The Hazara Genocide: An Examination of Breaches of the Genocide Convention in Afghanistan since August 2021

Executive Summary

This report makes a legal assessment of acts targeting the Hazara in Afghanistan. This assessment examines the most recent attacks against the community and the ongoing dire situation, since the Taliban takeover in August 2021. It investigates whether the recent and ongoing attacks against Hazaras, carried out by various actors including the Islamic State-Khorasan Province (“IS-KP/Daesh”), the Taliban, and the Taliban-backed Kuchis, constitute genocide as per Article II of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. The report also considers historical treatment of the Hazara by multiple actors, including during the 19th and 20th centuries. The report maps the situation, considering the elements of the crime of genocide, and engages with the question of state responsibility under Article I of the Convention.

This report’s analysis reveals a reasonable basis to believe that the targeting of the Hazara in the past few years, for which the Taliban and IS-KP/Daesh have predominantly claimed responsibility, meets the legal criteria for the crime of genocide under Article II of the Convention. While the historical attacks on Hazaras in the 19th and 20th centuries cannot be analyzed in the same way, for reasons detailed in the full report, they help to clearly establish the long-standing persecution and targeting of the community and are key for establishing state responsibility.

This report finds that there is a reasonable basis to believe the attacks on Hazaras satisfy the actus reus and mens rea elements of genocide. With respect to the actus reus requirement, the attacks on Hazaras amount to prohibited acts under Article II (a) (killing members of the group), Article II (b) (causing serious bodily or mental harm), and Article II (c) (inflicting conditions calculated to bring about physical destruction). With respect to the mens rea requirement of dolus specialis, the necessary intent goes beyond merely committing the prohibited act – it must also reflect a deliberate aim to destroy the group, in whole or in part.

The atrocity crimes discussed in this report require legal responses towards justice and accountability – including individual criminal responsibility of those responsible, but also state responsibility, and responsibility of the de facto authorities of Afghanistan. Given that the de facto authorities of Afghanistan are involved in the violation of the Genocide Convention, other states parties must act upon the duties under the Genocide Convention – to protect and “employ all means reasonably available to them” to protect Hazaras from further genocidal acts in Afghanistan and to punish – by ensuring justice and accountability.

Introduction

The human rights crisis in Afghanistan following the Taliban’s seizure of Kabul in August 2021 has garnered renewed global attention, particularly in relation to the Islamic emirate’s repressive regime and draconian laws vis-à-vis Afghan women and girls. On Jan. 23, 2025, the International Criminal Court’s (“ICC”) Office of the Prosecutor filed applications for arrest warrants against two senior Taliban leaders, arguing that these individuals “bear criminal responsibility for the crime against humanity of persecution on gender grounds, under article 7(1)(h) of the Rome Statute.” In July 2025, the two arrest warrants were ultimately approved by the Pre-Trial Chamber.

While such proceedings indicate progress, the ICC and other relevant international bodies have been largely silent, and/or acted too late with respect to other long-standing and serious human rights violations in Afghanistan, including deliberate attacks against the Hazara, which have resulted in thousands of deaths and injuries in recent years. This report undertakes a legal assessment of the targeting of the Hazara in Afghanistan. In particular, it investigates whether the recent attacks against the Hazara constitute genocide as per Article II of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (“Genocide Convention” or “Convention”), and mirrored in Article 6 of the Rome Statute of the ICC. Moreover, the report considers the question of state responsibility under Article I of the Convention.

This report’s analysis reveals that there is a reasonable basis for believing that the targeting of the Hazara by the Islamic State-Khorasan Province (“IS-KP/Daesh”) and the Taliban meet the requisite legal criteria for the crime of genocide under Article II of the Convention. These attacks have involved the killing of members of the group, the infliction of serious bodily and mental harm, and the imposition of conditions of life calculated to bring about the destruction of the groups – all of which is conduct prohibited under Article II of the Convention and, when paired with the specific intent to destroy, will amount to the crime of genocide.

The atrocity crimes discussed in this report require legal responses towards justice and accountability – including individual criminal responsibility of those responsible, but also state responsibility, and responsibility of the de facto authorities of Afghanistan. Given that the de facto authorities of Afghanistan are involved in the violation of the Genocide Convention, the Afghan state’s breach of its international responsibility, other states parties must act upon the duties under the Genocide Convention – “employ all means reasonably available to them” to protect Hazaras from further genocidal acts in Afghanistan, and to punish – by ensuring justice and accountability.

Prohibited Acts Against Hazaras

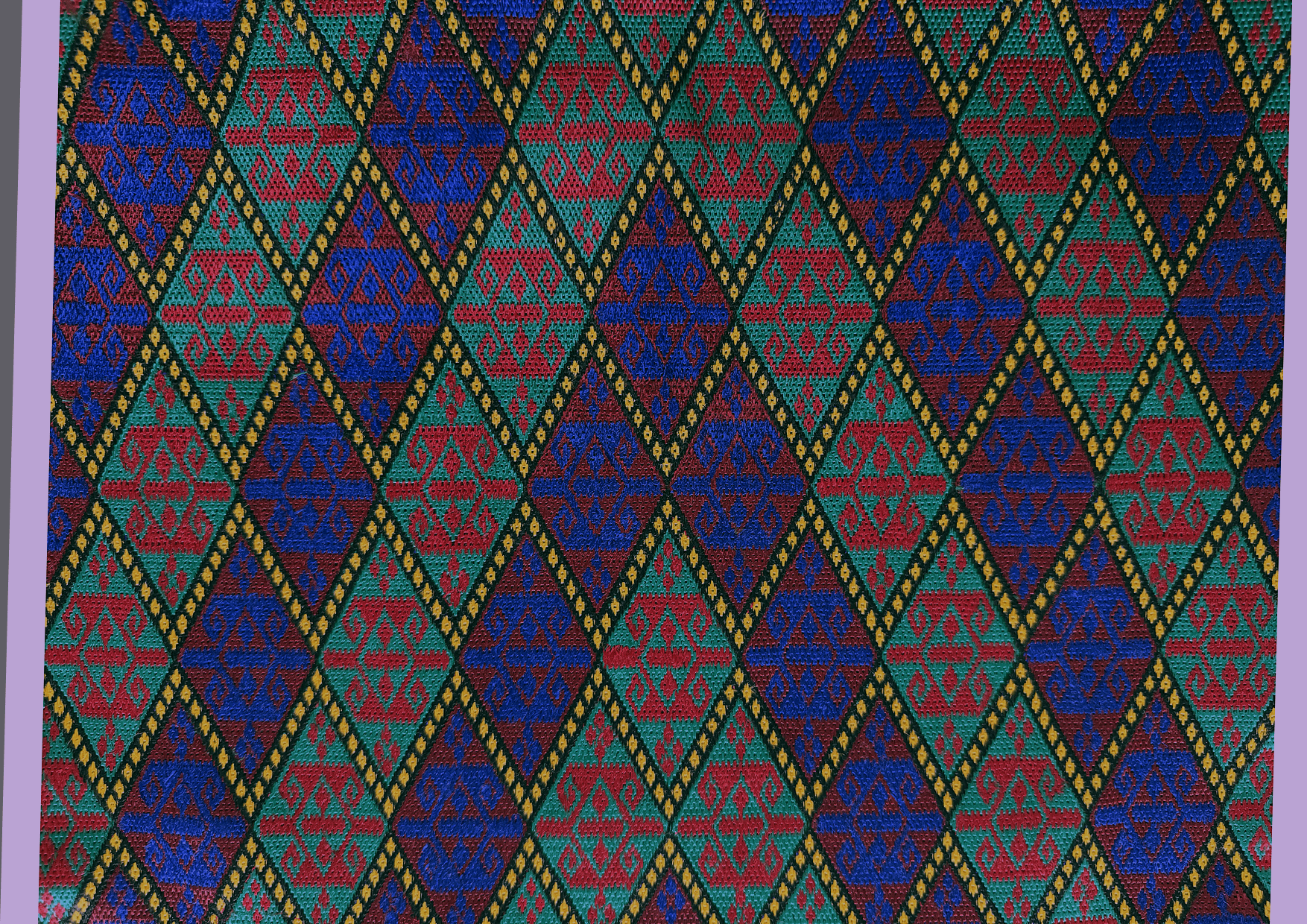

Protected group: Article II of the Genocide Convention applies to members of a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group. The Hazaras are identifiable by their Asiatic features, distinct Farsi dialect (Hazaragi), and mainly Shia faith in a predominantly Sunni country. Afghan governments and constitutions have also recognized the Hazaras as a separate ethnic group. Accordingly, the Hazaras fall within the ambit of Article II by belonging to an ethnic group by virtue of their shared culture, language, and religion.

Furthermore, the Hazara Shia could be treated as a religious group. The majority of Hazara identify with the Shia branch of Islam. As followers of the Shia (Twelver Imami) tradition, Shia Hazaras are recognized as a protected religious group under Article II. Their faith places them in the minority within Afghanistan, where Sunni Islam is the predominant religion. Crucially, the Hazara are often targeted in their places of worship, during their religious ceremonies, commemoration ceremonies, etc. This may indicate the religious element of the attacks. Furthermore, IS-KP/Daesh considers the Hazara Shias as infidels because of their religious identity. The Taliban, as the de facto authority in Afghanistan, have imposed restrictions on Shia religious practices, including limitations on Muharram observances, which mark a significant period of mourning in the Shia faith. These measures include limiting public religious rituals and symbols and confining worship to designated locations approved by the Taliban. Such actions suggest a pattern of religious targeting.

Perpetrators

The two main alleged perpetrators of the vast majority of the attacks against the community are the Taliban and IS-KP/Daesh. IS-KP/Daesh is a Sunni violent extremist group based primarily in Afghanistan and a regional branch of the Salafi jihadist group Islamic State (IS).

Several other groups have been responsible for attacks against the Hazara, including the Kuchis; however, these attacks have received much less attention and, while mentioned in the report, are not analyzed against the legal definition of genocide. Furthermore, some of the attacks are not attributed to any group at this stage, and the lack of investigations may mean that the perpetrators will not be identified. In relation to establishing individual criminal responsibility and/or state responsibility for the crimes against the Hazara, the following points need to be taken into consideration: The atrocities perpetrated by the Taliban and IS-KP/Daesh have been perpetrated over decades, including during the Afghan Republic. The individuals responsible for these crimes could be prosecuted. However, in terms of state responsibility, the Taliban could not be held accountable for these crimes.

- The atrocities perpetrated by the Taliban and IS-KP/Daesh have been perpetrated over decades, including during the Afghan Republic. The individuals responsible for these crimes could be prosecuted. However, in terms of state responsibility, the Taliban could not be held accountable for these crimes.

- The atrocities perpetrated by the Taliban and IS-KP/Daesh since the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan could be prosecuted and could be attributable to the Taliban for the purposes of establishing state responsibility.

- While the Taliban are not recognized as the government of Afghanistan, as the de facto authorities the Taliban could be held to account for their failures under the Genocide Convention.

Policy Recommendations

- The situation of the Hazara requires urgent attention, and this in accordance with the duties to prevent and punish the crime of genocide, including:

- States must consider all means available to them to prevent the genocide, its continuations, etc.; and

- States must ensure that the crimes are investigated and prosecuted including by way of:

- On the international level –

- Establishing a UN mechanism to collect and preserve evidence of the crimes committed in Afghanistan, modelled on IIIM or IIMM;

- Referring the situation of the Hazara to the ICC (as has been done in the case of gender persecution); and

- Initiating proceedings before the ICJ, for the Taliban’s violations of the Genocide Convention.

- On the domestic level globally:

- Initiating structural investigations into the atrocities committed against the Hazara in Afghanistan;

- Initiating prosecutions of those responsible under the principle of universal jurisdiction; and

- On the international level –

- Imposing the Magnitsky sanctions on those responsible for the atrocities against the Hazara.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not an official policy or position of New Lines Institute.

Principal Author

Mehdi J. Hakimi

Mehdi J. Hakimi is a lawyer, scholar, and Editor-in-Chief of the Oxford University Commonwealth Law Journal. He previously served as the John Peters Humphrey Fellow at Harvard Law School and as Lecturer in Law and Executive Director of the Rule of Law Program at Stanford Law School, where he led international initiatives in the Middle East, South Asia, and Africa. Earlier, he chaired the Law Department at the American University of Afghanistan, where he founded the Business Law Clinic and Moot Court Program. He has advised international organizations, governments, and law firms on Afghanistan and comparative legal systems, and his expertise has been cited in court decisions, EU publications, and U.S. congressional reports. His scholarship has appeared in leading journals at Harvard, Yale, Stanford, Columbia, and others. A licensed attorney, Hakimi has worked with global lawfirms and is fluent in Persian/Farsi/Dari, English, Arabic, and French.