Since Pakistan obtained the province in 1948, Balochistan has seen numerous uprisings fighting for autonomy and independence. A renewed insurgency in the province has become deadlier and more organized, but regional conflicts like those in Afghanistan, Kashmir, and Sri Lanka have overshadowed it in the minds of Western observers. Although numerous Islamist, jihadist, sectarian, and pro-government militias operate within the province, the current separatist insurgency has been gaining momentum since 2019.

Baloch militants recently have had increased access to a wider range of armaments and have escalated their tactics. Three incidents in 2022 point to this trend. The most recent occurred on Christmas Day, when the Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA) coordinated five bomb attacks in the cities of Turbat, Kahan, Gwadar, and Quetta, killing at least six Pakistani security personnel. On Aug. 1, a Pakistani military helicopter crashed in southwestern Balochistan, killing six senior officers, including a major general and lieutenant general. The Pakistani military attributed the crash to adverse weather conditions; however, the next day, the Baloch Raaji Aajoi Sangar (Baloch National Freedom Front, or BRAS), posted a statement that claimed they used anti-aircraft weaponry to down the helicopter, which the Pakistani government denies. A similar, unprecedented escalation involving Baloch separatists took place on April 26, 2022. Shari Baloch went to the Confucius Institute at the University of Karachi and killed three Chinese teachers and a Pakistani driver in a suicide bombing. Shari Baloch was the first female Baloch suicide bomber, affiliated with the Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA). This suggests a serious increase in the capabilities of Baloch militants, which has led to greater crackdown on the part of Pakistani security forces.

As a result of the BLA’s attack on the Confucius Institute, Chinese teachers left Pakistan and the Baloch people suffered harsh retaliation. For years, Islamabad has carried out a policy informally known as “kill and dump,” which has led to the disappearance of thousands of Baloch activists and other civilians. Since the suicide bombing, reports of abductions by state agencies targeting Baloch people and their supporters have increased. The escalation of the insurgency and the weaponry available to the Baloch insurgency did not arise in a vacuum. Rather, a combination of deteriorating regional conditions, an increasingly repressive Pakistani state, and the consolidation of Baloch insurgent groups have led to a renewed insurgency that has become more potent since 2019.

While the United States and its allies have primarily examined Balochistan through China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) or the presence of the Taliban’s leadership during the recent conflict, the ongoing repression and separatist insurgency demands attention. The repression is itself a human rights concern, and as the insurgency becomes deadlier and more radicalized, it could have potential spillover into the rest of the region. A de-escalation of the separatist conflict will allow Pakistan to focus on its fight against extremist groups of regional interest like its Taliban rebels and the Islamic State-Khorasan Province, and alleviating the repression of the Baloch people will allow Pakistan to start fulfilling its obligations to its own citizens, strengthening democratic norms within the country.

The U.S. and Pakistan’s allies should push for negotiations between Baloch militants and the Pakistani state to de-escalate the violence and militarized presence in the province. In addition, giving a voice and stake to Baloch activists and civilians who have advocated for a more equitable share of resources and economic autonomy can provide an avenue for proper development of the region.

From Annexation to Insurgency

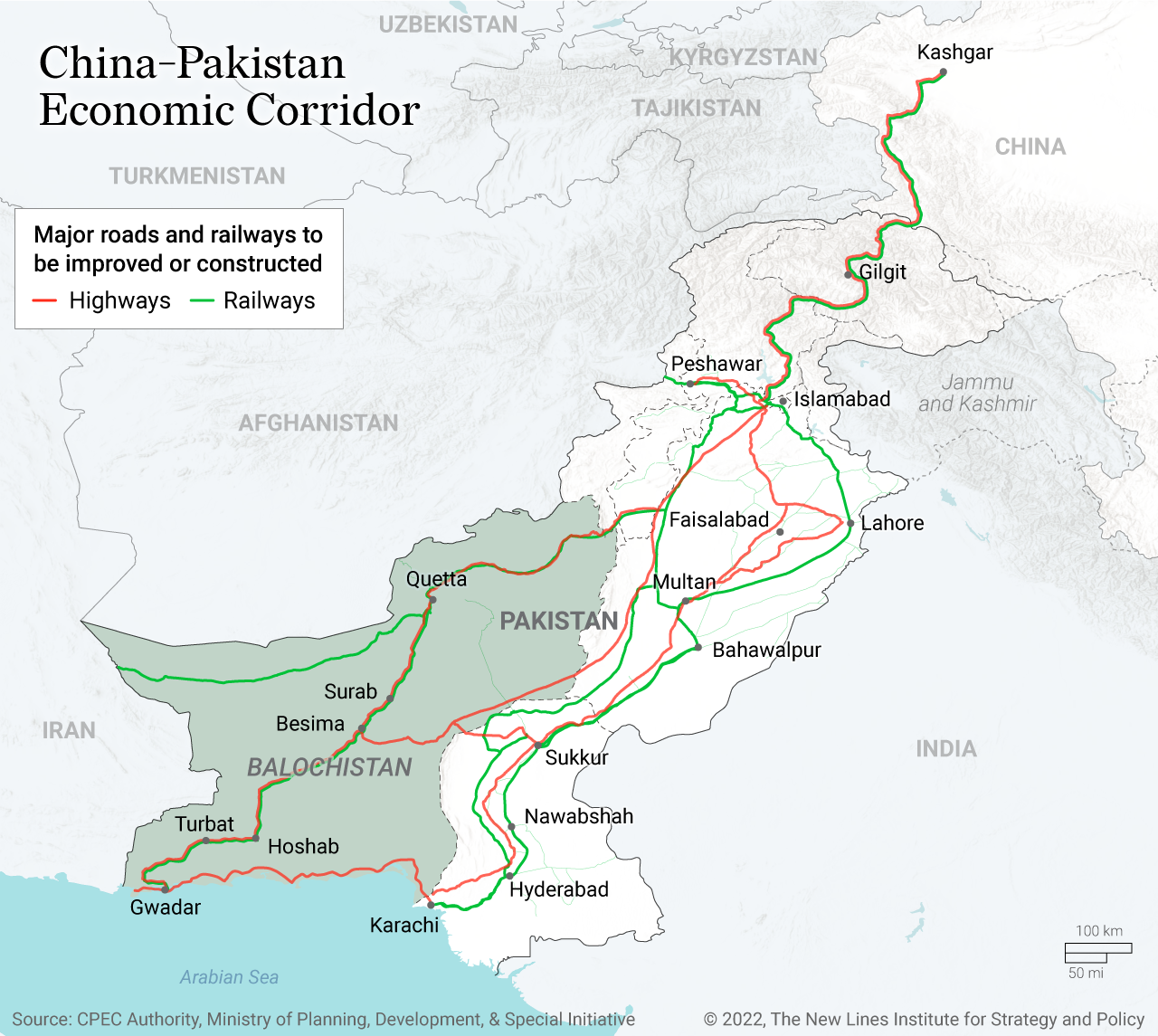

Balochistan is Pakistan’s largest province by area, provides 40% of Pakistan’s gas production, and contains significant natural resources, but it remains the country’s poorest. The economic importance of Balochistan for the Chinese-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) has only added to the enduring political issues between Balochistan and the national government.

Balochistan’s current situation illustrates the importance of understanding its difficult history with the Pakistani state. Prior to partition, the British administered the Baloch of the Afghanistan-Pakistan frontier using the “Sandeman system,” which institutionalized tribal councils, or jirga, and tribal levies among the Baloch as well as empowering local Baloch hereditary chiefs, the sardars, to keep control through financial incentives. This system gave the Baloch a great deal of autonomy to police and govern themselves.

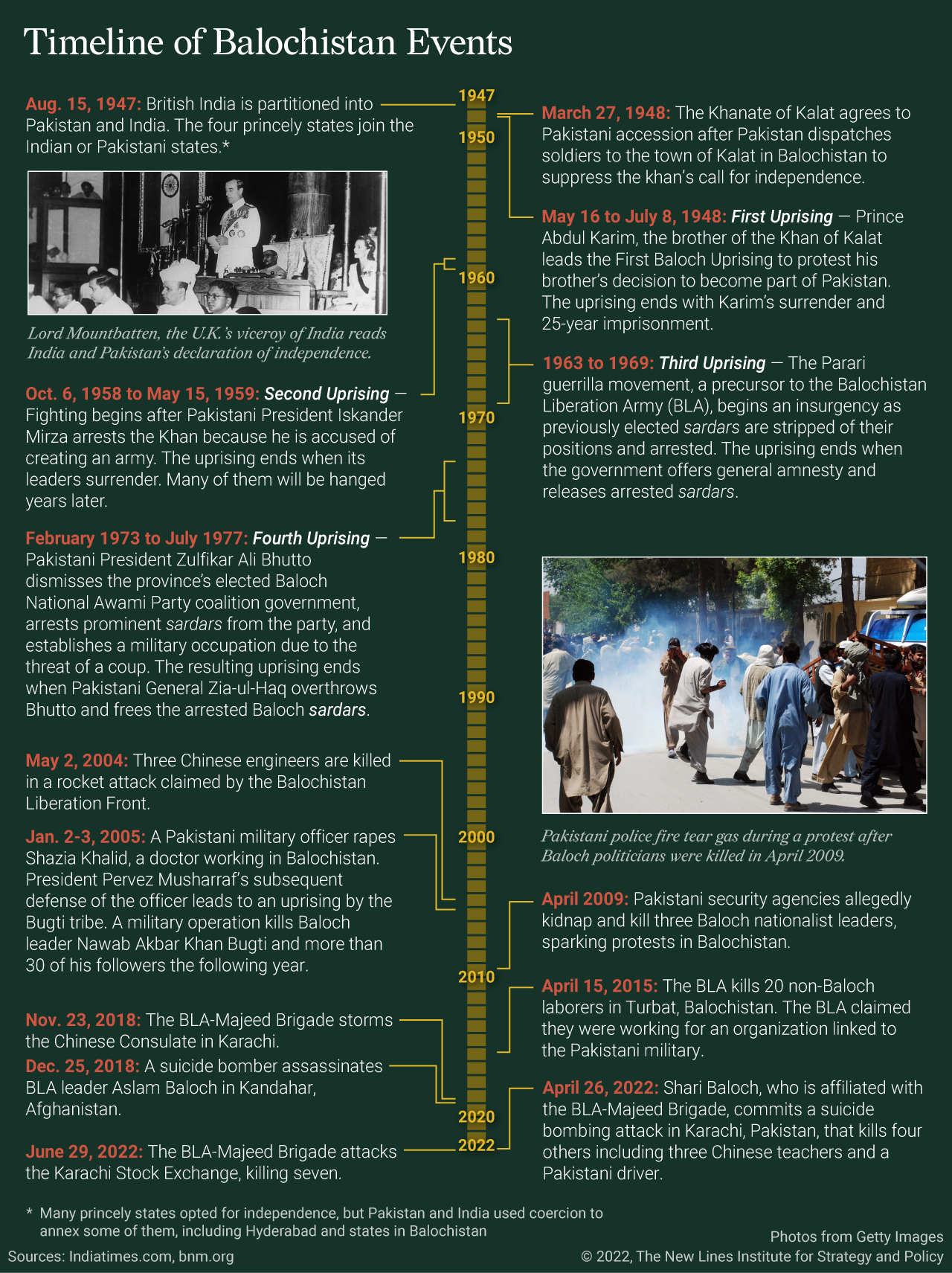

The accession process in Balochistan after partition was fraught: the Khan of Kalat declared independence in August 1947, only to agree to accession in March 1948 after the Pakistani government dispatched soldiers to occupy the region. The agreement launched the First Uprising, which lasted until 1948. Over the next three decades, Balochistan revolted in three more uprisings: from 1958 to 1959, 1963 to 1967, and 1972 to 1977. The insurgencies were responses to Islamabad interfering in Balochistan’s autonomy by declaring martial law, dismissing elected politicians, arresting prominent sardars, and deploying military forces. The power invested in sardars by the Sandeman system created large bases of political support for elections and rebellions. These invasive central government actions were premised on false claims of Baloch political leaders mustering armies to overthrow the Pakistani government. The conflict cooled down after Gen. Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq seized power in his 1977 coup and freed the arrested Baloch leaders. While granting the insurgents general amnesty de-escalated the conflict over the next 20 years, Zia-ul-Haq failed to address the underlying issues.

The uprisings would also set a precedent for the involvement of other powers, particularly India, Iran, and Afghanistan. The historical region of Balochistan is currently split among three nations: Pakistan’s Balochistan province, eastern Iran, and southern Afghanistan. Tehran continues to face its own uprising in its Sistan and Baluchestan province, where Baloch groups support each other across the border. Afghanistan, already campaigning for Pakistan’s Pashtun areas, would become a sanctuary for Baloch resistance. As far back as the 1950s, Baloch leaders have sought refuge in Afghanistan. During the uprising in the 1970s, Afghanistan and India would play key roles in providing support and safe havens for Baloch armed groups. In addition, both countries would also gain Soviet and Iraqi support for various Baloch groups in Pakistan and Iran. As the conflict stagnated, Afghanistan and India would change their policy, partially due to their own changing domestic circumstances in the 1980s and 1990s.

In the 2000s, new Baloch armed groups were created in an attempt to liberate Balochistan, but they failed to gain traction until the 2005 rape of doctor Shazia Khalid by Pakistani military officers in the town of Sui. The government’s defense of the offenders was an inciting event for the ongoing conflict. Balochistan was militarized as a part of Gen. Pervez Musharraf’s “War on Terror” where he portrayed secular Baloch militants as under control of radical Islamists to justify his alienation and repression of nationalists. Perhaps the most significant event that galvanized Baloch separatism was the 2006 killing of veteran Baloch leader Akbar Khan Bugti during a military operation. The militarization, harassment campaigns, zero-tolerance policy, and kill-and-dump tactics enacted by Musharraf’s regime have been continued by successive governments in Pakistan. Thousands of Baloch activists and militants fled into U.S.-backed Afghanistan to escape Pakistani repression. Since 2007, several BLA commanders have been killed in Afghanistan. Afghanistan and its ally India would be accused of supporting the Baloch armed movement. Importantly, alongside accusations of foreign support to the Baloch insurgency, Islamabad promoted a narrative that “greedy sardars” were opposing development to maintain power.

To further stimulate Pakistan’s economy and take advantage of Balochistan’s resources and location, Pakistan turned to the Chinese for a panacea. The deal between Islamabad and Beijing to develop Gwadar into a deep-water sea-port and a fundamental part of the BRI is divisive and has highlighted the deep-seated inequality between Baloch people and Islamabad. Many Baloch argue that the mega-infrastructure projects are an example of contemporary colonialism and exploitation. Since 2003, Baloch separatists have focused their attacks on Chinese infrastructure, embassies, and nationals within Pakistan. Islamabad’s reliance on Chinese loans and investment has placed Pakistan in a position where it must ensure the success of CPEC, and Islamabad’s strategy of increased militarization to protect CPEC infrastructure has only served to galvanize Baloch militants in their opposition.

The Baloch insurgency has been complicated by the roles of neighboring countries. Baloch militants have used Iran and Afghanistan as safe havens to launch attacks across the border, which has increased tensions between Tehran and Islamabad despite occasional security cooperation. Afghanistan under the Taliban, while promising to crack down on armed groups, has largely been unable or unwilling to follow through. Indeed, the fall of the U.S.-backed government in Kabul allowed many Baloch armed groups to acquire armaments used by the former Afghan National Army. India, upon which exiled Baloch leaders have often called for help, has raised the issue of Balochistan in international forums, often in response to Pakistan’s own condemnations of India’s policies in Kashmir. Pakistan has accused India of supporting the Baloch insurgency, pointing to incidents such as the arrest of former Indian Navy officer Kulbhushan Jadhav on espionage charges. In 2016, Indian citizen Kulbushan Jadhav was arrested by Pakistan, which claims he was a RAW agent supporting Baloch agents. An Indian journalist’s investigation argued that Jadhav was a naval intelligence agent in Iran’s eastern province tracking pro-Pakistan militant groups. The incident highlights conflicting security goals for Balochistan within the region and points to possible cooperation between Indian and Iranian intelligence services.

The Dynamics of the Balochistan Armed Movement

Although the current insurgency’s roots can be traced from the early 2000s, it was only recently that violence has escalated. A 2020 analysis by the Armed Conflict Location & Event Database found a decline in conflict between 2015 and 2017, followed by a marked increase beginning in 2018. Among observers and analysts, the decline was attributed to Pakistan’s counterinsurgency efforts and weakness among the various Baloch organizations. The main Baloch separatist actors fractured into numerous splitter groups in the 2010s that undermined the separatist movement.

A big part of the decline followed Pakistan’s toughening stance against insurgent violence following the 2014 Peshawar school massacre by the militant group Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan. Pakistan responded by adopting the National Action Plan in 2015 to strengthen its fight against terrorism. Within the 20-point plan was a call for empowering stakeholders in Balochistan to allow for political reconciliation. However, the actual progress on this point was mixed at best. Instead, the continued reliance on military force and repression led to a resurgence of violence.

A look at the Baloch separatists today shows a very different insurgency than what was seen since 1948. First, there has been a general consolidation of Baloch armed groups, especially with the 2018 formation of the BRAS alliance, which consists of the BLA, the Balochistan Liberation Front, the Baloch Republican Guard, the Baloch Republican Army (BRA) – and, as of 2020, the Sindhudesh Revolutionary Army, which is fighting for independence in Sindh province. These groups share a common goal of fighting what they view as a Punjabi-dominated Pakistani state, as well as concerns on how the provinces of Sindh and Balochistan are being used to further the CPEC project. They also share targets, including Pakistani security forces, Chinese infrastructure and civilians, and attacks against “Punjabi settlers.”

The alliance facilitates the coordination of rebel actions. Second, the insurgency has radicalized from Pakistan’s repression of the Baloch people and the continued forced exiling of many moderate voices. As exiled Baloch journalist Kiyya Baloch argued, Islamabad’s policy of targeting Baloch individuals has only furthered fuel unrest, especially as it has strengthened the narrative of separatist groups. Third, the makeup of the individual fighters and supporters joining the armed groups has broadened. Part of this change has come from the infighting between tribal leaders abroad and their local ground commanders.

In the past, rebellion against the Pakistani state was linked to various tribal communities and their sardars. This was especially true in the early years of the insurgency following the 2006 Bugti assassination. In an interview with the authors, Bahot Baloch, a freelance journalist from Balochistan, highlights the shifting conditions on the ground as the role of sardars, especially in asylum overseas, has been reduced: “some sardars and their sons led major Baloch resistance groups in the past, but in the last five years these individuals have almost completely lost their influence over the resistance groups.”

The sardars of major tribes are split between pro-government and separatist factions: Hyrbyair Marri is associated with separatism, while his older brother Changez Marri has held high positions in the Balochistan provincial government. While the Marri tribe is aligned with the BLA, internal conflicts between the Gazzini Marri and Bijjarani Marri have led to violence. Even then, a majority of sardars have sided with the government, and the character of Baloch resistance is shifting. Neither of the current leaders of the BLA and the Balochistan Liberation front (BLF), Bashir Zeb and Dr. Allah Nizar Baloch, are sardars, and the role of sardars in the current movement may be overstated. Although some groups are still predominantly identified with certain tribes, many rebel groups have been increasingly pulling from Balochistan’s middle class. This provides the insurgency with an increasingly educated and wealthier base for support.

As the insurgents have begun to broaden their base, this has also led to the sidelining of prominent Baloch sardars and their families, such as the Marris and Bugtis, who have claimed asylum in Europe. Instead, it seems that the unifying Baloch armed movement has been accompanied by local Baloch leaders taking over the armed groups.

For instance, the United Baloch Army (UBA) was formed in 2010 as a splinter from the BLA due to a dispute between the brothers Hyrbyair and Mehran Marri. This led to Mehran creating the UBA, although the faction would continue to face its own splits. There was an attempt by Mehran to sideline a popular local leader, spokesman Mureed Baloch (real name Sarfraz Bangulzai), but this has done little to stem Mureed’s popularity or influence. This was especially relevant as Mehran resides in Europe, while Mureed is thought to be in Balochistan. The BRA, formed after the killing of Nawab Akbar Bugti in 2006, was reportedly led by Nawab’s grandson, Brahumdagh Bugti, though he denied any role in militancy. However, an internal schism in 2018 split the BRA into two factions: those loyal to Bugti, represented by BRA spokesman Sarbarz Baloch, and those loyal to a regional commander known as Gulzar Imam. Most BRA fighters aligned themselves with Imam, who would go on to win the favor of other BRA commanders. Imam’s BRA faction aligned with the BRAS alliance. Despite BRA’s early association with the Bugti tribe, Imam has been critical of the Baloch tribes, arguing that it has weakened the Balch movement in the past.

Nor is this pushback against traditional tribal figures limited to the smaller armed groups. For instance in 2018, the BLA put out a statement claiming it has no representatives in London, saying the group “completely disassociates itself from a particular ‘egoistic person and his tiny group’ from today,” a thinly veiled reference to Hyrbyair Marri. Despite this, there is a faction within the BLA that maintains its own spokesman and ties to the tribal leadership, although it seems to be the weaker of the two factions. This is a pattern seen in multiple Baloch armed groups. This is not to say that the sardars or exiled leaders no longer play a role in the insurgency, but their influence has diminished. Especially among activists that identify themselves as part of the nationalist movement, the sardars and tribal leaders also play a part in exploiting Balochistan and their people. As Lateef Johar Baloch, deputy coordinator of the Human Rights Council of Balochistan, said in an interview with the authors, “[the] Sardari system is based on exploiting the Baloch people, and Pakistan’s policies and interests are to exploit Balochistan’s natural resources and geopolitics importance, which is why using the sardars is a must for the state.”

The Baloch Armed Movement Today

The consolidation of armed groups continues today, with the BRA and UBA merging together under the BRAS alliance as the Balochistan National Army. Notably, the consolidation probably was able to happen because of the marginalization of tribal figures. Indeed, it was Mureed Baloch’s branch of the UBA that would formally merge with BRAS rather than any remnants of the Marri’s fighters. Shortly after the reported capture of Balochistan National Army leader Gulzar Imam, the Marri-aligned branch of the UBA issued a statement on Telegram that they had never merged with any other group, instead portraying it as former UBA members who chose to join the organization.

A major figure responsible for the current stage of the Baloch insurgency and the push for consolidation is Aslam Baloch, a founding BLA member who became its leader in 2017. Aslam founded the BLA’s Majeed Brigade, an elite unit that carries out fedayeen/suicide style attacks. The Majeed Brigade carried out its first attack in 2011, but would not conduct another operation until 2017 when Aslam assumed leadership. Importantly, it was due to Aslam’s initiative with Allah Nizar Baloch that BRAS was formed, unifying the major Baloch separatist groups. Despite his assassination on Dec. 25, 2018, Aslam’s influence continues to be prevalent in the ongoing Baloch insurgency.

Unlike many of the other armed organizations operating in Balochistan today, all the BRAS groups remain secular in outlook and emphasize liberation for Balochistan and Sindh. According to Baloch activist Lateef Johar Baloch, many Baloch groups were previously inspired by Marxism and Marxist figures like Che Guevara, but emphasis remains on national liberation and secularism – a stark contrast to the Islamic identity foundational for Pakistan’s nationhood. Many Baloch activists and outside scholars have argued that Pakistan’s response to Baloch nationalism has been to Islamicize the region and use extremist actors to attack Baloch armed groups, which has exacerbated the spread of sectarianism and violent Islamists in Balochistan. This has led to a string of particularly deadly sectarian attacks, such as those targeting the Shia Hazara community in Quetta.

Recommendations

The nationalist insurgency in Balochistan is evolving from fractious groups toward a united front. The consolidation has been correlated with a shift away from tribal leadership and an expanding base of general support and fighters within the Baloch rebellion.

Pakistan has primarily resolved to solve the conflict through repression against both activists in Balochistan and dissidents abroad. Following the 2020 drownings of Baloch refugees, European intelligence agencies warned Pakistani dissidents, including Baloch exiles, that they were targets for assassinations by Pakistan’s intelligence agency. This is in addition to the regular repression that many Baloch activists face in Pakistan, especially those who have to deal with pro-government militias and state-backed death squads. All this is worsened by the fact that Pakistani media has largely avoided reporting on conditions in Balochistan.

The United States and the international community should take steps to stabilize Pakistan and encourage the government to follow through on calls for reconciliation and political reforms between Islamabad and Balochistan. Since 2005, Baloch militant groups have issued demands for Islamabad to halt the construction of military bases and to protect the Baloch people. Senior elected officials in Balochistan have made serious attempts to establish peace talks in the past. Baloch separatist leaders offered to negotiate on the condition that military operations ended and personnel withdraw, but the military refused the offer. De-escalating state violence in Balochistan and scaling back the military presence is a confidence-building measure that could renew peace talks.

Islamabad’s hope that simply bringing Chinese money and projects to develop Balochistan will end the insurgency is severely misguided. The historic lack of investment in Balochistan province has created interlocking humanitarian, education, food, and water crises. CPEC and similar projects are seen as extractive and have only amplified Baloch anxiety over the unequal distribution of their resources and loss of land. Civilian protest movements like Give Rights to Gwadar have issued demands that address these crises, including providing accessible utilities and clean drinking water, recognizing Baloch economic autonomy such as control of fishing rights, demilitarizing the province by removing checkpoints, and investing in provincial education by establishing a university. Climate change and worsening natural disasters like the recent flooding only exacerbate the existing situation.

The conflict has heightened security concerns with neighboring states in an already unstable region. Beijing’s willingness to overlook human rights abuses in BRI partner countries actively contributes to the militarization of Balochistan. International partners can diversify Pakistan’s economic security with alternative development projects that include Baloch people as stakeholders in their political and economic sovereignty. Regardless of one’s views toward the position of Balochistan, Pakistan’s counter-insurgency tactics have only led to escalating violence and strengthened the separatist narrative. The dynamic Islamabad has created marginalizes and excludes more Baloch people, further radicalizing the separatist movement. Islamabad’s policies in Balochistan actively inflame the insurgency and are contributing to the insecurity of the region.

Wil Sahar Patrick is a doctoral candidate in the Critical Geographies Research Lab at the University of Victoria. He is a political geographer researching the intersections of infrastructure, political networks, and local self-governance in Central Asia and monument and infrastructure controversies in North America. He tweets at @wilpoligeo.

Hari Prasad is a research associate with Critica Research and Analysis, where he focuses on Middle Eastern and South Asian Politics and Security, particularly armed actors and religious movements. He tweets at @hariprasad91.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of the New Lines Institute.