Preventing Another al Qaeda-Affiliated Quasi-State: Countering JNIM’s Strategic Civilian Engagement in the Sahel

An al Qaeda affiliate is on track to gain firm control over swaths of territory in the central Sahel. The group, Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM), encapsulates al Qaeda as the world saw it in Iraq and Syria as it stones and maims citizens in West Africa, making examples of those who do not abide by the group’s perverse version of shariah law. Without intervention, JNIM will further establish itself as a non-traditional governing entity in Burkina Faso and Mali while continuing its operations and attacks in Niger and into the littoral states. This cementing of the group would undoubtedly increase the threat of JNIM expanding its territorial control into coastal West Africa. Moreover, the group’s visibility and ties to veteran al Qaeda leaders could embolden global transnational terrorist networks and enhance threats, including the risk of ideologically motivated lone wolf attacks in Europe and the United States. Terrorism studies and counterterrorism policies must adapt to prevent more al Qaeda affiliates or affiliated groups from taking root as permanent quasi-state governing bodies, as al Shabaab and Hay’at Tahrir al-Shaam have in Somalia and Syria. Counterterrorism in West Africa has not been successful, partially because counterterrorism operations are not countering all the terrorist groups’ operations and strategies – especially not the non-kinetic operations and strategies.

Counterterrorism and Risk Aversion

The United States spent trillions on the Global War on Terrorism and lost almost 7,000 service members. Washington and the American people’s awareness of these costs has influenced U.S counterterrorism strategy and tactics since – the propagation of targeted drone strikes (posing low to no risk to American forces), the hurried and infamous withdrawal from Afghanistan, and a drawdown of Operation Inherent Resolve. While the costs of the war on terrorism have been cause for care and risk analysis, not all counterterrorism policies and priorities have been off ramped into conflict prevention and stabilization purposes. Rather, counterterrorism is continuously de-prioritized in favor of current events, like the situation in Gaza, and for focus on the U.S. geopolitical competition with Russia and China. This risk aversion is understandable, but there are more ways to counter terrorist groups past targeted drone strikes, policing the cyber space, and counter-terrorist financing. Inter-agency coordination and comprehensive counterterrorism can even be implemented in a way that also address great power competition and support democratic institutions, values, and human rights.

The Turn Away From Terrorism

This step away from counterterrorism as a point of policy (even its use as a term having fallen out of favor) is dangerous, especially in areas like the Sahel where a clear terrorism threat exists. The world is beginning to see the possible effects of the turn away from counterterrorism following the large-scale attack on a Moscow concert hall March 22 by the Islamic State’s Khorasan Province. It is imperative that the U.S. call the threat of terrorism – and the field of counterterrorism – what it is in order to be prepared and properly resourced to disrupt its resurgence, whether sparked by attacks like the one in Moscow or by the growing al Qaeda affiliate in the Sahel.

Preventing and Countering Terrorism in West Africa

There is a clear connection between preventing and countering terrorism in West Africa. JNIM’s civilian engagement strategy presented in this publication connects the tactical, operational, and strategic operations/levels of this al Qaeda-affiliate. These operational and strategic connections prove not only the benefit and relevance of a coordinated and comprehensive counterterrorism strategy but prove its necessity. A comprehensive security and stabilization approach is needed to counter and mitigate the spread of terrorist groups’ territorial hold and influence in the Sahel because JNIM is uniquely operating at the intersection.

The countering of JNIM’s civilian engagement strategy involves both development and security, in that while JNIM is a terrorist group, the strategy identified here is engagement with civilians that does not resemble the terrorist insurgencies the world is used to – characterized by terror and bloody terrorist attacks. Rather, in addition to these “traditional” terrorist insurgency strategies, JNIM also pursues a non-traditional terrorist strategy that is non-kinetic. Countering JNIM’s non-kinetic engagement in its deployment will look more like civilian affairs and strengthening a positive presence of district and national government in geographic areas where JNIM is non-kinetically engaging or may engage next.

The USAID Office of Transition Initiatives leads excellent localized programming with local civil society in the Sahel connected to the Global Fragility Act. Engagement with the coastal West African countries is a priority for this policy, which aims to prevent the spread of conflict, violence, and terrorism by supporting and strengthening local institutions and communities. However, without connecting this conflict prevention work with the countering of the security threat itself, the Global Fragility Act will not succeed to its full potential and could even fail. Any U.S. contribution to conflict prevention – no matter the degree of U.S. involvement – must be coordinated with security and military assistance to form a comprehensive prevention and counterterrorism strategy, especially when the prevention and stabilization is directly linked to the terrorist threat.

An important – but under-addressed – area of terrorism studies and counterterrorism policies involves implementing policies and programs that consider and/or prevent civilian engagement with terrorist groups and circumvent the groups’ methods of controlling populations. Al Qaeda affiliates in particular employ strategies and means of engagement to exercise control over people in a given territory, as Hay’at Tahrir al-Shaam has done in northwestern Syria, and as JNIM is currently doing in the Sahel. These include largely non-kinetic and low-kinetic operations that lead to territorial control and ultimately non-traditional governance, or the creation of a quasi-state. Existing security and military assistance and development support must work in concert with and in consideration of these strategies as they endanger democratic gains for the continent and add to the global terrorism threat – including threats to U.S. interests and national security.

JNIM successes in West Africa are likely to embolden al Qaeda – and possibly ISIS – and could instigate a global resurgence of these transnational terrorist networks. In fact, the Long War Journal recently reported that al Qaeda opened eight new training camps and madrasas (schools) in Afghanistan. While U.S. drone strike campaigns targeting transnational terrorist group leaders have been largely successful in taking out key commanders and strategists, the command level of these groups has not been eliminated. A resurgence of al Qaeda and ISIS networks could be particularly potent considering the current global climate of polarization that has fostered violent movements. Such circumstances would increase the risk of ideologically motivated lone wolf attacks in the West – especially heightening the terrorist threat levels in Europe.

Framing the al Qaeda and ISIS Affiliates in the Sahel

JNIM is the most active of the two al Qaeda and ISIS affiliates in the Sahel, where 47% of all deaths by terrorist attack occur. JNIM’s engagement with civilians supports its territorial expansion in West Africa. Author analysis of ACLED data from Jan. 1, 2022, to Jan. 1, 2024, identified distinct operational strategies in JNIM’s activity against civilians that are surprisingly non-lethal and low-lethal, considering the activity and insurgency capabilities of the group.

In 2022 and 2023, ACLED reported just over 7,000 events perpetrated by the four al Qaeda and ISIS affiliates in West Africa: JNIM, Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP), and Boko Haram (which has an enclave operating in Niger, but operates predominantly in Nigeria and the Lake Chad basin). These events took place in the countries that make up the Sahel terrorist hot zone and states in the periphery: Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Benin, Togo, and Ghana, and Mauritania. The coastal West African states – especially Ghana, Benin, and Togo – are also seeing activity by these groups and are sincerely concerned about stopping them from further spreading into their territories. Mauritania is among the peripheral countries but has not experienced activity from these groups; experts surmise that willingness to negotiate and engage with jihadists is part of the reason why, while others point to the country being an Islamic republic with a mixed sharia and secular judicial system.

Of all the activity ACLED attributed to the al Qaeda and ISIS affiliates in the subregion, 2,609 events were considered actions against civilians. This figure omits those carried out by civilians; JNIM-ISGS clashes; and conflict between JNIM and the state, police, gendarme, fighters from the Volunteers for the Defense of the Homeland (VDP), or Wagner Group or other foreign security forces which may be classified as counterterrorism or counterinsurgency operations.

In 2005, Ayman al-Zawahiri, second emir of al Qaeda, sent a letter to Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, founder and emir of al Qaeda in Iraq (which would become ISIS in 2013) outlining and explaining the reasoning for al Qaeda’s operating strategies. Al Qaeda affiliates are more cognizant than ISIS affiliates of the impact that degrees of violence and targeting of other Muslims have on their desired support base and the population they wish to govern under their version of shariah law. Attacking and indiscriminately killing any Muslim, for example, causes great backlash with any Muslim population al Qaeda may rely on for support or seek to control under what they refer to as traditional shariah governance (though it is not). The operations of groups that have pledged loyalty to al Qaeda are greatly influenced by this al Qaeda-specific operationalization of strategic goals and the connected ideology.

JNIM’s civilian engagements have followed suit – largely due to its AQIM origins. AQIM is an older al Qaeda-affiliate whose veteran al Qaeda Central-era leadership influenced JNIM; for example, guidance from al Qaeda leadership directed JNIM to refrain from conducting extreme attacks against civilians in Mali. JNIM has gone a step further to operationalize its civilian engagements, connecting them to its territorial expansion strategy. By contrast, the modus operandi of ISIS affiliates in the Sahel includes the indiscriminate attacking and killing of civilians.

Strong-Arming Civilians

JNIM’s intentionally low-lethal and non-lethal civilian engagement strategy ultimately looks like a squeeze on freedom of movement with roadblocks and extortion, intimidation, and attacks at road checkpoints. JNIM does kill and attack civilians, including beheading some accused of sharing information with security forces or ISGS or of not abiding by its version of Shariah law. It then puts those heads on public display to threaten the townsfolk to comply. However, JNIM has been seen to purposefully avoid killing civilians en masse – with the intent of not alienating the populations it intends to overtake, control, and profit from.

While the al Qaeda affiliate’s engagements with civilians are careful, they are frequently brutal; civilians might choose to cooperate, but that choice is made under threat of violence. JNIM kills its rivals’ supporters and informants, whether security forces or ISGS. In towns controlled by JNIM, the punishment for reported stealing is a maiming carried out in the town square, and those deemed sexually promiscuous are stoned to death in the same public fashion. The civilian experience must be prioritized and the second objective of the Global Fragility Act 10-Year Plan in Coastal West Africa as well as related military civilian-affairs mandates amended accordingly.

Currently, the Global Fragility Act and reports on terrorism, such as the 2023 UNDP report “Journey to Extremism in Africa: Pathways to Recruitment and Disengagement” portray civilian engagement with terrorism and terrorist groups in the Sahel in two ways: radicalization by way of grievances against the state, and pathway to engagement due to lack of socio-economic opportunity or marginalization. Neither consider a coerced civilian population’s decision to engage and comply with terrorist groups because that compliance is more likely to ensure their livelihood and survival than sharing information on terrorist groups to state or foreign forces would. This decision to comply or run (which is also seen within ACLED’s event notes), add a layer of understanding to why prevention and counterterrorism efforts have not worked thus far. Add in reports of indiscriminate attacks as a part of counterterrorism operations (by Wagner, the state, even French and coalition air strikes) and there is a strong argument that a trusted positive presence is terrorism prevention. ACLED notes of “attacks against civilians” include reports of townsfolk willingly joining in to bludgeon a couple to death for their purported sexual promiscuity.

In addition to direct violence, JNIM also controls access to basic services, capital, and transport in areas under its aegis, allowing it to exert pressure on the fundamental aspects of everyday life that can lead to the slow demise of livelihood felt by all civilians there. This explains JNIM’s success in expanding its control. The ACLED dataset includes accounts – many from local sources kept anonymous for safety reasons – of incidents showing clear disruption of and control over civilian movement and access to food, water, cellular communications, electricity, and the like. Maintaining a livelihood in parts of West Africa is a constant cycle of growing or creating goods and services and livestock and then transporting them to market for sale or trade. In areas without freedom of movement (say, to the next town where one may usually travel to market) or access to some kind of livelihood, merely existing becomes difficult, and cooperation to some degree is necessary to stay alive.

This civilian engagement strategy has resulted in great dividends for JNIM – such as territorial expansion in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger – since its founding in 2017, and recently into the littoral states. If U.S. support in the region does not coalesce to address this civilian engagement strategy, then JNIM will likely take root like al Shabaab in Somalia, as well as succeed in its advancement into coastal West Africa. Considering those littoral states are developing democracies, this will drastically undercut democratic gains in Africa as well as contribute to the likelihood of a global Salafist-jihadist resurgence.

Abduction and Release

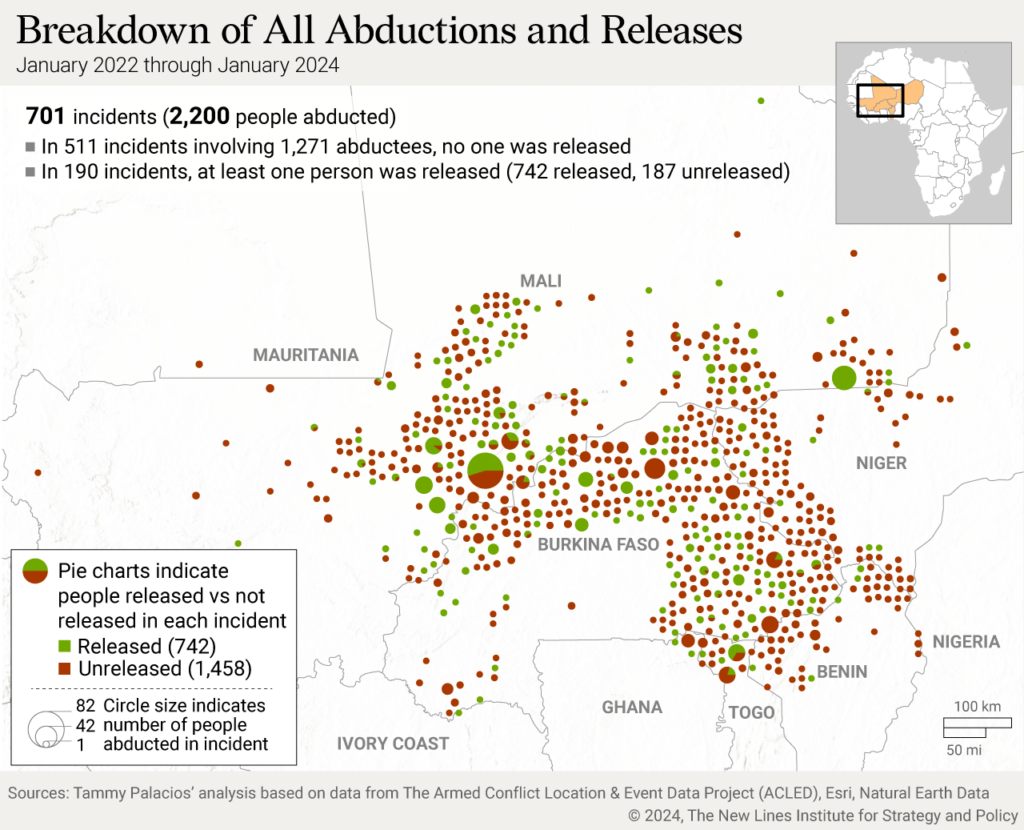

Central to JNIM’s successful territorial gains and control is the group’s abduction and release strategy, identified by the author’s analysis of ACLED data and tracking of the local operations of al Qaeda affiliates and al Qaeda more broadly. This is a rules-based strategy for engagement with civilians – comply or die – giving them clear direction and ample opportunity to follow the rules and live, resulting in fewer lethal interactions with JNIM. Civilians are keen to follow these rules, particularly since this tactic is used after JNIM establishes control over transport, and services, leaving the civilian population the stark choice between trying to live without the means to survive or cooperating to the degree that JNIM demands. As JNIM’s control tightens, the group implements its version of Shariah law. Civilians can try to flee, though there are reports of those attempts being stopped. The author identified this trend after re-collating ACLED’s event data on al Qaeda and ISIS activity in West Africa from Jan. 1, 2022, through Jan. 1, 2024. Of all the al Qaeda and ISIS affiliates in West Africa, JNIM uniquely dominates in low-kinetic and non-kinetic civilian engagement.

Kidnapping in a criminal capacity is common across West Africa and is perpetrated by ISWAP and Boko Haram (especially the latter), as well as by bandits and other criminals. These groups typically target minors in the pursuit of profit (kidnappers demand and often collect ransom) and recruitment (boys and men are conscripted, and girls and women are forcibly married off to group members and sexually assaulted). While JNIM also kidnaps for ransom, its strategy differs from those used by other armed nonstate actors in the region. Abductions perpetrated by JNIM serve the purpose of territorial expansion and control. Previously, when JNIM would go into a town and make its demands or intentions known, it would begin abducting locals if the population did not comply. This is made clear in Mathieu Bere’s dissertation “Jihadist insurgency, Civilians’ Targeting, and Conflict Dynamics in the Sahel: A Case Study of Burkina Faso.” Building off Bere’s work on al Qaeda and ISIS in the Sahel on data since 2022 this civilian targeting now clearly resembles a terrorist strategy.

According to author analysis of ACLED’s data and event notes, abductees are most often key individuals – persons with influence and/or access (such as mayors, chiefs and traditional leaders, local and international NGO workers, imams, and pastors), or persons related, married, or who work with them, and affiliated with areas of interest to the group (such as schools and religious institutions as they relate to implementing the group’s version of shariah law). Author tracking of notes in the ACLED database stating when kidnapped individuals were released (if they were noted as having been released after their abduction; not all outcomes of kidnappings were recorded) led to the conclusion that in this time frame NGO personnel in general were released most quickly (often after being held for a day or less) while other individuals were held for months. Quick release may involve ransom payments, and it is likely that NGOs – especially international ones – have prepared for such a situation. However, the event notes recorded by ACLED rarely include information about whether a ransom was paid.

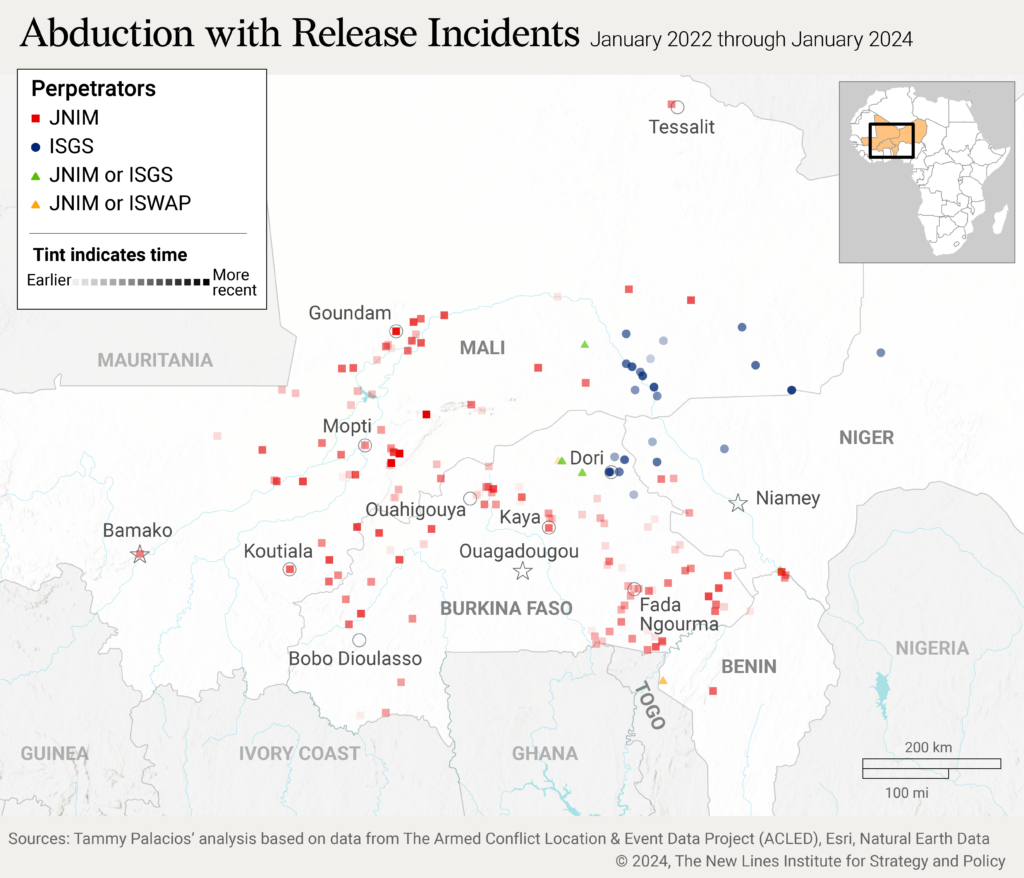

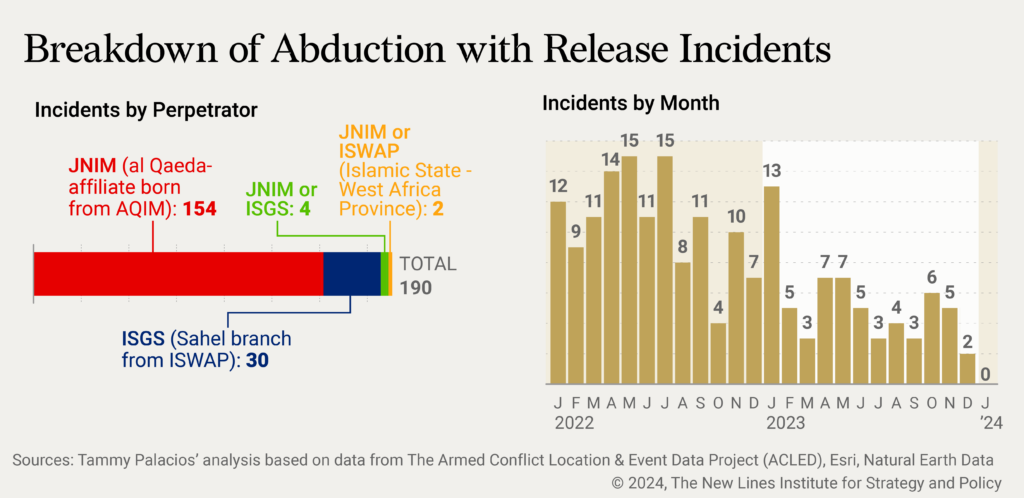

According to the author’s analysis of ACLED data, while many nonstate armed actors kidnap civilians, abduction and release is unique to JNIM (see the graphic below). JNIM was responsible for up to 84% of all such incidents reported by ACLED as having occurred between Jan. 1, 2022, and Jan. 1, 2024.

Total Effect on Civilians

Fatalities caused by terrorist events do not represent the total effect that terrorist groups have on the civilian population. Maps depicting terrorist activity do not indicate the number of civilians injured, attacked, threatened, or controlled by militant groups. For example, author analysis of ACLED data on al Qaeda and ISIS affiliates in select West African countries between Jan. 1, 2022, and Jan. 1, 2024, tagged and identified trends in who was targeted as well as when, where, and possibly why. One conclusion of this analysis is that most JNIM engagement with or attacks on civilians most often occur in two areas: roads and markets.

JNIM conducts checkpoints on roads within its general area of control and connected to its expansion efforts. Hundreds of civilians may be controlled and feel threatened at any given checkpoint by JNIM fighters who stop passenger vehicles, commercial trucks, pickups transporting goods and livestock, and transport buses. The fighters check IDs and cell phones; extort or steal belongings, cash, phones, and gold; and seize vehicles (including ambulances) and persons themselves. The abductions conducted at these checkpoints often target NGO personnel, interrupting their movement. And while they are often quickly released, other abductees may never be. While many of these interactions may be nonlethal, JNIM also intimidates civilians passing on foot and by car or bus by shooting indiscriminately. At times, the gunfire kills both commercial and passenger drivers and/or passengers; and while this study is on civilian engagement – if a government soldier or VDP gets swept up at a checkpoint, their fate is often death once they are identified as such. All of this creates trauma in a population that is often mobile and relies on freedom of movement for its livelihood. M.P. Trân outlines the importance of better focusing on and understanding road networks, as well as outlines how road network protection can be enhanced in his 2023 dissertation “Protective Resource Allocation on Critical Road Segments: The Case of Mali and the Fight against Terrorism.” While “road network protection” may not sound like counterterrorism, this is a core non-kinetic example of how civilians can be protected, and al Qaeda and ISIS countered or their spread mitigated.

JNIM also targets civilians at markets – gathering spots where people commonly go to sell and procure goods, services, and livestock. This interaction between JNIM and civilians at market has two aspects: Markets not only offer an opportunity-rich environment, given the large numbers of civilians congregating there, but also JNIM can profit there by selling livestock it has stolen elsewhere, according to event notes recorded by ACLED on al Qaeda and ISIS affiliate activity in West Africa from Jan. 1, 2022, to Jan. 1, 2024.

Countering Terrorist Territorial Expansion

Beyond affecting the civilian population and governance in areas under terrorist groups’ control, the expansion of the territory these groups hold also affects any state building, NGO and civil society capacity building, development, and security assistance from regional and international actors. The Global Fragility Act and the requisite 10-year conflict prevention strategies for coastal West Africa are especially impacted by, and in fact were formed and passed due to, the impending threat of al Qaeda and ISIS expansion in the Sahel subregion.

The U.S. provides hundreds of millions of dollars in development aid to West Africa, often through local actors such as civil society organizations, and for two decades it has participated in joint military exercises and provided security support with equipment, training, and advisers. The U.S. efforts are supported by myriad allied European-funded development projects and compete with Chinese and Russian assistance across the continent and in the region. The presence of Russia’s Africa Corps (formerly the Russian paramilitary organization Wagner Group) connects these counterterrorism efforts to the great power competition with Russia.

However, there are hindrances to more U.S. involvement in the region. Military coups in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger – as well as France’s withdrawal, which ended the decade-long counterterrorism Operation Barkhane – complicate U.S. involvement in the region. Section 7008 places limitation on foreign aid to countries whose governments came to power in a military coup; the U.S. military also has statutes for engagement in these contexts.

However, the U.S. is operating in West Africa – just not coordinating efforts to the level necessary for maximum effectiveness of monies, partnerships, and programming. The U.S. National Guard have long partnerships and participate in joint training operations in West Africa, Nigeria continues to be a mainstay U.S. partner in Africa, and in 2023 the Bureau of Humanitarian Assistance at USAID contributed $658 million in aid to West Africa. There is ample opportunity for the existing efforts to be more effective. But USAID, DOD, and U.S. security and development entities require adequate resources and higher-situated processes for their mandates to support the coordination and quick decision making and implementation necessary to improving their efficacy.

Policy Recommendations

It has been long acknowledged that terrorist groups – and especially al Qaeda-affiliated groups – adapt, especially to escape counterterrorism targeting. Greater coordination and communication are long overdue when it comes to preventing and countering terrorism and terrorists’ efforts. Preventing and countering violent extremism (P/CVE), violent extremist organizations (VEOs), and counterterrorism (CT) and terrorist groups are currently tangentially connected but represented by different mandates and policies. There is great overlap, especially when considering the same geographic area, and at times the only difference between P/CVE and CT is politics (comfortability to a term) and proximity to violent action or terrorist attack and operations. It is imperative that terrorism prevention and preventing and countering violent extremism efforts are coordinated and considered as one, especially since JNIM has proven that terrorist groups have non-kinetic and civilian-focused operations and strategies.

JNIM’s approach means that the U.S. must rewind its counterterrorism approach to include non-kinetic engagement – this can be accomplished by coalescing P/CVE and terrorism prevention/CT information and strategies. JNIM, which is lethal and conducts terrorist attacks, is endangering civilians in a way that is not currently addressed or being countered in U.S. engagement or strategy. Care is needed so as not to over-securitize development, but this care cannot preclude communication and coordination to address all aspects of civilian security – no matter the security actor or terminology.

If civilian security were endangered by indiscriminate state attacks, human rights and advocacy groups would see clear alignment with their mandates to protect human rights and good governance and safety – while civilian rights, movement, and safety being restricted by a terrorist group does not clearly align. Offices at this intersection and operating in locales where non-kinetic civilian engagement is an aspect of a terrorist groups’ operations should consider these historical alignments or non-alignments. Prevention, including efforts to strengthen civil society and youth and women involvement and opportunity on the development side, and civilian affairs efforts on the security side – must all be examined in the parts they play to the shared objectives of civilian peace and security in a specific geographic location.

Whole-of-Government Approach in West Africa

U.S. policies that promote bottom-up development and social cohesion have grown exponentially since the Global War on Terrorism, but without the needed level of collaboration between the development and security sectors of the U.S. government and military to successfully mitigate conflicts and stifle the growth of terrorist groups.

- Congress should support the U.S. policymakers working to implement the Global Fragility Act and the connected 10-year prevention strategies in coastal West Africa, so resources (including personnel) are available to properly implement the whole-of-government strategy that both the State and Defense (DOD) departments have agreed is necessary. That approach mitigates “fragmentation, overlap and duplication” and can be accomplished with “joint strategies” wherein all relevant departments and centers within the Departments of State, Defense and Justice coalesce for a comprehensive Sahel strategy in which all efforts can compound for maximum effect.

- West African civil society should be involved in finalizing the 10-Year Strategic Plan for Coastal West Africa – possible through active involvement of the DC GFA Coalition, a non-partisan coalition of more than 100 peacebuilding, humanitarian, development, faith-based organizations who also engage civil society. The New Lines Institute is also working to connect more civil society organizations in West Africa to this effort with policy roundtables as the Priority Sustainable Counterterrorism program outlines that supporting civil society organizations, especially smaller and more rurally located ones in the northern regions of periphery states is a clear sustainable solution that, if prioritized, supports shared U.S. and African-partner localization, stabilization, and prevention policy priorities. Prioritization and proper sourcing of this strategy would be in lieu of additional U.S. boots on the ground, offering an alternative to a situation that creates great hesitancy for domestic and international politics reasons.

- Civil affairs and military assistance components of the DOD are key to the implementation of a whole-of-government approach, particularly to the U.S.’s partnership to support peace and security in West Africa. Cross-sector efforts should especially prioritize the streamlining of processes to speed implementation and decision making. Shared State/DOD resource and funding buckets could support timely and efficient implementation of U.S. development and security engagement both meant to prevent and mitigate the spread of conflict and terrorism. The intersection of development and security across the U.S. government and military apparatus is also plagued by differences in terminology (peacebuilding vs. conflict prevention vs. counterterrorism vs. irregular warfare vs. good governance vs. security assistance), which complicates implementation. Focused policy from de-bureaucratized systems would be more efficient and effective.

- The United Nations, African states, the United States, and Europe agree upon the need for a whole-of-government approach to prevent and counter terrorism. Yet, outside of the Offices that make up the inter-agency Global Fragility Act Secretariat, engagement and coordination between development and security agencies moves slower and can be plagued by bureaucracy. This hesitation to engage at the intersection of development and security can be explained by lack of clarity for all offices in terms of the connection to their mandates, and due to each office’s hesitation to lead efforts or spend their funds. Two things are needed to support streamlined implementation of these approaches: Shared buckets of funding for logistical support in a specific locale – for example, the terrorist hot zone and periphery in West Africa. Moreover, high-level authorities and collaboration to integrate strategies so that existing efforts may complement each other at least in timeline and geography, to more efficiently harness limited resources and policy focus for effective change.

Improving Coordination of Efforts

JNIM follows a civilian engagement strategy that directly supports the terrorist groups’ territorial expansion and control. Counterinsurgency, targeted drone strikes, and ambushes do not counter or even address this aspect of the terrorist groups’ operations and strategy. This non-kinetic aspect of JNIM’s modus operandi does not fit the definition of a terrorist act, though it does restrict access and movement and is linked to a threat to livelihood and life. Development support, especially with civil society and district-level and local authorities (who represent and often engage with the civilian population) must be much more coordinated and intentional in strengthening positive state presence to counter this threat. This positive presence counters terrorist civilian engagement and thus counters territorial expansion and population control by al Qaeda and ISIS.

The U.S. must call terrorism what it is, in order to be prepared and properly resourced. This identification must occur at Congress and within U.S. entities – but this recognition should remain within U.S. policy and within the inter-agency and should be carefully labeled in diplomatic engagement and deployment of civilian affairs and development work in a counterterrorism locale.

This need for prevention and counterterrorism coordination, admonition of terrorism, and counterterrorism and requisite resourcing within the U.S. inter-agency will be especially obvious in the adaptation of a structure to allow for a whole-of-government approach both within U.S. government and in coordinating international engagement.

Next Steps

At the head table of much of these recommendations for change sits Congress, especially as related to acknowledging and respecting counterterrorism as a policy priority, and in structural and resource support of the Global Fragility Act. Congress should focus on supporting the U.S. policymakers working to implement the Global Fragility Act and the connected 10-year prevention strategies in coastal West Africa, rather than waiting on deliverables and tangible results or positive indicators only two years into a 10-year plan.

If U.S. support in the region does not coalesce to address this civilian engagement strategy, then JNIM will likely take root like al Shabaab in Somalia. If JNIM advances into the developing democracies along the West African coast, its actions will drastically undercut democratic gains in Africa and boost the likelihood of a global Salafist-jihadist resurgence. Perceived success by any al Qaeda or ISIS affiliate, especially lasting success as JNIM and ISGS have exhibited in the Sahel, threatens to greatly bolster the confidence in al Qaeda and ISIS as global networks or violent extremism/terrorism as transnational phenomenon – greatly supporting the likelihood of transnational terrorist attacks and transnational terrorism-inspired lone wolf acts.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of the New Lines Institute.