Listen to article

Militants in Southeast Asia continue to be a security concern for governments and law enforcement agencies. The Islamic State group presented a unique threat to the region with its attempt to form a caliphate, especially after its defeat in Iraq and Syria in 2017 fueled speculations that it would attempt to use Southeast Asia as a second front.

However, the capabilities of the Islamic State generally have been overstated. The success of the group’s global ambitions is heavily dependent on its capacity to exploit security vacuums precipitated by local grievances, and it has had difficulty adapting to local issues while trying to unite and support disparate players – whose internal dynamics often hinder their own operational and organizational capabilities – without a clear uniting purpose in a strong security environment. Because the bulk of the Islamic State movement in Southeast Asia is energized by local insurgencies, the group’s caliphate ambitions have lost their luster.

The Southeast Asian-Afghanistan Militant Links: Then and Now

The Soviet-Afghan war of the 1980s played an important role in producing a generation of Islamist militants in Southeast Asia, attracting a legion of Muslim foreign fighters who saw the war as their religious duty to become mujahideen. It was estimated that hundreds of militants were trained in Afghanistan between 1985 and 1994. Groups like Jemaah Islamiyah, the Moro Islamic Liberation Front, and Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) formed and secured strong links with al Qaeda through shared combat experience. The Islamic State’s global caliphate branding appealed to many militants and aspiring extremists in the region, despite their falling out with al Qaeda. ASG soon pledged allegiance to the Islamic State along with the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters (BIFF) and rebranded as the Islamic State-East Asia and Islamic State-Maguindanao, respectively. The Maute Group also pledged allegiance and became the Islamic State-Ranao.

In contrast, Jemaah Islamiyah, which has been an influential transnational jihadist movement, remained firmly affiliated with al Qaeda and its former Syrian offshoots, Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham and Huras ad-Din, and had sought to send their members to Syria to train with Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham. However, when Jemaah Islamiyah’s spiritual leader Abu Bakar Ba’asyir, who also founded Jemaah Ansharut Tauhid, pledged allegiance to Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, it provoked a rift amongst his followers. This sudden declaration of allegiance had created an institutional crisis among Ba’asyir’s followers, given that Jemaah Islamiyah considers the Islamic State to be extremists, leading to the group’s splintering and the formation of Jemaah Ansharut Syariah (JAS), which ideologically favors al Qaeda but emphasizes evangelism and social services over violence.

The Taliban’s return to power in Afghanistan in August 2021 had ignited speculations of an increase in radicalization in Southeast Asia that could materialize into major domestic attacks or inspire foreign fighters to travel to Afghanistan. However, events in Afghanistan so far have had little effect on groups in Southeast Asia because extremism in the region is no longer ideologically or logistically connected to Afghanistan, even in pro-al Qaeda groups.

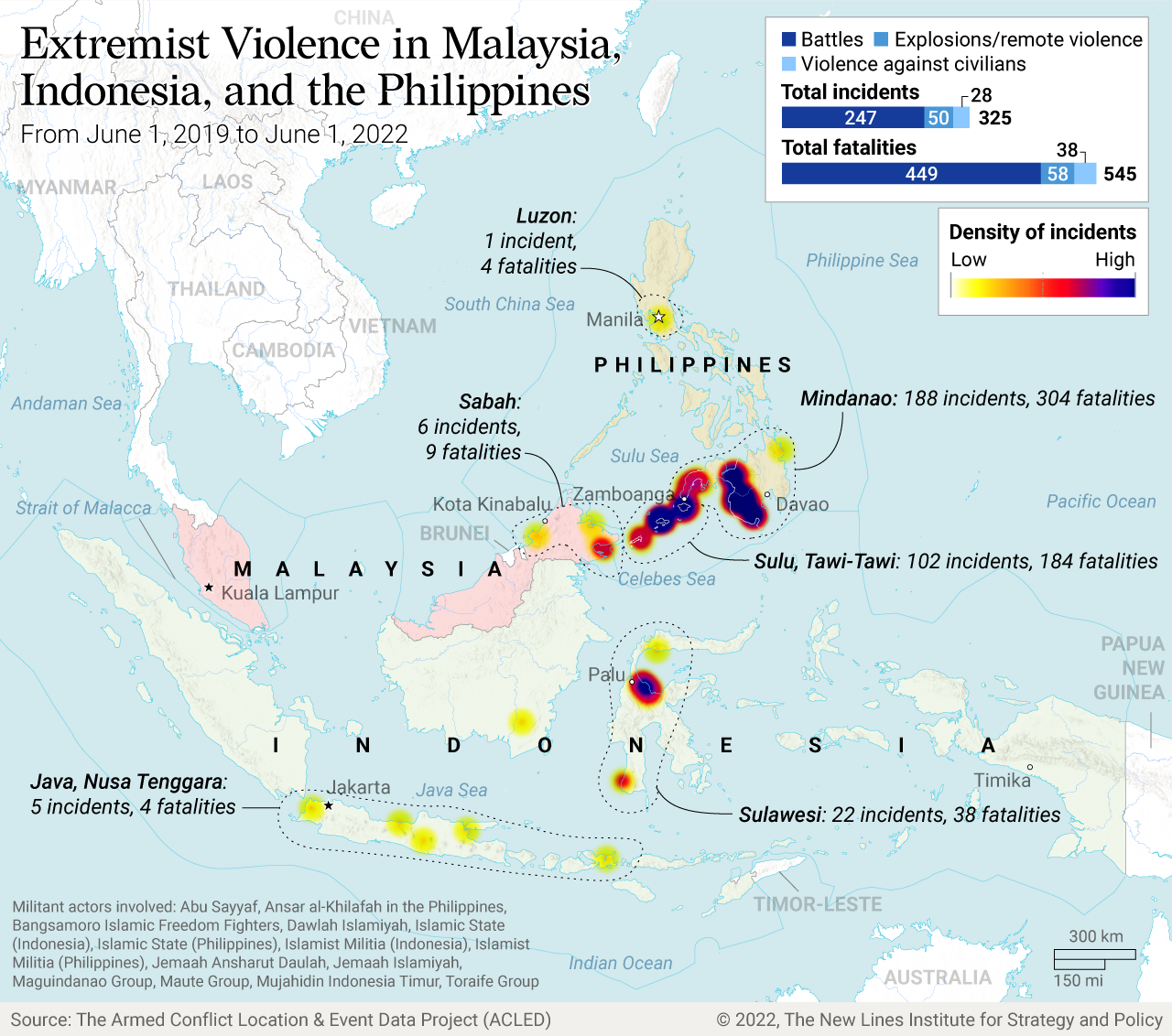

There is no logistical link between Afghanistan and Southeast Asia because there are no well-structured allies in the region to mobilize or facilitate logistical support; militancy in the region is still largely driven by historical and domestic factors such as anti-colonial roots and secessionist goals. Militant activities in the region remain largely focused in the southern Philippines and Indonesia. Meanwhile, the Islamic State continues to struggle against military actions in Iraq and Syria, and some of its fighters have decamped to the Islamic State-Khorosan to fight against the Taliban. The February decapitation strike that killed Islamic State leader Abu Ibrahim al-Hashemi al-Qurashi in northern Syria dealt a serious blow to the group’s rebuilding narrative and attempts at a resurgence. Like al-Baghdadi’s death, it is unlikely that al-Qurashi’s killing would inspire revenge attacks in Southeast Asia.

Furthermore, the bitter rivalry between al Qaeda and Islamic State-Khorosan may have diluted their influence in Southeast Asia, as there is no clear common goal to galvanize the global ummah. Also, Islamic State-Khorosan’s own ambiguous goals seem focused on expanding its reach and influence in South and Central Asia, so there is no indication they would attempt to expand or evidence that they have the resources to facilitate training and build connections. The group’s members are mostly from South Asia and Central Asia, and many are former Taliban – to the point where some analysts have described them not as a province of the Islamic State but as a breakaway faction of the Taliban

The fluid trajectories of militant activities in Southeast Asia had contributed to the revival of the popular fallacy that the region was a “second front” for Islamist extremism. As key local militant groups pledged adherence to the Islamic State, it appeared the group was gaining a foothold, but the region’s geographical importance was overblown. Unlike the close working relationship al Qaeda had nurtured with the region’s key Islamists and connections formed through their training program, the Islamic State largely relied on its centralized media operations (which later became decentralized) to propagate its propaganda to entice followers to either travel to Iraq and Syria to participate in their state-building effort or plot domestic attacks.

Operational Capabilities

Religious extremism appears to be the primary driver for militant movements in Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines. The sporadic attacks perpetrated by pro-Islamic State groups in Indonesia and the Philippines despite the disintegration of the caliphate provided the impression that these groups’ capabilities are ameliorating due to their operational tempo.

The COVID-19 pandemic had posed challenges to their resilience, frustrating their efforts to take the opportunity to regroup, plot attacks, drive narratives that encourage divisiveness, recruit, and exploit vulnerabilities as local authorities prioritized the health crisis. Instead, the pandemic impaired their movements, capabilities, and access to resources.

Some groups in Southeast Asia have struggled to fund themselves, with the pandemic making it difficult for their members to earn income, hampering any fundraising for militant activities. Other groups that are well-structured with coherent funding strategies are more adaptable in comparison. While the pandemic may have encumbered attempts at facilitating attacks, militants are sustaining themselves in other ways.

Militants in the Philippines

Given the decades of violence that plagued Mindanao, compounded by fractious politics and the Sulu arms trade that fostered conflict and instability, the southern Philippines has long been described as a breeding ground for Islamist insurgency. Since 2000, radical Islamist groups have carried out numerous attacks, including major bombings, mostly in the south of the country. Transnational terrorist organizations such as al Qaeda and Jemaah Islamiyah have also been linked to activities in the Philippines. The southern Philippines had served as training ground to complement al Qaeda and Jemaah Islamiyah’s joint training program since the 1990s.

Militancy in Mindanao has been declining since 2020 for a number of reasons. The government’s military actions in Basilan and Sulu against pro-Islamic State factions like ASG have been aggressive. ASG has also fragmented into smaller, rival subgroups, often along familial or criminal fault lines, and many members have surrendered to security forces. BIFF is also suffering for many of the same reasons.

Consequently, militant members were weary from their territorial defeat, leadership decapitations, loss of bases and stronghold deprivations, resulting in a rise in militant surrenders. Approximately 347 militants, including members of ASG, BIFF, and Maute Group, surrendered to Philippine security forces by the end of 2020, while 130 were killed. The pandemic has also presented the government with an unanticipated opportunity to offer disarmament and demobilization incentives.

The recent appointment of the so-called Islamic State emir for Southeast Asia, as well as two May 31 bombing attacks in Basilan that went unclaimed, could indicate that militants in this restive part of the world are attempting to reclaim their pre-COVID momentum and launch a new wave of attacks. These actions should not, however, be confused with a measure of a group’s effectiveness or strength. Until the new emir demonstrates strategic patience rather than overestimating the utility of violence in his new role, doctrineless strikes might only function as poor capacity-signaling.

Militants in Indonesia

Between 2002 and 2010, Jemaah Islamiyah was the most dangerous terrorist network in Southeast Asia, responsible for a series of terrorist attacks. As a response to the Bali bombing, the Indonesian National Police formed an elite counterterrorism unit known as Densus 88 (“Detachment 88”) that led concerted operations in Indonesia and the region. The raids resulted in arrests and eliminations of key Jemaah Islamiyah operatives and bombmakers, diminishing the group’s operational effectiveness.

Nevertheless, the group still is a medium- and long-term threat despite not having been publicly involved in recent acts of violence. Jemaah Islamiyah was able to circumvent the pandemic’s impact on its operations and revenue streams by inventing nongovernmental charity organizations and orphanages and planting charity boxes in shops and minimarkets across Indonesia to solicit alms from unsuspecting donors to finance the group’s activities, including their members’ travel to Syria for training with the Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham and legal fees for members on trial. The Syam Organizer, one of Jemaah Islamiyah’s charity fronts, raised over IDR 1.9 billion ($136,000). Jemaah Islamiyah has lately sought to gain legitimacy via the electoral process by masquerading as a political party and embedding one of its members in the clerical council of the nation.

While Jemaah Islamiyah is experiencing a decline in violence, a new Islamic State affiliate network known as Jemaah Ansharut Daulah (JAD) emerged in 2014. Led by Aman Abdurrahman, JAD quickly earned notoriety for attacks on Christians, including the 2018 triple church bombing in Surabaya, the 2019 suicide bombings that targeted a cathedral in Jolo, and the March 2021 bombing of Makassar’s cathedral on Palm Sunday. In contrast to Jemaah Islamiyah’s centralized and hierarchical organization, JAD’s lethality is attributed to its decentralized nature, usually family units, with eight regional commands across Indonesia. Compared to Jemaah Islamiyah’s meticulous strategizing, JAD’s approach is more opportunistic and disregards long-term impacts. Because of this, Indonesian authorities focused their efforts on targeting and arresting Islamic State cells, such as JAD. The expansion of Indonesia’s counterterrorism bureaucracy contributed to the successful capture of key leaders and facilitators as a result of the crackdowns.

East Indonesia Mujahideen, the other active pro-Islamic State organization in Indonesia, operates in the Poso regency of Central Sulawesi. In 2014, the group was the first in the country to pledge bay’ah to the Islamic State. Despite commander Santoso’s death in 2016, the group has made news after taking advantage of the pandemic to increase its operational tempo and instigate a sectarian conflict, crediting their ability to secure financial aid and food supplies to popular support from local communities and distrust for authorities due to the region’s history with sectarian conflict in the early 2000s.

East Indonesia Mujahideen is capable of spreading fear when necessary to intimidate locals into submission despite its small size. The group’s resilience stems from its narrative that it controls territory in Poso and can thus attract outsiders, funding, and support from other militant networks.

However, the group recently splintered and has been experiencing severe losses, making it more difficult to endure without leadership. In 2021, Densus 88 made 370 terrorism-related arrests, which included 194 Jemaah Islamiyah members, 16 East Indonesia Mujahideen members, and five JAD members.

Militants in Malaysia

Although terrorism is rare in Malaysia compared to Indonesia and the Philippines, Malaysia is a well-known transit point and an established safe haven for terrorist groups. One of the earliest grassroots extremist movements in the country can be traced back to Zainon Ismail, a veteran of the Soviet-Afghan war who founded Kumpulan Militan Malaysia (KMM) in 1995. Under the leadership of the more radical Zulkifli Abd Hir, KMM quickly progressed to violence, with the ambition of replacing the government with a more Islamic one. Counterterrorism actions prompted by the Bali bombing led to the disintegration of KMM and Jemaah Islamiyah’s degradation. Key members such as Yazid Sufaat, who was developing anthrax as a bioweapon for al Qaeda, were arrested, and bombmaker Azahari Husin was killed.

However, as these groups declined the Islamic State began attracting Malay-Muslim supporters. The Malaysian government estimated over 100 Malaysians have joined the Islamic State in Syria since 2013, and when the group began losing territory, it urged followers to carry out homegrown attacks in their own countries. Moreover, Indonesian and Malaysian militants in Syria formed a specialized military unit known as Katibah Nusantara (“the Archipelago group”) to facilitate Islamic State outreach in Southeast Asia, and they even managed to mastermind the 2016 Jakarta attacks from Raqqa.

The 2016 Movida Bar grenade attack, carried out by local Islamic State operative Muhammad Wanndy Muhammad Jedi, prompted fears that the group was about to ramp up its attacks in Malaysia. But the attack, and Wanndy’s subsequent chaotic leadership, failed to galvanize others for a sustained campaign – a reflection of local actors’ poor resilience and inability to organize effectively. Successful terrorist campaigns involve more than just motivation through violence; fundamentally, even coercive tactics need to be part of coherent strategies, delivered by an organization that is fit for the purpose. Such a campaign’s success relies on achieving legitimacy through mass support – which local Islamic State actors did not have. Furthermore, prior to the recent repeal, counterterrorism laws in Malaysia were powerful enough to allow law enforcement officers to detain suspects for further investigations over terrorism-related offences. Over 500 suspects were arrested in 2019 alone, but that number dwindled to seven in 2020 due to nationwide Movement Control Order imposed by the pandemic.

Malaysia has been experiencing growing Islamic fundamentalism for the past few decades, with ultra-conservative movements pushing for reforms toward a harsher, more rigid model of Islam. There is a stronger likelihood that extremists will adopt a mainstream political mechanism with which to introduce the Afghan Taliban’s model of harshly interpreted shariah, much like Jemaah Islamiyah’s approach in Indonesia, rather than a violent movement that could risk repelling popular support.

Organizational Challenges

Militant groups in Southeast Asia are confronted with the organizational problems of waging collective violence, and pro-al Qaeda militant groups are learning to focus on local conflicts for legitimacy and to avoid antagonizing the West. Meanwhile, East Asian Islamic State franchises are seeking to recreate their previous “success” by urging fellow militants to travel to the Philippines. However, these groups also have struggled to establish an effective regional coalition because each comprises individuals with distinct local goals and grievances. Furthermore, the new Emir’s success will be determined by his ability to value patience over hasty strikes.

It is also becoming increasingly difficult for militants to mobilize effective coercive tactics, particularly in states with strong security environments. State and regime strengths, as well as competent police intelligence and an efficient military, continue to factor into this calculus. For example, Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines all have anti-terrorism legislation that empowers law enforcement to conduct preventive arrests for terrorism-related offences and allows for extended detention.

The strength of these militant groups lies in their ability to frame and disseminate their narrative. Transforming mass support into active participation is essential to promote insurgent causes, but these militants have often failed to understand the importance of this process. Faced with the Caliphate’s demise and failure of Marawi Siege, they are seen as espousing a meaningless ideology. Malaysia’s repatriations of foreign fighters from Syria also have helped drive home their experiences, which highlighted the harsh realities of the Islamic State’s empty promises, discouraging others from joining.

These groups’ shift from centralized organizations to decentralized networks, such as JAD, is an indication that they are hoping to engage in diverse actions while coping with challenges in maintaining their operational lethality due to improved security environment. Militants have been known to restructure when they think they will become safer and more secure, but instead they become more fragile as they lose agility, resilience, and efficiency.

When groups expand to form cells, this is a sign that they are having trouble coping with counterterrorism pressure. For instance, JAD betray their strategic inadequacies by orchestrating attacks when they are weakest for the sake of capacity-signaling. Many of these groups also have splintered, and it is likely that they will experience further fragmentation. Case in point, JAS’s splintering from Jemaah Ansharut Tauhid suggested that they were unable to agree on the use of violence to achieve political ends, and JAS wishes to seek legitimacy. Finally, terrorist groups need safe havens where they can thrive in states with weakened governance while targeting other areas; it is likely they will seek shelter in Malaysia.

Government Counterterrorism Response

Following consultations with key government stakeholders and civil society organizations, Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines each developed and implemented a National Action Plan on Preventing and Countering Violent Extremism that took “whole-of-government” and “whole-of-society” approaches to combating extremism as part of their counterterrorism response. These countries are also working closely with the U.S. through bilateral and multilateral security cooperation. Increased information sharing agreements, reciprocal cross-border assistance, and subregional efforts like the Trilateral Cooperative Arrangement and Our Eyes Initiatives can be leveraged for the benefit of democratic governments’ counterterrorism efforts. Focusing on militant ideology, message, and resonance, in addition to military activities and law enforcement, is only half of the battle. Given that the U.S. has been funding efforts to support their Southeast Asian partners, it would be beneficial to also provide these nations with enhanced monitoring and assessment capabilities to evaluate their progress and mitigate abuse of these funds such as corruption, as well as continual skill and knowledge exchange.

Real and Imagined Threats

While there remains an extant extremist threat in Southeast Asia, the collapse of the Islamic State caliphate in Iraq and Syria and the re-emergence of the Taliban government in Afghanistan do not equate to increased likelihood of politically or religiously motivated violence in the region. The links between groups are, at most, aspirational, based on some shared ideology; actual management and execution of operations remain local. Given the region’s fragile democracies, the greatest risk currently being overlooked is the possibility that extremists can play the long game by eschewing violence as a strategy and participating in legitimate ultraconservative political movements, thereby leveraging and subverting democratic tools to achieve their ends.

Although many militant groups cannot outlast these governments even with their flawed democracies due to their robust security environments, expanding communal rifts will continue to provoke conflict. Since local actors and cells are bonded by common grievances and not by the notion of a global caliphate or an alliance with the Taliban, counterterrorism measures must also target militants’ internal social networks. Idealistically, this may be accomplished by addressing issues such as widening socioeconomic differences and rising social alienation. Nonetheless, tackling social issues necessitates accountability at all levels, and governments in the region must be prepared to participate in an open dialogue with vulnerable populations and be transparent in their counterterrorism arrests.

Munira Mustaffa is a Non-Resident Fellow at the New Lines Institute, and a Fellow at Verve Research where she focuses on the relationship between militaries and societies in Southeast Asia. Mustaffa has worked as a security and intelligence practitioner, and researcher in the private, government and military sectors. Her commentary and work on terrorism, extremism, and cyber warfare have been published by several publications, including NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence (STRATCOMCOE) and Global Network on Extremism and Technology (GNET) Insights. She earned a masters in Countering Organized Crime and Terrorism from the University College of London and tweets at @muniramustaffa.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of the New Lines Institute.