On July 6, 2020, Dr. Husham al-Hashimi was killed in his home country of Iraq. He had submitted a series of insightful articles to the Newlines Institute before his death, and we will publish those articles throughout the summer.

Editor’s Note: This Net Assessment is part 13 of “ISIS 2020” – a series of briefings about the current status of the Islamic State by authors from different parts of the region. It is published by the Newlines Institute‘s Nonstate Actors program. Parts one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine, ten, eleven, and twelve were released weekly since April 28.

After the collapse of the Islamic State’s physical caliphate in 2017 in Iraq and last year in Syria, the return of ISIS fighters’ families to their homes has been discussed almost exclusively in the context of Western countries. Most of these nations have been reluctant to allow these families to return to their home countries, mainly for security and political reasons and because of the difficulty of prosecuting anyone involved with ISIS in Syria. But the issue is just as (if not more) complex in places like Iraq and Syria, where many people still reject the return of those they labelled as “ISIS families” – families or clans with members (now active, imprisoned, or deceased) who joined the organization after 2014. Throughout much of Iraq, residents and authorities consider these families potential enablers of renewed ISIS activities. Despite local officials’ and entities’ intensive efforts to reintegrate these families with their communities, security concerns, tribal and sectarian issues, and other formidable obstacles remain.

Attacks Linked to Returning Families

“Families that have connections with ISIS” is a term that surfaced in Iraq and Syria after the launch of operations to expel ISIS from its populated strongholds. The formal definition typically means one of the following:

- A member of the family, the father, or the entire family pledged allegiance and participated in logistics or combat activities;

- A member of the family, the father, or the entire family pledged allegiance but did not participate in any activity;

- A member of the family, the father, or the entire family pledged allegiance and coexisted economically or in the same circles with ISIS and did not participate in any action;

- A member of the family, the father, or the entire family were forced to pledge allegiance and did not take part in any action; or

- A family relocated from its original city and has a member included in one of the above categories.

In the areas of southern Ninewa and the Ninewa plain, ISIS families that have already returned to their cities and villages fall into one of three categories:

- Families that fled their cities and whose houses were looted, even if one of the family members was with ISIS, who are welcome to return to their communities. Occurrences of this were found in Muhallabiyah west of Mosul, and Shora and Hammam Al Alil south of Mosul;

- Families of ISIS members or supporters who informed the security forces about relatives who joined ISIS after the liberation of the city, who are outside suspicion. Such cases were found in Shora and Hammam Al Alil; or

- Families with members who had pledged allegiance to ISIS and remain alive, who are continuously harassed and displaced.

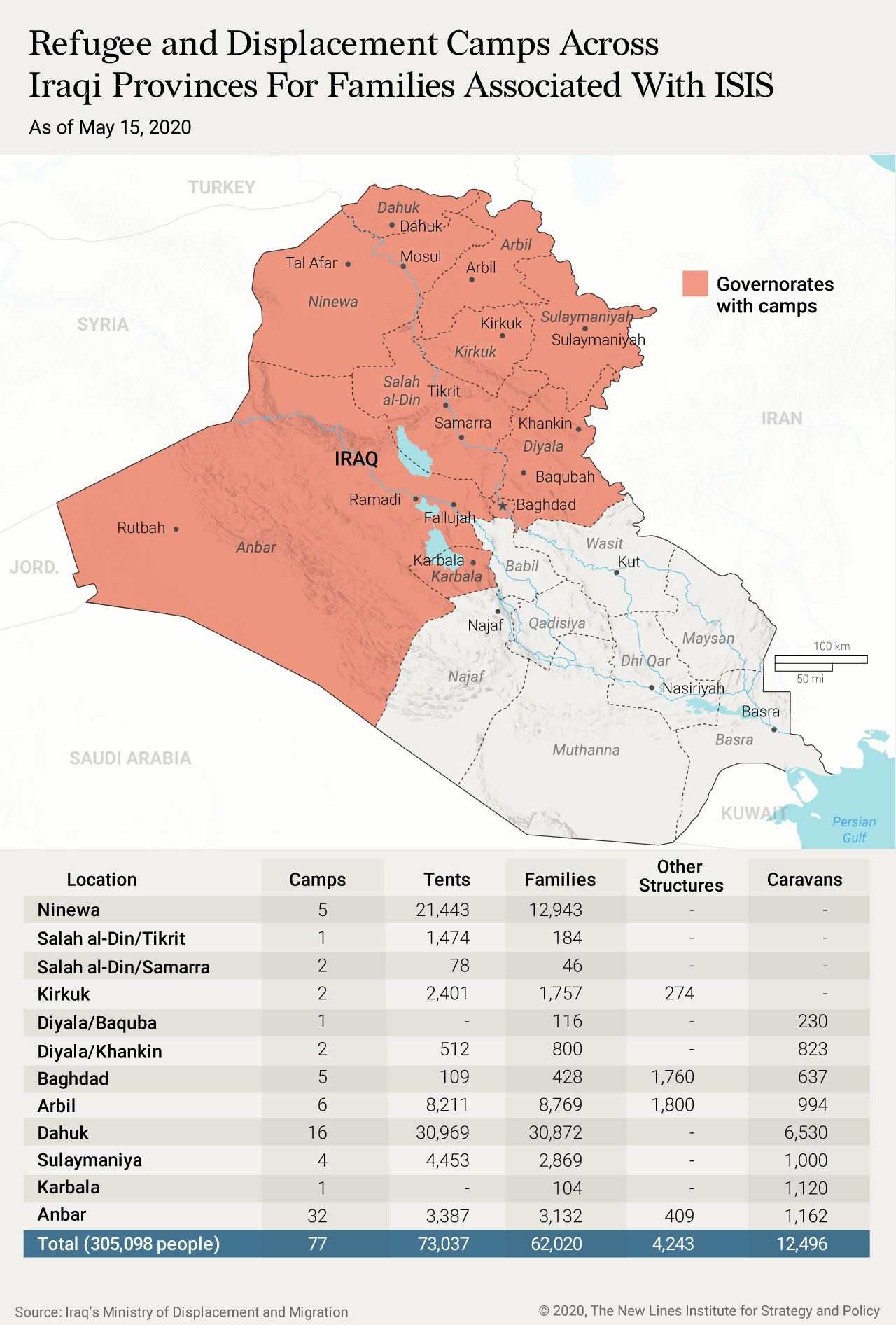

Iraqi authorities say more than 300,000 individuals with familial connections to ISIS live in camps spread out across at least 10 Iraqi governorates. Even though many of the displaced families returned to their areas of origin, many could not return to their actual homes and still live in nearby shelters. Additionally, 32,000 Iraqis live in camps for internally displaced persons (IDPs) in the north and east of Syria. (The problem of displaced ISIS families in Iraq dwarfs that of Syria, where displaced individuals from former ISIS territories are estimated to be a quarter to a third of the numbers in Iraq.)

An investigation by the Iraqi security and intelligence agencies linked a recent spike in ISIS attacks to ISIS militants’ displaced families returning to their home areas. Officials say they reached this conclusion after perceiving patterns related to the return of these families as well as information from tribal and local forces and the Popular Mobilization Forces operating in those areas.

The ostensible connection between terrorist activities and the return of ISIS families requires closer scrutiny. If it is correct, this presents a new security challenge as these families start to return to their villages and towns – and Iraq cannot address that challenge alone. If the connection is flawed, linking terrorist activities to families with members who had fought for ISIS is also concerning, as it could implicate and alienate a sizable portion of the Iraqi population. Both scenarios present security challenges that require the urgent support of all countries and non-governmental entities concerned about Iraq and ISIS’s broader reach.

Suspicions that ISIS families are enabling new attacks have made it more difficult to reintegrate these families with their original communities. Those suspicions likely contributed to their forced displacement, as happened in Shirqat, Muqdadiyah, and Abbara in Diyala. As detailed in a previous article, various reasons – including ethnic, sectarian, and security tensions – have prevented Sunni populations in more than 400 villages near the Iraqi-Syrian border from returning home in northern and western Iraq. Officials in liberated cities have expressed concerns about the difficulty of dealing with the complicated Iraqi tribal system, which local governments are sometimes incapable of navigating.

A Contentious Issue

This author approached various government officials and entities and asked them their views on family members with suspected links to ISIS returning to their communities as the security operations continue. The answers varied.

The governor of Ninewa, Najm al-Jubouri, supports the return of relatives of ISIS members. He said that he was not concerned if the issue took another year to be resolved and that the return depends on providing proper accommodation and services to speed up integration with the local community. If those conditions are met, families can return except for villages outside of Mosul in southern and western Ninewa – mainly for economic, social, and tribal reasons rather than legal or security concerns. He added that security clearances are required to exonerate these families, allow them to leave the camps, and protect them from legal prosecution. The security forces in Baghdad, he said, must issue a unified application to be available upon request within three days.

Even though tribes in Hadr (southwest of Ninewa) say they do not believe in punishing relatives of ISIS members simply because of the family association, ISIS has left behind deep wounds and broad schisms among the clans, many of whom have had their houses blown up or lost a loved one. According to former member of parliament Abdulrahman Al-Lwezy, members of ISIS used to go out, carry out operations, and then go back to their houses and families, who he believes should have interfered when they knew about their children’s terrorism activities. That view is often what residents cite as a reason for viewing the families as accomplices and refusing to allow their return.

In Tal Afar, west of Ninewa, the PMF has made the return of these ISIS families contingent on the government’s provision of services to victims’ families. Meanwhile, the victims’ families are enraged by what they consider unjustified delays of justice or compensation. Thus, the authorities face a two-sided problem that requires appeasing the victims’ families and welcoming back the families of the perpetrators.

The governor of Kirkuk, Rakan al-Jubouri, supports the families’ immediate return and says that Arab Sunni tribes, Sunni Turkmen, and the Kurds also endorse that policy. The main problem, he said, is with opposition from Shiite Turkmen and PMF; previous attempts to resettle families have failed in the villages of Amerli, Sulaiman Bek, Daqouq, Bashir, Dibis, and Tuz Khurmatu. To him, there are no legal, tribal, and economic obstacles for the return of these families; the main obstacles are security concerns from the PMF, especially Shiite Turkmen, even though the families in question have been cleared by the National Security Advisory and military intelligence.

In Hawija, southwest of Kirkuk, the tribes of Jubour and Shammar have decided in coordination with the PMF to force any family that included an ISIS member that had not previously surrendered to leave. These tribes and forces suspect these families of cooperating with ISIS members, including in recent attacks. Evacuating families falsely or rightly connected to ISIS in Hawija, in particular, will be a colossal effort, considering their large numbers.

The governor of Anbar, Ali Farhan al-Dulaymi, supports the return of the families and shutting down all IDP camps by the fall of 2020. He said no legal and security reasons exist for continued displacement, only social and tribal ones that can be overcome by enforcing law and getting pledges from the tribal leaders to stop harassing the returning families. Security clearances for suspected individuals in Anbar are now meaningless since all cases must be reviewed by the intelligence and the National Security Advisory, a body for security coordination established in 2004, for all of the families inside the camps. Those with suspected links have been referred to the legal authorities.

The governor of Salah al-Din, Ammar Jabr Khalil, also supports the families’ return. He said in his province, this was achieved in cooperation with the Iraqi security forces and tribal leaders in all of the province except Shirqat, north of Baiji, and Senniyah, and a small part of Yathrib and Auoja. He also asserted that no legal obstacles prevent the families’ return, only economic, security, tribal, and social issues. He said in his areas, there is no need for security clearances, as the tribal council, intelligence and the National Security Advisory have distributed a form to all of the families inside the IDP camps, and all were reviewed and cleared. The real struggle will be to provide economic aid for these families because their cities have been completely devastated.

The head of the Salah al-Din Provincial Council’s security committee, Jasim Jebara, stated that the tribes and families of ISIS victims cannot bear to talk about the return of these families and integrating the ISIS families with the community. Even those who got security and judiciary clearance are not welcome to start anew. With the recent increase in attacks, the ISIS families are in great danger.

The governor of Diyala, Muthana al-Tamimi, has halted operations to aid in the families’ return for two more years, citing legal, economic, tribal, social and security obstacles. Security clearances are needed to exonerate the families, and Baghdad should allow families to start that process. As in Salah al-Din, it is not safe for the families to return to Diyala, al-Tamimi said, especially with the recent spike in ISIS attacks. Moreover, Diyala’s Command of Operations and PMF have submitted a proposal advising to refuse the return of ISIS families until ISIS’s “vengeance” operations stop.

Reducing the Dangers

In light of current events, several precautionary measures will need to be in place to prevent a further displacement crisis and to decrease the levels of danger the ISIS families returning home could face from aggrieved or suspicious communities and militants.

The international community needs to provide financial aid and technical expertise to local governments and tribes. This will help manage the crisis and achieve integration and coexistence. The returned families must be trained and encouraged to provide reliable intelligence on their members who are still with ISIS.

Iraq’s federal authorities and the international community must contribute to the well-being of the victims’ families as a part of the resettlement program, with the help of the tribal leaders, to ease their suffering and allow them to accept the idea of the return of ISIS families.

Without resolving this issue, Iraq faces a ticking bomb that could blow up in the future as ISIS seeks to resurrect itself after the collapse of its caliphate. ISIS families make up a large portion of the Iraqi population and, unlike the families of foreign fighters, will be an issue for Iraq and its partners to deal with for a generation to come.

Dr. Husham al-Hashimi was a Nonresident Fellow with the Newlines Institute. Dr. al-Hashimi was a leading security expert focusing on Islamist movements who advised the U.S.-led coalition to defeat the Islamic State. Al-Hashimi was also a member of the Iraq Advisory Council, a group of experts based in Iraq. He Tweeted at @hushamalhashimi.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of the Newlines Institute.