In 1945, the United Nations was founded to “save succeeding generations from the scourge of war” and to promote justice, human rights, and social progress. In its nearly 80-year history, the U.N. has developed an array of tools to advance the collective good, and under the authority of the U.N. Security Council, the organization has facilitated the international community’s response to countless threats to international peace and security, particularly through the deployment of U.N. peacekeeping operations.

U.N. peacekeeping has been, and continues to be, one of the international community’s most effective mechanisms for responding to conflict; however, the peacekeeping enterprise is affected by the fraught dynamics within the U.N. Security Council and waning confidence among members and nonmembers alike. These factors affect the efficacy of peacekeeping, fueling the narrative that the tool is outdated. U.N. peacekeeping remains a remarkably effective tool for reducing the duration of conflict, the harm to civilians, and the likelihood of recurrence, and it continues to represent the remarkable power of collective action to promote international peace and security. Mitigating conflict is important for both international security and U.S. national security; therefore, U.S. policymakers should view U.N. peacekeeping as a valuable tool of U.S. foreign policy and engage proactively and consistently with the U.N. to promote the protection, evolution, and thoughtful application of this tool.

What is U.N. Peacekeeping?

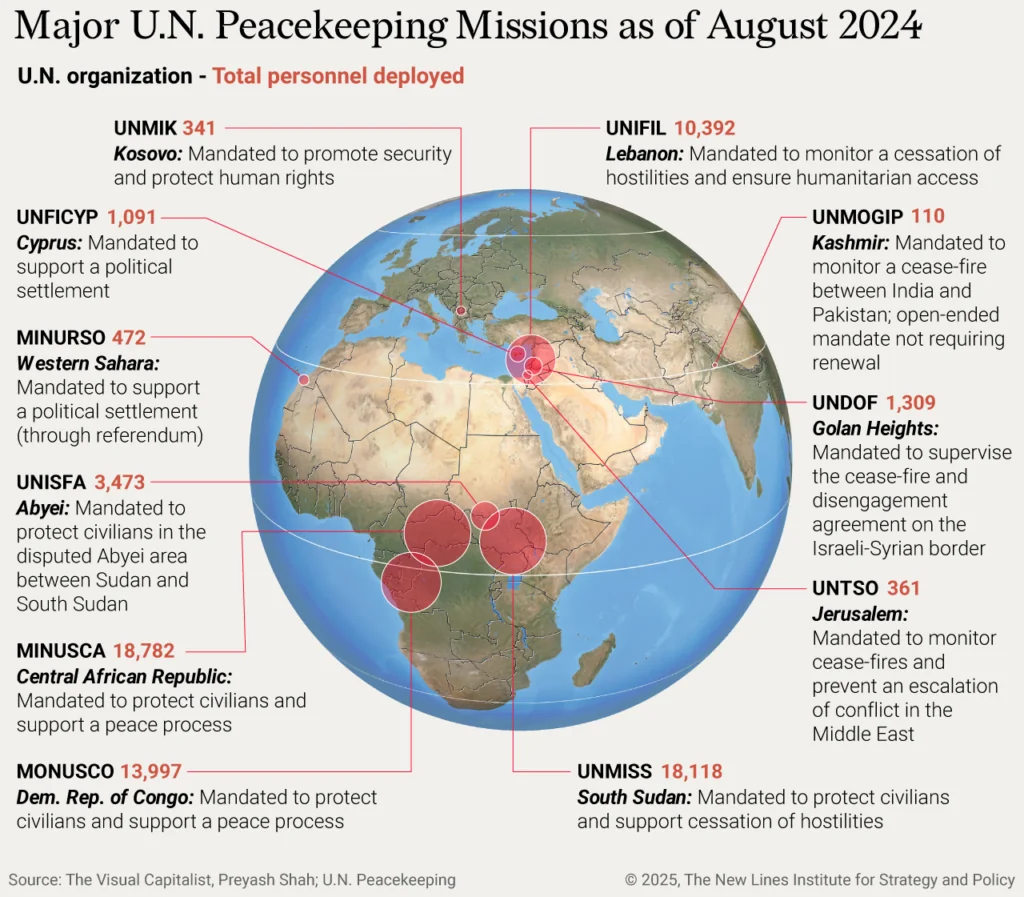

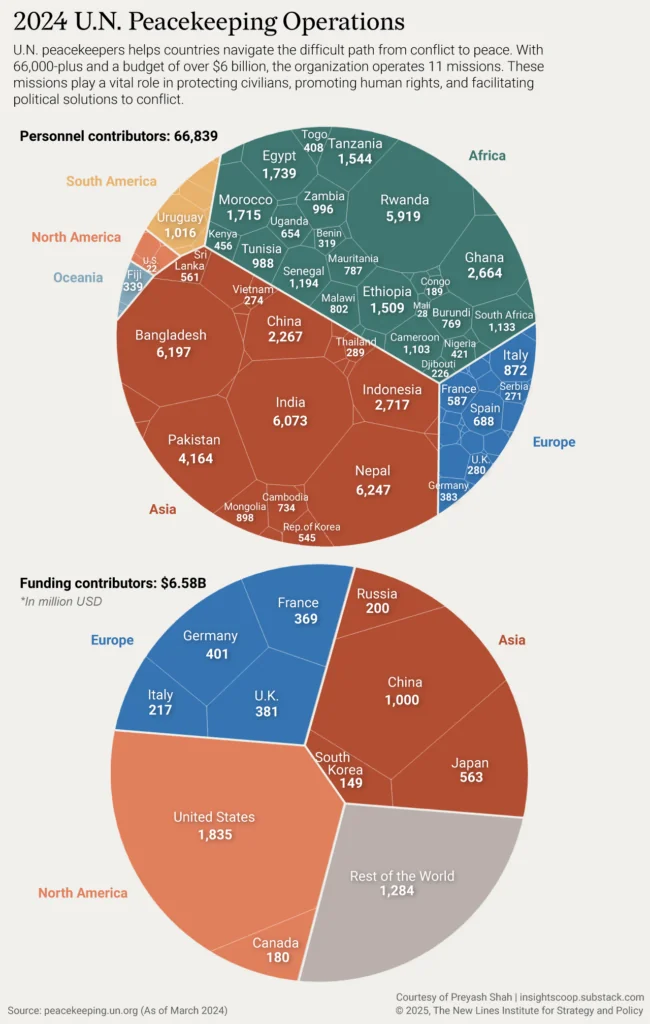

U.N. peacekeeping is designed to help countries in conflict transition to peace through a range of activities mandated by the U.N. Security Council. It is not an enforcement tool, but robust mandates may be required to protect civilians and create the necessary conditions for a genuine peace process to advance. Three interrelated and mutually reinforcing principles govern peacekeeping operations: 1) consent of the parties; 2) impartiality; and 3) nonuse of force, except in self-defense and defense of the mandate. U.N. peacekeeping missions comprise military and civilian personnel from 121 countries, referred to as troop- and police-contributors, or T/PCCs. Many of the largest T/PCCs, in terms of people contributed to peace operations, lack the financial resources to deploy well-trained and well-equipped personnel into the field. At the same time, many of the largest financial donors to peacekeeping do not contribute large numbers of troops, or any troops; therefore, in recognition of the universal value of high-performing peacekeeping missions, partnerships between donors and T/PCCs have emerged to facilitate more capable missions. The United States is the world’s largest financial contributor and capacity-building partner.

Studies show that U.N. peacekeeping operations have been effective at reducing the duration of conflict and preventing its recurrence while promoting inclusive peace processes and more durable political solutions. It is important to note, however, that peacekeeping missions are not designed to solve conflicts but rather to create the space necessary for political solutions to advance and to support the parties in negotiating these solutions. The earliest peacekeeping missions were authorized under Chapter 6 of the U.N. Charter, with a focus on peaceful dispute resolution through negotiations and mediation. In response to changing security dynamics and an increase in intrastate conflict, the Security Council has authorized more recent missions under Chapter 7, allowing coercive action in response to threats to peace and acts of aggression.

While the image of peacekeeping includes blue helmeted troops on patrol, these missions are made up of military and civilian personnel charged with pursuing a broad range of activities aimed at reducing violence and promoting an inclusive peace. Many multidimensional missions authorized under Chapter 7 are mandated to carry out Community Violence Reduction projects that include supporting local women entrepreneurs, facilitating community dialogue, raising awareness about human rights, and considering the needs of women, youth, religious minorities, and other marginalized populations in the design and implementation of these projects. These missions also support national disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR) programs, facilitate the delivery of humanitarian aid, and support elections when mandated to do so by the Security Council.

The U.S. Cost of U.N. Peacekeeping

The annual budget for U.N. peacekeeping missions for fiscal year 2023-2024 was $6.1 billion, which is 0.5% of global military spending. The largest and most expensive mission is currently MINUSCA in the Central African Republic, with a budget of $1 billion and 17,000 peacekeepers on the ground. Since U.N. peacekeeping operations are the primary tool of the international community for responding to conflict, U.N. member states finance the peacekeeping enterprise through assessed contributions, calculated based on a country’s gross national income, debt level, per capita income, and general ability to pay. This method of burden sharing ensures that the countries that wield the most influence within the U.N. system are footing the largest portions of the bill. It must not be forgotten that many of the countries making much smaller financial contributions are paying with the lives of their citizens. Based on U.N. peacekeeping assessments, the United States is the largest financial supporter of U.N. peacekeeping operations, contributing $1.37 billion in fiscal year 2024. For perspective, the fiscal year 2024 Department of Defense funding bill totaled $824.3 billion.

While the U.S. contribution is not insignificant, it pales in comparison to the alternatives. Studies from the U.S. Government Accountability Office determined that U.N. peacekeeping can be up to eight times more cost-effective than deploying U.S. troops to a conflict zone. This does not even factor in the political cost of a U.S. intervention, which could be quite high depending on the geopolitical dynamics surrounding the conflict, and difficult to justify to the American taxpayer. Many of the conflicts addressed through U.N. peacekeeping may not appear to have a direct effect on U.S. national security; however, the potential for regional conflict, humanitarian crisis, the expansion of terrorist networks, and other manifestations of instability, justifies international intervention and underscores the need for an impartial arbiter of peace.

In recognition of the U.S. national security benefits derived through high-performing U.N. missions, the United States seeks to maximize the return on U.S. financial investment in U.N. peacekeeping by building the capacity of T/PCC countries through bilateral partnerships under the Global Peace Operations Initiative (GPOI). This program is managed through a partnership between the State and Defense departments. It supports greater performance and accountability among peacekeeping contributors while strengthening bilateral relationships between the U.S. and partner countries. It is both a carrot and a stick, and it is an example of U.S. security assistance that benefits both the U.S. and broader international community.

Women’s Participation in U.N. Peacekeeping

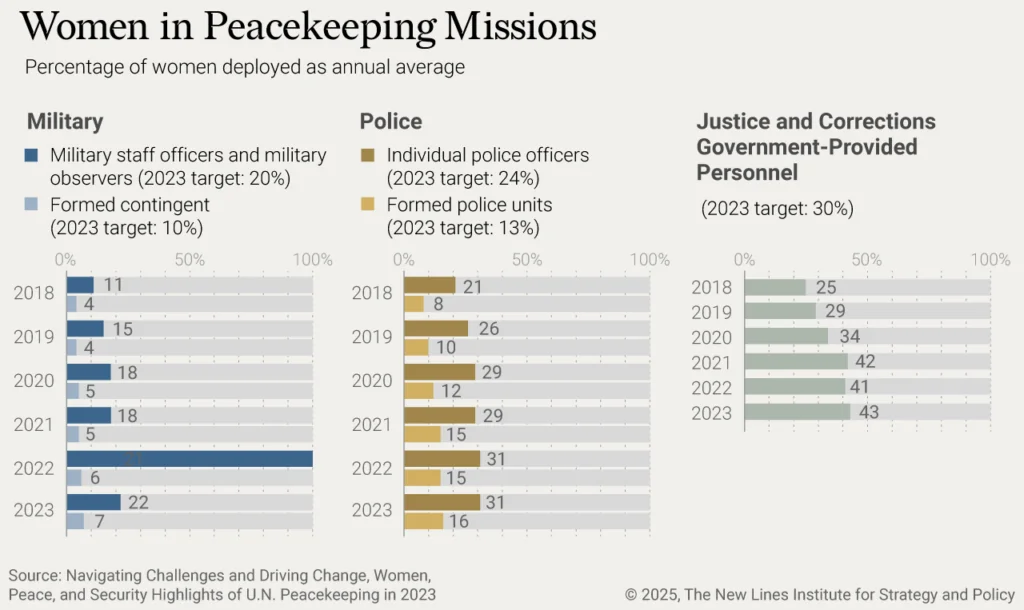

The U.N. acknowledges that increasing women’s participation in U.N. peacekeeping missions improves mission effectiveness by supporting improved early-warning and intelligence collection; greater attunement to the root causes of the conflict and changing conditions on the ground; increased trust and access within the local community; and a better understanding of the power structures within the community and the use of gender-based violence as atactic of war, as well as instances of sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA) perpetrated by peacekeepers against civilians.

Sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA) remain a problem in U.N. peacekeeping operations and constitute a gross violation of human rights. In addition to the obvious examples of SEA, the definition also includes any sexual relationship between U.N. peacekeepers and members of the civilian population because of the power dynamic existing between them. T/PCCs have different cultural contexts and levels of awareness regarding SEA; therefore, the U.N. has integrated raising awareness of SEA into pre-deployment training and has developed a zero tolerance policy for SEA in U.N. peacekeeping. The United States has taken an active role in urging U.N. transparency and accountability around accusations of SEA, at times pushing the U.N. to call for the repatriation of troops following substantiated SEA accusations. Notably, T/PCCs that contribute more female personnel, and countries with better records of gender equality, are both associated with lower levels of SEA.

U.N. peacekeeping missions are accountable for meeting U.N. gender parity targets throughout the mission, in both the military and civilian components, to increase women’s participation in peacekeeping and improve the efficacy of peacekeeping operations. T/PCCs are expected to increase the number of women deployed to U.N. peacekeeping missions, and missions are expected to undertake improvements, such as offering gender-sensitive housing and facilities that make it easier for women to participate in these missions. For many T/PCCs, service in a U.N. mission is a matter of national pride and therefore a coveted opportunity. By promoting women’s service in U.N. missions, the U.N. contributes to the reform of national militaries and provides women around the world with career advancing opportunities and experiences. And by helping partner countries to reach these U.N. standards around gender, the U.S. GPOI program supports better performance and accountability within missions, which serves U.S. interests.

Challenges with U.N. Peacekeeping

Despite the broadly recognized contributions of U.N. peacekeeping to the maintenance of international peace and security, peacekeeping is imperfect, and it is not a panacea. Peacekeeping missions are designed to support the advancement of political solutions, and nearly all are mandated to protect civilians and carry out a variety of tasks aimed at mitigating conflict. But if there is not the political will to reach a solution, peacekeeping missions are often stuck maintaining a status quo that, while arguably better than the alternative, satisfies no one. Political will among the parties and commitment to a genuine peace process are prerequisites for mission success. However, maintaining this commitment from all parties throughout years of conflict is difficult, especially when there are newer, less impartial security alternatives available to support fragile regimes. This places peacekeeping missions in the impossible position of maintaining the consent and cooperation of a host government that wants the mission to concern itself with regime security, while also maintaining the impartiality that is necessary for U.N. credibility as a broker of peace between conflicting parties.

Potential applications of peacekeeping to various challenges, as identified by an independent study on the future of peacekeeping, commissioned by Germany and other U.N. Peacekeeping Ministerial co-chairs ahead of the 2025 summit in Berlin. (Credit: https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/study-on-future-of-peacekeeping-new-models-and-related-capabilities)

The longer that peacekeeping missions remain on the ground without making observable progress or advancing a solution, the harder it is to maintain the consent of the parties and the support of the local population. The mandates for U.N. peacekeeping missions are generally renegotiated by the U.N. Security Council each year so that, in theory, they can respond to changes in the conflict landscape. In practice, these negotiations are affected by broader geopolitical dynamics, and the result is typically a mandate that is not entirely suited to the needs on the ground but represents the lowest common denominator. Political tensions within the Security Council, sometimes driven by divergent objectives within the host country, can lead to fractured support for the mission. This erodes consent and cooperation among host countries seeking to play council members against each other and undermines commitment to a political process.

External factors like widespread disinformation campaigns targeting U.N. missions also affect their credibility and effectiveness. These campaigns are most robust in the areas where Russia and China are expanding their presence – particularly in Africa – and this indicates that the presence of a peacekeeping mission may be viewed as a threat to certain countries’ national objectives. This became abundantly clear in Mali, where the transition government withdrew consent for MINUSMA after welcoming support from Kremlin-backed Wagner paramilitary forces (now operating as Africa Corps), whose pattern of gross human rights violations and exploitation of natural resources did not inhibit the expansion of their popularity as the security provider du jour across Africa, particularly in the Sahel.

Despite these challenges, U.N. peacekeeping missions help to prevent not only the escalation of conflict but also the expansion of security gaps exploited by Russia and others. Through stabilization activities, DDR programs, and a range of community violence reduction projects, peacekeeping missions also create an enabling environment for development and international investment, which reduces opportunities for China to advance its use of debt-trap diplomacy. Therefore, U.S. contributions to the success of U.N. peacekeeping promote global stability, align with national security interests, and counter destabilizing geopolitical trends.

Recent U.S. Policy Toward U.N. Peacekeeping

During the first Trump administration, the United States pushed for peacekeeping reform and actively engaged in the drafting of U.N. Security Council Resolution 2436 on Peacekeeping Performance and Accountability. Then-U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Nikki Haley advocated for clear and achievable peacekeeping mandates and called for a fair distribution of the financial burden required to support peacekeeping. Critics, however, have claimed that her focus on identifying cost savings threatened to hobble U.N. peacekeeping, putting civilians at risk. A heavy focus on cost, rather than adaptation and performance, also signaled a failure to maximize the value of U.N. peacekeeping as a means of robust and holistic U.S. engagement on security issues in Africa.

Under the Biden administration, with the support and leadership of U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Linda Thomas-Greenfield, the U.N. Security Council adopted a landmark resolution opening the door for African Union-led peace operations to be partially funded using U.N.-assessed contributions, and essentially allowing the U.N. to “outsource” peacekeeping to the African Union in contexts where the U.N. does not have the comparative advantage. This was a product of the Biden administration’s policy to simultaneously improve existing tools and expand the international community’s toolkit for responding to conflict. The administration has built on the work of prior administrations to push for improvements to U.N. peace operations and sought to broaden the menu of options available to respond to an array of crises in a variety of contexts. This approach is reflected in the massive U.S. effort to adopt the AU financing resolution and galvanize support for the deployment of the Kenyan-led multinational force in Haiti.

Where Are We Now?

The peacekeeping community is at a pivotal moment in its evolution. A Peacekeeping Ministerial set to occur in May in Berlin will propel discussions on the path forward and result in renewed pledges in support of U.N. peacekeeping. In anticipation of this event, and in recognition of the 10-year anniversary of this biennial summit, the U.N. has commissioned a report on new and existing models of peacekeeping that can be deployed to meet a variety of challenges in an increasingly complex and dynamic security landscape. This is a crucial moment for U.S. leadership to help shape the evolution of U.N. peacekeeping; to advocate for reforms that improve the effectiveness of this important tool; and to ensure that U.N. peacekeeping is equipped to respond to conflict and reduce vulnerability to predatory states and violent extremist organizations.

Conflict and instability are costly, create space for the proliferation of terrorist networks, and cause untold human suffering. Conversely, peace and security create opportunities for the expansion of partnerships, economic development, and global prosperity. U.N. peacekeeping advances U.S. foreign policy goals and responds to concerning geopolitical trends, closing gaps exploited by bad actors. It mitigates conflict, with great benefit to human safety and security. It promotes stability, creating economic opportunity for developed and developing countries alike. U.N. peacekeeping allows the U.S., as a permanent member of the U.N. Security Council, to leverage influence over international interventions that would be impossible – or exceedingly costly – for the U.S. to carry out alone. For all these reasons, it is in the U.S. national interest to invest in the continuous improvement of U.N. peacekeeping, as this is the international community’s most effective tool for responding to threats to peace and security.

Recommendations for U.S. Policymakers

U.N. peacekeeping missions are a service provided by the international community. While some critics refer to U.N. missions as a tool of the West, peacekeeping missions represent the will of the U.N. Security Council to marshal the resources of the international community, the most valuable of which are the lives of peacekeepers from 121 countries, to respond to conflict and contribute to lasting solutions. The incoming U.S. presidential administration has been transparent about its “America first” policy agenda, as well as its skepticism of the United Nations. When it comes to U.N. peacekeeping operations, the United States has an opportunity to rationalize its rhetoric and its policy by reaffirming the U.S. national security benefit derived from these missions through the following lines of effort:

- The United States should pay its peacekeeping bills consistently and limit the expansion of U.S. peacekeeping arrears, which are a result of the current rate of assessment at 28% of the total peacekeeping budget and a congressionally imposed cap on peacekeeping expenditures at 25%.

- Within the Fifth Committee at the U.N. General Assembly, the United States should continue to contribute to realistic and responsible budget negotiations for U.N. peacekeeping operations by identifying areas of inefficiency without undermining policy priorities or jeopardizing operational effectiveness.

- The United States should continue to expand its capacity-building program for troop- and police-contributing countries through the Global Peace Operations Initiative and continue to incorporate performance-enhancing improvements into the design and implementation of training programs for peacekeepers.

- The United States should use the 2025 U.N. Peacekeeping Ministerial in Berlin as an opportunity to reaffirm its commitment to U.N. peacekeeping and advance an affirmative vision for the future of peacekeeping operations, in addition to exploring the potential for African Union-led peace support operations and other non-U.N. models.

- The United States should make substantive pledges at the Berlin Ministerial that align with an affirmative vision for peacekeeping and support the improved efficacy of missions.

- Pledges should include needed equipment, as well as resources to support the ability of U.N. missions to advance a sustainable peace, including financial support for the implementation of the Youth, Peace, and Security and Women, Peace, and Security agendas; the U.N. SEA Victims Trust Fund; and other thematic priorities.

- The United States should leverage its role on the U.N. Security Council, as well as the additional influence it holds over mandates for which it holds the pen, to advocate for realistic and achievable peacekeeping mandates.

This is a pivotal moment in which members of the international community are faced with a false dichotomy between serving the collective good or serving their own national security interests. Challenges with U.N. peacekeeping operations are symptomatic of a broader crisis of confidence in multilateralism, which arises from decades of general abuse of the international system by all parties. Nevertheless, the U.N. remains humanity’s best vehicle for saving succeeding generations from the scourge of war, and U.N. peacekeeping represents the international community’s best effort to respond to the gravest of threats to international peace and security.

Cait Dallaire is a Non-Resident Senior Fellow at the New Lines Institute and an expert on the Youth, Peace, and Security (YPS) and Women, Peace, and Security (WPS) agendas. Prior to joining New Lines, Dallaire served as a foreign affairs officer at the U.S. Department of State, advising on U.N. peacekeeping operations and broader U.N. Security Council issues. Dallaire co-founded the department’s YPS working group and authored the Bureau of International Organizations’ YPS strategic roadmap. Her background includes work on disinformation, climate security, technology-facilitated gender-based violence, and other issues affecting U.N. field missions. Dallaire holds a Master of Science in International Security from East Carolina University and a Bachelor of Arts in International Studies from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of New Lines Institute.