What About the Boys: A Gendered Analysis of the U.S. Withdrawal and Bacha Bazi in Afghanistan

Understanding how the current practice of bacha bazi is linked with the oppression of women’s rights, human rights violations, and pedophilia will be important for the Biden administration as it navigates its new relationship with Afghanistan.

As U.S. troops withdraw from Afghanistan, President Joe Biden must find alternative ways to achieve Washington’s political and strategic goals in the region. The U.S. will likely find ways to engage with Afghanistan outside of the security sector, such as increased diplomacy, economic development, and education assistance. Understanding how the current practice of bacha bazi is linked with the oppression of women’s rights, human rights violations, and pedophilia will be important for the Biden administration as it creates new policy points for the U.S. relationship with Afghanistan. Without an understanding of how these intersecting issues affect Afghan society and policies, U.S. policymakers are missing a key part of the broader picture.

It is also imperative to acknowledge the multifaceted gendered dynamics impacting Afghan society that lead to support, both openly and tacitly, of the Taliban in certain regions. The predatory and abusive nature of some men in the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) and the lack of concern on behalf of the U.S. military continues to undermine public support for the U.S.-Afghan partnership in both countries. This is especially at a moment when the Afghan government needs U.S. funding to try and maintain a semblance of stability.

Turning a Blind Eye

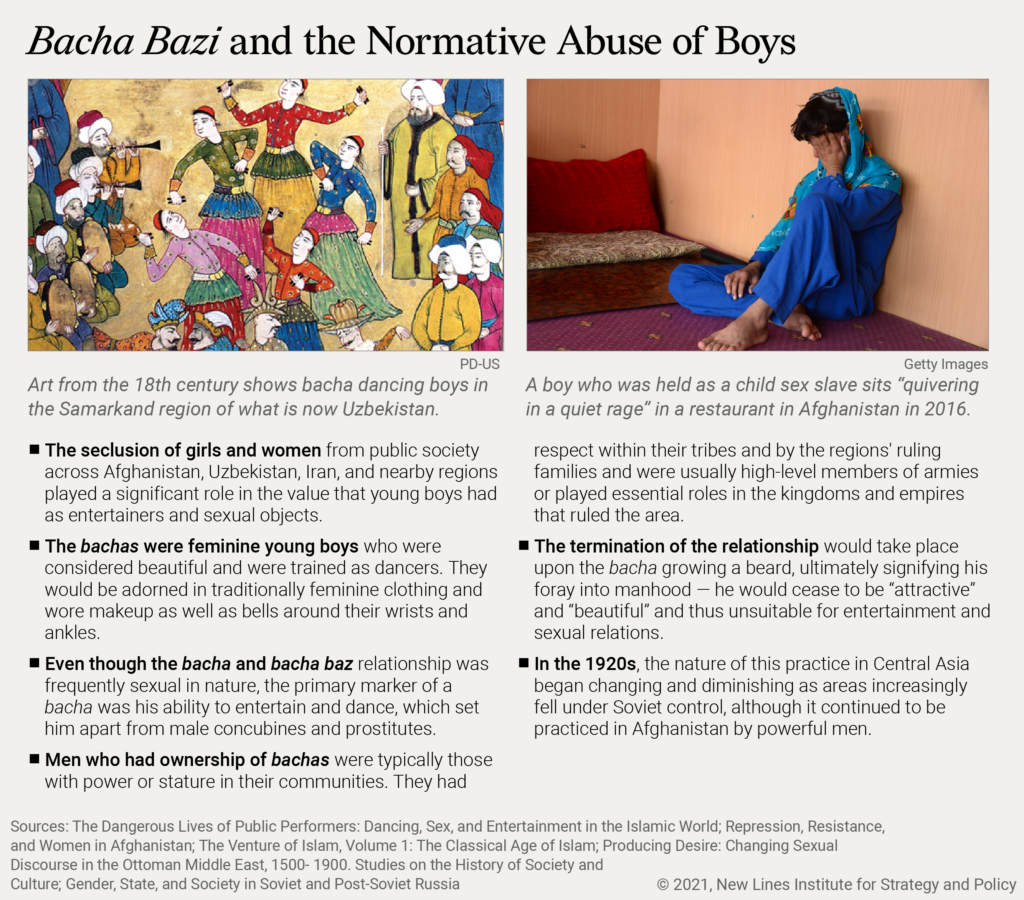

Bacha bazi is a term found in multiple languages and translates roughly into English as “boy play.” While the name takes on different meanings and conjures different understandings throughout history, at its foundation bacha bazi involves pre-pubescent boys dancing for and entertaining a group of men, typically during large gatherings such as weddings. The historical practice of bacha bazi is much more nuanced than its current iteration of sexual abuse of young boys, and it is important to understand the role it plays in today’s Afghanistan, including as a key factor in the rise of the Taliban, who have been public in their opposition to the practice.

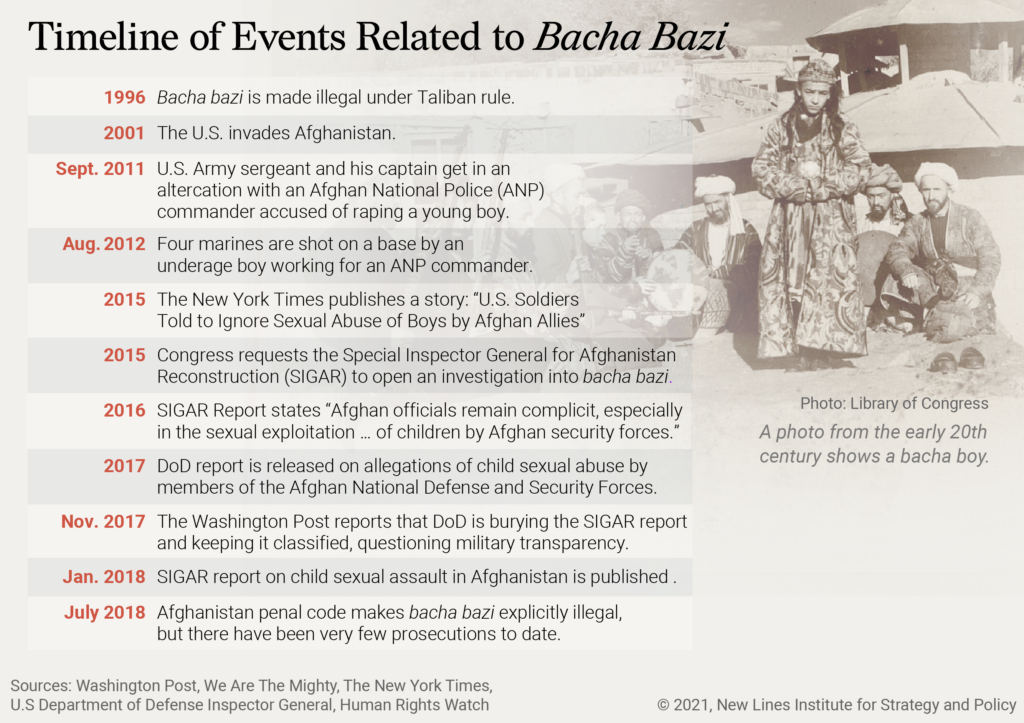

In the past, transgenerational same-sex sexual relationships between the dancing boys (the bachas) and older men (the bacha baz) were common alongside the entertainment the boys provided in social settings. The Taliban banned and publicly punished the practice when they came to power in the 1990s, but after the collapse of their regime in 2001, when the former Islamist commanders from the days of the anti-Soviet insurgency came to power, bacha bazi again became common in certain regions of Afghanistan and evolved into boys being kidnapped, trafficked, and raped without any semblance to or recognition of the cultural nuances that used to embody the practice such as dancing at events or social gatherings. In today’s Afghanistan, it has become an avenue for wealthy or powerful men, particularly those involved in the factions that were part of the former Northern Alliance and the ANSF – the U.S. allies in the region – to sexually abuse young boys under the pretense of engaging in the historical practice of bacha bazi.

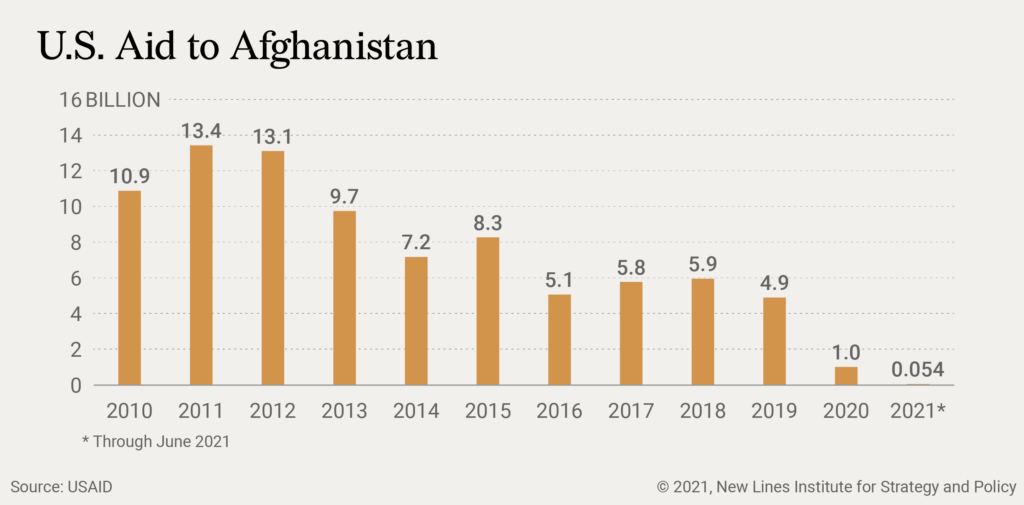

The United States has long known about the prevalence of bacha bazi among its partners in the ANSF. It is clear that the U.S. Department of Defense was aware, by 2009 at the latest, of coercive relationships between men and boys on U.S. military bases in Afghanistan. Billions of dollars were spent in order to ensure that the partnership between U.S. forces and ANSF had sufficient capacity to manage and maintain the internal security throughout Afghanistan. In the development of a security sector assistance plan, the U.S. overlooked multiple instances of criminal activity and gross human rights violations, including the sexual abuse of children on military bases.

The rampant nature of bacha bazi in some regions risked the legitimacy of the Afghan government in the eyes of Afghan civilians and undermines Washington’s reputation and that of America’s multilateral international partners. This will have long-term impacts well after the United States has completed its troop drawdown. Over the decades of the American military presence in Afghanistan, the U.S. has continuously turned a blind eye to the ANSF’s and Northern Alliance’s insistence that the current iteration of bacha bazi is Afghan culture, when in reality these groups are co-opting a historical practice in order to traffic and sexually abuse vulnerable Afghan boys. The continued and unquestioned support of the ANSF puts at risk long-term goals for stability and peace in Afghanistan, which the U.S. should continue to emphasize through foreign aid.

The ANSF have been one of the most critical partners in the U.S. fight against the Taliban and in international efforts to stabilize the country. According to the 2015 Congressional request to investigate these potential human rights abuses by a vital security partner, there was concern that any behaviors exhibited, and actions taken, on a U.S. military base would considerably harm reconstruction and stabilization efforts.

Ignoring human rights violations in favor of assumed strategic benefits and security, however, has costs. Justice and human rights should not be secondary concerns in Afghanistan as they are fundamental to its stability. The inextricable linkage between human rights and stability is readily apparent when one considers that the Taliban have used bacha bazi as a recruiting tactic and as a way to bait the ANSF into further violence. However, it has become clear that American dollars are critical to the war in Afghanistan and the U.S. should prioritize long-term funding to the country, especially considering that grants continue to finance about 75% of Afghanistan’s public spending.

This raises the question: Is the U.S. funding bacha bazi directly or indirectly, and should the U.S. continue protecting, training, and financially supporting the ANSF given its history of known human rights abuses? The U.S. spent $978 billion on the war from 2001 to 2019, but despite a growing awareness of sexual abuse on U.S. military bases, little to nothing was done to curb funding or sexual violence. It is clear that boys need to be more actively discussed as an integral part of any human rights agenda in Afghanistan, where women and girls are given an almost exclusive focus. The U.S. failed to protect Afghan boys from abuse by its allies in the government and security forces, and the Taliban have used this to their strategic advantage.

If the U.S. plans to continue its support and funding of Afghan security forces and the Afghan government, there needs to be a consistent effort to minimize human rights abuses, including bacha bazi, by the ANSF to counter the Taliban narrative that protecting boys from bacha bazi led to their increased influence in the late 1990s. By ensuring that U.S. security partners are working within the confines of international law and abiding by the Afghan penal code, the U.S. can facilitate the ANSF to build trust around the country. Moving forward, the U.S. must decide where it will draw the line when valuable security partnerships are actively participating in serious crimes and human rights violations against the very people they are supposed to protect.

As U.S. troops withdraw, the Taliban’s outsized role in the country’s future is becoming increasingly apparent. The Taliban’s disdain for the U.S. focus on “women’s rights” has been clear; last year, leader Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar said explicitly, “The only work done under the shadow of occupation, in the name of women’s rights, is the promotion of immorality and anti-Islamic culture.” What is less clear is how the Taliban’s political presence will impact young boys. The U.S. has consistently been vocal on protecting women and girls in their statements and policies on human rights in Afghanistan, leaving the threat of bacha bazi and the unique gendered violence faced by young boys underexplored and misunderstood.

Statements have been an important tool in rallying support for the ongoing U.S. presence in Afghanistan. They have the potential to turn into real policy initiatives to help Afghan girls, especially with access to education, but the U.S. should similarly signal its support of young boys who have also been uniquely harmed, due to their gender, by conflict in Afghanistan. The U.S. has long cited “freedom of women” as a reason for fighting the Taliban and staying in Afghanistan. Irrespective of the actual reasons, there has been a continuous American presence in the country since 2001, and women’s rights have consistently remained a talking point for American support of the war. However, the U.S. must recognize that the practice of bacha bazi is fundamentally detrimental to women’s rights because it reinforces traditional gender norms and the infamous idea that “women are for children, boys are for pleasure” in Afghanistan.

Bacha Bazi and the Taliban

Bacha bazi played an important role in the rise of the Taliban. As the war against the Soviets came to an end, the Islamist insurgents had power, money, weapons, and a fractured idea of what the future of Afghanistan should look like after the war. In the ensuing civil war, these factions were able to act with considerable latitude in many parts of the country because they drove out the Soviet Union, which had tried and failed to implement unpopular economic and social reforms.

One thing that remained consistent during these conflicts is reports of bacha bazi or “chai boys” among the Islamist insurgent commanders. When Soviet forces entered the country and the Islamist insurgencys began, rebel fighters began disregarding certain cultural and social norms in Afghanistan. Reports of bacha bazi grew, becoming less about the historically centered entertainment and more about abuse and sexual slavery. In the later insurgency years, more and more fighters would kidnap young boys and keep them at their military camps, nominally as porters or “chai boys” but in reality almost always sexual slaves to multiple men as a way to further project those men’s power and status. The public and aggressive nature in which militia commanders participated in pederasty in their communities, even though the practice was reviled by large portions of the population, is credited as one of the reasons for the growth and popularity of the Taliban. During the insurgency, Kandahar’s Pashtuns would say, “When crows fly over Kandahar they clamp, one wing over their bottoms, just in case.”

The public nature of this abuse led to an increase in local support for the Taliban when the group’s founder, Mullah Omar, rescued a young boy who was going to be sodomized by two militia commanders. The Taliban began saving more young boys and resolving local disputes and, through this, tried to set themselves apart from those who participated in bacha bazi or pederasty in any capacity. However, after the U.S. invaded in 2001 and toppled the Taliban regime, there was a reported surge of bacha bazi, especially in Pashtun-majority regions but also throughout the country. One local said, “They say birds flew with both wings with the Taliban, but not anymore.”

As we approach the departure of U.S. forces from the country there has been significant focus on what it will mean for women and girls, and rightfully so considering what life was like for them under the Taliban. However, by forgetting the important position boys play in Afghan society and in the lore around the Taliban as the self-styled arbiters of Islamic ideals and religious moral standing, policymakers are missing a critical component, which will catalyze conflict in a post-American Afghanistan.

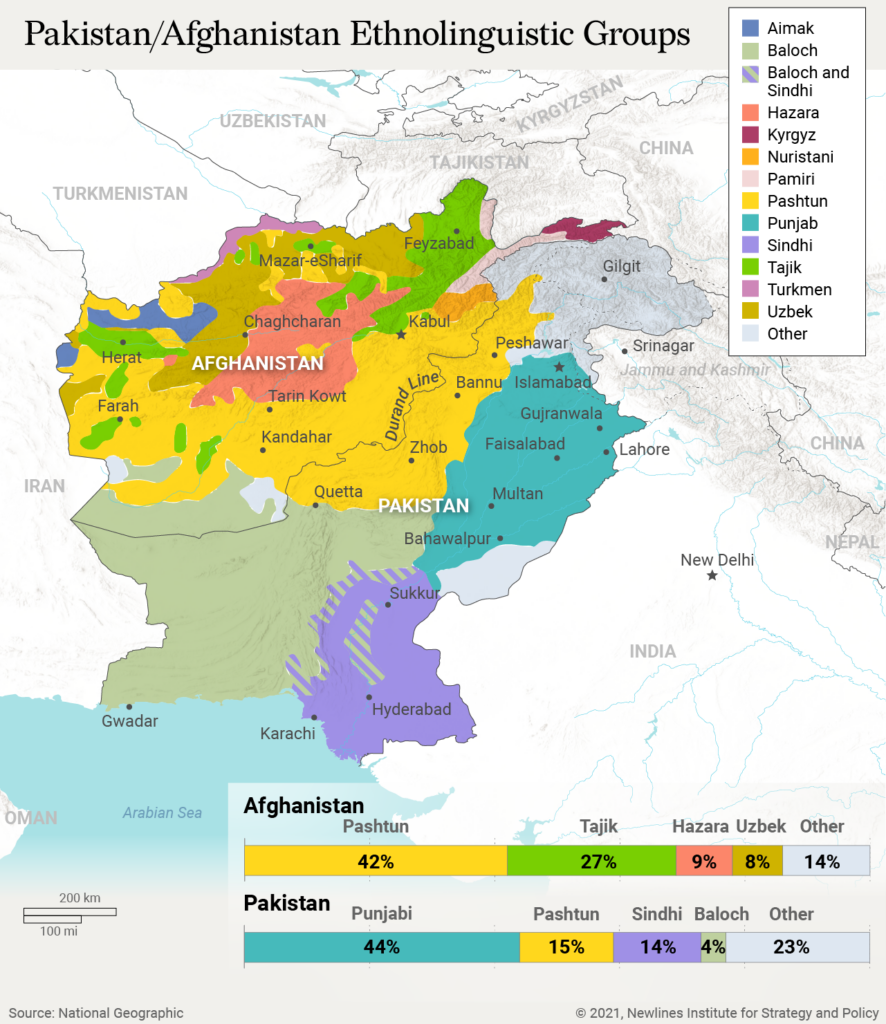

The Gendered Dimensions of Afghanistan

Western accounts of gender in the southwest Asian country frequently stipulate the sequestration of genders as “female seclusion” when in reality the men are kept outside as much as the women are kept inside. Throughout Afghanistan, the movement of women was severely constricted across all ethnicities and cultures such as the Hazara, Uzbek, and Tajik societies; however, none are as limiting of women’s movements as the Pashtuns who make up the country’s ethnic majority. The extreme level of seclusion among Pashtuns could point to why the practice of bacha bazi is more prominent in Pashtun societies. Though the prevalence is difficult to discern due to limited data available, it has been suggested that approximately 50% of men in Kandahar had some iteration of sexual intercourse with men or boys at some point in their lives. However, it is important to note that this is not a regional or ethnic phenomenon and occurs in various provinces around Afghanistan.

While conservative interpretations of the Islamic texts do play a role in the gendered frameworks of modern-day Afghan society, historically it is primarily the cultural and tribal foundations that shape the masculine and feminine identities and expectations in Afghanistan. Western understandings of homosexuality do not align with men who have sex with men in Afghanistan, which is significantly dissimilar from gay male identities in the West. Men who participate in bacha bazi often openly flaunt their bachas as a status symbol. The sexual nature of the relationship between the man in power and the boy who is being abused is such that the older, dominant male is almost always the penetrator (dominant and active) and the young boy is the penetrated (submissive and inactive) party. Thus, the man can still be viewed as a dominant male within the Afghan framework of a masculine identity because anally penetrating other men, and in particular young boys, is not seen as an act of homosexuality and is not emasculating, leaving the penetrator’s masculinity and honor intact. In Afghanistan, homosexuality is forbidden and, under tribal customs, punishable by death, but that does not necessarily mean one should assume it does not happen. What is too often missed in Western analysis is that individual sex acts or behaviors do not necessarily define one’s sexual orientation in Afghanistan.

It is important to understand that more generalized child sexual exploitation should not be conflated with the historical practice, and past iterations, of bacha bazi. This allows for perpetrators of these crimes to hide behind the claim that what is happening to boys in Afghanistan today is “culture” when in fact it is driven primarily by human trafficking and kidnapping. According to the most recent U.S. Department of State Trafficking Persons Report, young boys are the most vulnerable to human trafficking in Afghanistan — specifically boys aged 13 and under, for their participation in bacha bazi and other forms of sexual abuse. In Kandahar province in particular, community elders and local police openly traffic and exploit boys in bacha bazi without fear of reprisal. Prosecution is incredibly rare; only in the past year have powerful men been held to account for their actions. It is imperative that the U.S. continues to encourage and assist with legal reforms that allow for increased prosecution of the existing laws around bacha bazi.

Policy Recommendations

As the U.S. looks for new policy points to continue its relationship and support to Afghanistan, Afghan boys must be a part of these discussions. One of the clearest ways the Biden administration can do this is by withdrawing the notwithstanding clause, which allows for the U.S. Defense Department to continue to fund the ANSF irrespective of any human rights violations that might fall under the scope of the Leahy Amendment. This clause has been used repeatedly by the department and the U.S. government in order to avoid cutting off military aid to Afghan units the U.S. military has deemed necessary for its security objectives or critical to filling security gaps.

If the U.S. will not utilize the Leahy Amendment in Afghanistan due to its strategic partnership of the ANSF or the costs associated with vetting, it should mandate reporting of human trafficking and child recruitment by the ANSF at the bare minimum. According to the Department of State 2020 TIP Report, recruitment and use of child soldiers remains underreported and is a frequent way that the ANSF gets access to young boys. By continuing to fund the ANSF without regard for their human rights track record, the U.S. is turning a blind eye to the mass sexual abuse of young boys by its security partners.

As the U.S. government continues to invest in Afghanistan post-troop drawdown, maintaining funding through Title 22 and the Defense Department is necessary to maintain transparency. Directing support for Afghan troops through the Intelligence Community (IC) will only exacerbate human rights abuses, particularly towards young boys in the country. Intelligence funding in Afghanistan has led to catch and kill operations that have left young boys executed in the middle of the night. Continued funding to Afghanistan and U.S. security partners in the region will be vital for the future of Afghanistan. It is inevitable that funding will be funneled through the IC, but this funding should come with required reporting to the Special Intelligence Committee on IC funded programs in the country in order to mitigate incidences like the 2019 Madrassa Killings.

The Biden administration must also crack down on the use of private contractors that fall outside the scope of the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ) and thus have more purview to commit human rights abuses. As U.S. and NATO troops withdraw, defense contractors, who make up America’s largest force in Afghanistan, are not only staying but also increasing their presence by hiring more contractors. At the moment, the Defense Department employs over 16,000 contractors in Afghanistan, 6,147 of whom are U.S. citizens. Since 2002, the Pentagon has spent $107.9 billion (nearly 11% of total spending) on contracted services in Afghanistan.

While U.S. military members are held to the UCMJ, defense contractors exist in a gray zone where they are not held to the same, or any, human rights standards. There have been reports of U.S. defense contractors in Afghanistan engaging in bacha bazi in the past. As U.S. and NATO troops leave, there is an increased probability of human rights abuses since the U.S. is leaving both American and foreign contractors (both paid by the U.S.) with little to no oversight or accountability. The last thing the U.S. needs is another scandal relating to its military operations abroad, so the Biden administration should be very careful in how it deals with contractors after September.

It is imperative that the U.S. government and the Biden administration take the welfare of young boys seriously as they move into the next phase of engagement with the Afghan government. America’s focus on girls’ education and women’s rights is acceptable only if it is paired with equal concern for the boys that experience extensive sexual abuse from men in power.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not an official policy or position of New Lines Institute.