On Sept. 3, Sudanese warlord-turned military commander, Lt. Gen. Mohamed Hamdan Daglo, commonly known as “Hemeti,” warned of “sleeper cells” attempting to foil the new interim government and create friction between the army and the public. Hemeti, a member of the recently established Sovereign Council and commander of the notorious government militia known as the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), was speaking about alleged agents loyal to the deposed regime of Omar al-Bashir. However, his statement demonstrates an intention to police the country’s transitional period, which will afford him the opportunity to prevent a transition to civilian rule.

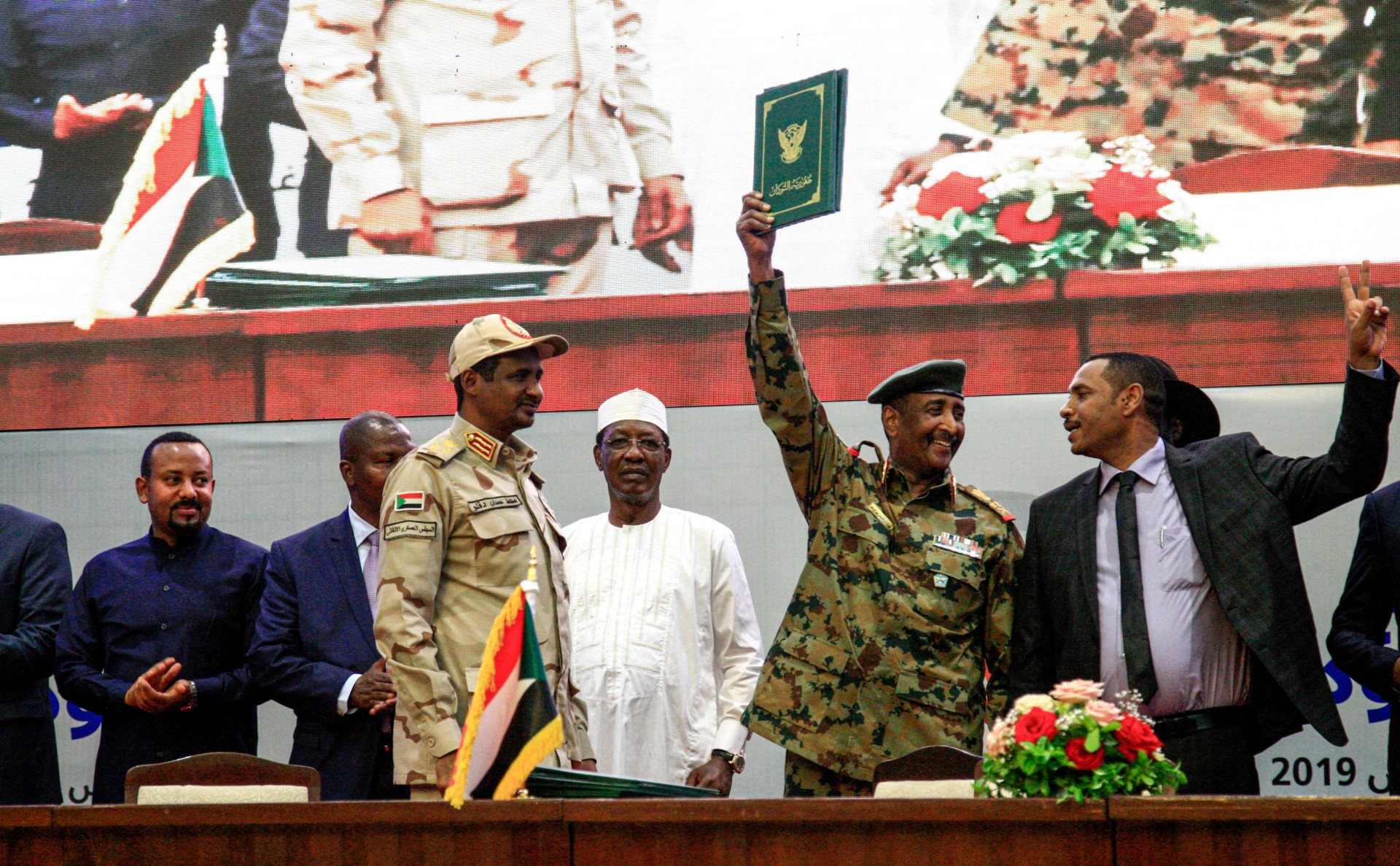

The power-sharing agreement between the army and protest leaders states that a Sovereign Council comprising six civilians and five military officers will rule Sudan for a 39-month transition period. Lt. Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, head of the now-defunct Transitional Military Council (TMC), will lead the Sovereign Council for the first 21 months; then, a civilian will take over until elections in 2022. The deal implies that Sudan will eventually return to civilian rule after the transitional period, though it apparently includes major concessions that would allow the military to maintain the upper hand over a future civilian political dispensation. While military generals involved in the agreement, including Hemeti, have pledged to abide by the deal, serious questions have arisen about their sincerity.

Considering the terms of the new agreement, it is doubtful that Hemeti and other military leaders would have enough power and time to shift the current dynamics and seize power once the momentum of the uprising dies down. Instead, they will likely seek to consolidate power, divide the opposition, and find a way to avoid Sudan having genuine civilian governance.

Hemeti Clears His Own Path

Hemeti is a warlord commanding the RSF, a paramilitary group that grew out of the Janjaweed militia and has been accused of widespread abuses in Sudan. Despite this record, the RSF leader has emerged as Sudan’s most powerful army commander, which represents a major shift in the historical architecture of the country’s armed forces establishment. Hemeti controls most strategic decisions in the country’s domestic political space and represents its interests in foreign policy matters. He also enjoys wide support from regional powers known to favor counter-revolution attempts in Sudan, including the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt. Although he is formally the second in command after al-Burhan, Hemeti is deemed the most powerful military actor capable of leading a counter-revolution in Sudan. For that reason, analyzing his moves and statements is critical. He has already moved to: eliminate his powerful rivals; boost his image as the savior of the popular uprising; and win alliances with different armed rebel groups.

On July 24, Hemeti used information about a military coup plot by the Joint Chiefs of Staff Lt. Gen. Hashim Abdel Muttalab as a pretext to eliminate opponents in both the civil and military sectors and thus consolidate his power over Sudan. Several military officers and political figures, including key members of the Islamic Movement and the National Congress Party of ousted military dictator, Omar al-Bashir. The list of arrestees included prominent figures from the previous regime, including the former foreign minister, the heads of the former regime’s Popular Security and Popular Defense Forces, and the former prime minister.

Multiple sources, including a former high-ranking regime leader, told us that the coup was initially planned for June 30 and that most of the detained military figures had opposed the move and convinced Muttalab not to proceed. One source added that TMC head al-Burhan, who was subordinate to Muttalab, was among those who opposed the coup. Another former regime member said that former regime leaders lacked the centralized leadership necessary for the takeover.

Interestingly, Maj. Gen. Abdul Gaffar al-Sherif — former head of the Security Department within the National Intelligence and Security Services — is the one who coordinated the arrest campaign. Al-Sherif, who had been sentenced to seven years in prison in September 2018 over an alleged major corruption case, was recently released amid the massive protests. The constitutional court persistently denied ordering the release; Hemeti likely had a role, because he has a close relationship with al-Sherif and has the power to free him. Al-Sherif was made Hemeti’s security adviser and was tasked with forming the intelligence department of Hemeti’s RSF.

Repairing the Warlord Image

The foiled coup gave Hemeti an opportunity to boost his image and repair his reputation in the eyes of the international community and the Sudanese people. He took a page from the playbook of Egypt’s Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Sisi and Libya’s warlord Khalifa Haftar: He portrayed himself as a strong military leader who can be trusted to save the transition process and protect the gains of the popular uprising from the deep state.

Improving his image became a necessity for Hemeti following reports accusing his RSF of carrying out the deadly dispersal of the protesters’ sit-in on June 3. Despite defending the use of firm action against “rogue elements and drug dealers” who allegedly infiltrated the protests, Hemeti called for an independent investigation and promised severe punishment to those who crossed the line. Talk of the RSF’s involvement in committing crimes and killing protesters re-emerged following the killing of 10 protesters, including four schoolchildren, during demonstrations in both El-Obeid and Omdurman cities. The anger over the incidents prompted the TMC to announce that nine RSF members were dismissed and detained over the incident.

Seeking Alliances with Rebel Groups

During the negotiations, Hemeti tried to enhance his chances of leading Sudan by attempting to form alliances with powerful rebel groups — mainly the Sudanese People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM), chaired by Abdel Aziz al-Hilu, and the Sudanese Liberation Movement (SLM), led by Abdel Wahid al-Nur. These groups have sizable forces to stand against Hemeti’s 40,000 personnel. They are not members of the Declaration of Forces for Freedom and Change (DFFC), an umbrella group of political parties, armed groups, and civic movements that coordinated the uprising. One opposition source said if the SPLM and SLM had joined the DFFC, they would have weakened Hemeti’s position.

Although Hemeti joined the DFFC delegation on July 27 in trying to convince the SPLM to agree to the initial deal signed by the TMC and protest leaders on July 5, many believe that Hemeti and the TMC had their own reasons for wanting to strike deals with armed rebels. On June 24, Hemeti disclosed contacts with the head of the SPLM and indicated that TMC had already established contacts with other armed groups. Meanwhile, the TMC announced an amnesty for all prisoners from the different rebel groups.

The Sudanese Revolutionary Front, an umbrella group of armed factions based in the Darfur and Blue Nile regions, welcomed the amnesty decision, calling it a “positive step” that could help build confidence between the parties. However, the DFFC criticized the move, describing it as an attempt to divide the opposition alliance. The amnesty decision has slightly distanced the opposition from the Sudanese Revolutionary Front, which has expressed repeated concerns about the DFFC and called for new leadership for the alliance.

Cautions and Recommendations

Hemeti’s maneuvers call into question his intention to abide by the recent deal and allow the country to transition to civilian rule. Pro-democracy protesters are aware of his ambitions and the level of support he receives from regional backers. Thus, they should stop considering the power-sharing deal and the progress in implementing it as a victory. The efforts towards civilian governance will likely continue for years to come.

Hemeti, with his allies in the military as well as his civilian supporters, will likely seek to divide the opposition before attempting to steer Sudan away from the agreement. Although this could lead to renewed turmoil, it would be very difficult for the Sudanese people to regain the momentum of their earlier peaceful protests. This would offer Hemeti and the military establishment an opportunity to ensure that the military retains control of the country’s political system.

To ensure that Sudan does transition to civilian rule:

- The United States and European countries should pressure the Sudan’s military leadership to dissolve the notorious RSF and reintegrate its fighters into other units of the country’s security forces. It is vital to set a timeframe for such a process.

- The United States should pressure European countries to avoid indirectly funding Hemeti through the Khartoum Process, an initiative to control the migration route between the Horn of Africa and Europe. Since Hemeti’s forces dominate the border guard, the European countries should develop a robust mechanism to ensure that the funds sent to Sudan through this initiative do not end up in the RSF’s hands.

- Washington should pressure its allies in the region, particularly Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, to stop funding Hemeti and his RSF for their adventures in Yemen and Libya.

- The United States and European countries should help Sudan’s civilian leaders tackle the challenge of armed rebel groups in the country such that they are unable to align with the RSF.

Amer Mohamad is a Senior Researcher at Integrity Global. Formerly, he worked as a researcher and security analyst focusing on the MENA region. He holds a BSc in Economics, MSc in Banking and Finance, and an MA in Conflict Resolution and Security Studies at Bradford University, U.K. He Tweets at @Amermoh89.

Jihad Mashamoun is a Doctoral Candidate of Middle East Politics within the Institute of Arab and Islamic Studies of the University of Exeter. He authored and co-authored several articles on the Sudanese uprisings. He has a specialty focus on international relations and security within Africa and the Middle East. He holds a BA and MA in Political Science from the American University in Cairo.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of the Newlines Institute.