Listen to article

Despite its geostrategic advantages, Sri Lanka is suffering an unprecedented economic crisis and social and political unrest. The roots of this situation lie in the end of a long and bloody insurgency that empowered the government’s increasingly authoritarian tendencies, driving Sri Lanka toward the brink of economic collapse and deepening ethnic and religious tensions. The United States has numerous options to support Sri Lanka and, in doing so, strengthen its presence in the region.

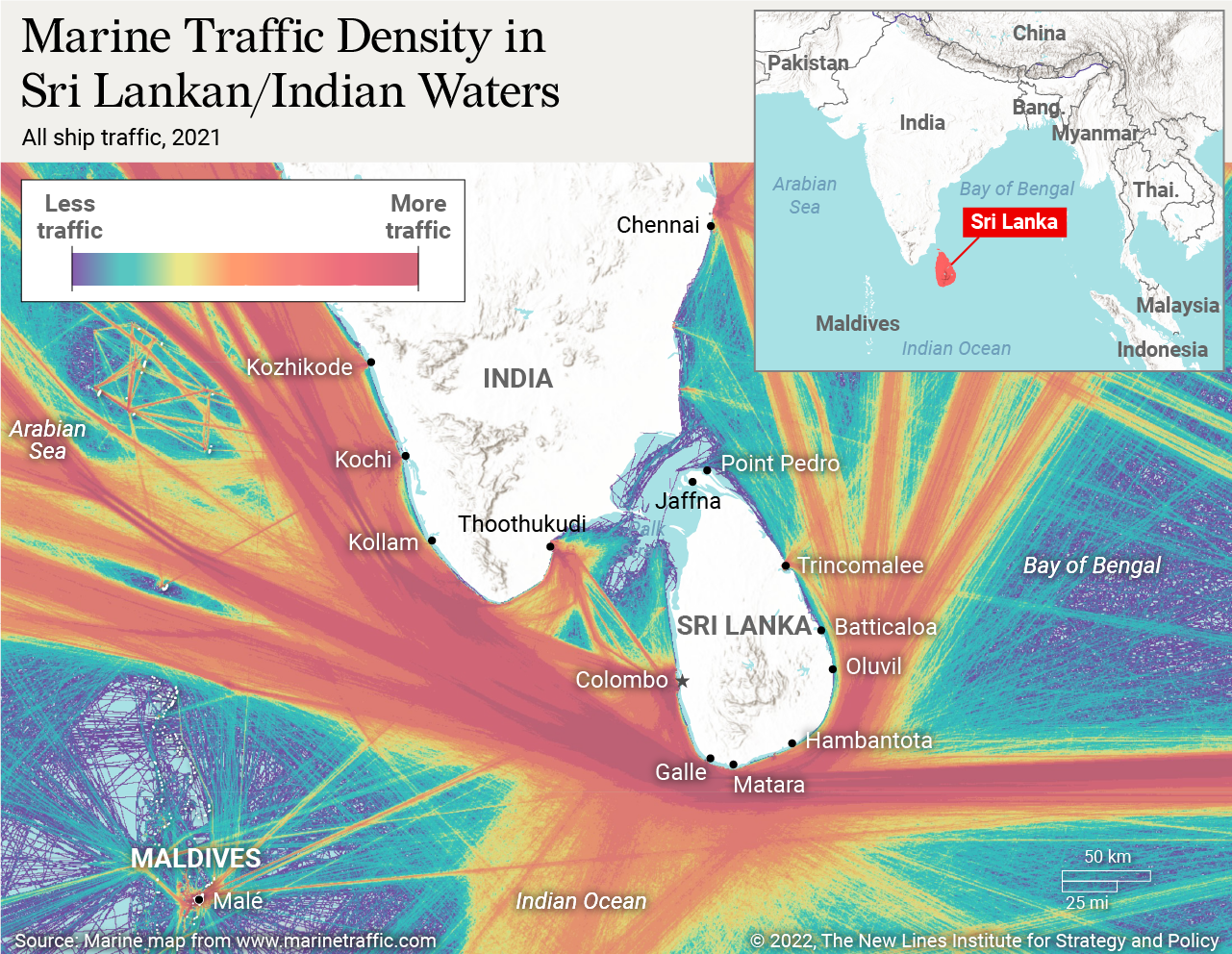

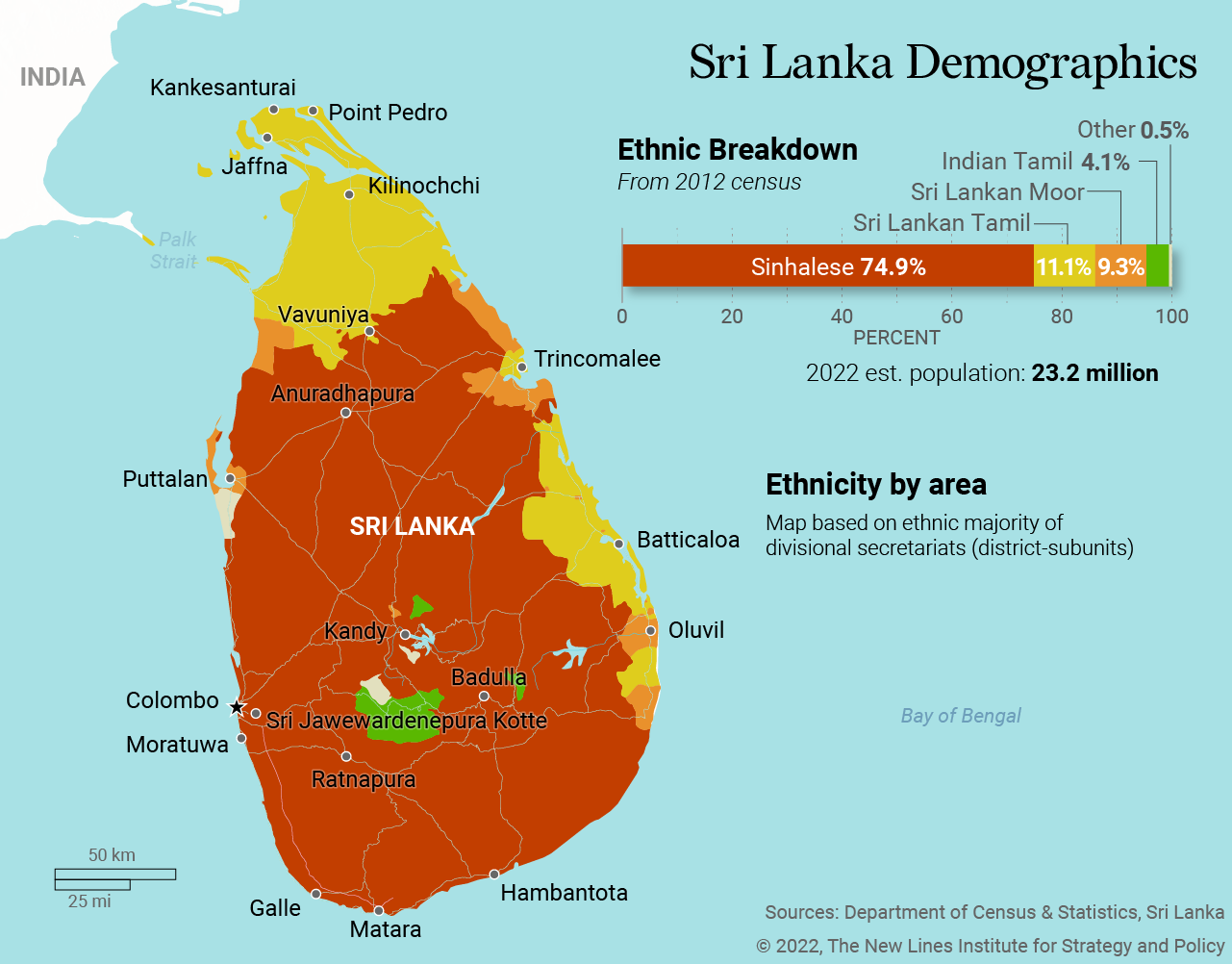

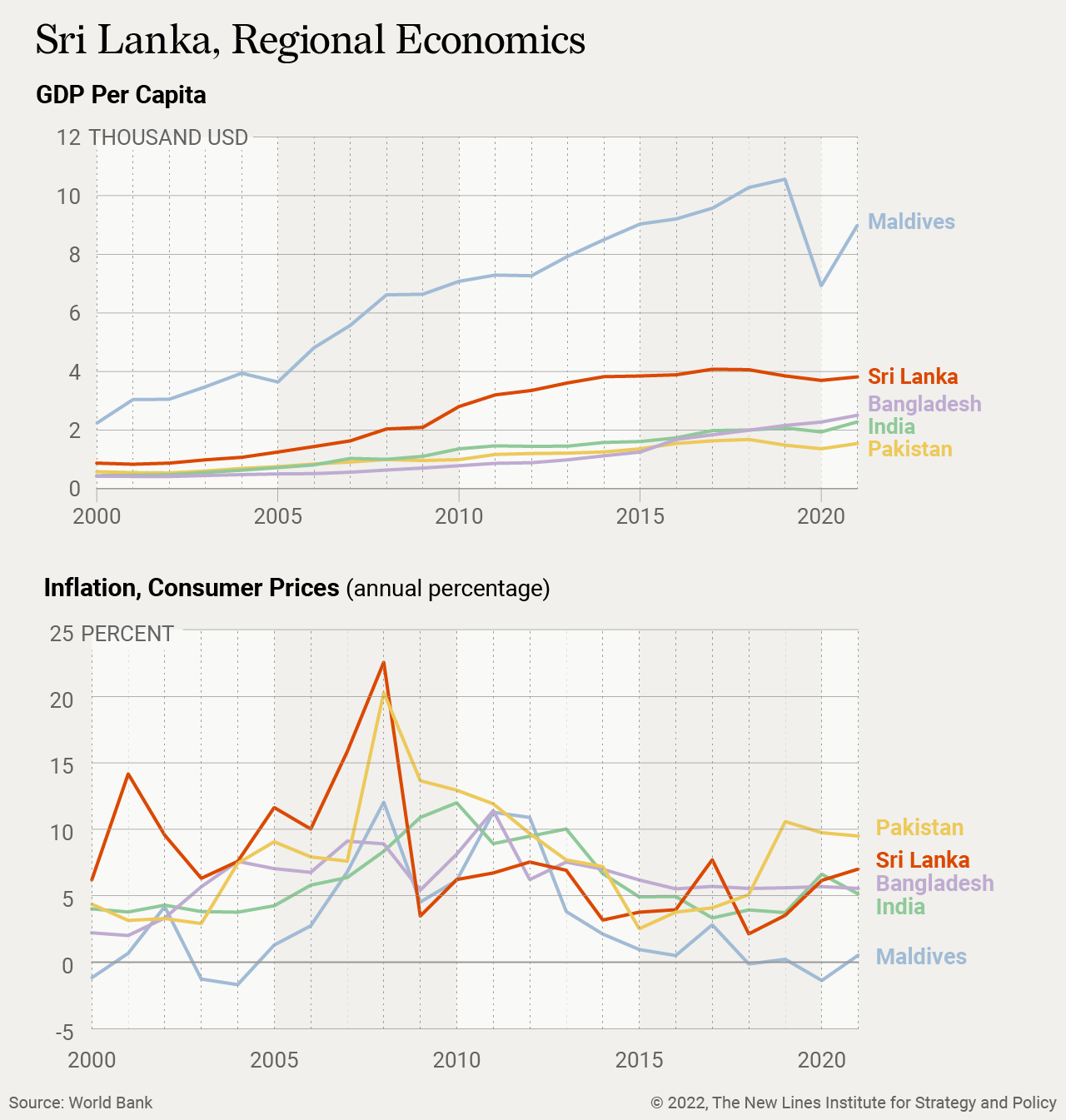

Sri Lanka, which sits astride some of the world’s busiest sea lanes in the Indian Ocean, is an ethnically diverse country of just over 23 million. Almost three in four of its citizens are Sinhalese Buddhists, but the country also has sizeable populations of Tamil Hindus and Christians, as well as a smaller Muslim minority. Despite its relatively small size, Sri Lanka has managed to achieve the highest level of human development in South Asia. The island nation’s strategic location also makes it a significant player in the Sino-American great-power competition unfolding in South Asia and across the Indo-Pacific.

Internal strife has long plagued Sri Lanka, most recently the root of a two-decade insurgency that was quashed in 2009 under the leadership of the Rajapaksa brothers. The brutality of that conflict’s end led to the emergence of an increasingly authoritarian regime controlled by the Rajapaksas, now largely responsible for bringing the country to the cusp of a severe economic crisis. Despite the recent ouster of the Rajapaskas from power, Sri Lanka has struggled to secure the international support necessary to overcome its economic troubles, and internal political tension remains high. The prevailing sentiment threatens to unleash more unrest, which could reignite ethnic strife and undermine the sense of security for ordinary Sri Lankans. Moreover, the desperation of the current Sri Lankan rulers, who are also facing a crisis of legitimacy, may nudge the country into greater reliance on China, which has been steadily investing in infrastructure projects in the country.

It is thus imperative that the U.S. focus on unfolding developments in Sri Lanka and take action to not only help stabilize the Sri Lankan economy, thus containing Chinese influence in the country, but also find ways to ease the prevalent social and political friction by supporting governance mechanisms to help curb authoritarian tendencies and enable greater accountability. The U.S. can also play an important role in harnessing international aid to achieve sustainable growth that addresses poverty while tackling the plight of religious and ethnic minorities, including the Tamils. Leaving the country to contend with its ongoing economic and political crises risks triggering another bout of violence and repression that would seriously undermine the human security of ordinary Sri Lankans.

Sri Lanka’s Civil War and the Emergence of Authoritarianism

To understand Sri Lanka’s present situation, it is necessary to understand the legacy of civil strife in the country and its ensuing implications. Ethnic and religious tensions, a remnant of its colonial past, have long bedeviled Sri Lanka, which was a British colony until it gained independence in 1948. As in other colonized nations, Sri Lanka was subject to “divide and rule” policies, in this case using the Tamil minority to rule over a Sinhalese majority. The pent-up frustrations of the Sinhalese, combined with the failure of the postcolonial Sri Lankan state to overcome them, led to a reverse majoritarian bias and to the growing alienation of the Tamil minority. Heavy-handed state repression followed a cycle of violent protests by the Tamils against the national government, leading to the instigation of a full-blown insurgency spearheaded by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) that began in 1983 and lasted for a quarter of a century.

Both sides committed atrocities, including terrorist attacks targeting civilians, extortion, and even use of child soldiers by the LTTE. Sri Lankan forces, meanwhile, responded with abductions, torture, and extrajudicial killings targeting the Tamil citizenry at large.

Pressure from its own Tamil population, and a desire to further its ambitions as a regional hegemon, drove India’s involvement in the Sri Lankan conflict. It initially provided support to the LTTE, but then it committed itself to an on-ground peacekeeping operation from 1987 to 1990. However, this operation brought Indian forces to loggerheads with the LTTE and led to a Tamil suicide bombing that killed Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi in 1991. His death severely damaged the LTTE’s reputation, leading Australia, Canada, the U.S., and India to brand it an international terrorist organization. Between 600,000 and 800,000 Tamils had left Sri Lanka during the two decades of conflict, and this diasporic community provided funds to cover over half of the LTTE’s expenditures. However, the community’s support for the militant group dried up due to its growing desperation, leading the LTTE to increasingly stifle dissent and use incrementally brutal tactics to terrorize the Sri Lankan citizenry.

Subsequently, an all-out military assault under the leadership of Sri Lankan President Mahinda Rajapaksa managed to quash the LTTE in 2009. The international community had been increasingly critical during the last days of the civil war, when the Sri Lankan army had the LTTE cornered but continued its assault without much regard for civilian casualties. However, it is worth noting that major powers like the United Kingdom and the U.S. have also been blamed for reducing their support for Tamil autonomy in order to preserve the country as a strategic ally, especially after 9/11. The People’s Tribunal on Sri Lanka in Dublin (2010 and 2013), endorsed by international human rights organizations, also blamed the U.S. and UK governments for the breakdown of the Norwegian-brokered 2002 peace talks, which could have averted much bloodshed. In total, this bloody insurgency claimed the lives of at least 100,000 people.

The Rajapaksa regime used the post-9/11 terrorism narrative to discredit the LTTE, but in the face of increasing international criticism over the escalating human toll of its military operations against the LTTE, Sri Lanka began relying on Chinese support. Besides providing military support including fighter jets, anti-aircraft guns, and air surveillance radars, China increased its bilateral aid to the country fivefold between 2007 and 2008 alone, lending a lifeline to the increasingly isolated Rajapaksa government. China also blocked a U.N. Security Council resolution to censure Sri Lanka and stepped up foreign investment there, including for construction of a deep-sea port at Hambantota, in furtherance of its goal of expanding its footprint in South Asia. Subsequently, the Chinese took over the Hambantota port on a 99-year lease from the Sri Lankan government at the end of 2017, after it could no longer afford to make interest payments on Chinese-backed loans. This move in turn prompted accusations of Sri Lanka having fallen prey to Chinese “debt-trap diplomacy.”

Nonetheless, once the LTTE was defeated, Mahinda Rajapaksa and his brother, Gotabaya, the defense minister who orchestrated the final assault on the LTTE, were hailed as war heroes. Yet, even after the LTTE defeat, the Rajapaksas did little to address allegations of serious atrocities committed by government forces or to redress the plight of ordinary Tamils whose lives had been shattered by years of conflict. The Rajapaksas also refused to cooperate with a 2014 U.N. Human Rights Council investigation into human rights violations during the civil war.

A postwar reconstruction and resettlement process was initiated with much fanfare; it was formulated to reinforce the dominant nationalist discourse and to normalize, and even valorize, the military defeat of the LTTE. Often in post-conflict countries, reconstruction processes are undertaken by civilian governments, as had occurred in East Timor, Nepal, Northern Ireland, Guatemala, and El Salvador. However, such was not the case in Sri Lanka, where government troops not only remained in Tamil areas after war but became actively involved in the post-conflict rehabilitation process itself. As a result, large scale militarization took place in the name of development across the north and northeast areas of the country where Tamils reside. The military even attempted to change the demographic composition of these Tamil region by encouraging Sinhala settlements in Tamil areas. The reconstruction efforts were also dogged by allegations of corruption and nepotism. Alongside evidence of large-scale militarization and encroachment of Sinhala settlements within Tamil areas, the targeting of political rights activists, arbitrarily detentions, and torture of perceived militants continued. Hence, the defeat of the LTTE did not end the suffering of ordinary Tamil citizens, who have been living in an atmosphere of postwar oppression.

After the defeat of the LTTE, Sinhalese majoritarianism took on religious overtones, and extremist groups such as Bodu Bala Sena (Buddhist Power Force) stepped up intimidation of religious minorities including Christians and Muslims. This disturbing mutation of ethnic intolerance into religious intolerance is doubly troubling given the country’s religious diversity.

Post-war Oppression, Mismanagement, and Chaos

During Mahinda Rajapaksa’s presidency from 2005 to 2015, his government became increasingly unpopular due to economic mismanagement and increasing authoritarianism. A new government, which took office after Rajapaksa’s electoral defeat, emphasized the need for national reconciliation. However, there was scant progress on this front given the reluctance of the military to hold its officers accountable for their actions to suppress the Tamil insurgency. Mahinda Rajapaksa returned to power again in 2018 as prime minister but was forced to step down a few months into his term after the Supreme Court deemed his appointment unconstitutional. The deadly Easter bombings by Islamic State terrorists in 2019 led to a renewed demand for ensuring security, which provided the Rajapaksas an opportunity for a political comeback. This time, Gotabaya Rajapaksa became the president and nominated his brother Mahinda to serve as prime minister. Other members of the Rajapaksa family, many of whom had been implicated in corruption cases, also returned to power and were given prestigious ministerial positions.

In order to consolidate their rule, the Rajapaksas ignored the need to urgently contend with mounting foreign debt and instead introduced populist policies, including significant tax cuts, to gain political support. Increased public expenditures, alongside declining tourism revenues due to the COVID-19 pandemic, put additional pressure on an already stressed Sri Lankan economy. In the bid to save fast depleting foreign currency reserves, the Rajapaksa government abruptly placed a ban on agrichemical imports in April 2021, with the misplaced hope that the agricultural sector would immediately transition to organic farming. This policy proved to be a disaster, and it led to a major dip in the production of tea, a major Sri Lankan export, and a shortage of food crops, in turn triggering price hikes. Sri Lanka was compelled to roll back the chemical ban before the end of 2021, but it proved too late to boost yields enough to stave off default. And in May 2022, for the first time in its history, Sri Lanka found itself unable to make interest payments on its externally owed debt.

The untenable economic situation drew widespread and escalating demands by the public for the ouster of the Rajapaksa family, which had dominated the Sri Lankan political landscape for the past two decades. After several months of political unrest, both Rajapaksa brothers stepped down, with Gotabaya fleeing the country in July. Sri Lankan lawmakers elected veteran politician Ranil Wickremasinghe as president, but he too remains a contentious figure given his strong ties to the Rajapaksas. Under Wickremasinghe’s protection, Gotabaya Rajapaksa returned to the country Sept. 3, a development that could trigger another wave of unrest despite the ongoing crackdown against protesters. The political situation in Sri Lanka is thus far from stable.

Broader Implications

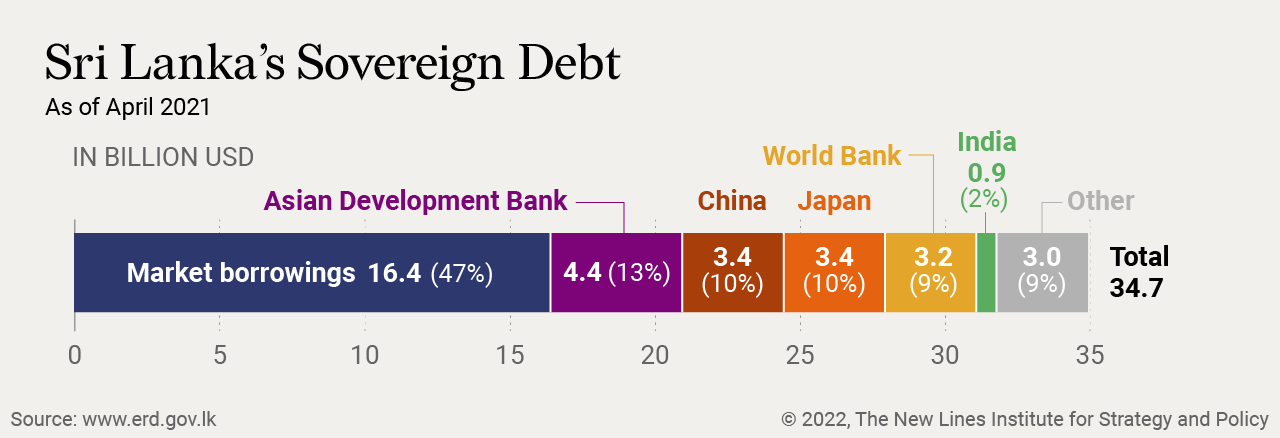

The economic turmoil in Sri Lanka has fueled much speculation concerning its future and how the relatively prosperous country could have experienced such an unexpected socioeconomic meltdown. Sri Lanka currently owes over $50 billion to its creditors, which include countries like India, China, and Japan, as well as private bondholders. With the Sri Lankan economy nearing collapse, accusations of Chinese debt-trap diplomacy again resurfaced. Such accusations are, however, exaggerated, given that China holds only 10 percent of Sri Lanka’s debt. Moreover, given its current economic and political crisis, even China would be reluctant to make further financial investments there, despite its strategic value.

The Sri Lankan government has reached an initial agreement with the International Monetary Fund for a $2.9 billion loan for 48 months. While the IMF loan would not be enough by itself to address Sri Lanka’s economic woes, it would help restore some confidence in the Sri Lankan economy and provide reassurance to other multilateral and bilateral agencies and private-sector lenders to also come to the country’s aid. Yet the Sri Lankan government will have to exercise significant financial prudence and austerity for the foreseeable future, no matter which political configuration comes to the fore. This prolonged austerity drive may undermine chances of the Rajapaksas staging another comeback, given that their political dynasty has now lost the support of the business community and is the subject of widespread anger.

The largely peaceful political protests that led to the removal of the Rajapaksa government also brought together members of different ethnicities and religions, a positive sign in terms of forging a much-needed sense of national cohesion. However, the situation remains unpredictable. It is just as possible that the return of Gotabaya Rajapaksa may be the first step in another attempt by the Rajapaksa brothers to again access power by using a blend of repressiveness and ethnonationalist policies aimed at placating the Sinhalese majority.

The current political imbroglio has also stoked fears that Sri Lanka’s government could be taken over by the a military. Since Sri Lanka became independent in 1948, there have been three attempted military coups, and the military has played a prominent part in the 26-year civil war. It also has been intensively involved in the postwar reconstruction of Tamil-held territories and the subsequent militarization of the state machinery via the appointment of retired military personnel to key civil administration posts under Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s presidency. Given the military’s outsized role in the political economy of the country, the fear that it could assume political control is not without substance.

Times will be hard for the Sri Lankan citizenry at large for the foreseeable future. However, not everyone will feel the brunt of the ongoing economic downturn equally. Marginalized groups invariably feel the impact of a financial crunch more than the better off. After the end of the civil war, the Sri Lankan government received several loans from the IMF as well as bilateral support from Western governments to help rebuild the war-torn north. While much of this aid was routed through the Sri Lankan government, leading to suspicions of corruption, these incoming funds did enable rebuilding infrastructure across the Jaffna peninsula and the financing of small agricultural projects, and provision of micro-entrepreneurship loans for Tamils in the devastated town of Kilinochchi, once the epicenter of LTTE resistance. Given the current economic situation, it is possible that rehabilitation of Tamil areas will again be placed low on the list of priorities, which in turn may reignite ethnic restiveness, especially since the underlying causes for Tamil disgruntlement remain unaddressed.

How the U.S. Can Help Sri Lanka

While contending with the current turmoil in Sri Lanka implies dealing with complex challenges on multiple fronts, this is a time of flux that enables the U.S. to reconsider how to move forward with this bilateral relationship. Some argue that the present situation is an opportune time for the U.S. to push other members of the Quad (Australia, India, and Japan) to step up aid for Sri Lanka in an effort to prevent it from becoming more beholden to China. This does seem like a good time for the U.S. to enhance its support for Sri Lanka, but it is imperative that American policymakers go beyond viewing Sri Lanka only through the lens of great-power competition.

The U.S. and regional powers like India can play a significant role in supporting Sri Lanka during this moment of fragility and help bring the Sri Lankan state back from the brink of collapse. However, any support provided to Sri Lanka should be motivated by the aim of helping ease the plight of ordinary citizens and to circumvent the increasingly majoritarian and security-dominated narrative that has become entrenched in the national discourse over the past two decades. The U.S. can integrate Sri Lanka into its Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment Initiative, which aims to mobilize $600 billion by 2027 to provide a more transparent and sustainable source of funding to countries within the Global South that are becoming increasingly dependent on Chinese development financing.

The U.S. can also harness other multilateral and bilateral aid to Sri Lanka to prioritize policies that help the poor instead of primarily relying on unbridled market mechanisms to secure macroeconomic stabilization, which often exacerbates inequalities. Such nuanced support would additionally serve the goal of lessening Sri Lanka’s growing reliance on Chinese loans. Bilateral American aid to Sri Lanka should pay specific attention to investing in measures that safeguard the interests of minorities, promote political and cultural tolerance, and address the long-neglected rehabilitation of the Tamil-dominated north.

Religious tensions are rising within countries across South Asia, which can worsen already fraught relations between neighboring countries. The intolerance of a religious majority against any of the region’s minority religions in one country can have dangerous effects across borders. Drawing on its rich heritage of religious diversity, where Hindus, Muslims, Buddhists, and Christians have long coexisted in relative harmony, Sri Lanka needs to infuse a sense of coexistence within the national policy, which can offer a model for emulation by other regional countries. Sri Lanka’s spontaneous and widely supported protest movement has not only succeeded in the overthrow of the Rajapaksa government but also has provided a unique opportunity to build on this heightened political awareness to push for meaningful reforms to ensure accountability and greater inclusivity with governance structures.

The United States can support Sri Lanka in bolstering governance mechanisms to stem the corrosive tide of majoritarianism and deter authoritarian leaders from stoking division to grab political power. Conversely, ignoring the current moment of flux within Sri Lanka could lead to long-term adverse effects. Leaving Sri Lanka on its own to undergo a stringent fiscal austerity program could usher in an era of increased illiberalism and ethnonationalism, which would not be good news for either Sri Lanka or the U.S. goal of exerting a positive and stabilizing influence in South Asia.

Dr. Syed Mohammed Ali is a professor of anthropology, international development, and human security courses at Johns Hopkins, Georgetown, and George Washington universities. Dr. Ali has two decades of experience working on major international development challenges including governance problems, issues of marginalization, and natural and man-made disasters. Ali is the author of Development, Poverty and Power in Pakistan: The Impact of State and Donor Interventions on Farmers (Routledge, 2015).

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not reflective of an official policy or position of the New Lines Institute.