The 2022 midterm national elections in November and the 2024 presidential election are place markers for potential acts of domestic terrorism and other forms of extremist violence in the coming months. While this analysis focuses on the run-up to the 2022 midterm elections, associated dynamics and potential outcomes provide insights for assessing political violence and unrest extending to the 2024 presidential election.

The current backdrop of increased threats to lawmakers and election officials, extremist candidates running for office, disinformation campaigns, and heated rhetoric – short-term conditions preceding the midterm elections – are raising the risk of domestic terrorism and other forms of extremist violence in the United States. For this reason, a repeat of the Jan. 6 Capitol insurrection or similar attack against a state capitol building cannot be ruled out. Mass shootings, bombings, arson attacks, and assassinations against politicians, police, government buildings, and the public are also plausible attack scenarios.

Far-Right Extremism

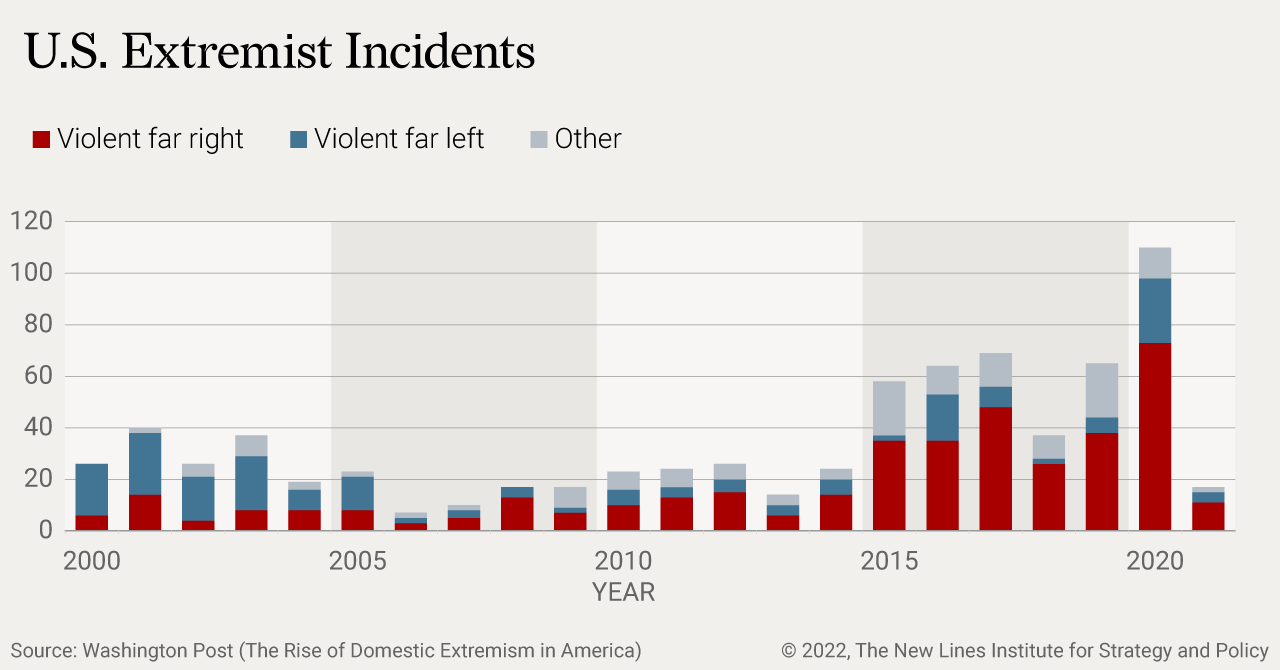

The current primary domestic nonstate threat to the U.S. and its territories is extremism on the far right. This type of extremism, primarily its white supremacist/nationalist and anti-government sub-movements, will continue to grow and pose greater public safety and national security risks for at least the next two years. The heightened risk environment is driven by several factors.

One element is the mainstreaming of extremist narratives. One of the most prominent narratives is widespread denial of the 2020 U.S. presidential election results. Often associated with rhetoric such as “Stop the Steal,” (or the “Big Lie,” by its critics) election denialism represents a crisis of fundamental democratic procedural legitimacy in the United States. Millions of Americans, overwhelmingly along partisan lines, hold the unsubstantiated belief that the election was manipulated by mass electoral fraud. While most individuals who subscribe to this belief engage in lawful civic activity, many support the idea of violence as a remedy to this perceived problem, leading small but dangerous numbers of individuals to make threats and/or attempt attacks.

Election poll workers, in what is traditionally considered a non-partisan volunteer civic position, have received hundreds of alleged violent threats, leading many to resign from their positions and discouraging others from volunteering in the first place. (There is some anecdotal evidence to suggest that this is also encouraging some individuals with strong partisan motivations to fill the gap in volunteers.) Illustrative examples of threats and acts of violence include the 2020 arrests of two armed individuals near a Pennsylvania vote counting center who believed fake ballots were deliberately cast to steal the presidential election; the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection at the U.S. Capitol complex; and the placement of two pipe bombs at the Republican and Democratic national committee offices in Washington, D.C., prior to the insurrection at Capitol Hill. More recently, between Oct. 17 and Oct. 22, 2022, there have been reports of vigilantes in Arizona’s Maricopa County engaged in alleged voter intimidation and harassment. Some of these individuals were reportedly armed and dressed in tactical gear while loitering in close physical proximity to secure voter ballot drop boxes and filming/photographing people depositing their ballots.

Threats against public officials extend to individuals elected to local offices. In many cases, violent clashes, armed intimidation, and heightened tensions have been observed at public meetings held by local governments concerning election outcomes, the public health response to the coronavirus pandemic, and how public schools should teach the history of racism in the United States. In response to these trends, Washington state legislators passed a bill that expands weapons restrictions on school grounds to include additional types of weapons, as well as expanding the restrictions to school board meetings (whether they held on or off school district-owned or leased property) and while picking up or dropping off a student. Threats also extend to state legislatures, which saw several armed demonstrations outside their facilities. Although lawful behavior, armed protests – particularly on or in close proximity to legislative facilities – are six times more likely to turn violent or destructive than other protests.

More than a year after the Jan. 6 Capitol insurrection, the U.S. Capitol Police have said that threats against lawmakers have reached an all-time high. In 2021, the U.S. Capitol Police investigated 9,625 cases of “concerning statements and threats” to members of Congress. Although there is evidence that indicates this is a bi-partisan phenomenon, much of this trend appears to be driven by the mainstreaming of violent rhetoric among political figures on the right end of the political spectrum that is not commensurately observed on the left end. Threats against members of Congress most recently manifested in a home invasion of Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi’s (D) San Francisco Bay-area residence by a far-right extremist.

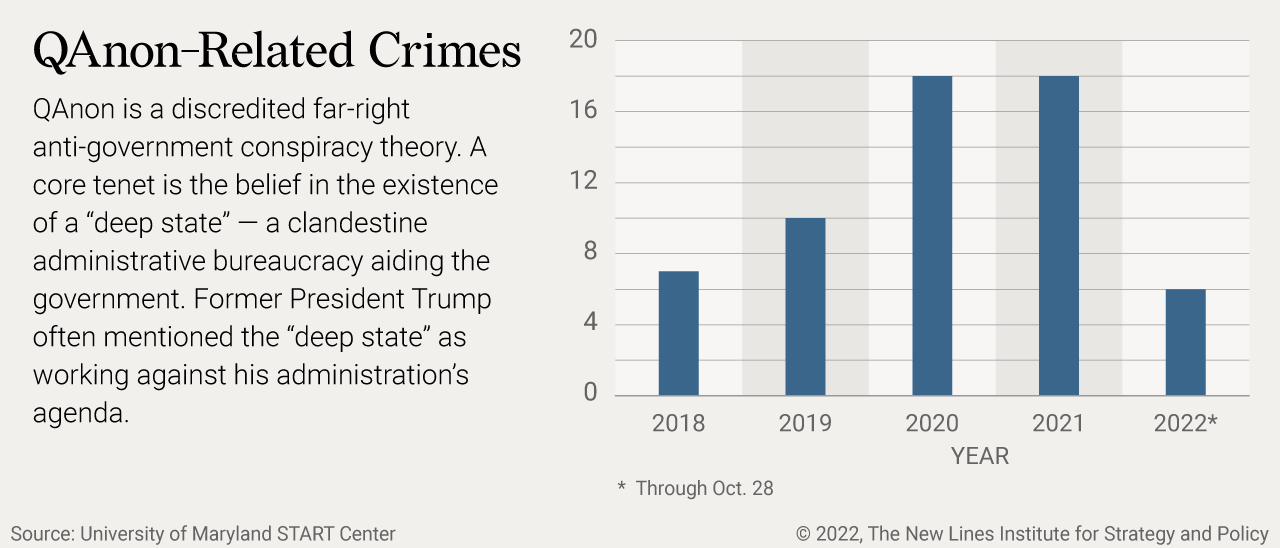

Meanwhile, conspiracy theory-centered anti-government extremist movements like QAnon have hyper-partisan elements to their belief systems. For instance, one of QAnon’s core tenets is the existence of a “Deep State” – members of the Democratic Party who are Satan worshippers and part of an elite global cabal that secretly controls the U.S. government and engages in child sex trafficking. In addition to perpetuating political polarization, the movement mobilizes individuals into political violence. Data from the University of Maryland’s START research center has identified at least 60 QAnon-related ideologically motivated crimes in the United States between 2018 and 2022, ranging from bomb hoaxes and other threats to successfully enacted incidents of violence. Twenty-five of these attacks (~41.6%) have occurred since the 2020 national elections.

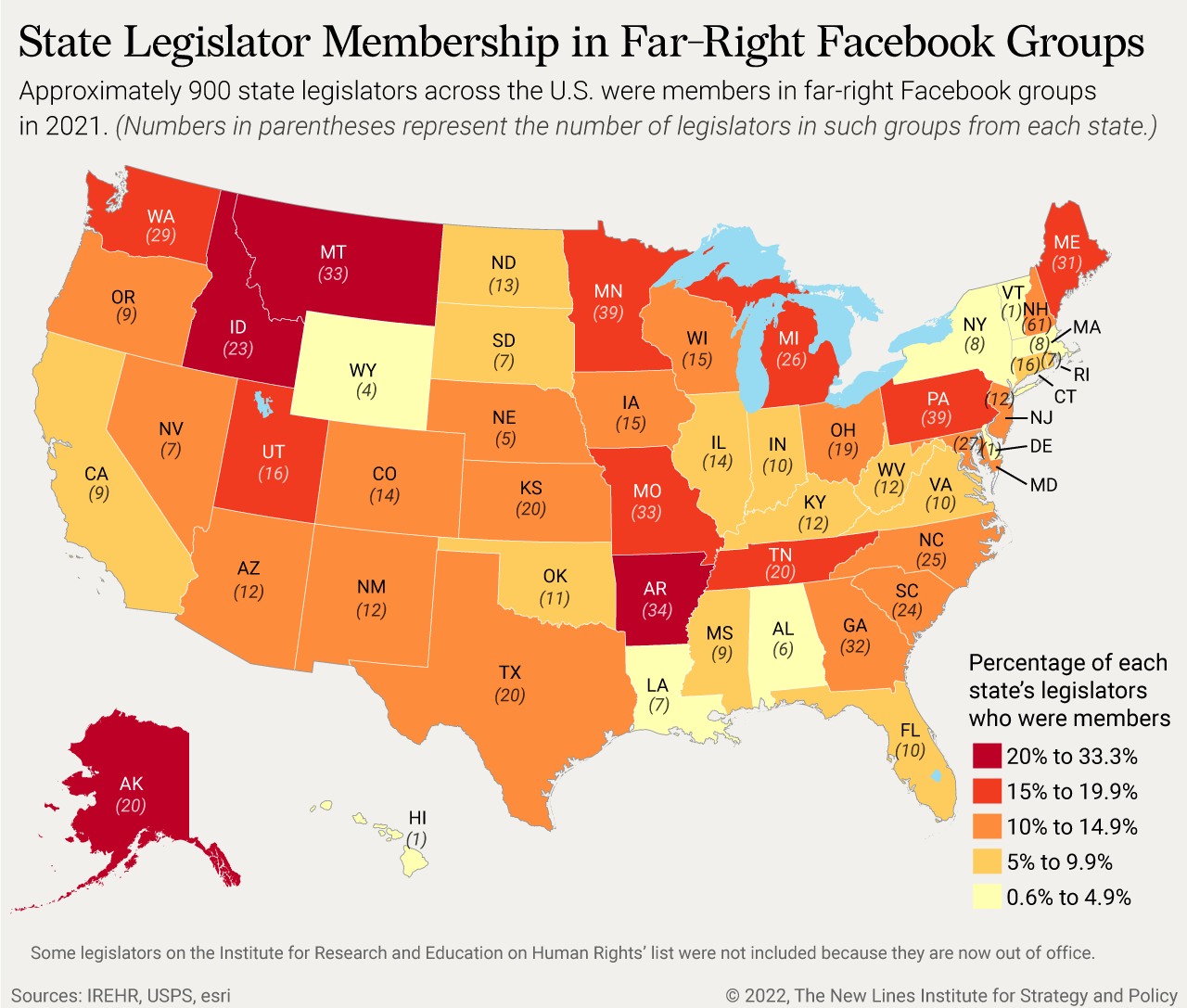

The mainstreaming of conspiracy theories like election denialism and movements like QAnon coincide with the rise of extremist candidates in local, state, and federal elections. In June 2022, the anti-hate watchdog Institute for Research & Education on Human Rights released a special report that “identified 875 state legislators serving in the 2021-2022 legislative period representing all 50 states who have joined at least one of 789 far-right Facebook groups. That is 11.85% of all state legislators in the country.” Further, nearly one year after the Jan. 6 insurrection, the Anti-Defamation League published an analysis identifying more than 100 far-right affiliated political candidates who claim to be running for political office in 2022. This list includes “candidates who promote extremist views, associate with extremists, and/or promote potentially dangerous conspiracy theories.”

At a national level, extremist candidates and elected officials at best contribute to an ever-polarized political environment that makes violence increasingly permissible. However, in some cases extremists in elected office may also constitute direct threats to public safety and national security, such as within the context of the growing far-right “Constitutional Sheriffs” movement. As these authors have noted in previous analyses, the presence of far-right actors in policing entities, including among elected county sheriffs, poses a potential insider threat to the integrity and confidentiality of intelligence/information sharing systems accessed by local, state, and federal law enforcement. More recently, many of these Constitutional Sheriffs are also not only failing to protect election poll workers from threats of violence but also are active supporters of election denialism, further imperiling American democracy’s procedural foundations.

Another variable is the recent changes in legislation, executive policy, and jurisprudence within the past year. These include reforms to firearms laws, reversing restrictive immigration policies from the previous administration, and the U.S. Supreme Court’s recent decision to reverse nationwide access to abortions previously allowed under Roe v. Wade. Historical trending further bolsters this assessment, which largely identifies a connection between far-right violent mobilization and legislative changes on hot-button socio-political issues frequently associated with America’s “culture wars.” For example, as the Biden administration continues to undo immigration policies enacted under former President Donald Trump, including the controversial “Title 42” action, far-right anti-government extremists and border vigilantes have steadily reinvigorated their activities along the U.S. border with Mexico. Similarly, immediately after U.S. Supreme Court 2022 landmark decision on abortion, far-right extremists like the Proud Boys and Three Percenters showed up to several pro-choice protests with firearms.

Yet another factor is extremists’ adaptations to governmental responses to the Jan. 6 insurrection. As of this writing, the FBI and Department of Justice have arrested and charged at least 919 individuals who participated in the attack, while many more are under investigation for suspected criminal acts during that incident. Further, the District of Columbia filed a civil lawsuit in December 2021 against the Oath Keepers and Proud Boys seeking to bankrupt both extremist organizations. While this will likely lead to the formal dismantling of both groups, their members are likely to adapt to their changing legal and operational circumstances. For their part, the Proud Boys have used a decentralized, chapter-based organizational structure for several years and have shifted their focus to hyper-local causes, like showing up to school board meetings, in response to increased scrutiny of their post-Jan. 6 activities.

Finally, there is Trump’s enduring influence. Although he is no longer in public office, he continues to exert direct and indirect influence on millions of Americans’ political perceptions and behaviors as a key figurehead who bears significant responsibility for mainstreaming and amplifying otherwise fringe views (e.g., election denialism). For many individuals, he has also become the central figure in an extremist de facto cult of personality (e.g., QAnon). Whether intended or not, Trump’s rhetoric and behaviors also influence individuals’ decisions to enact or stay away from political violence.

In the absence of some seismic event, such as a criminal conviction, Trump will likely continue to remain a key figure in public life for at least the next year, if not longer. In September 2022, Trump said he would pardon all incarcerated individuals linked to the violence associated with the Jan. 6 insurrection and issue an official government apology to these people if reelected, which hints at a possible run for the presidency in 2024. If he is criminally convicted, it will raise the short-term risk of violence as some of Trump’s most fervent supporters will seek to lash out in response to a perception of political persecution. Several incidents have foreshadowed this scenario. For example, an armed extremist attacked the FBI’s Cincinnati field office in August 2022. Evidence suggests the perpetrator, who died in a subsequent gunfight with law enforcement, was mobilized to violence after anger erupted among Trump and his supporters over a court-authorized search of his Mar-A-Lago residence, which many of his supporters see as the latest attempt by the “Deep State” to undermine him.

In the long run, beyond the 2024 elections, even if Trump is convicted of criminal wrongdoing and no longer in public life, the risk of far-right political violence will likely remain significant. The ideas and extremist movements that grew under Trump’s time as political candidate and president have gained institutional support and social momentum. In other words, Trumpism can continue to be a political force for the foreseeable future, both in its non-violent and violent manifestations, without the presence of Trump himself.

Far-Left Violent Extremism

Although violent far-right extremists were the focus of this assessment, far-left violent extremists pose a rising, although substantially less fatal, ideologically motivated threat. The threat from the far left includes, but is not limited to, violent anarchists, violent extremist strands of Black nationalism, and violent anti-fascist (“Antifa”) extremists.

The majority of attacks tend to be directed at property, and to the extent they are directed at people, they are mostly and intentionally non-fatal. Yet there have been notable cases of deliberate attacks against people, with some incidents resulting in fatalities:

- June 2016: Within a 10-day period, across two operationally unconnected incidents in Dallas and Baton Rouge, two individuals fatally shot a total of 8 police officers and wounded 12 others.

- June 2017: Five people were shot during a failed mass shooting directed at Republican members of Congress practicing at a baseball field in Arlington, Virginia, and the ensuing shootout between the shooter and law enforcement. The shooter and Louisiana congressman Steve Scalise were among those shot.

- July 2017: An individual engaged in a racial hate-motivated shooting spree in downtown Fresno, California, killing three people.

- July 2019: A failed armed assault targeted an Immigration and Customs Enforcement facility in Washington state.

- August 2020: A gunman killed a far-right Patriot Prayer counter-protester in Portland, Oregon.

- June 2022: Law enforcement prevented an attempt to murder U.S. Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh.

- September 2022: A fatal vehicle ramming attack at a street festival in McHenry, North Dakota, targeted a volunteer registered as a member of the Republican Party.

Moreover, while much of the rising trend of threats to members of Congress appears to be driven by right-wing actors, many of these threats also appear to be connected to individuals on the left end of the political spectrum. For example, a New York Times analysis of threats received by members of Congress in 2021 identified “nearly a quarter” that were made by Democrats against Republicans. (The same analysis found “more than a third” were made by pro-Trump individuals and other Republicans against Democrats and Republicans who were perceived to be insufficiently supportive of Donald Trump.)

Just as wider political context can at least partially explain violent mobilization among elements on the far right, they do the same for violent elements on the far left. In many cases this is in anticipation of, or response to, events of local and/or national political symbolism. The 2016 Dallas mass shooting came one and two days after the widely publicized fatal police shootings of Philando Castile and Alton Sterling, respectively, both of whom were Black men. Immediately preceding and following the reversal of Roe v. Wade, there were at least 24 incidents, all non-casualty outcomes, of vandalism or arson against facilities associated with pro-life actors. These attacks were claimed by a decentralized violent extremist movement calling itself “Jane’s Revenge.” The thwarted attempt to murder Brett Kavanaugh was significantly motivated by news that the U.S. Supreme Court was poised to overturn Roe v. Wade as well as a firearms regulation case also being heard by the court.

Other incidents had a strong local element to them. The Portland, Oregon, fatal shooting occurred during the latest outbreak of months-long violence between left-wing and right-wing protesters in the city.

Recommendations

As a recent U.S. Department of Homeland Security bulletin warns, “the United States remains in a heightened threat environment” that may become “more dynamic as several high-profile events could be exploited to justify acts of violence against a range of possible targets.” A volatile mix of conspiracy theories, disinformation, and an increase in polarizing political views among current and former politicians have intensified this threat environment. The following recommendations would mitigate the threats:

- Decrease verbal attacks against opposing political parties, politicians, and candidates. Politicians on both sides of the aisle should make every effort to tone down their rhetoric during their campaigns as it relates to the opposing party and associated politicians and candidates. Keep the rhetoric focused on issues and social as well as political stances, rather than verbally attacking or dehumanizing people.

- Safeguard and secure polling places against armed individuals, agitators, and other intimidating/harassment behaviors. Voting needs to be a peaceful process of exercising individuals’ constitutional rights. Citizens, voters, and political activists should not bring firearms or other weapons to polling stations. This type of behavior may deter voters. If armed individuals show up at a polling station, make every attempt to move them to a safe distance from voting locations where they are no longer a negative distraction to other voters.

- Defuse tensions at a local level. One way to accomplish this is for local community leaders and federal policymakers to invite and deploy teams from the Department of Justice’s Community Relations Service (CRS) to places with histories of communal tensions to prevent them from erupting into conflict, including violence. Dubbed “America’s peacemaker,” CRS is a non-investigative and non-prosecutorial agency within the Justice Department that offers facilitated dialogue, mediation, training, and consultation to communities confronted with tensions and “conflict based on actual or perceived race, color, national origin, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, religion, or disability.” Deploying CRS teams to places of communal tension not only provides opposing parties with a mediated means of communication but also provides fewer opportunities for extremists to exploit social conflicts into opportunities for instigating acts of violence.

- Mitigate the threat of extremist actors within law enforcement agencies. Consistent with these authors’ previous assessments, law enforcement agencies need to remove extremists from the ranks of policing entities. If removal is not possible, agencies are urged to take administrative and other departmental action to identify and mitigate the potential impacts the presence of extremists may have. Furthermore, in the case of the Constitutional Sheriffs movement, a situation where extremists have ascended to positions of law enforcement leadership through election, local civil society actors and elected officials can lawfully monitor and provide oversight of their activities – especially in connection to polling places and electoral processes. In cases where there is evidence of potential criminal wrongdoing, local actors are urged notify the FBI’s Civil Rights Division.

- Enhance protection for public officials. The Office of the Director of National Intelligence published guidance to first responders ahead of the 2022 midterm elections that offers ideas for mitigating and responding to threats against public officials. These considerations include information sharing and situational awareness; planning, coordination, and training of first responders; and online and physical personal security measures. These authors agree with these recommendations and encourage physical security upgrades to local, state, and congressional legislative facilities to ensure lawmaking processes are not disrupted by threats or acts of political violence.

Alejandro J. Beutel is a nonresident fellow with the New Lines Institute who studies non-violent and violent extremist far-right and Islamist movements. Beutel is a former Senior Research Analyst at the Southern Poverty Law Center and a former Researcher for Countering Violent Extremism at the University of Maryland’s National Consortium for the Study of & Responses to Terrorism. He is pursuing a PhD in Criminology and Criminal Justice at the University of Massachusetts at Lowell.

Daryl Johnson is one of the foremost experts on domestic extremist groups in the United States and a nonresident fellow with the Newlines Institute. Beginning his career as a civilian in the U.S. Army, Johnson has held a number of government positions, most recently as senior analyst at the Department of Homeland Security. He is also regularly cited, featured, or quoted in media covering domestic extremist groups in the United States, including the New York Times, Washington Post, Wall Street Journal, Newsweek, National Public Radio, MSNBC, CNN, and NBC Nightly News, among many others. He is the author of “Hateland: A Long, Hard Look at America’s Extremist Heart” (Prometheus Books, 2019) and “Right-Wing Resurgence: How a Domestic Terrorism Threat Is Being Ignored” (Rowman & Littlefield, 2012).

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not an official policy or position of the Newlines Institute.