 coup d’état in Myanmar took the international focus away from the Rohingya to Myanmar’s public in general. And the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine took away the attention from Myanmar as well.

The Rohingya have no source of economic assistance from local or foreign entities. Economic activity has become more and more restrictive for the Rohingya in Myanmar ever since their citizenship rights were revoked in 1982. They are often subjected to arbitrary confiscation of land and crops by the Myanmar government’s forces. They are not allowed to move freely from one village to another. Even their access to education and healthcare is limited.clxi The Rohingya living in the refugee camps of Bangladesh are also not allowed to work legally. They are prohibited from obtaining formal education as well.clxii

Unlike other ethnic minorities of Myanmar – such as the Arakanese, Kachin, Karen, Chin, and Shan – the Rohingya do not have an organized self-defense force that could qualify to receive assistance from a foreign entity. The armed forces of ethnic groups in Myanmar serve as the primary force of protection from and deterrence to the aggressions by the ruling junta.clxiii In the absence of such a force, the Rohingya succumbed to the massacres of 1978, 1991, 2012, 2016, and 2017;clxiv and they continue to remain vulnerable to all kinds of human rights abuses and additional campaigns of massacres. Furthermore, they are unable to contribute to the current nationwide arms struggle against the junta, whereby a large number of ethnic armed groups are working collectively with the People’s Defense Force of the National Unity Government in exile.clxv This serves as a major disadvantage for the Rohingya when faced with the question of “what do you bring to the table?” in the nationwide struggle against junta rule.

In the aftermath of the 2017 massacre, the international humanitarian community made a generous response to the Rohingya. NGOs from all over the world came to help survivors in the refugee camps in Bangladesh.clxvi However, the situation today is very different, as aid money gets gradually reduced due to competing demands from other global crises.clxvii In 2023 alone, the World Food Program’s rations to the Rohingya refugee camps in Bangladesh were reduced from $12 per person per month to $10 and then to just $8, which is less than 27 cents a day.clxviii At the same time, in Myanmar, providing humanitarian aid is an impossibility because the Myanmar authorities systematically block aid from reaching the Rohingya (and other vulnerable populations). In the internally displaced person (IDP) camps, where nearly one-third of the population lives, it is common for children to die from malnutrition and treatable diseases like diarrhea.clxix

The international community took political action in the aftermath of the Rohingya massacre of 2017. The violence was immediately denounced as genocide by many prominent human rights institutions, including the U.S. Holocaust Museum.clxx Later on, many heads of state and governments also declared the situation to be genocide, including France, in 2017;clxxi Canada, in 2018;clxxii and the U.S., in 2022.clxxiii In 2019 the International Court of Justice began its preliminary proceedings on the case of a breach of the Genocide Convention brought by the Gambia against Myanmar.clxxiv In 2021 Canada, the U.K., and the Netherlands expressed their interest to intervene in the case;clxxv France expressed its decision to intervene in 2023.clxxvi The International Criminal Court is still investigating the prosecution of Myanmar’s leadership for the crime of forced deportation into Bangladesh.clxxvii However, issues of funding and political will continue to remain a hindrance to progress.clxxviii

International civil society groups that do human rights monitoring have made considerable efforts to cover the Rohingya crisis. In 2016 and 2017, Human Rights Watch covered the extermination of villages using satellite imagery.clxxix Following that, numerous other reports were published by various other entities – including Amnesty International,clxxx Fortify Rights,clxxxi Médecins Sans Frontières,clxxxii and Save the Childrenclxxxiii – that described the horrors of the massacre through detailed accounts from survivors. These reports and testimonies catalyzed the international community’s interest to push for accountability efforts. However, they did little to ameliorate the actual conditions of life and day-to-day realities of the Rohingya themselves.

One such reality is human trafficking, which still remains an unresolved issue.clxxxiv With worsening conditions in Myanmar’s IDP camps and little to no hope in the Bangladeshi refugee camps,clxxxv many Rohingya fall prey to traps of human traffickers that lure them with promises of a better life in Malaysia.clxxxvi The traffickers take all the life savings of the victims and their families as travel fare through the Andaman Sea and the jungles of Thailand. Often, the trafficking boats never make it through Andaman Sea; the traffickers exhort money from their victimsclxxxvii and desert the boats after they are denied entry by the Thai or Malaysian navy, leaving the refugees on board to die of starvation or simply by drowning.clxxxviii If the boats ever make it to Malaysian shores, the refugees enter illegally and live without papers, thereby facing all kinds of discrimination and denial of basic services and rights in their new country.clxxxix

Analysis of the Discrepancy in International Responses for Ukraine Compared with Myanmar

The differences in the international community’s responses to the war in Ukraine to that in Myanmar are quite vast and apparent. What could be the possible explanations for such a huge discrepancy?

Looking back at the international media response, a simple Google search for “Ukraine” under the News tab compared with a search for “Myanmar” would show the sheer difference in output through numbers alone. A search for “Ukraine” yields 48.1 million results (36 seconds output), while a similar search for “Myanmar” yields only 169,000 results (36 seconds output). News on Myanmar sitting on Google’s search engine is nearly 300 times less than that on Ukraine.

This discrepancy in media coverage can be largely attributed to the media freedom and support for coverage of the war in Ukraine compared with the severe restriction and life/death danger of coverage of the war in Myanmar. Reporteurs Sans Frontiers ranks Ukraine as 79th out of 180 countries in their order of press freedom based on political, economic, legislative, social, and security indicators. On the contrary, Myanmar is ranked 173rd out of 180 – with a security indicator as 180 of 180 – making it not only among the worst 10 countries in the world for press freedom in general but also the worst country in life security for press personnel.cxc

From an economic perspective, the United States alone is responsible for nearly $26.6 billion in financial assistance only (i.e., it excludes another $50 billion in humanitarian and military aid) provided to Ukraine in the last 1.5 years since the war began.cxci On the contrary, Myanmar’s anticoup government in exile, also known as the National Unity Government, requested $525 million in humanitarian and nonlethal weapons aid in July 2023, which has yet to be approved.cxcii For economic aid provided to Ukraine from other nations, including the EU, there is no comparison with the situation in Myanmar. Myanmar’s civilian population is not able to receive any economic aid stimulus without going through the ruling military junta.

Compared with Myanmar or any other country in a war today, Ukraine has the advantage of sharing deep economic interests with the rest of Europe and North America. Ukraine is one of the largest grain-producing countries in the world. It shares borders with Poland, the Slovak Republic, Hungary, Romania, and the like, which makes it a close contender to become the next member of the EU. Future potential trade relations between EU and Ukraine could be one of the reasons why economic assistance makes up a significant part of the EU’s aid package and by extension, that of the U.S. as well.

Similarly, social interests or social ties also play an important role in nations’ biases. Ukraine has social ties with neighboring European states and is socially closer to them than is Myanmar, for comparison purposes. Christopher Blattman, an economist at the University of Chicago and the author of “Why We Fight: The Roots of War and the Paths to Peace,” expressed the same at an interview with NPR where he said that “generally speaking, it seems reasonable for any society to care more about conflicts that are geographically closer, share a social identity.”cxciii

For humanitarian aid, the top donors, the U.S. and the EU, can be contrasted for the cases of Myanmar and Ukraine as follows. The EU website states that €24.5 million was provided to Myanmar in 2023.cxciv In contrast, €670 million plus €17 billion were provided to Ukraine as EU civil protection mechanisms and as support for refugees within the EU, respectively.cxcv The U.S. itself has provided nearly $4 billion to Ukraine in humanitarian aid alone.cxcvi In contrast, its aid for Myanmar stands at approximately $220 million in 2022, and $141 million thus far in 2023.cxcvii The U.N.’s Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Activities demonstrates how Country-Based Pooled Funds have been allocated from donors to recipients worldwide. Ukraine stands as the 3rd-largest recipient, with $82 million, while Myanmar stands as the 11th-largest recipient, with $28 million.cxcviii

This vast discrepancy in humanitarian aid can be attributed to the scale of mass displacement of Ukrainians versus that of Burmese. The UNHCR records 7.1 million Ukrainian refugees worldwide,cxcix while for Myanmar it records 1.3 million refugees and asylum seekers, and 1.5 million IDPs.cc Another reason for the discrepancy could be the resistance to aid in Myanmar compared with Ukraine. In Myanmar, aid is known to be systematically blocked and hijacked by the military regime,cci which naturally discourages donor countries from committing anything significant within Myanmar. Outside Myanmar, this argument does not hold true. The international community can very well support refugees in Thailand and Bangladesh. Unfortunately, both places are severely underfunded, and that speaks volumes about the double standards of donor nations when it comes to humanitarian aid.

Military aid to Ukraine from the United States alone has surpassed aid to any other nation in recent history. For $46.6 billion in military aid, as part of $76.8 billion in total aid to date, Ukraine received nearly 20 times more assistance than Afghanistan or Israel did in 2020.ccii In Myanmar, setting aside military assistance to the oppressor – i.e., the military junta – the civilian government in exile has yet to see any form of military aid from the international community. The National Unity Government has asked for $200 million in nonlethal funding from the United States, whose outcome is yet to be seen.cciii

The prime reason for the discrepancy explained above is geopolitical interest. Ukraine’s adversary is Russia – i.e., the former USSR, the archrival of the U.S. and Western Europe during the Cold War era, and the post–Cold War period. An invaded Ukraine where the rest of Europe failed would be analogous to an invaded Poland in the precursor to World War II. On the contrary, the People’s Defense Forces, which is the fighting arm of the civilian government in exile (i.e., the National Unity Government), does not present the same historical precedence as an invaded Poland in Eastern Europe does, for it to provide an equivalent impetus for Western powers to intervene with arms support.

In terms of the international community’s political responses through condemnation, both Myanmar and Ukraine received fairly widespread support from the rest of the world. However, putting the condemnation into action through political tools such as sanctions is where the real contrast between Ukraine and Myanmar can be seen. In Myanmar, the EU has implemented 7 rounds of sanctions or restrictions since 2018. The latest set of these restrictions that came to effect in July 2023 brought the total number of sanctioned individuals and entities in Myanmar to 99 and 19, respectively.cciv The sanctions applied to 7 thematic restrictions: arms exporting, asset freezing, dual-use goods exporting, restrictions on admission, restrictions on equipment for internal repression, telecom equipment, and restrictions on military training and cooperation.ccv For the war in Ukraine, the EU has imposed 11 rounds of sanctions on Russia since 2014. The last round of sanctions was passed in July 2023, bringing the total number of restricted individuals and entities to more than 1,800.ccvi The sanctions applied to 21 thematic restrictions in addition to nearly 20 different financial measures.ccvii The discrepancies are very obvious.

The incomparably high number of sanctions on Russia can be attributed again to geopolitics and history: it is the United States’ and the EU’s attempt to deter its archrival, the former USSR, from continuing a war in Europe. Cutting off an adversary’s financial sources is a decisive tactic in all wartime or proxy-war situations. With some foresight and political will, the same can be applied to the situation of Myanmar, seeing China, the primary power backing the junta, as the next archrival to the U.S.-led world order.

The international legal system is another area where discrepancies have become very apparent. In March 2023, the International Criminal Court’s Pre-Trial Chamber issued arrest warrants for Vladimir Putin and Maria Lvova-Belova for the unlawful deportation and transfer of Ukrainian children from occupied areas of Ukraine to the Russian Federation.ccviii These arrest warrants came just within a year of the Russian invasion operation. On the contrary, 6 years have passed since the last Rohingya massacre, and more than 10 years have lapsed since the extermination of entire villages surrounding Sittwe in northwestern Myanmar, where an unknown number of Rohingya, including children, were killed, burned, or sent to IDP camps.ccix The amount of evidence is overwhelming against Myanmar’s authorities responsible for crime of deportation, war crimes, and crimes against humanity,ccx as highlighted in the U.N.’s Fact Finding Mission on Myanmar’s report of 2018.ccxi The double standards as well as the dollar-driven justice practiced at the International Criminal Court is quite crystal clear.

International civil society responses also demonstrate a stark contrast for Ukraine compared with Myanmar. For example, most countries in Europe have civil societies that have welcomed and settled 5.8 million Ukrainian refugees,ccxii with Germany, Poland, and the Czech Republic taking nearly 3 million only among themselves.ccxiii Outside Europe, the United States has welcomed nearly 221,000 Ukrainian refugees since the outbreak of the war,ccxiv and Canada has welcomed nearly 175,000 thus far.ccxv Compare these with the numbers for Myanmar; the vast majority of Burmese refugees in neighboring states are approximately 920,000 in Bangladesh,ccxvi and 90,000 in Thailand.ccxvii For refugees outside Myanmar, the United States welcomed 2,100 Burmese refugees in 2022.ccxviii The vast majority of Burmese refugees live in IDP camps inside Myanmar; in 2022 alone, 1.2 million people became refugees inside Myanmar.ccxix Refugees from Myanmar take great risks to get out of the country, including embarking on dangerous human trafficking boats in hopes of finding better life elsewhere in Southeast Asia.ccxx Many of them never see their hopes fulfilled as they perish in the seas.ccxxi

The situation described above is another example of the international community’s double standards on human rights and humanitarianism. Despite all the geopolitical and socioeconomic reasoning behind the international bias for Ukraine, the justifications hold no bearing from a human rights standpoint. Geopolitics aside and socioeconomic interests aside, it would be indefensible in any human rationale to say that Ukrainian lives are more precious than Burmese lives or that Burmese are less human than Ukrainians. From both monetary and political viewpoints, the humanitarian and refugee resettlement support provided to Myanmar is miniscule compared with what is provided to Ukraine. The number of refugees in Ukraine may be larger than that in Myanmar; however, that does not imply that Myanmar’s refugees need to be ignored, so much that they perish in human trafficking boats in the Indian Ocean. Or this does not imply that people in refugee camps have their World Food Program rations reduced to 27 cents a day due to funding shortages.ccxxii

Bringing awareness to underreported wars and crises is a major challenge that we face today, according to CARE, as detailed in the international aid group’s 2021 publication “‘Breaking the Silence’: The Most Under-Reported Humanitarian Crises.”ccxxiii Media organizations naturally play a role in deciding whether to allocate time and resources to underreported wars and crises. However, this may not be an easy task in situations where there is a lack of financial resources or political will to cover crises in regions of the world that the audience of the broadcasting entity does not necessarily care for. This is even more true for a media that is heavily guided by advertising revenue, politics, and public perceptions.

Nevertheless, even with coverage, other factors come to play. At the 2022 Pearson Global Forum at the University of Chicago, panelists discussed the bias in coverage of the Ukraine conflict. A Reuters journalist at the forum expressed it this way: “You see a lot of journalists, whether they be from Ukraine, the U.S. or from Europe, who are extremely empathetic. They’re embedded with Ukrainian troops. They’re even covering Ukrainian drone strikes on Russian positions with a lot of support and a lot of empathy. Can you imagine CNN embedding with Palestinian resistance fighters in Israel, fighting against Israeli occupation? Both of those situations are essentially the same, and I think that has raised questions.”ccxxiv

In some instances, biases have been overtly, and condescendingly, expressed. A couple of well-known examples are CBS correspondent Charlie D’Agata’s remarks, where he said “this isn’t a place, with all due respect, you know, like Iraq or Afghanistan that has seen conflict raging for decades. … You know, this is a relatively civilized, relatively European, … city.ccxxv” In another example, ITV News correspondent Lucy Watson said the “unthinkable” had happened, adding “this is not a developing third-world nation, this is Europe.” Many other examples are out there, including one that mentions “European people with blue eyes and blonde hair are being killed.”ccxxvi Such attitudes are at the core of inherent biases in the international community’s responses. They do not exclusively limit themselves to the media, but they also manifest in the attitudes of the public, and their subsequent support for policymakers’ decisions. Take, for example, how Europeans complained about the influx of Syrian refugees fleeing Bashar al Assad, or of migrant boats crossing the Mediterranean to seek asylum in Europe. Contrast that with the swift acceptance of Ukrainian refugees all around Europe within months if not weeks of the onset of the Russian invasion. Such behaviors are inherently racist in nature; they tarnish human rights with an idea of hierarchy, whereby some groups of individuals merit peace and safety while others do not.ccxxvii

Policy Recommendations

The international responses to the conflict in Ukraine compared with that in Myanmar speak openly of the double standards of the media, business, and politics when it comes to humanity and human rights. The vast proportion of the international responses to these two conflicts is constituted by wealthy nations that are under the influence of the U.S.-led world order. The responses to the conflicts by the U.K., EU, Canada, Australia, Japan, South Korea, the Gulf Cooperation Council nations, and all other close allies of the West have been nothing short of preferred favoritism toward Ukraine compared with responses to other nations in conflict elsewhere in the world. If you desire to win a share of the U.S.-led world order, then you had better religiously support Ukraine against Russian invasion, even on a smaller scale. The favoritism and double standard of human rights almost have “no escape.”

Unfortunately, there is not a lot that one can do in the face of such favoritism and double standards. The forces of geopolitical and economic interests of the West in Ukraine are too powerful to sway things in any other direction. Money and power will always have the upper hand in human history.

These attitudes of blind favoritism, however, have the potential to change if a situation arises where there is a shift in geopolitical and economic interests toward Southeast Asia. And such a situation is not far from the near future – in only a matter of time, U.S. and EU policymakers will become aware that losing interest in Myanmar will equate to losing the second-largest country in Southeast Asia, and subsequently other countries in the region, to full Chinese influence. Providing support to Myanmar has the potential to yield vast economic benefits to the West through Myanmar’s rich resources, including oil and natural gas, precious mineral reserves, human resources, and giant consumer markets. It also has the potential to yield increased access to the Bay of Bengal and Andaman Sea for trade and naval forces presence.

However, until there is a serious shift in political and economic attention to Southeast Asia, here are policy recommendations that the U.S., EU, and other players in the international community should consider to address the conflict in Myanmar, including the Rohingya crisis:

- The U.S., U.K., and their allies should impose comprehensive arms embargoes on Myanmar, as the EU has done (seeing that the same cannot be done through the U.N. Security Council).

- The U.S., U.K., EU, and their allies should sanction Myanmar Oil and Gas Enterprise, the largest source of revenue for the military junta.

- The U.S., U.K., and EU should impose secondary or extraterritorial sanctions on Thai, Singaporean, Japanese, Indian, and other national entities that continue to do business with Myanmar.

- The U.S., U.K., EU, and their allies should restrict trading and payment system platforms that Myanmar’s junta utilizes for its business dealings (which may not work for dealings in Chinese-based platforms).

- The ASEAN should play a larger role in Myanmar than simply putting forward a 5-point consensus peace proposal; it should reject the illegitimate junta government and set forth a proper effort to bring back democracy in Myanmar that is inclusive of all ethnic minorities. It should conduct a full investigation of war crimes and crimes against humanity committed by the junta.

- The ASEAN should impose penalties on its member states that continue to do business with Myanmar, despite the latter’s refusal to accept the ASEAN’s 5-point consensus proposal.

- If the ASEAN is to ever accept the junta government and allow its member states to conduct business with the junta, then it should stipulate these conditions for Myanmar: unfettered access for aid workers, journalists, and peacekeepers; dismantling IDP camps; release of political prisoners; and guaranteed return with full rights and protections for the Rohingya and other displaced minorities.

- The U.S., the EU, and their allies, as well as the ASEAN, should invest in media organizations and reporting agencies that work on covering what is happening in Myanmar and should ensure that this coverage continues without fail.

- The IMF and World Bank should provide incentives to Bangladesh so that the latter allows the Rohingya to obtain education and subsequently find work in the Cox Bazar / Teknaf region. That way, the Rohingya can contribute to the Bangladeshi economy instead of becoming a burden.

- Canada, the U.K., and the Netherlands have expressed their intention to intervene in the International Court of of Justice’s case of the Gambia versus Myanmar by becoming a party to the case; they should fulfill their intention and help the case continue.

- The International Criminal Court’s case on the crime of forced deportation to Bangladesh has not yet started its proceedings, even though it has been six years since the 2017 Rohingya massacre. The Court should immediately begin its proceedings on the forced displacement of the Rohingya.

- The U.N. and its member states should ensure that the refugee camps in Bangladesh and the IDP camps in Myanmar have at least sufficient food and basic necessities to survive; no one should struggle for food in this day and age due to a lack of funding.

- The U.N. should create conditions that discourage human trafficking through the Andaman Sea: improve living conditions in the refugee camps in Bangladesh, and provide incentives to the Bangladeshi government to allow education and economic opportunities for refugees in the camps.

- The U.S. recognized the Rohingya genocide in 2022; however, it has not taken actions commensurate with this recognition. The U.S. government can and should utilize its economic, political, and military presence in the region to prevent further aggravation of the situation of the Rohingya in Myanmar and Bangladesh.

- The U.S. and its allies should collectively propose an unbiased, Rohingya community-led repatriation plan that calls for refugees to return to their homelands with full citizenship rights and international protection. Several other countries have proposed repatriation plans; the U.S. and its allies should have their own proposal.

- The U.S., U.K., EU, Canada, and Australia can bring Rohingya youths to their respective countries through scholarship programs and vocational training programs with paid contracts for them to return back to Bangladesh/Myanmar and work for international NGOs on the ground.

- The U.S., U.K., EU, Canada, and Australia can train a group of Rohingya doctors, nurses, teachers, journalists, lawyers, law enforcers, entrepreneurs, public administrators, technicians, and technologists so that they contribute to building Myanmar when they eventually return to their homelands.

- The Organization of the Islamic Cooperation and its member states can assist with the development of a Rohingya defense force that can join hands with People’s Defense Forces and make a Rohingya contribution to the collective struggle for freedom from junta rule in Myanmar.

- If there is a scenario of another imminent large-scale massacre by the junta, the U.S. and its allies should push for the provision of a peacekeeping coalition force, such as the International Security Assistance Force in Afghanistan.

At the very least, speaking about the conflict in Myanmar, and the international favoritism toward some countries and neglect to others, will help bring attention to topics like Myanmar. And it will also help bring attention to Ethiopia, Yemen, Palestine, Syria, and other war-torn countries. Even momentary coverage of Myanmar in between endless coverage of what is happening in Ukraine is better than no coverage at all.

When we focus almost exclusively on one conflict and turn a blind eye to another one, the end result could be severely catastrophic. History has shown us examples: The focus on the Balkans with a blind eye toward Rwanda resulted in 800,000 people being massacred in 40 days, in what we now know as the Rwandan genocide. And the excessive focus on the post-9/11 war in Afghanistan and turning a blind eye toward Sudan resulted in 200,000 dead, in what we now know as the Darfur genocide.

The case of Myanmar is not far from these earlier examples of genocide. Myanmar already has seen its genocide, in 2017, when it conducted a state-led Clearance Operation in an attempt to exterminate the Rohingya. Nearly 400 of the 800 Rohingya villages were wiped from Myanmar’s map, and approximately 750,000 refugees fled to refugee camps in Bangladesh, with harrowing accounts heard from survivors of gang rapes, live burning, and scorched earth practices. It will not take a lot for Myanmar’s ruling junta to repeat a similar operation to exterminate the remaining Rohingya – or any of the other ethnicities – while the rest of the world remains focused almost exclusively on the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Endnotes

1 Statista. (2023). Total bilateral aid to Ukraine by country & type 2023. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1303432/total-bilateral-aid-toukraine/.

2 Conflict. In Cambridge Dictionary. Cambridge University Press. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/conflict.

3 Conflict. In Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/conflict

4 International. In Cambridge Dictionary. Cambridge University Press. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/international.

5 International. (2023). Merriam-Webster Dictionary, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/international.

6 Response. In Cambridge Dictionary. Cambridge University Press. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/response.

7 Response. (2023). In Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/response.

8 NBC News. (2014, March 18). Crimea Was ‘Stolen’ From Russia, Vladimir Putin Says. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/storyline/ukraine-crisis/

crimea-was-stolen-russia-vladimir-putin-says-n55366.

9 Center for Preventive Action. (2023). War in Ukraine, Global Conflict Tracker. Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/global-conflicttracker/conflict/conflict-ukraine.

10 BBC. (2023, September 8). Ukraine in maps: Tracking the war with Russia. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-60506682.

11 Financial Times. (2023, September 13). Ukraine’s counteroffensive against Russia in maps: latest updates. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/

content/4351d5b0-0888-4b47-9368-6bc4dfbccbf5.

12 Buchholz, K. (2023). Infographic: Ukrainians’ Desire to Join NATO and the EU. Statista. https://www.statista.com/chart/26933/ukrainians-surveynato-eu/.

13 Burdeau, C. (2022, May 9). Putin blames NATO for pushing Russia into invasion. Courthouse News Service. https://www.courthousenews.com/putinblames-nato-for-pushing-russia-into-invasion/

14 Amar, F. Ukraine: Civilian casualties from 1 to 16 July 2023. OHCHR. https://www.ohchr.org/en/news/2023/07/ukraine-civilian-casualties-1-16-

july-2023.

15 Faulconbridge, G. (2023, April 12). Ukraine war, already with up to 354000 casualties, likely to last past 2023: U.S. documents. Reuters. https://www.

reuters.com/world/europe/ukraine-war-already-with-up-354000-casualties-likely-drag-us-documents-2023-04-12/.

16 Davies, E., Birsel, R., & Pullin, R. (2021, January 31). Explainer: Crisis in Myanmar after army alleges election fraud. Reuters. https://www.reuters.

com/article/us-myanmar-politics-explainer-idUSKBN2A113H.

17 Adams, B. (2022). Myanmar: Year of Brutality in Coup’s Wake. Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/01/28/myanmar-yearbrutality-coups-wake.

18 Hein, Y. M. (2022). Understanding the People’s Defense Forces in Myanmar. United States Institute of Peace. https://www.usip.org/

publications/2022/11/understanding-peoples-defense-forces-myanmar.

19 Maizland, L., Kurlantzick, J., & McGowan, A. (2022). Myanmar’s Troubled History: Coups, Military Rule, and Ethnic Conflict. Council on Foreign

Relations. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/myanmar-history-coup-military-rule-ethnic-conflict-rohingya.

20 ACLED. Dashboard; ACLED. https://acleddata.com/dashboard/#/dashboard.

21 Roth, K. World Report 2022: Myanmar. Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2022/country-chapters/myanmar.

22 Fletcher, R. (2022, June 15). Perceptions of media coverage of the war in Ukraine. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. https://

reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/digital-news-report/2022/perceptions-media-coverage-war-Ukraine.

23 Fisher, H. O. (2023). Media Objectivity and Bias in Western Coverage of the Russian-Ukrainian Conflict.

24 De Boer, L. (2023). Disinformation in a Time of War: A Critical Discourse Analysis of Russian Disinformation Strategies During the Russo-Ukrainian

War of 2022.

25 Shen, F., Zhang, E., Zhang, H., Ren, W., Jia, Q., & He, Y. Examining the differences between human and bot social media accounts: A case study of the

Russia-Ukraine War. First Monday, 28(2). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v28i2.12777.

26 International Monetary Fund (2023). The IMF Board approved a new 48-month extended arrangement under the Extended Fund Facility (EFF) of

SDR 11.6 billion (about US$15.6 billion) as part of a US$115 billion total support package for Ukraine. International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.

org/en/News/Articles/2023/03/31/pr23101-ukraine-imf-executive-board-approves-usd-billion-new-eff-part-of-overall-support-package.

27 World Bank. (2023, June 29). World Bank’s New $1.5 Billion Loan to Ukraine Will Provide Relief to Households, Mitigate Impacts of Russia’s Invasion.

World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2023/06/29/world-bank-new-1-5-billion-loan-to-ukraine-will-provide-relief-tohouseholds-mitigate-impacts-of-russian-invasion.

28 Sconosciuto, L. (2023). EBRD and the Netherlands cooperate to support Ukraine. European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD).

https://www.ebrd.com/news/2023/ebrd-and-the-netherlands-cooperate-to-support-ukraine-.html.

29 Statista. (2023). Total bilateral aid to Ukraine by country & type 2023. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1303432/total-bilateral-aid-toukraine/.

30 Statista. (2023). Total bilateral aid to Ukraine by country & type 2023. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1303432/total-bilateral-aid-toukraine/.

31 Djurica, M., & McGowan, A. (2023). How Much Aid Has the U.S. Sent Ukraine? Here Are Six Charts. Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.

org/article/how-much-aid-has-us-sent-ukraine-here-are-six-charts.

32 Statista. (2023). Total bilateral aid to Ukraine by country & type 2023. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1303432/total-bilateral-aid-toukraine/.

33 Matisek, J. (2023). The Good, the Bad and the Ugly: Assessing a Year of Military Aid to Ukraine. RUSI. https://www.rusi.org/explore-our-research/

publications/commentary/good-bad-and-ugly-assessing-year-military-aid-ukraine.

34 NATO. (2023). NATO’s military presence in the east of the Alliance. NATO. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_136388.htm.

35 United Nations Foundation. (2023). How the U.N. Is Supporting the People of Ukraine. United Nations Foundation. https://unfoundation.org/ukraine/.

36 United Nations Foundation. (2023). How the U.N. Is Supporting the People of Ukraine. United Nations Foundation. https://unfoundation.org/ukraine/.

37 American Red Cross. (2022). In Ukraine, Red Cross Partnership Delivers Critical Food Aid. American Red Cross. https://www.redcross.org/about-us/

news-and-events/news/2022/in-ukraine-red-cross-partnership-delivers-critical-food-aid.html.

38 Charity Intelligence Canada. (2022). How the Red Cross is spending money in Ukraine. Charity Intelligence. https://www.charityintelligence.ca/

research-and-news/ci-views/31-disaster-response/708-an-update-on-red-cross-work-in-ukraine.

39 Swaton, C. (2023). Austrian president promises Ukraine further aid. EURACTIV.com. https://www.euractiv.com/section/politics/news/austrianpresident-promises-ukraine-further-aid/

40 Willems, A., Cardoen, S. (2022). “Wereld belooft 10,1 miljard euro aan Oekraïne, België trekt 800 miljoen euro uit: waar gaat dat geld naartoe? Vrtnws.

https://www.vrt.be/vrtnws/nl/2022/04/09/donoractie-in-warschau-voor-oekraine/.

41 “Canada completes issuance of $500 million Ukraine Sovereignty Bond.” 2022. https://www.canada.ca/en/department-finance/news/2022/11/canadacompletes-issuance-of-500-million-ukraine-sovereignty-bond.html

42 Department of Finance, Canada. (2023). Ministeren for udviklingssamarbejde og global klimapolitik besøger Mykolaiv i Ukraine, Udenrigsministeriet.

https://via.ritzau.dk/pressemeddelelse/ministeren-for-udviklingssamarbejde-og-global-klimapolitik-besoger-mykolaiv-i-ukraine?publisherId=201266

2&releaseId=13668477.

43 BNS. (2022). Lithuania’s support to Ukraine totals €660m. Lrt.lt. https://www.lrt.lt/en/news-in-english/19/1838101/lithuania-s-support-to-ukrainetotals-eur660m.

44 Rijksoverheid. (2023). Kabinet maakt tweede steunpakket Oekraïne en nieuwe Oekraïne-gezant bekend. Rijksoverheid. https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/

actueel/nieuws/2023/07/4/kabinet-maakt-tweede-steunpakket-oekraine-en-nieuwe-oekraine-gezant-bekend.

45 Rijksoverheid. (2023). Kabinet maakt tweede steunpakket Oekraïne en nieuwe Oekraïne-gezant bekend. Rijksoverheid. https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/

actueel/nieuws/2023/07/4/kabinet-maakt-tweede-steunpakket-oekraine-en-nieuwe-oekraine-gezant-bekend.

46 Hussein, M. (2023). Qatar to provide Ukraine with $100m in humanitarian aid: Kyiv. Middle East Monitor. https://www.middleeastmonitor.

com/20230728-qatar-to-provide-ukraine-with-100m-in-humanitarian-aid-kyiv/

47 Kyiv Independent. (2022). Saudi Arabia to provide $400 million in humanitarian aid to Ukraine. Kyiv Independent. https://kyivindependent.com/

saudi-arabia-to-provide-400-million-in-humanitarian-aid-to-ukraine/.

48 Government of the Republic of Korea. (2022). Korea to Send Humanitarian Aid to Ukraine: Ukraine. Reliefweb. https://reliefweb.int/report/ukraine/

korea-send-humanitarian-aid-ukraine.

49 Ministry of Foreign Affairs, South Korea. (2023). MOFA Spokesperson’s Statement on 1-Year Mark of Ukrainian War View. Ministry of Foreign Affairs,

South Korea. https://www.mofa.go.kr/eng/brd/m_5676/view.do?seq=322155

50 Statista. (2023). Total bilateral aid to Ukraine by country & type 2023. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1303432/total-bilateral-aid-toukraine/.

51 Statista. (2023). Total bilateral aid to Ukraine by country & type 2023. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1303432/total-bilateral-aid-toukraine/.

52 European Council. (2023). EU response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. European Council. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/eu-responseukraine-invasion/.

53 Schneider, E., & Guterres, A. (2022, March 2). General Assembly resolution demands end to Russian offensive in Ukraine. UN News. https://news.un.org/

en/story/2022/03/1113152.

54 United Nations. (2022, October 12). With 143 Votes in Favour, 5 Against, General Assembly Adopts Resolution Condemning Russian Federation’s

Annexation of Four Eastern Ukraine Regions. October 12, 2022. https://press.un.org/en/2022/ga12458.doc.htm

55 Hürriyet Daily News. (2022). Türkiye hopeful for truce between Ukraine-Russia, Erdoğan says. Hürriyet Daily News. https://www.hurriyetdailynews.

com/erdogan-to-discuss-nato-bid-with-swedish-pm-in-turkiye-177883.

56 ABC News. (2022, February 28). Ukraine and Russia complete first round of peace talks at Belarusian border. ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/

news/2022-02-28/ukraine-russia-peace-talks-belarus-border/100869782.

57 Euronews. (2023, April 8). Ukraine urged to give up Crimea by Brazil’s Lula. Euronews. https://www.euronews.com/2023/04/07/the-world-needstranquillity-ukraine-urged-to-give-up-crimea-by-brazils-lula.

58 Turak, N. (2023, August 1). Saudi Arabia and Turkey are emerging as the new peace brokers of the Russia-Ukraine war. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.

com/2023/08/02/saudi-arabia-and-turkey-the-new-peace-brokers-of-russia-ukraine-war.html.

59 Lau, S., von der Burchard, H., & Bayer, L. (2023). China talks ‘peace,’ woos Europe and trashes Biden in Munich. Politico. https://www.politico.eu/

article/china-wang-yi-peace-europe-joe-biden-munich-security-conference/

60 Connolly, N. (2023, June 18). African delegation in Eastern Europe: More than a photo op?. Deutsche Welle. https://www.dw.com/en/africandelegation-in-eastern-europe-more-than-a-photo-op/a-65954255.