Why Are Refugees Returning to Ukraine?

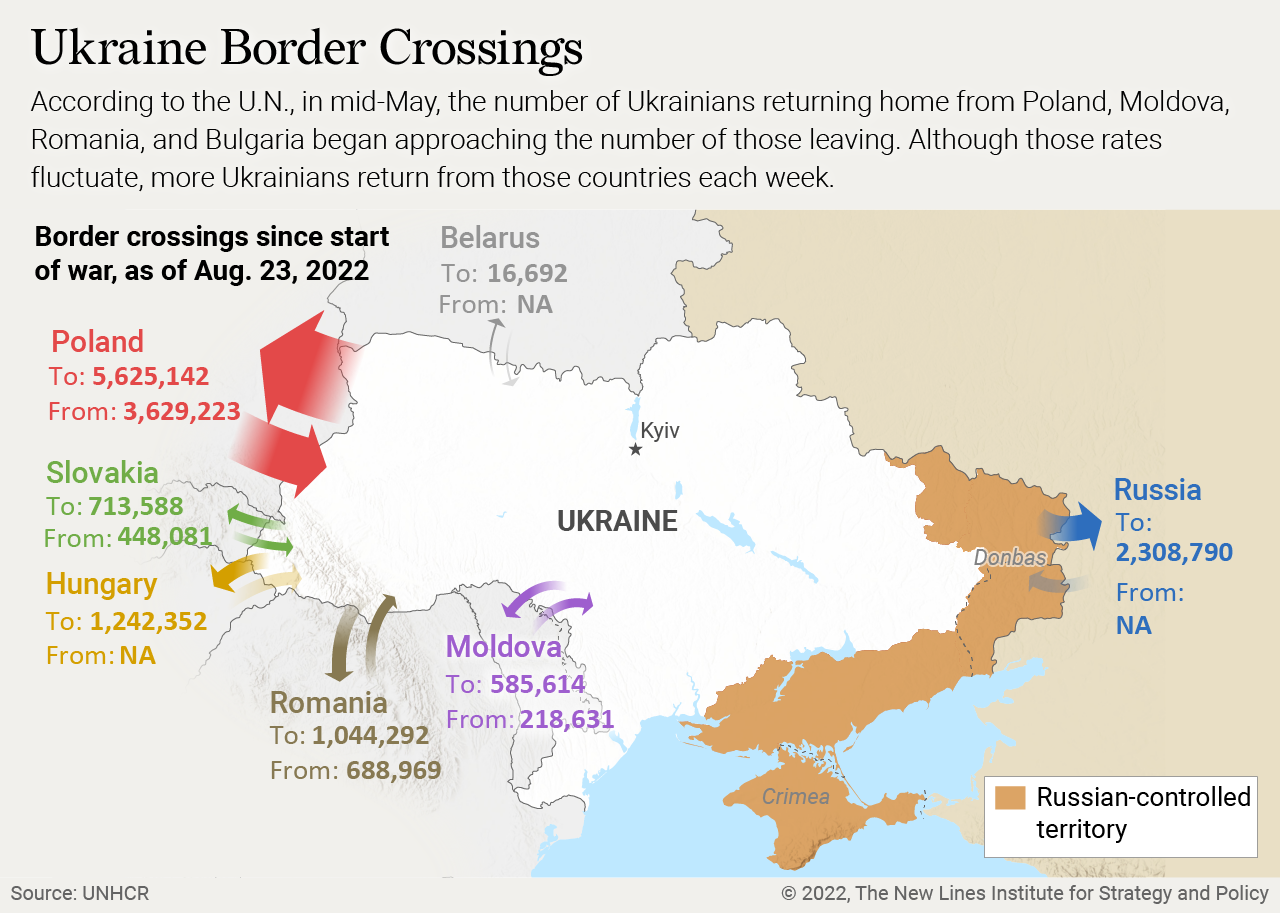

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine began on Feb. 24, the U.N. Refugee Agency (UNHCR) has recorded more than 10 million border crossings from Ukraine into neighboring countries. However, recent border-crossing data has shown a steady increase of refugees back into the war-torn country, currently totaling 3 million. The trend represents concerning evidence that many Ukrainians would rather live in danger inside Ukraine than live the uncertain life of a refugee. However, premature repatriation poses a human security risk to Ukrainian refugees and must be addressed by the countries hosting refugees as well as the United States.

Some refugees return for short-term reasons, like assessing the situation, checking on property, or visiting family members or helping them leave, but others intend to stay permanently. The UNHCR notes that many who have returned to Ukraine have found their property severely damaged and struggled to find jobs due to the war’s continued devastating economic impact, and thus have had no choice but to leave again. According to an initial survey done by UNHCR, of the refugees returning home, 84 percent were intending to return to their place of origin.

While refugees are returning to western oblasts that have a higher level of perceived safety, many are using them as a transit point to travel onward to central, northern, and eastern oblasts. Most refugees returning home aresettling in central oblasts like Kyiv. Data from the U.N.’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs reveals that refugees are also returning to oblasts in Eastern Ukraine like Kharkiv, where local officials in mid-May reported that an average of 2,000 refugees per day have returned. More than half of Ukrainians who left the country were residents of Ukraine’s east and south, and 45 percent came from central regions, including 31 percent from the Kyiv region.

When conditions for return remain objectively too uncertain to ensure safety, it is UNHCR’s stated responsibility to provide guidance and make its position known. The dangers of returning home too soon should be addressed by the countries hosting refugees and the United States. The U.S. and Europe must focus their energy and resources on making it easier for the refugee population – made up of primarily women, children, and the elderly – to stay in host countries and integrate into the local community. For its part, the U.S. needs to incorporate refugee relief beyond immediate humanitarian concerns as part of its broader aid package to Ukraine.

Why Are Refugees Returning?

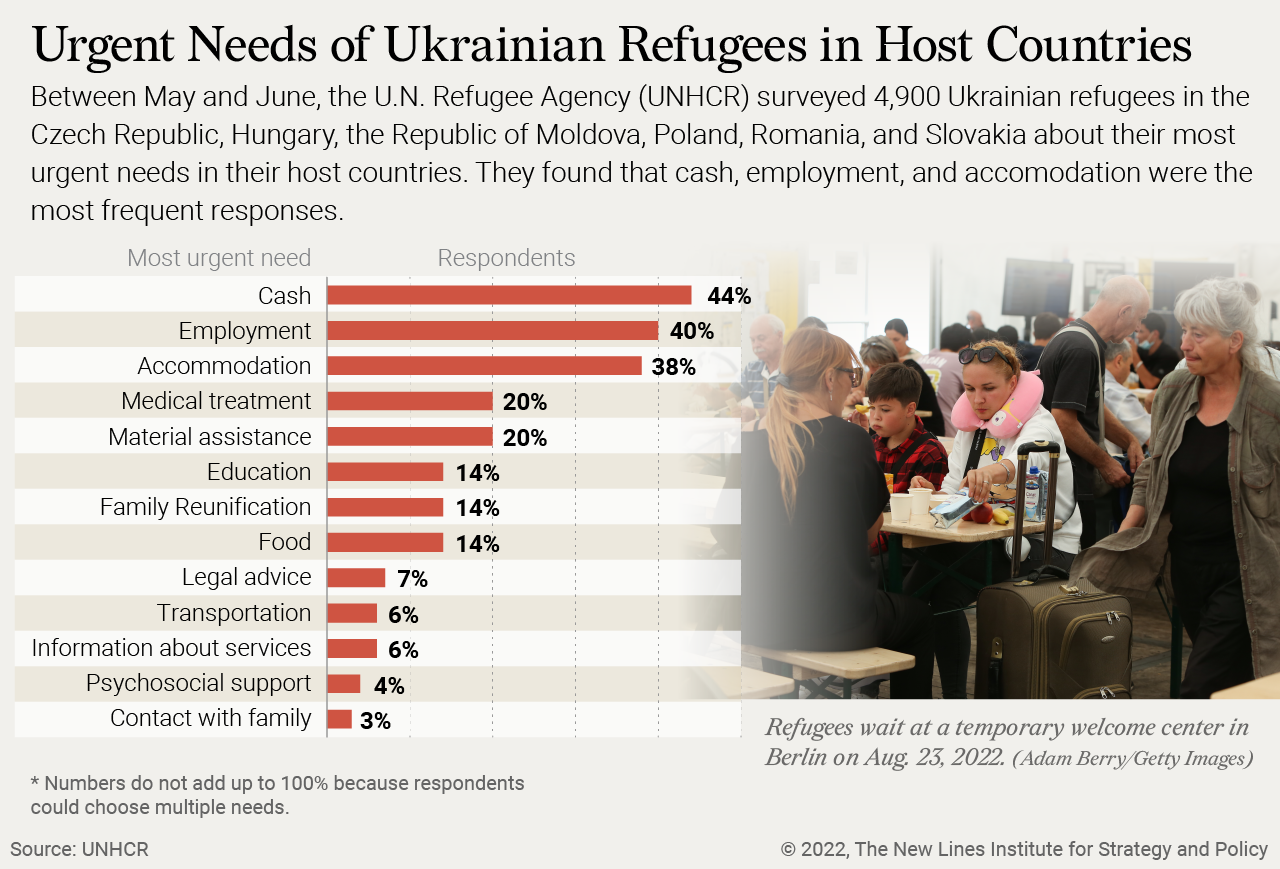

Lack of Proper Infrastructure in Host Countries

The surge of refugees returning reflects the challenges European host countries have faced in providing for Ukrainians during the continent’s largest refugee crisis since World War II. More than 70 percent of those returning were in Poland; some see this movement as a positive step for easing pressure on a country that has struggled to supply housing for Ukrainian refugees. The surge in housing demand pushed up rents in Warsaw by more than 40 percent compared to a year ago. The insufficient supply led to office buildings being converted into dormitories. The number of refugees returning is increasing, despite continued fighting in Ukraine, indicating that host countries have fallen short in terms of proper infrastructure to meet refugee needs.

Bulgaria provides a key example of the failure of government to meet Ukrainian refugees’ housing demands. More than 110,000 refugees were being housed in private hotels in seaside resorts until the government abruptly terminated the program on May 31 in anticipation of the tourist season, leaving these refugees in limbo. This uncertainty regarding their housing prompted many Ukrainians to leave, either to return to Ukraine or seek housing in other host countries. Due to this disorganized internal response and poor public messaging, refugees lacked sufficient relocation support from the European Union and left to seek housing in neighboring Romania.

Aside from housing, host countries are also not providing adequate child and employment support. Given that the refugee population is largely made up of women and children, host countries must provide accessible childcare to single mothers before they are able to seek full-time employment to support themselves. A refugee who traveled to both Poland and the Czech Republic told The New York Times that she returned to Ukraine with her son primarily due to a lack of employment opportunities. The only job available to her, given that she couldn’t speak the local language, was house cleaning, which did not pay enough to support her and her son’s expenses, like housing.

The effect of rising inflation and the economic fallout that occurred in the aftermath of Russia’s invasion may be affecting host countries’ capacity levels and refugees’ ability to find work. Supply shocks and continued sanctions pose inflationary risks to the global economy, all while countries confront a refugee crisis, food insecurity exacerbated by the war, climate change, and the ongoing consequences of a multiyear pandemic.

Perceived Safety of Return

When refugees began returning in large numbers in mid-April following the liberation of Kyiv, the governor of the Kyiv region, Oleksandr Pavlyuk, advised them it was safer to remain abroad. For many of the refugees returning to western oblasts like Lviv and Vinnytsia, the primary reason is perceived safety of return. At this stage, the war is highly concentrated in the eastern and southern parts of Ukraine, making the west a relatively safe haven for many Ukrainians, although these regions still are vulnerable to occasional Russian missile attacks . However, these oblasts took in more than 2.5 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) during the initial phases of the war. Having many refugees return puts a strain on already limited resources like food and housing, threatening to displace these IDPs for a second or third time in their search for safety.

According to the International Organization for Migration’s latest assessment in late May, current IDPs’ readiness for further mobility has remained high since their assessment in mid-April. Among IDPs in the West, 52 percent intend to move farther in any direction, including possible return, as do 48 percent of IDPs in the Center macro region, 44 percent of IDPs in the North, and 31 percent in the South.

Single mothers and children could choose to return to Ukraine because they will have a strong support network of family and friends in Ukraine, shared language, and fewer risks related to gender-based violence and human trafficking. Given the strain that host communities are facing in terms of housing and resources, the UNHCR is not adequately discouraging refugees from returning to Ukraine despite the pertinent human security risk it poses to themselves and others.

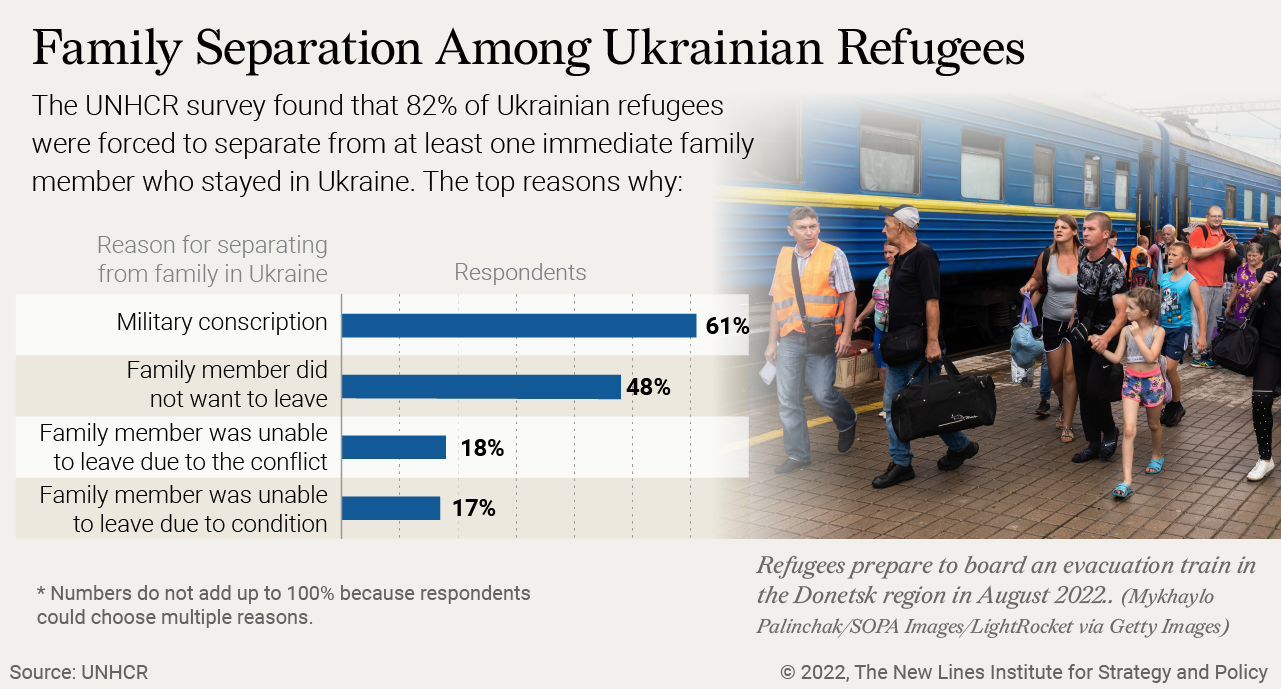

Family Reunification

Most crossing the border back into Ukraine are women and young children, as men over 18 were not permitted to leave the country due to martial law. Reunification with male, elderly, or sick family members who were unable to make the journey was the primary reason for Ukrainians’ return to more dangerous oblasts in Eastern Ukraine. where the fighting is still occurring. When asked about the risk of danger, many Ukrainians said they would rather be with their families, as the war could last for years, and believe that facing danger at home is better than life as a refugee.

The temporary protection directive that took effect following the invasion of Ukraine allows Ukrainians to travel among the Schengen-area countries only for 90 days. Once that time period is up, they must stay in the country they are in, or they lose their protection. Because of this inflexible approach to freedom of movement, families could be spread across multiple European countries, resulting in Ukrainians choosing to return to Ukraine where they can all be together in one place.

Solutions to Premature Repatriation

European host countries can take several steps to mitigate the risk of premature repatriation of refugees. Most importantly, countries need to ensure there is adequate programming to assist refugees in finding housing, employment, and childcare. A lack of guidance in these processes can leave refugees feeling hopeless and more willing to return to their countries of origin. In addition, other services like language learning, mental health services, and women’s empowerment programs would be instrumental in ensuring refugees are better adjusted to their new communities. All these support systems should be in place and activated within the first 90 days of refugees arriving, as this is when they need the most support and are more vulnerable to premature repatriation.

Secondly, the European Union should formulate a more flexible policy in terms of family reunification. Under the current temporary protection directive, leaving a host country to reunite with family is only acceptable within the first 90 days after arrival. This does not consider family members who may have been separated during the war and unable to get in touch with each other, or families that left Ukraine at varying times and went through different transit points on their passage into European host countries. Having a more flexible policy for family reunification would allow refugees to remain protected in their current country if they help or find a family member.

Lastly, while the fighting persists and conditions in Ukraine remain unstable, countries should make their positions on premature repatriation known. This can be done through stronger public messaging about the potential dangers of returning to Ukraine before the war is over. It is the UNHCR’s stated responsibility to provide guidance and advise against premature repatriation in unsafe circumstances. Coordinated campaigns between UNHCR and host countries that promote safety, community, and well-being should be instituted to ensure the collective human security of all refugees.

Lessons from Europe for the United States

The United States should learn from the experience of European host countries when addressing refugee crises moving forward. In May, Congress approved the Additional Ukraine Supplemental Appropriations Act, which allocated nearly $5 billion in humanitarian assistance funding for Ukraine and neighboring countries. The bill also authorizes citizens or nationals of Ukraine who come to the United States with humanitarian parole under the Uniting for Ukraine program to be eligible for limited resettlement benefits. These were important measures to support refugees; however, the United States can do more to ensure better integration of refugees in the first 90 days.

Since the United States is accepting Ukrainian refugees through an ad-hoc channel run by the Department of Homeland Security and known as humanitarian parole and not through the standard U.S. Refugee Admissions Program, refugees are not guaranteed special status. This means there is no funding for Ukrainian parolees to receive the type of important support in their first 90 days that is afforded to other refugees. For example, while Ukrainian parolees are allowed to work in the United States, they must apply for work authorization first, a process that generally takes five to seven months, meaning they will have no income until they are approved.

USAID and its partners, International Organization for Migration, UNHCR, and UNICEF have been instrumental in providing protection and legal services to vulnerable individuals in Ukraine and neighboring countries. They have established Blue Dots, multiagency facilities that provide one-stop protection services like prevention of and response to gender-based violence and human trafficking, and social service referrals to new refugee arrivals in neighboring countries. These services have reached tens of thousands of people in Bulgaria, Hungary, Italy, Moldova, Poland, Romania, and Slovakia. USAID should continue the establishment of these services for refugees in the United States in order to facilitate child and woman-friendly spaces to ensure refugees feel physically and emotionally safe upon arrival. In order to apply the lessons learned from these foreign activities, U.S. Congress should refine and fund monitoring and evaluation programs like Blue Dots to ensure safe and effective refugee absorption.

The funds Congress authorized that go toward longer-term integration support are necessary, but the immediate needs Ukrainian parolees may have upon arrival in the United States must be addressed in order to avoid premature repatriation. Without addressing the immediate needs of refugees, the government places the primary responsibility of ensuring the well-being of arrivals on the support of community members. In places where this support falls short or does not exist, Ukrainian parolees do not have a strong foundation for life in the United States.

While supporting refugees does generate immediate expenses, they should be seen as short-term investments. When host countries support integration efforts, refugees are more likely to contribute to new economic activity that will eventually offset the immediate costs. As Israeli economist Danny Bahar notes, refugees provide economies with new skills, start businesses at higher rates than locals (thus creating more jobs), and forge international connections that promote trade and foreign investment. All of this contributes to growth of gross domestic product, but only if host countries are willing to invest in policies that support economic and social integration. These efforts can and should be balanced with measures that support Ukraine’s own economic activity when it is relatively safe for refugees to return. The education and training that young Ukrainian refugees receive in the European Union and the United States can be applied to Ukraine’s own development when it is safe and desirable for refugees to return. Thus, these integration efforts are not only short-term investments for host countries, but also long-term investments for Ukraine and the West at large.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of the New Lines Institute.