Read the Essay Here

Abstract

Every day, people in different parts of the world are facing different forms of violence, repression, and ethnic cleansing, often giving rise to genocide. This has led to a growth in the global refugee population. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the number of refugees worldwide has increased by 12.7 million in the last 32 years (from 19.8 million in 1990 to 32.5 million in 2022).i On the other hand, a total of 103 million people are currently spending their lives as forcibly displaced in different parts of the world.ii Women and children constitute the majority of these people and become the worst victims of persecution.iii Despite these striking statistical evidences, global funding for refugee protection has significantly decreased.iv The shifting dynamics of displacement and the plight of refugees demand critical insights into the concept of refugeehood that look beyond the political connotations and include socioeconomic aspects, i.e., stigma, discrimination, and racialization. Similarly, the humanitarian responses to refugees need to be critically evaluated.

Against this backdrop, this paper considers the case of the Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh and examines the responses of national, regional, and global actors through qualitative research. For the purpose of this research, the paper takes into account the period since responses to the Rohingya crisis have become institutionalized, from the 1990s until today. It examines the nature of the responses; the changes, if any, that have occurred over the time; and, more critically, the limits of humanitarian responses. The research looks at the intersectional and intergenerational dimensions of refugee camps’ populations, which include women, children including orphan children, the elderly, and people with special needs. The inclusivity and specificity of the interventions, therefore, are important. The study considers the responses from state/government organizations (GOs), nongovernmental 0rganizations (NGOs), and intergovernmental organizations (IGOs), which have roles to play in providing humanitarian responses to the Rohingya refugees.

- Introduction

Human mobility and displacement have been occurring since the dawn of civilization. Unfortunately, two world wars and the subsequent development of institutional norms could not reduce the plight of people as consequences of persecution, genocide, mass violence, and both interstate and intrastate conflicts. Between the 1990s and 2020s, the number of refugees almost doubled, reaching 35.3 million in 2023.v It is to be noted that some groups among the refugees are more vulnerable than others due to their socioeconomic positions. These include women, children, people of color, and disabled populations. Women and children constitute the highest portion of refugees worldwide. There are also different communities whose members are not considered refugees but are either stateless or asylum seekers. Currently, there are 5.2 million asylum seekers, 4.4 million stateless people, and 5.2 million people in need of international protection.vi

The Rohingyas are one of those groups of stateless people who have been persecuted for generations in their own country. Their history of persecution has largely been overlooked by the international community. The 2017 genocide was one of the most vicious incidents in recent history, and it produced the highest number of refugees in Asia after the Vietnam War.vii According to UNHCR, an estimated 1.1 million Rohingyas have taken shelter in the southeastern border area of Bangladesh. And this number is even increasing within the area’s limited space as more and more refugee children are born every month. These people are not only being stripped of their basic rights of citizenship by the Myanmar state authorities but are also dependent on funding and assistance from the Government of Bangladesh and international donor organizations. Nevertheless, the declining trend of donations and of funding for refugees worldwide, including the Rohingyas, has engendered a new form of uncertainty that needs cautious analysis.

With this backdrop, this paper aims to examine the trends of humanitarian responses to the Rohingya crisis. For this study, the primary focus has been on the developments during and after the Rohingya influx in the 1990s, although significant incidents from the past have also been recorded and referred to where they are deemed to be required to put things in perspective. The paper argues that geopolitics and geoeconomics are increasingly becoming crucial drivers for humanitarian aid, refugees, and refugee-like situations. The paper is mainly based on secondary literature, including books and journal articles. Additionally, reports and statistics from different international and national organizations – i.e., the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) – have been used as primary documents. The paper is divided into five sections. After this brief introductory section, the second section discusses the evolution of international refugee protection programs and their patterns of responses to refugee crises over time. The third section gives an overview of the Rohingya crisis in Bangladesh. The fourth section evaluates and critiques the humanitarian responses to the Rohingya refugee crisis from 1992 to 2023. In this regard, it considers both intergenerational and intersectional responses, including those of transnational donor agencies, national protection measures, and initiatives undertaken by regional or subregional bodies. The paper ends with concluding remarks.

- The Evolution of Humanitarian Responses to Refugee Crises

The concepts of refugeehood and humanitarian aid are politically and historically embedded. Although the term “refugee” was institutionally established in 1951 through the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, people were refugees and humanitarian aid was given long before that. The English anthropologist Jonathan Benthall made a distinction between the modern and old period of humanitarian responses, namely, “before Dunant” and “after Dunant.” The latter signifies the establishment of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) in 1864viii, through the work of Henry Durant, about whom the ICRC has said: “[He was] the man whose vision led to the creation of the worldwide Red Cross and Red Crescent movement; he went from riches to rags but became joint recipient of the first Nobel Peace Prize.” However, it was Fridtjof Nansen whose appointment as the first high commissioner for Russian refugees after World War I led to significant developments in bringing together the issues of humanitarian assistance and refugee crises.ix Despite not having any specific agency dedicated to the protection and assistance for global refugees, Nansen expanded the existing protection mandate to Armenian (1924), Assyrian (1928), and Turkish refugees (1928).x

During this period, the League of Nations also took a groundbreaking step by ensuring de jure protection of people without a nationality through its general policies. The League’s Advisory Commission for Refugees pointed out in 1929 that the critical aspect of protection is to extend “no regular nationality and … deprived of the normal protection accorded to the regular citizens of a State.”xi The academic debates regarding the concept and status of refugees between 1920 and 1935 also helped U.N. bodies develop the first legal document on this issue in the 1950s.xii

Throughout these years, displacement-related assistance programs have been undertaken by organizations anchored in particular nation-states. Since 1863, the ICRC has primarily operated from Switzerland, and Save the Children began operating in 1919 from England. However, large-scale international and intergovernmental developments in this area did not begin until World War II. The war led to approximately 40 to 60 million refugeesxiii, which is the highest number until today, and this huge number required immediate legal, institutional, and humanitarian actions. Organizations like Oxfam (founded in 1942) and CARE (1945) had been working on these issues. After the creation of the U.N. in 1945, the existing humanitarian organizations expanded internationally and extensively. At the same time, newer organizations dedicated to humanitarian relief and protection were established. These included the U.N. Disaster Relief Office, the U.N. International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), the U.N. Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), and the World Health Organization (WHO), all of which were established in the 1970s.xiv

In the 1970s, refugee repatriation became a prominent issue. Feller called it the “decade of repatriation,” since a number of countries – Angola, Bangladesh, Guinea-Bissau, and Mozambique – demonstrated successful examples of repatriation of millions of refugees.xv During the late 1960s and 1970s, refugee protection programs also expanded regionally. Two of the notable examples are the 1969 Convention on the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa, or the Organization of African Unity Refugee Convention, and the 1979 International Conference on Refugees and Displaced Persons in Southeast Asia.

In the 1980s, the number of refugees started to increase, and support from local communities waned. Conversely, during this period the Cold War’s geopolitics found its way into the refugee crisis. Therefore, aid to refugees became an expansionist tool of the two superpowers, the U.S. and the USSR.xvi Scholars have also identified “policy convergence” between the U.S. and UNHCR through refugee aid, which helped the U.S. expand its bloc across the African region while influencing these colonies’ liberation movements.xvii In general, it turned into an effective instrument for Western countries to plunge into the Global South through legal and humanitarian activities, endorsed by U.N. resolutions and UNHCR’s mandates.xviii

One must take into account that the creation of international aid policy for refugees was not exclusively for refugees. Rather, it started as part of relief and development programs. It was the 1980s when refugee aid and development began to be adopted as a separate policy and was explicitly mentioned in policy papers.xix However, the trend of integrated resettlement programs to incorporate both refugee and host communities did start with the initiatives of the League of Nations, which eventually provided options for multistakeholder approaches. Notably, the International Labor Organization was largely involved in public projects and reconstruction/resettlement programs.xx The incorporation of refugees into development programs was also targeted as a makeshift policy for seeing refugees as moving from “masses of humanitarian need” to capable humans with specific skills.xxi

Post-Cold War civil wars resulted in an unmanageable number of refugees and stateless people all over the world. While the number of refugees in the late 1970s was only a few million, it went up to 10 million within a decade; and by the mid-1990s, the number escalated to about 25 million.xxii In 1978, Bangladesh also faced the first expulsion of Rohingya refugees from Burma (now Myanmar). The second influx took place in 1992. At the same time, the Iraq-Iran war, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and civil conflicts in Yugoslavia, Rwanda, and Bosnia led to enormous refugee inflows and outflows with almost no to little chance of repatriation. The sheer number and expanse of this refugee crisis compelled UNHCR to undertake prolonged programs. The traditional purpose of “temporary protection”xxiii of refugees hence became obsolete and required comprehensive engagement and financial aid. Czaika and Mayer have shown an interesting trend in donor countries’ refugee aid policies through their research that posits an idea that these countries are more interested in providing aid and assistance to cross-border refugees who might pose a direct or indirect risk to those states by their physical movements.xxiv In other words, these states, mainly Western, perceive a policy contradiction between “humanitarianism” and “national protection interest” that influences their decision-making process and volume of aid disbursement.xxv Gradually, in the 2000s, the broad umbrella of aid policy also changed from refugee aid and development to development assistance for refugees.

In the 2000s and 2010s, refugee problems became more sporadic, covering wide ranges of regions and more diverse issues than ever. Europe’s concerns with the refugee influx from the Middle East, particularly Syria, became one global highlight. Newfound concerns – including rape, sexual assault, human trafficking, climate-induced displacement, and women’s and children’s needs – became integral parts of refugee problems and needed specific attention from global protection programs. At the same time, UNHCR remained the core coordinating institution for resolving these issues, while depending on countries’ voluntary funding mechanisms. “Assistance” and “protection,” in this period, were complementary, as the U.N. agencies took into cognizance the basic needs of refugees (i.e., food, shelter, and health care), along with the protection mandatexxvi, which required further allocation of funds and the willingness of host countries to disburse and manage them properly.

Globally, there is a shortage of funding compared with the number of people being made refugees every day or at the brink of displacement. Refugees’ “degree of unwantedness,” therefore, may determine to what extent they are receiving support from a particular state. Investigating the trends in refugee protection and assistance in the 200os, Strang and Ager have noticed that there are subtle distinctions in funding allocations for refugees and asylum seekers.xxvii These distinctions primarily work based on black-and-white policy agendas, where citizens of the host countries are deemed “deserving” while the refugee population mainly comprises the “undeserving” group. The dwindling nature of funding from international actors and donors also helped states change their own policies negatively toward the refugees. Showing an example of Tanzania’s refugee situation, Whitaker has stated,

Funding cuts for the refugee operation in Tanzania provided government officials with an excuse for changing their policies. … Tanzanian officials had legitimate concerns with respect to regional security and the impact of the refugee presence on their own population. Given that the international community failed to adequately fund the refugee operation, and that many donor countries themselves were developing more restrictive immigration policies, the Tanzanian government was effectively shielded from international criticism for its new approach.xxviii

Strang and Ager maintain that Western countries’ “assimilation” or “integration” approach also shrunk due to economic, political, and security considerations. With reference to their arguments, one can easily discern that the priority group in this case was not the refugees, who would belong to “undeserving” groups. Thus, the post–World War II ethos of “international responsibility,” “burden-sharing,” and “responsibility of states”xxix gradually became more parochial and susceptible to national and regional security frameworks, and this trend still continues.

- The Rohingya Crisis: Background and Development

Possibly one of the highly overlooked refugee situations in the 21st century is the Rohingya crisis, which has been going on for about five decades. The Myanmar junta’s atrocities and genocidal acts against the Rohingya people due to their ethnic and religious status resulted in three major refugee influxes, in the 1970s, 1990s, and 2010s. Although a number of South Asian and Southeast Asian countries have been affected by these influxes, Bangladesh has been the primary receiving end, with millions of Rohingya refugees living in the country’s Cox’s Bazar and Bhasan Char regions. The country is also struggling due to the limited response from the international community – in diplomatic, political, and legal actions – coupled with the diminishing amount of funding from international donors.

Myanmar’s problems with the Rohingyas are not a stand-alone issue; rather, they are a consequence of the state’s failure to incorporate its highly heterogeneous and diverse ethnic groups into its administrative process over half a century. The “nationalist element” of Buddhism in Myanmar emerged during the country’s anticolonial movements against the British. However, it took a fascist turn when the military organized a revolution against the British and labeled the Rohingyas a hostile group because of their history of loyalty to the colonial power.xxx However, whether consciously or subconsciously, the new regime in Myanmar ignored that the Rohingyas also organized a revolt against the colonizers after they retracted their promise to provide partial independence to the ethnic group, despite fighting against the Japanese in 1942.xxxi After Burma achieved independence, the Rohingyas were stripped of their citizenship rights in the 1948 Constitution, and the manifestation of this discrimination continued to be visible in the 1974 Constitution and in the 1982 Citizenship Law, while the latter declared that the Rohingyas explicitly are “foreigners.”xxxii On one hand, the Rohingyas were systematically deprived of their basic rights to education, food, shelter, and health; on the other hand, several operations (i.e., Operation Sapay in 1974 and Operation Nagamin in 1977) were carried out as a means of ethnoracial profiling of these groups and to forcefully drive them out of the country.xxxiii

For Bangladesh, Operation Nagamin had specific implications, since it was the first time the country faced a mass exodus of 200,000 Rohingya refugees from Myanmar. Reports from the UNHCR suboffice in Cox’s Bazar showed that almost 250 villages had been destroyed during the operations in Myebon and Maungdaw townships alone.xxxiv During that time, the Government of Bangladesh (GoB) and the International Committee of the Red Cross provided the Rohingyas with immediate protection and relief. As a newly emerged state, Bangladesh was unable to deal with the overwhelming number of refugees. Eventually, it had to call for international support, and the U.N. established 13 camps in Cox’s Bazar.xxxv Treatment and protection of the refugees at this stage ended with the repatriation of 187,250 Rohingyas to Myanmar after an agreement was reached between the two countries.xxxvi

Bangladesh faced the second mass exodus of 250,000 Rohingya people in 1992. During this time, UNHCR was directly involved from the very first stage, and 13 camps were set up in Cox’s Bazar.xxxvii The GoB and UNHCR started to work in tandem to resolve the crisis; and by October 1992, they had started working together to facilitate voluntary repatriation of the Rohingyas. However, by 1994, UNHCR’s emphasis on “voluntariness” and the GoB’s emphasis on fast repatriation led to contradictions between them.xxxviii Eventually, UNHCR gained access to the Arakan townships and approximately 230,000 Rohingya people were repatriated to Myanmar.xxxix

After the repatriation, the uneasy relationship between the Rohingyas and the Myanmar state continued to worsen over the year. Not to mention, neither the discrimination against the Rohingyas stop; nor did the strings of incidents that included persecution, rape of women and girls, torture, and extortion. In 2013, the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA), initially named Harakah al-Yaqin (Faith Movement), emerged as the frontline revolutionary and insurgent organization advocating for the plight of the Rohingyas. The presence of ARSA was first felt through the 2016 attacks on Myanmar’s Border Guard Police bases in Northern Rakhine State.xl The ultranationalist Buddhist organization called Ma Ba Tha was also established in 2014. Together with Ma Ba Tha’s anti-Islamic and prejudicial political campaign, the military junta organized a brutal crackdown on the Rohingyas in 2017 that resulted in the largest refugee crisis in Asia in the 21st century. Approximately 700,000 Rohingya people fled Myanmar and took shelter in Bangladesh, adding to the number of refugees living in the camps.xli

Primarily emphasizing the “repatriation” agenda, the GoB started diplomatic talks with Myanmar while providing assistance to the camps with the help of international agencies and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). Even though Bangladesh and Myanmar reached an agreement in 2018 regarding repatriation, stagnating developments regarding verification slowed the process down. At the same time, the COVID-19 pandemic and the 2021 coup d’état in Myanmar exacerbated the downward trend. The initial idea of repatriation talks started off with China’s proposed “three-stage plan” – which incorporated an immediate cease-fire, intermediary bilateral talks, and a final stage that necessitated international support for a long-term solution – in the background.xlii The two countries also set up an Ad-Hoc Task Force for Verification of the Displaced Persons from Rakhine and, in 2022, the first meeting of the committee took place (Rohingya Repatriation, 2022). Even though the first two stages were successful to some extent, it is important to examine how the third stage is developing. Going back to Whitaker’s point about the convergence of “protection” and “assistance” for refugees,xliii one needs to take into account whether global support from international and regional communities is addressing both these areas or if they are adequate to address the needs of refugees.

- Nature and Critique of Responses to the Rohingya Refugee Crisis

The responses to the Rohingya refugee crisis have primarily depended on host countries’ policies and assistance from international agencies and NGOs. Although the Rohingya community has been facing physical, psychological, and gender-based violence from its own country for more than half a century, any instrument of responsibility to protect has never been adopted by the international community based on the U.N. Charter.

The primary struggle with the nature of responses, however, stems from two pertinent issues: the organizational structure of the refugee protection program, and the nature of legally binding frameworks or the lack thereof. Even 73 years since its establishment, UNHCR still operates as the only coordinating body when it comes to refugeehood and forced migration, and it is still dependent on voluntary contributions from donor states. As Whitaker has noted,

UNHCR depends entirely on voluntary contributions for its field operations. The agency receives just 2 percent of its funds from the U.N. general budget for headquarters staff. The remaining 98 percent of an annual budget must be raised through appeals to U.N. member states and other donors. The vast majority of the agency’s funding comes from industrialized countries, with the United States, the European Union, and Japan together accounting for 94 percent of government contributions. … As a result of this funding structure, UNHCR is highly vulnerable to fluctuations in the level of donor contributions.xliv

Conversely, the 1951 Refugee Convention is the only convention serving as a core legal document for the status and protection of refugees. Not only has the convention become outdated,xlv it is also unable to address newly emerging challenges and needs. Moreover, neither Myanmar nor Bangladesh is a signatory of the convention. Nevertheless, it must be mentioned that, in a 2017 verdict regarding the imprisonment of a Rohingya person, the High Court of Bangladesh used the clauses of the Refugee Convention and mentioned it as a “customary international law,” despite that country not being a signatory (discussed further below in 4.1). To quote from the verdict,

“[The Refugee] Convention by now has become a part of customary international law which is binding upon all the countries of the world, irrespective of whether a particular country has formally signed, acceded to or ratified the convention or not.”xlvi

Bangladesh has also shown compliance with the convention by providing shelter and assistance to refugees for decades. However, in this case, ensuring Bangladesh’s compliance alone cannot bring any positive outcome, unless Myanmar also does so. While it is highly unlikely, intervention by the international community and protection programs can put pressure on Myanmar.

To understand the nature and trends of responses, this subsection divides the discussion into two phases.

- Pre-2017 Influx Trends

After the exodus in the 1990s, institutional arrangements between Bangladesh and UNHCR were established. In 1993, a memorandum of understanding was signed, which mentioned “technical assistance and financial support.” However, UNHCR’s Policy Development and Evaluation Service pointed out in its evaluation report that no tangible attempts were seen until 2006. At the same time, geopolitical stakes and concerns dominated regional and extra regional countries’ responses to the Rohingya crisis. For example, during the 1990s, China was a major trading partner of Myanmar, and due to its economic interests, it did not want to become involved in the crisis, despite having a major influence on Myanmar’s State Law and Order Restoration Council.xlvii

During this period, however, multiple IGOs and NGOs extended their humanitarian aid and development programs to address the plight of the Rohingyas in Bangladesh. The European Commission launched its Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection department (ECHO) program to Bangladesh in 1994 to provide relief to the Rohingya refugees. Between 2007 and 2017, until the new phase of the refugee crisis started, ECHO provided about 30 million euros for healthcare, shelter, water, sanitation, and education for the Rohingyas.xlviii Subsequently, it started closely working with the International Organization for Migration.

The UNHCR Policy Development and Evaluation Service’s report provides a list of collaborative measures taken during that phase, including a $33 million pledge from the European Union, Australia, and the Dhaka Steering Group, which wanted to collaborate with the U.N. Join Initiative for programs targeting the U.N. Millennium Development Goals in Cox’s Bazar. Nevertheless, the government turned down the project under the accusation of unauthorized rehabilitation in the name of poverty reduction in the host communities. In 2012, the GoB denied shelter to the refugees for the first time, mentioning the erstwhile situation and the presence of 400,00 Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh, which was already overwhelming the country.xlix

During this period, the protection of Rohingyas’ social and civil rights was taken up by organizations like Bangladesh Legal Aid and Services Trust (BLAST), Refugee and Migratory Movements Research Unit (RMMRU), and Ain o Salish Kendra (ASK). One example was RMMRU’s involvement against the conviction of a Rohingya man in 2011 for unlawful entry under Section 3 of the Foreigners Act 1946 after his arrest in 2007. The verdict established that no person, whether a citizen or noncitizen, “should be kept in detention after the completion of a sentence or term of imprisonment for any criminal offence.”l BLAST also built awareness regarding the laws “beyond refugees” that would subsequently be applicable to noncitizens. These included constitutional law, fair trial rights, protections for victims and witnesses of crimes, and the like. Among other NGOs, Brac contributed to reconstruction, building shelters, and providing education as part of its work in the Cox’s Bazar region.li

The initiatives undertaken by regional organizations in Asia were barely visible. It was also the NGOs that wanted to push the Rohingya protection agenda through the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), given that ASEAN member states like Malaysia and Thailand were also recipients of Rohingya refugees. The ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights included the plight of the Rohingyas as a discussion point. The issue was supported by only two representatives, while the rest refused to consider it as a regional or global concern.lii

- Post-2017 Influx Trends

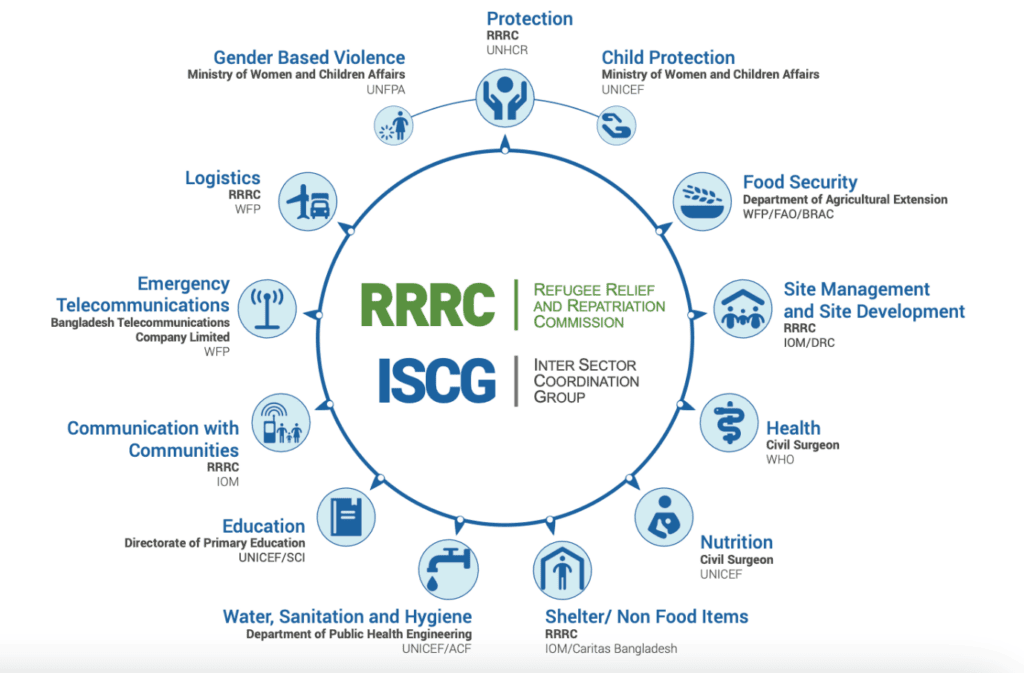

More coordinated efforts for the Rohingya refugees were seen after the 2017 influx. Establishment of the Refugee Relief and Repatriation Commissioner (RRRC) and the National Task Force (NTF), in coordination with the Ministry of Disaster Management & Relief, contributed positively to the immediate response. A strategic executive group was also formed, with the International Organization for Migration’s chief, the U.N. Resident Coordinator, and a UNHCR representative as co-chairs. The Inter-Sector Coordination Group (ISCG) was formed for information management, external relations management, and thematic management. More importantly, the ISCG incorporated myriad dimensions under the protection framework and designated different organizations as focal points (figure 1). As the framework suggests, RRRC itself is directly involved in protection, site management, logistics, communications, and shelter. Relevant ministries, U.N. agencies – like the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) (gender-based violence), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) (nutrition, education, child protection), the World Food Program (food security, logistics, telecommunications), and the World Health Organization (WHO) (Health) –and NGOs like Brac (food security) are directly included in the coordination framework.

Figure 1. Humanitarian Stakeholders in the Rohingya Crisis

Source: ISCG.

Other organizations have also been working in different capacities. Between 2017 and 2023, Action Aid supported 657,000 Rohingya refugees in Cox’s Bazar, particularly by creating and operating in women-friendly spaces and providing medical referrals, hygiene kits, and psychosocial support.liii Brac started to work as part of water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) in September 2017 and ensured WASH facilities (e.g., functioning tube-wells, latrines, gas, and wastebins) for 365,697 people.liv

Another salient trend at this stage pertained to research and awareness-building. Hence, research organizations like Research Initiatives, Bangladesh (RIB), and the Centre for Genocide Studies (CGS) at the University of Dhaka have left their vivid footprints. RIB has developed a “childhood learning model” called the Kajoli Model and applied it to educating Rohingya children in the camps. It has also established mass research teams, called Participatory Action Groups (Gonogobeshona Dol), to utilize participatory action research as an instrument against gender-based violence in the camps.lv CGS’s peace observatory, funded by the Partnerships for a Tolerant and Inclusive Bangladesh project of the United Nations Development Program, organized multiple gatherings of the International Conference on Genocide and Mass Violence, which included the “Dhaka Declaration” to resolve the crisis with the help of international partners, global humanitarian networks, and the Rohingya diaspora.lvi

Among global institutions, the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) and the EU came forward with notable contributions. OIC backed the Gambia v. Myanmar case filed before the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in 2019. The organizations also called for repeated actions against the genocidal acts of Myanmar. The OIC chief has also recently visited the Rohingya camps in Cox’s Bazar in May 2023 and shared concerns about the funding shortage. Conversely, the EU has been a significant partner in the Joint Response Plan (JRP). It has committed financing through three source organizations: the European Commission (EC), the EC Directorate-General for International Partnerships (formerly EuropeAid DEVCO), and the European Commission’s Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection Department. Under the JRP for 2023, the EU’s funding covers 3.5%. Among other donor organizations, UNHCR covers 1.9% ($30,630,700), the International Labor Organization covers 0.1% ($530,295), and Save the Children covers 0.1% ($1,274,600). Among individual countries, the U.S. covers 10.4% ($90,700,000), Japan covers 1.8% ($15,918,550), Australia covers 3.3% ($28,706,327), and Canada covers 0.9% ($7,897,197). Interestingly, despite the Rohingya issue being branded globally as an ethnoreligious issue targeting the Muslim community, Qatar ($205,353) and the United Arab Emirates ($1,000,000) are the only two Arab countries that are committed to contribute via the JRP for 2023. Although Turkey provided financial support to the camps directly in fiscal years (FYs) 2021 and 2022, FY 2023 has seen a sharp decline. Yet one must note the fact that it has donated $200,000 for the genocide trial in the ICJ.lvii

Perhaps, an issue of more concern than the percentage of allocation is the increasing trend of unmet funding. Figure 2 shows the percentage of total funding and unmet requirements between 2020 and 2023. Almost all the years had to face unmet requirements, and the 2023 situation is not satisfactory at all. Moreover, these funds are not enough to address the plight of the 1.1 million refugees comprehensively. According to a 2022 statement by UNHCR,

The support from the international community has been and is crucial in delivering lifesaving protection and assistance services for Rohingya refugees but funding is well short of needs.

Figure 2. Trends in the Rohingya Response Plan / Appeal Requirements (in billions of dollars)

Source: UNOCHA, 2023.

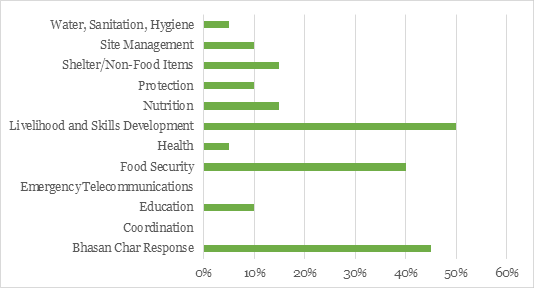

The U.N. resident coordinator in Bangladesh, Gwyn Lewis, in her interview with Prothom Alo (Bengali Daily) on March 11, 2023, also echoed such concerns.lviii She significantly highlighted the funding cuts from the WFP, which fails to address the marginal food requirement of 2,100 kilocalories per day for refugees. She also mentioned the demand of additional funding for the newly established Bhasan Char camps, which can be seen in the cluster-based distribution in figure 3. The funding clusters also show the lesser allocations for health and education, which requires further attention. The number of donor organizations involved has also been reduced, from 477 in 2021 to 280 in 2022 to 131 in 2023.lix

Figure 3. Progress in Funding the Bhasan Char Camps, by Cluster

Source: UNOCHA, 2023.

When it comes to respective country-based funding, there is a gap that is a cause of concern in terms of what is committed and what is provided. Although the U.S. is the largest donor of refugee funds, except in 2022, the unmet requirements of funds remained more than 50% (Table 1).

Table 1. U.S. Funding for the Rohingya Refugees Over the Years

| Year | U.S. Funding (millions of dollars) | Percentage of Total Fund Received |

| 2017 | 89.31 | 27.11 |

| 2018 | 241.46 | 34.11 |

| 2019 | 247.38 | 35.8 |

| 2020 | 331.22 | 49.8 |

| 2021 | 298.59 | 43.9 |

| 2022 | 336.69 | 60.6 |

Source: Compiled by Abu Salah Md Yousuf from U.N. Factsheets, OCHA documents, and HRW reports, 2023.

Unfortunately, regional initiatives and responses from individual states have not advanced at a similar pace. The ASEAN has continued its distant position from the previous phase and kept its agenda of “noninterference” at the fore. However, it included the repatriation issue of the Rohingyas in its 2019 ASEAN foreign ministers’ forum, and it opted for further developments through the ASEAN Coordinating Centre for Humanitarian Assistance on Disaster Management.lx The geoeconomic issues here also cannot be ignored. ASEAN member states – like Singapore, Thailand, Malaysia, and Brunei – are among the top 10 investors in Myanmar, while Singapore is holding the peak position, with $275 million.lxi Similar to the ASEAN, the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC) has also failed to address the concerns of the refugees and their protection. Not to mention, BIMSTEC is the only subregional group for South and Southeast Asia that includes both Bangladesh and Myanmar. In this case, BIMSTEC overemphasizes on its “technical” and “economic” agenda, ignoring how the security dynamics of the region are also closely related to both. Banerjee here has pointed out that the silence of BIMSTEC shows the limits of the subregion in dealing with forced displacement of people from one member state to another.lxii Bangladesh’s high commissioner to India, Syed Muazzem Ali, in his interview with Press Trust of India (PTI), rightly mentioned how it may also affect the connectivity projects of BIMSTEC:

On the BIMSTEC, unless and until we resolve the refugee problem, we will not be able to make significant progress on the connectivity question. It is a common desire to build connectivity between India, Bangladesh with southeast Asian region and that would first require passing through Myanmar.lxiii

4.3 Geopolitics, Geoeconomics and Humanitarian Aid

When it comes to individual countries, the combination of geopolitics and geoeconomics has had a major influence on the pattern of responses. These countries have direct diplomatic and economic ties with Myanmar. At the same time, a number of international companies have ongoing projects in the Rakhine region. Maintaining strong diplomatic ties with (and not imposing any sanction on) Myanmar is important for them to continue these projects. The business companies’ roles in international politics are also larger than the business itself, i.e., as lobbyists. It explains why most actions of the international community are either verbal and rhetorical and why they hardly reach the point of sanctions or any direct maneuver.

Apart from the ASEAN states, among Myanmar’s top investors are China ($133 billion), Thailand ($24 billion), Hong Kong ($5.1 billion), South Korea ($5 billion), the United Kingdom ($2 billion), Malaysia ($2.1 billion), and India ($1.1 billion).lxiv These investments help Myanmar in two ways: as an element of resource diplomacy for oil and natural gas, and by enhancing trade and connectivity projects.

Myanmar is a part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. China has invested in the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor connecting Ruili (Yunnan Province) and Khyaukphyu (Rakhine state). The corridor also includes a Special Economic Zone (SEZ) in Khyaukphyu (KPSEZ). The country is also financially involved in Myanmar’s connectivity projects, like the $9 billion Muse-Mandalay Railway construction.lxv There are additional projects in the area, including the $180 million Kyaukphyu Power Plant, the $1.3 billion Kyaukphyu deep sea port, and a $2.5 billion oil and natural gas pipeline.

Conversely, India also has similar stakes in Myanmar. In 2019, India signed an agreement with Myanmar’s state-owned oil and gas enterprise worth $722 million.lxvi In Rakhine state, India has the $484 million Kaladan road project, the Thathay Chaung Hydropower Project, the $120 million Sittwe SEZ, and the $3 billion Sittwe–Gaya gas pipeline project. Not to forget that this SEZ is a rival project to China’s KPSEZ and that Sino-Indian geopolitics has a role to play here.

As part of Japan’s official development assistance, in 2016 Myanmar sanctioned a $240 million loan from the Japan International Cooperation Agency for the Bago River Bridge Construction Project. In 2019, Yokogawa Bridge Corporation of Japan signed a contract to build the bridge.lxvii Again, Russia is known to be one of the top arms suppliers in the Myanmar military.

A number of international companies are also carrying out projects in Rakhine. Table 2 shows a list of companies that have ongoing projects in Rakhine state. It is easily visible from the table that most of these companies are involved in projects related to oil and gas. This shows how important it is for Myanmar as well as the international companies to have dominance over Rakhine for natural resources. Among these companies, only Total (France) and Chevron (U.K.) announced departures in 2022, mentioning “gross human rights violations.”lxviii

Table 2. International Companies That Have Ongoing Projects in Rakhine State

| Country | Company | Project Type |

| Australia | Woodside Energy (Myanmar) Company Limited | Oil & Gas |

| China | Kyauk Phyu Electric Power Company Limited | Power |

| PetroChina | Oil & Gas | |

| China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) | Oil & Gas | |

| Finland | Ha Nam CMC Co., Ltd | Tourism |

| France | Total | Oil & Gas |

| Italy | Eni | Oil & Gas |

| Norway | Statoil | Oil & Gas |

| Sweden | DnA Hotels and Resorts Co. | Tourism |

| Ziba Hotels and Resorts Co., Ltd | Tourism | |

| Thailand (Joint) | Myanmar CP Livestock Company Limited | Agriculture |

| U.K. | BG Group | Oil & Gas |

| Ophir | Oil & Gas | |

| Shell | Oil & Gas | |

| U.S. | Chevron | Oil & Gas |

| Conoco Phillips | Oil & Gas |

Source: Compiled by the authors from various sources.

The positions of business cooperations are critical in the current age. For example, after the beginning of the Ukraine war, top policy schools and media tracked the positions of different companies and their projects in Russia. The Yale School of Management listed 1,000 companies that curtailed their operations in Russia and also named those (including Chevron) that did not.lxix Global media, from Reuters to The New York Times, covered the issue. The conventional wisdom regarding the issue here was that “there should not be business engagement with a country that is waging war or causing humanitarian concerns.” If it applies to Russia, it should also apply to Myanmar, which has conducted genocide within its own territory. The Woodrow Wilson Center, moreover, provided a strong argument that these companies and their revenues helped Russia “underwrite” the warlxx and gave indirect logistical support. As one can expect, scholars here advocated for curtailing the businesses to stop the war. There has been no such focus from the global media or academia when it comes to the investments in Myanmar or Rakhine state.

Again, business actors can influence foreign policies of a country. To quote Kirshner,

If war unnerves finance, and if international financial markets reflect the cumulative sentiments of uncoordinated market actors, then finance (figuratively) will withdraw from, or at least be especially wary of, those states that seem to be approaching the precipice of armed conflict. … By raising the opportunity costs that states face when considering a resort to arms, financial globalization can serve, ceteris paribus, to inhibit war.lxxi

Practically, there is not enough evidence of business lobbies having successfully stopped a conflict; rather, scholars have shown cases where they have lobbied to continue a conflict, i.e., the Iraq war/ and the war on terrorism.lxxii Nevertheless, given their degree of influence, it is theoretically possible for business groups and lobbies to shift the discourse to a certain pathway, or at least resort to temporary withholding.

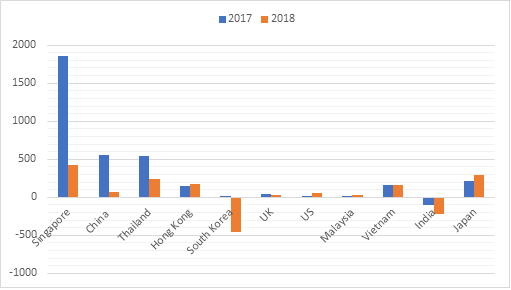

However, it cannot be stated that the Rohingya crisis has had no impact at all on investment flows. Many of these countries have also foreseen the risk, and foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows declined to some extent after the 2017 massacre. The trends of actual FDI inflows to Myanmar in FY 2017 and 2018 separately show the distinction (figure 4). U Aung Naing Oo, the director general of Myanmar’s Directorate of Investment and Company Administration (DICA), openly acknowledged in 2018 that he had “underestimated” the effect of the Rohingya issue on the nation’s economy.lxxiii

Figure 4. FDI Inflows (Actual) to Myanmar; Investment Transactions, 2017 and 2018 (in millions of dollars)

Source: Authors’ compilation from actual FDI inflows, DICA.

Although the FDI in Myanmar increased in subsequent years, it again started to decline after the 2021 coup and human rights violations. These pieces of information have not been presented here since that would dilute the issues evolving vis-à-vis the Rohingya crisis exclusively, to which this paper limits its scope. However, it is to notice that the global purview of “Myanmar’s violation of human rights” has starkly shifted to its authoritarianism and the civil rights movement from the Rohingya crisis. While it is also an important factor to take into account, the international community must not ignore the plight of the Rohingyas or overlook its propensity.

- Concluding Remarks

This paper has made an attempt to demonstrate the politics of humanitarian aid in refugee and refugee-like situations. Tracing from the beginning of the Rohingya crisis and the humanitarian responses – both national and international – the paper has attempted to posit the decline of humanitarian aid. Increasingly, hardcore traditional geopolitical issues have taken priority in state calculations while responding to humanitarian issues. The above-noted points, indeed, show that this is a worrisome issue, as the number of refugees and displaced persons is on the increase. In light of the narration above, the paper makes the following multipronged recommendations involving multiple actors; the epistemic society, political leaders, policymakers, civil society groups, citizens’ organizations, NGOs, and INGOs have major roles to play in this regard. In each of the recommendations made here, the actors noted are critical factors in the intervention:

- At the epistemic as well policy level, the humanitarian aspect of refugees and people in refugee-like situations needs to be highlighted.

- It is critical that the statist narrative of border and geopolitics should be delinked from humanitarianism; critical research, civil society groups, and human rights bodies have major roles to play here.

- The securitization of the refugee narrative needs to be deconstructed by highlighting the differentiated nature of the refugee population, the majority of whom are women and children.

- Donors and aid agencies need to understand that “refugees” are not a monolithic group; rather, refugees, like any other human population, are a differentiated group; and thereby they must address the needs and concerns of the differentiated nature of the refugee population, for, e.g., women, children, women-headed households, orphan children, elderly people, and people with special needs. The aid must be need-specific, for this necessary ground work as well research might be required by the donors as well the host country.

- The refugee community must be given life-survival skills and training, and it needs to be remembered that no community wants a life of aid dependence; the host country, the donors, and the NGOs active in the refugee camps need to prioritize this principle.

- It is necessary to incorporate the voices of the refugee population at the policy level by the donors, aid agencies, and the host country.

- At the global level, the Rohingya diaspora can play an active role in bringing together the voices of the Rohingya people.

- Media, electronic, print, social, plays an important role in this digitalized world; these tools may be used by academia and by state and human rights activists, as well the refugee community itself, to highlight their plight.

We conclude with the hope that the narration above and recommendations will contribute in some limited form to a better understanding of the politics associated with humanitarian assistance and aid and will be a small step toward delinking the “statist” from the “humanitarian.”

References

Abrar, C. R. (1995). Repatriation of Rohingya refugees. UNHCR’s Regional Consultation on Refugee and Migratory Movements, Colombo.

Ahmad, M. I. (2014). “Road to Iraq: The Making of a Neoconservative War.” Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Action Aid. (2023). Rohingya refugee crisis. “What is ActionAid doing in Bangladesh to help Rohingya refugees?” https://www.actionaid.org.uk/our-work/emergencies-disasters-humanitarian-response/rohingya-refugee-crisis-explained

Al Imran, H. F., & Mian, N. (2014). The Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh: A vulnerable group in law and policy. Journal of Studies in Social Sciences, 8(2).

Al Jazeera. (2022). Oil giants Total, Chevron to leave Myanmar, citing human rights. https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2022/1/21/oil-giants-total-chevron-exit-myanmar-due-to-human-rights-abuses

Ansar, A., & Md Khaled, A. F. (2021). From solidarity to resistance: host communities’ evolving response to the Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh. Journal of International Humanitarian Action, 6 (1): 1-14.

Atlani, L., & Rousseau, C. C. (2000). The politics of culture in humanitarian aid to women refugees who have experienced sexual violence. Transcultural Psychiatry, 37 (3): 435-449.

Azad, A., & Jasmin, F. (2013). Durable solutions to the protracted refugee situation: The case of Rohingyas in Bangladesh. Journal of Indian Research, 1 (4): 25-35.

Barnett, L. (2002). Global governance and the evolution of the international refugee regime. International Journal of Refugee Law, 14 (2 & 3), 238-262.

Banerjee, S. (2021). Can Rohingya issue block the development of BIMSTEC? ORF Raisina Debates. https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/can-rohingya-issue-block-development-bimstec/

Bangladesh Legal Aid and Services Trust (BLAST). (2023) Beyond Refuge: Advancing Legal Protections for Rohingya Communities in Bangladesh. Dhaka, BLAST and Refugee Solidarity Network.

Brac. (2023). “Sustainable WASH for Rohingya Crisis.” Profile: Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. Dhaka: Brac.

Chandan, S. K. (2020, August 27). 2nd Dhaka Declaration: Ensure safe, dignified, informed and voluntary repatriation of the Rohingya people. Daily Star. https://www.thedailystar.net/rohingya-crisis/news/2nd-dhaka-declaration-ensure-safe-dignified-informed-and-voluntary-repatriation-the-rohingya-people-1951581

Czaika, M., & Mayer, A. (2011). Refugee movements and aid responsiveness of bilateral donors. Journal of Development Studies, 47 (3): 455-474.

Daily Star. (2022). Turkey donates $2 lakh for trial of Rohingya genocide case filed by Gambia. (March 23). https://www.thedailystar.net/rohingya-influx/news/turkey-donates-2-lakh-trial-rohingya-genocide-case-filed-gambia-2988801

Difficult to move ahead on connectivity under BIMSTEC unless Rohingya issue resolved: Bangladesh. (2018, May 31). The Indian Express. https://indianexpress.com/article/india/difficult-to-move-ahead-on-connectivity-under-bimstec-unless-rohingya-issue-resolved-bangladesh-5199214/

Dreher, A., Fuchs, A., & Langlotz, S. (2019). The effects of foreign aid on refugee flows. European Economic Review, 112: 127-147.

Easton-Calabria, E. E. (2015). From bottom-up to top-down: The “pre-history”of refugee livelihoods assistance from 1919 to 1979. Journal of Refugee Studies, 28 (3): 412-436.

ECHO. (2016). “Factsheet: The Rohingya crisis.” Brussels: EC, 2016.

Edwards, A. (2012). Temporary protection, derogation and the 1951 Refugee Convention. Melbourne Journal of International Law, 13 (2): 595-635.

Feller, E. (2001). The evolution of the international refugee protection regime. Wash. UJL & Pol’y, 5: 129.

Fitzpatrick, J. (1996). Revitalizing the 1951 refugee convention. Harv. Hum. Rts. J., 9: 229.

Gatrell, P. (2017). Refugees – What’s wrong with history? Journal of Refugee Studies, 30 (2): 170-189.

Grundy-Warr, C., & Wong, E. (1997). Sanctuary under a plastic sheet – the unresolved problem of Rohingya refugees. IBRU Boundary and Security Bulletin, 5 (3): 79-91.

Haque, M. M. (2017). Rohingya ethnic Muslim minority and the 1982 citizenship law in Burma. Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, 37 (4): 454-469.

Harris, C. D., & Wülker, G. (1953). The refugee problem of Germany. Economic Geography, 29 (1): 10-25.

Hathaway, J. C. (1984). The Evolution of Refugee Status in International Law: 1920 – 1950. International & Comparative Law Quarterly, 33 (2): 348-380.

Human Rights Watch. (2000). Historical Background – Rohingya Crisis. https://www.hrw.org/reports/2000/burma/burm005-01.htm

Ibrahim, A. (2018). “The Rohingyas: Inside Myanmar’s Genocide.” London: C. Hurst & Co.

International Crisis Group (ICG). (2016, Dec. 15). Myanmar: A New Muslim Insurgency in Rakhine State. https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-east-asia/myanmar/283-myanmar-new-muslim-insurgency-rakhine-state

Jati, I. (2017). Comparative Study of the Roles of ASEAN and the Organization of Islamic Cooperation in Responding to the Rohingya Crisis.

Karo, B., Haskew, C., Khan, A. S., Polonsky, J. A., Mazhar, M. K. A., & Buddha, N. (2018). World health organization early warning, alert and response system in the Rohingya crisis, Bangladesh, 2017–2018. Emerging infectious diseases, 24 (11): 2074.

Keshgegian, F. A. (2009). ‘Starving Armenians”: The Politics and Ideology of Humanitarian Aid in the First Decades of the Twentieth Century. In Wilson and Brown, eds., Humanitarianism and Suffering, 148-52.

Khanom, S. & Shoieb, M. J. (2022). Sustainable Repatriation Options. In “Repatriation of Forcibly Displaced Myanmar Nationals: Political Security and Humanitarian Assistance.” BIISS Papers, 31.

Kipgen, N. (2019). The Rohingya crisis: The centrality of identity and citizenship. Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, 39 (1): 61-74.

Kiragu, E., Rosi, A. L., & Morris, T. (2011). States of denial: A review of UNHCR’s response to the protracted situation of stateless Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh. Policy Development and Evaluation Service, UNHCR.

Kirshner, J. (2007). Appeasing bankers: Financial caution on the road to war (Vol. 104). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Leider, J. P. (2018). History and victimhood: Engaging with rohingya issues. Insight Turkey, 20 (1): 99-118.

Lewis, D. (2019). Humanitarianism, civil society and the Rohingya refugee crisis in Bangladesh. Third World Quarterly, 40 (10): 1884-1902.

Loescher, G. (2001). “The UNHCR and world politics: A perilous path.” Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Loescher, G. (2017). UNHCR’s origins and early history: agency, influence, and power in global refugee policy. Refuge, 33: 77.

Miah, M.R. & Khan, M.N.S. (2022). Introduction. In “Repatriation of Forcibly Displaced Myanmar Nationals: Political Security and Humanitarian Assistance.” BIISS Papers, 31.

Millbank, A. (2016). “Moral confusion and the 1951 Refugee Convention in Europe and Australia.” Victoria: Australian Population Research Institute.

Mohajan, H. (2018). History of Rakhine State and the origin of the Rohingya Muslims. Indonesian Journal of Southeast Asian Studies.

Mutaqin, Z. Z. (2018). The Rohingya refugee crisis and human rights: What should ASEAN do? Asia-Pacific Journal on Human Rights and the Law, 19 (1): 1-26.

Myanmar: Japan’s Construction Aid Benefits Junta. (2023, Jan. 23). Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/01/23/myanmar-japans-construction-aid-benefits-junta

Ngolle, E. O. N. (1985). “The African Refugee Problem and the Distribution of International Refugee Assistance in Comparative Perspective: An Empirical Analysis of the Policies of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), 1960-1980.” University of Denver.

Nikkei Asia. (2023). Myanmar military receives Japan aid for bridge construction. (January 25). https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/International-relations/Myanmar-military-receives-Japan-aid-for-bridge-construction

Paulmann, J. (2013). Conjunctures in the history of international humanitarian aid during the twentieth century. Humanity: An International Journal of Human Rights, Humanitarianism, and Development, 4 (2): 215-238.

Petcharamesree, S. (2016). ASEAN and its approach to forced migration issues. International Journal of Human Rights, 20 (2): 173-190.

Daily Prothom Alo (English Version). (2023). Interview: Gyan Lewis. By Raheed Ejaz & Ayesha Kabir. https://en.prothomalo.com/opinion/interview/8bismj9jxa

Republic of the Union of Myanmar, Ministry of Investment and Foreign Economic Relations (MIFER). Directorate of Investment and Company Administration (DICA) (2017-23). Myanmar Investment Directory. https://www.dica.gov.mm/en/myindy/private-enterprises

Republic of the Union of Myanmar, Ministry of Investment and Foreign Economic Relations (MIFER). Directorate of Investment and Company Administration (2023). Data and Statistics. Foreign Investment Data by Sector and Country. https://www.dica.gov.mm/en/topic/foreign-investment-country

Rohingya repatriation: Bangladesh, Myanmar agree to accelerate verification process. (2022, Jan. 29). Financial Express. https://thefinancialexpress.com.bd/national/rohingya-repatriation-bangladesh-myanmar-agree-to-accelerate-verification-process-1643371571

Roper, S. D., & Barria, L. A. (2010). Burden sharing in the funding of the UNHCR: refugee protection as an impure public good. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 54(4): 616-637.

Scott, P. D. (2004). “Drugs, oil, and war: the United States in Afghanistan, Colombia, and Indochina.” New York: Rowman & Littlefield.

Sengupta, S. (2018). Stateless, floating people: The Rohingya at sea. In “The Rohingya in South Asia,” pp. 20-42. New Delhi: Routledge India.

Skran, C. M. (1985). “The Refugee Problem in Interwar Europe, 1919-1939” (doctoral dissertation, University of Oxford).

Smith, M. (2019). “Arakan (Rakhine State): A Land in Conflict on Myanmar’s Western Frontier.” Amsterdam: Transnational Institute.

Strang, A., & Ager, A. (2010). Refugee integration: Emerging trends and remaining agendas. Journal of Refugee Studies, 23 (4): 589-607.

Temnycky, M. (2023, March, 22). The Western Companies Helping Underwrite Russia’s War. Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/western-companies-helping-underwrite-russias-war

Tobing, D. H. (2018). The limits and possibilities of the ASEAN way: The case of Rohingya as humanitarian issue in Southeast Asia. KnE Social Sciences, 148-174.

UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees). (2023). Refugee Statistics. https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA). (2023). Coordinated Plan Data. https://fts.unocha.org/plans/1143/flows

Vernant, J. (1953). The refugee in the post-war world.

Whitaker, B. E. (2008). Funding the international refugee regime: Implications for protection. Global Governance, 241-258.

World Vision (2023). From the Field: Rohingya refugee crisis. https://www.worldvision.org/refugees-news-stories/rohingya-refugees-bangladesh-facts

Yousuf, A. S. M. & Sabriet, N.R. (2022). The Urge for International Response to the Rohingya Crisis. In “Repatriation of Forcibly Displaced Myanmar Nationals: Political Security and Humanitarian Assistance.” BIISS Papers, 31.

Yale School of Management. (2023, Oct. 10). Chief Executive Leadership Institute. Over 1,000 Companies Have Curtailed Operations in Russia – but Some Remain. https://som.yale.edu/story/2022/over-1000-companies-have-curtailed-operations-russia-some-remain

Zarni, M. (2013). Fascist roots, rewritten histories. Asian Times Online.

This essay originally appeared in the anthology “The Accountability, Politics, and Humanitarian Toll of the Rohingya Genocide” To download the full anthology, click here.

Nahian Reza Sabriet works as a research officer at the Bangladesh Institute of International and Strategic Studies. He has bachelor’s and master’s degrees in International Relations from the University of Dhaka, Bangladesh, and is currently pursuing his second master’s at Syracuse University’s Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs. Sabriet has worked as a data analyst for the Bangladesh Peace Observatory, Centre for Genocide Studies, hosted by University of Dhaka and the United Nations Development Programme. He has been part of projects by several organizations in the field of international relations. His areas of interest are human security, homeland security, and cybersecurity, on which he has authored or co-authored several national and international publications. He tweets at @nahiansays.

Amena Mohsin is a former professor at the Department of International Relations, University of Dhaka, and currently an adjunct faculty at the Department of History and Philosophy, North South University. She graduated from the same department and later received her MA and PhD from the University of Hawaii, and Cambridge University. Mohsin has received several national and international fellowships, including the East-West Center Graduate Fellowship, CIDA International Fellowship, Commonwealth Staff Fellowship, SSRC Fellowship, and Freedom Foundation Fellowship. She writes on rights, gender and minority, state, democracy, civil-military relations, borders, and human security issues.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of the New Lines Institute.