Introduction

Sanctions constraining Russia’s ability to wage war will limit its ability to engage in human rights violations and atrocities, such as attacks on pediatric hospitals. However, while Ukraine’s Western allies have spent billions of dollars supplying Ukraine with the most sophisticated air defense systems in their arsenals, essential components supplied by Western companies are still commonly found in Russia’s most advanced precision-guided long-range munitions. From its February 2022 invasion of Ukraine through April 2024, 54 recorded attacks on hospitals serving children in Ukraine have been attributed to the Russian military. Pediatric hospitals in Ukraine can be protected from Russian missiles with help from the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, the European Union, Japan, and Taiwan, all of which have placed sanctions on the exportation of specific dual-use technologies to Russia, including microchips that can be used to guide missiles to their intended targets.

On July 8, 2024, one of those advanced Russian munitions, a Kh-101 air-launched cruise missile, struck the Okmatdyt pediatric hospital in Kyiv, Ukraine’s largest such facility. More than 100 people were injured in that strike, which was part of a barrage across the country that killed at least 47 people, including 11 in the capital. Open-source video evidence as well as components of the weapon found by the Security Service of Ukraine confirmed that a Kh-101 had hit the hospital. The identification is particularly important to note as the Kh-101 is manufactured with at least 18 U.S.-manufactured technological components out of 28 total Western components. Russia cannot create a Kh-101 without using 31 components imported from outside the country. It sources these parts through third parties that act as brokers, thus helping Russia avoid bans on technology sales.

Texas Instruments Corp. and Analog Devices

Companies such as Texas Instruments receive tax credits and other benefits paid for by U.S. taxpayers through federal subsidies. Components these companies manufacture that are affected by the sanctions are sold to “front companies” in other countries that resell the components to Russia. The Russian government has imported them through entities in the Middle East, China, Malaysia, Taiwan, and the Philippines. U.S. taxpayers are also funding the expensive air defense systems such as the Patriot and NASAMS that the United States has provided to Ukraine to help protect it from these very same missiles.

Without additional air defense support for Ukraine or a tightening of the sanctions regime, Ukraine is left insufficiently protected from incoming ballistic missiles. Even if stricter sanctions were enacted, Russia would still be able to produce ballistic missiles, albeit ones with lesser accuracy. Had more air defense systems been in place in Kyiv on July 8, it is possible the hospital attacks may not have hit their targets. Ukraine had made repeated requests before that date for more U.S. air defense systems, but it was not until the day after the hospital bombings that the White House declared that five more systems would be supplied. Ukrainian President Volodymir Zelenskyy has deemed this number insufficient, requesting an additional 25 systems to more fully protect Ukraine, especially civilian infrastructure in major population centers where the majority of the country’s healthcare network is situated.

Russia’s Long History of Targeting Healthcare Infrastructure

The strike on Okmatdyt was well documented by Western media. But less widely reported was damage sustained the same day by two other healthcare facilities in Kyiv. The Children’s Center for Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery, situated near the Okmatdyt hospital, sustained heavy damage in the same strike. Another Russian missile hit a private medical clinic in Kyiv called Adonis. It killed two doctors and five patients. These attacks are not outliers. A consistent uptick in attacks on Ukrainian healthcare was recorded in the first months of 2024. Since Russia’s 2022 invasion, the World Health Organization recorded 1,365 attacks targeting healthcare facilities in Ukraine, with damage occurring in 630 of them. Sixty percent of all attacks on healthcare internationally occur in Ukrainian territory.

Attacking healthcare infrastructure is not a new tactic for the Russian military. During its intervention in Syria in support of the regime of President Bashar al-Assad, the Russian military deliberately and systematically targeted healthcare infrastructure. By 2019, Russian attacks on healthcare facilities became so prolific that medical nongovernmental organizations operating in Syria refused to provide the coordinates of their facilities to the U.N., understanding that when the U.N. shared these coordinates with Russia as part of its deconfliction program, they would become targets of the Russian air force. Attacking healthcare infrastructure was a key part of the Russian and Syrian governments’ strategy for making life in the rebel-controlled areas untenable. The subsequent lack of international outrage about that practice opened the door for Russia to replicate those tactics in Ukraine.

Although international law forbids attacks on hospitals, whether they are treating soldiers or civilians, the Russian military has consistently disregarded those restrictions. Russia’s response to the bombing of Okmatdyt was replete with disinformation, including false allegations that Ukrainian soldiers were being treated at the hospital and that the Ukrainian military was using the facility to store missiles. These attacks diminish the capacity of the wider Ukrainian healthcare infrastructure – specifically, in this case, the ability of Ukrainian children to access pediatric healthcare. Dr. Andrii Maxymenko, the chief medical doctor of the Children’s Center for Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery, reported that while the hospital would typically have conducted 120 surgeries a month, after the July 8 strike, that capacity was estimated to have been reduced by two thirds. In the longer term, this side effect of the missile strike could well result in the loss of young Ukrainian lives.

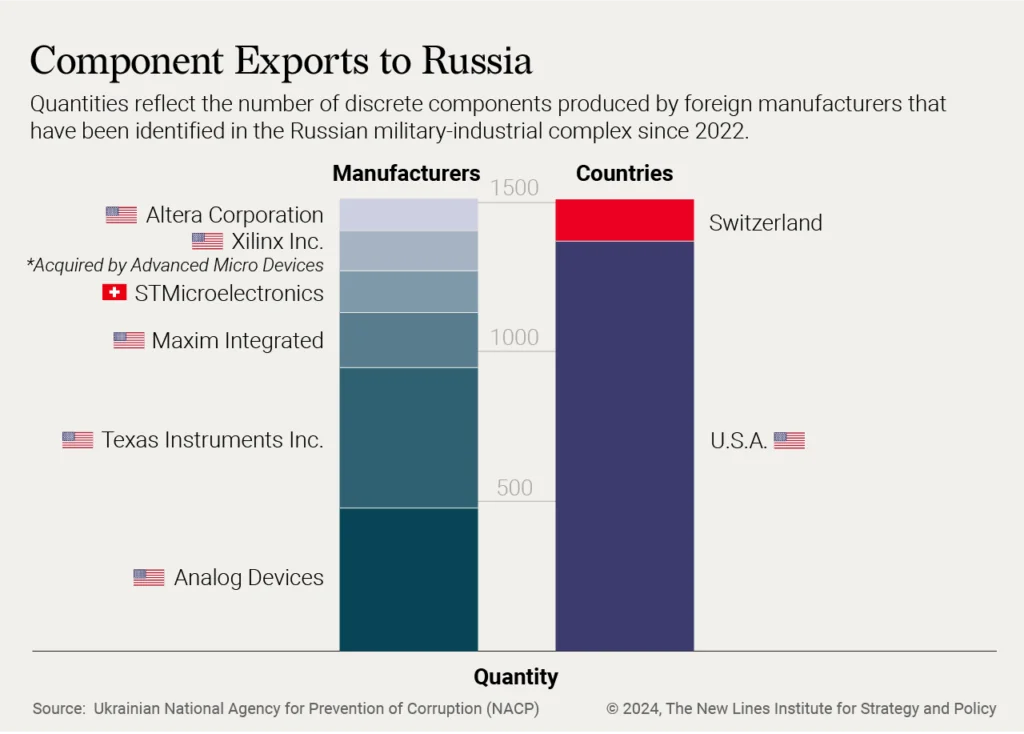

While Russia regularly targets healthcare infrastructure in Ukraine, it has also used missiles containing Western components against other civilian targets. In July 2022, 27 people were killed when 3M-14E Kalibr cruise missiles struck Vinnytsia, Ukraine. Like the Kh-101, those missiles and others in the Russian arsenal such as the 9M727 Iskander ballistic missile are known to contain parts from Western companies. In August 2022, Ukrainian officials discovered several microchip technologies manufactured by Western companies in an unexploded missile in Western Ukraine, including ones made by Texas Instruments Corp.; the Intel Corp. subsidiary Altera; and Xilinix, which was purchased by Analog Devices Inc. in 2022. On Aug. 19, 2023, an Iskander-M ballistic missile was used to strike a theater in Chernihiv, leaving seven dead, including a 6-year-old girl. In addition to the deaths, the attack, which came as holiday revelers had gathered, injured 180 people, 46 of whom had to be hospitalized immediately.

Such events are entirely preventable. Technological components from Western companies often fall outside of the strict sanctions regime imposed on the Russian Federation in 2022 by the United States and European allies. Of the 450 Western parts found within weapon systems used by Russia in Ukraine, 318 of them had been made by companies in the United States. Texas Instruments had manufactured 51 of those 450 parts, the largest share of components by a U.S. company.

U.S. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan has lauded sanctions as an essential component of the foreign policy toolkit. But the current U.S. sanctions regime against Russia doesn’t cover older technology – parts that could be labeled “low tech” – an omission that the Kremlin exploits. Technological flows from the West help Russia maintain a consistent supply of components it must have to create highly accurate long-range munitions despite Western sanctions. For instance, the Kh-101 that hit Okmatdyt had been made just a few weeks or even days prior to the attack. To shut off that supply, the current sanctions regime requires an update addressing older technology – parts that that are easily accessible or reverse-engineered.

Cruise missiles like the Iskander-K and the Kh-101 are designed to fly at low altitudes to evade air defense radar, with the ability to alter course built into the missile’s avionics. Technology manufactured by companies such as Texas Instruments and Analog helps to ensure that such munitions can accurately strike an intended target. Russian import data showed that over an eight-month period in 2022, Russia received $50 million worth of material from Texas Instruments and $89 million worth of technology from Analog. Texas Instruments said it’s possible that Russia received those components before sanctions were enacted. In the first five months of 2023, over 200 Russian companies received over 17,000 Texas Instruments said it’s possible that Russia received those components before sanctions were enacted. In the first five months of 2023, over 200 Russian companies received over 17,000 Texas Instruments microchips through intermediaries., including two Hong Kong based companies now under U.S. sanctions. Texas Instruments maintains that it did not sell chips directly to those companies and did not support Russia’s military use of them. The U.S. government may choose to compel companies such as Texas Instruments to consider how the current supply chain permits their microchips to be used in missiles used to attack Ukrainian territory and change their policies accordingly.

Texas Instruments reported revenue of $3.82 billion in the second quarter of 2024, with a net income of $1.13 billion. A review of the publicly available data suggests that Texas Instruments shareholders have prioritized profits over a more thorough investigation of where the company’s technological components end up and how they are put to use. A minority shareholder group, the Friends Fiduciary Corporation, unsuccessfully pushed a proposal for a greater review of the company’s supply chain management at Texas Instruments’ annual stockholders meetings in 2023 and again in 2024. Shareholders voting at both meetings rejected the proposals by a large margins.

In addition to Texas Instruments, Advanced Micro Devices, Analog and Intel were also called to submit information to the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations to determine how their components were ending up in Russia despite U.S. export controls. This follows the internal debate among Texas Instruments shareholders, some of whom fear a lack of internal oversight would harm the company’s reputation.

Beyond advising that the proposal be rejected, the company’s directors sought guidance from the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission whether they would face enforcement action if they prevented the proposal from coming up for a vote at the 2024 meeting. The agency replied, in part:

“The Proposal requests that the board commission an independent third-party report on the Company’s due diligence process to determine whether customers’ misuse of its products expose the Company to human rights and other material risks. We are unable to concur in your view that the Company may exclude the Proposal under Rule 14a-8(i)(7). In our view, the Proposal transcends ordinary business matters and does not seek to micromanage the Company.”

In the absence of internal policing, the federal government must hold companies under its jurisdiction to account. This requires stricter sanctions to be applied to component sales to Russia. While the supply chains that allow Russia to obtain such parts may originate as legitimate sales that follow the law, it is patently obvious that some companies understand where their products will ultimately end up. There are signs that the White House recognizes the extent of the problem: U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken has discussed with Chinese leaders the need to keep advanced semiconductors sold to Chinese companies from being resold to Russia. Indeed the U.S. has imposed secondary sanctions on Chinese entities that have supplied the restricted components to Russia. While noting such Chinese assistance to Russia, Blinken nonetheless endorsed greater cooperation between the U.S. and China to improve military communications. Further sales to Chinese companies that circumvent sanctions directly leads to the destruction of civilian targets by aiding Russian missile production. With 90% of microelectronics weapons components coming through China in 2023, the time to strengthen sanctions is now.

Even if members of Congress have the political will to levy further sanctions there are still ways to circumvent them. Microchips are small, with hundreds easily fitting into a few backpacks. That size alone creates an impediment to sanctions enforcement. Much like illicit arms or drug trafficking, the ease of microchip smuggling would make it alluring for black market dealers. This is doubly so given their legitimate legal status, which reduces risk far beyond that of smuggling intrinsically illegal or more heavily controlled goods such as narcotics or firearms.

All of these issues require creative thinking on the part of sanctions designers, but policymakers in the West should be motivated by the clear impact effectively enforcing such sanctions would have on Russian missile production. Gen. Krylo Budanov, head of Ukrainian Military Intelligence, was clear about how to keep Russian precision-guided armaments out of Ukrainian airspace in remarks at a forum on Feb. 5, 2024:

“As my colleague says, everyone works together to avoid sanctions, (but) this is not enough. I can tell you absolutely, directly, because all of them see rockets (it) definitely means this is not enough. The question is much deeper here. What are the secondary sanctions and whether governments of many countries are ready to hit their companies that sell (what is) very often not strictly military equipment … The question is completely open, but we are working, this is what we do on the international stage. As they say, what we do with the enemy is that we strike at the places where they store this equipment.”

Budanov is correct. The problem of sanctions evasions enabling Russian missile production has a solution if the political will to enact it can be found. Ukraine’s survival – and the survival of its healthcare sector – may depend on prioritizing international human rights over potential profits. Like many other companies, Texas Instruments has its own political action committee to protect and enhance its corporate profitability. While corporations will seek to influence those on Capitol Hill not to put further restrictions on exports, international security and the protection of pediatric healthcare institutions mandates a stricter enforcement regime be put into place.

Policy Recommendations:

There are political solutions available to U.S. lawmakers regarding the attacks on pediatric healthcare in Ukraine. Four countries are currently considered state sponsors of terrorism under the U.S. State Department’s designation: Cuba, Iran, North Korea, and Syria. The designation provides for heavy penalties for any individual or business doing business with the sanctioned state. Additionally, defense sales exports and dual-use items are restricted under the state sponsor of terrorism designation. While Syria was designated thusly in 1979, additional sanctions were enacted because prior legislation did not adequately restrict the Assad regime’s capability to utilize third-country actors to evade sanctions. The Syria Accountability and Lebanese Sovereignty Restoration Act of 2003 banned the sale of dual-use items and the export of materials other than food and medicine to Syria. In 2019, the Caesar Syria Civil Protection Act was passed to give the Treasury Department the discretion to determine if the central bank in Syria is engaging in money laundering and mandates further documentation regarding transactions. In 2023, under the Caesar Act, businesses assisting Assad and Hezbollah were penalized. Similar legislation to the Caesar Act is required for Russia, given that it has not been designated a state sponsor of terrorism. This is particularly important since the Foreign Sovereignties Immunities Act is not applicable to Russia due to the passage of Rebuilding Economic Prosperity and Opportunity for Ukrainians Act.

Just as Syria was sanctioned multiple times before finally being labeled as a state sponsor of terrorism, multiple sanctions were placed on North Korea prior to its 2017 designation as a state sponsor of terrorism. The Iran, North Korea and Syria Nonproliferation Act, enacted in 2000, has been utilized multiple times, including in 2017 when the State Department used it to sanction Chinese officials and entities accused of aiding and abetting the country in circumventing sanctions. Other key legislation included the North Korea Sanctions and Policy Enhancement Act, which passed in 2016, granted the president a number of discretionary powers when choosing persons and entities to sanction, and to make accommodations for humanitarian aid to be provided to North Korea. Both countries had been subject of additional secondary sanctions that tightened export controls before the state sponsor of terrorism designation was applied.

Presently Russia imports more semiconductors than before the 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Texas Instruments products have reached Russia via sales by companies in multiple other countries, including but not limited to Taiwan, Turkey, Monaco, Thailand, Philippines, Malaysia, China, Hong Kong, and the United Arab Emirates. Many of the countries that serve as conduits for microchips to Russia are not directly hostile, and may even be friendly, to the United States. The large volume of trade occurring in violation of these, and other sanctions makes it necessary for the Treasury and State departments to increase staffing levels to adequately police it, requiring greater congressional appropriations. Lawmakers should provide increased funding to hire more enforcement staff and provide more resources for the State Department’s Directorate of Defense Trade Controls through the International Traffic in Arms Regulations Office and for the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control. Furthermore, the enforcement of already enacted sanctions will require increased appropriations to provide additional staffing for both the Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network and the Department of Justice.

Legislation also should be adopted to tighten the current sanctions regime. If Congress does not designate Russia as a state sponsor of terrorism as set forth in legislation filed in June by Sens. Lindsey Graham and Richard Blumenthal, then equivalent measures should be created. Secondary sanctions should be implemented, expanding targeted persons and entities and encouraging multilateral participation among states.

Whistleblower benefits should be enhanced. Laws like the Anti-Money Laundering Whistleblower Improvement Act, which was passed in late 2022, enhance incentives for people, including company insiders willing to risk their jobs, to provide the government with actionable information about sanctions evasion and money laundering activities by corporations and other entities. While an individual reporting such malfeasance risks being fired from a job, legislation like this, giving them a significant percentage of any financial judgement or settlement a company pays in such cases, could motivate a worker to help the government enforce sanctions law.

The U.S. should reinstate the Coordinating Committee for Multilateral Export Controls (CoCom), a Cold War-era entity designed to limit military and dual-use technology exports to states within the Soviet sphere of influence. The U.S., United Kingdom, and France worked out an agreement in 1949 as to how they would work together to coordinate export controls and then expanded their conversation to include other European states. The result was an arrangement by which the United States, in partnership with other NATO members and other partners including Japan, would place restrictions on strategic exports to former Soviet states and to China. Spain and Iceland did not participate in the original CoCom. In later years, Spain and Australia joined CoCom, enhancing the organization’s stature internationally. In total, 17 states, led by the United States eventually worked together to restrict strategic exports to former Soviet states and China. As a nontreaty entity, CoCom’s member states were not required to implement all agreed-upon export controls, with the U.S. having a greater capability of enforcing restrictions than other member states. A new, revised version of CoCom should receive funding from Congress as well as from the United Nations.

CoCom ceased to function in 1994, and a successor organization called the Wassenaar Arrangement on Export Controls for Conventional Arms and Dual-Use Goods and Technologies came into existence. Access to participation in the Wassenaar arrangement is open, with membership including Russia. Enforcement of export controls under the Wassenaar Arrangement is entirely volitional. CoCom required unanimous approval of its participants to approve which entities received export control licenses, whereas the Wassenaar Arrangement lacked a review and approval process for the licenses. The resulting ineffectiveness of the Wassenaar Arrangement makes revisiting and resurrecting CoCom a better option for aiding in international export controls.

The U.S. Commerce Department’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) has banned international manufacturers from exporting U.S. technology and software using the Foreign Direct Product Rule (FDPR), thus mandating international compliance with U.S. export regulations. However, export controls are not presently well coordinated internationally. This can be fixed by allowing for harmony across various jurisdictions through the reconstitution of CoCom to ensure that outside of the United States, the impact of the FDPR is maximized.

National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan has stated that the Biden administration wishes to place the needs of U.S. national security over the profitability of U.S. corporations. To this end, a reconstitution of CoCom would provide a forum by which states can communicate clearly regarding export controls, working in collaboration to diplomatically address the concerns of other stakeholders states whose market profits may be diminished by the levying of export controls.

Legislation that limits the ability of attorneys to help clients skirt federal financial restrictions on the sale of assets, as put forth in a previously proposed bill dubbed the Enablers Act, would assist in closing a loophole in the Banking Secrecy Act, and would mandate that the legal practice, like banking institutions, be subject to anti-money laundering restrictions. It is essential that lawmakers mitigate Russia and its enablers to engage in regulatory arbitrage. The United States and all allies should be alert to efforts by Russia and its allies to undermine global financial networks. All governments have a duty to act as gatekeepers in the enforcement of sanctions. With such appropriations and proposed legislation enacted, events such as the attacks in Kyiv July 8 on pediatric healthcare institutions will become far rarer.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of the New Lines Institute.