As Ukrainian Refugees Arrive, the EU’s Public Health Crisis Grows

Listen to article

In what has been deemed the largest displacement crisis in Europe, 7.1 million Ukrainians are internally displaced, and more than 4.7 million are seeking refuge in nearby countries after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The impact of sudden displacement has had undeniable consequences on the well-being of Ukrainians of all ages, leading to an increased prevalence of common mental health conditions, such as post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety. With over 1.1 million Ukrainian refugee arrivals in neighboring Poland alone, there are urgent implications for the scale-up of national health systems in countries across the European Union to support the mental health of newly displaced persons as well as facilitate their social integration.

Lessons from past displacement crises indicate that a lack of investment in the scale-up and dissemination of mental health services for displaced populations can impact their short- and long-term integration in host country contexts. Protracted bureaucratic processes and lack of certainty regarding legal pathways for asylum, as well as discriminatory rhetoric and social exclusion, can also exacerbate the effect of trauma experienced throughout the migration journey and can have significant consequences on individual well-being and integration.

Since February 2022, the U.S. has provided $914 million in humanitarian assistance to displaced individuals in Ukraine and abroad as a result of the Russian invasion. European host country governments and their health ministries have been at the forefront of coordinating the public health response for recent arrivals. These actors who have rolled out assistance and policies for displaced Ukrainians should learn and adapt from the resettlement and integration of pre-existing refugee communities in Europe, such as Syrians and Afghans. The mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS) needs of recently displaced Ukrainians are a priority, and the renewed attention on refugees in Europe should catalyze improvements for the ongoing needs of refugees displaced previously to Europe and other host countries.

Policy proposals that the U.S. can engage with to promote better public and mental health service access for displaced Ukrainians include explicitly earmarking funds for MHPSS initiatives within existing and future provisions from agencies like USAID and the State Department’s Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration. This extends to funding provided to groups such as the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and the U.N. Refugee Agency (UNHCR), which focus on building local capacity to provide MHPSS services in displacement contexts as well as advocating for the integration of both existing and newly displaced populations into national health systems.

Refugee Mental Health Needs

The devastating impacts of the recent invasion echo previous traumas Ukrainians experienced during decades of turmoil with Russia and armed conflict in the eastern parts of the country. According to the World Health Organization, before the current conflict, mental health was one of the leading causes of disability in Ukraine and affected about 30% of the population. Despite these needs, investment in the national mental health system was minimal, comprising only 2.5% of the national health budget.

Claire Whitney, the senior global MHPSS advisor with the International Medical Corps, which has been operating in Ukraine since 2014, spoke about further access barriers which contributed to large treatment gaps in the country: “The mental health care system [in Ukraine] is very highly centralized and medicalized, and therefore for those that do need any kind of psychiatric treatment, they need to be in a city to access a psychiatric hospital. … Having that kind of mental health care available at the community level is still a big gap.”

For recently displaced Ukrainians, pre-existing mental health conditions may be exacerbated by grief, chronic stress, and high levels of anxiety experienced throughout the migration process and due to the uncertainty of their situation and that of their loved ones. These symptoms might also vary depending on which part of Ukraine individuals are being displaced from and the scale or severity of conflict they witnessed before their displacement. For example, women who may have experienced sexual violence by Russian soldiers are at particularly high risk and require immediate care. Other at-risk groups include the elderly, who make up a significant portion of the Ukrainian population, and other vulnerable populations at high risk of mental health conditions, including those who were previously displaced internally within Ukraine.

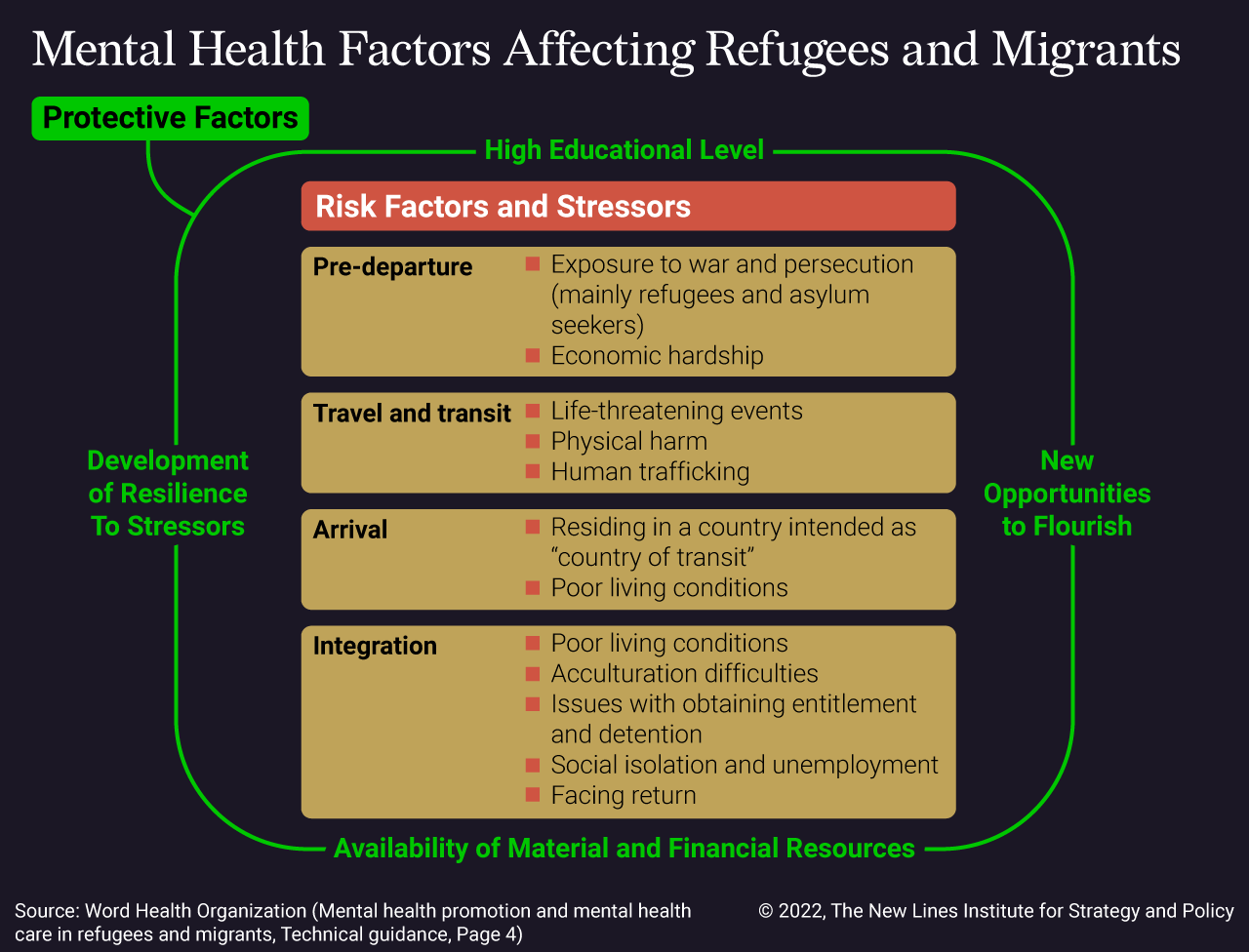

Information regarding other displacement events shows that in comparison to the host country population, individuals who experience forced displacement report a higher prevalence of mental health conditions. For example, among a random sample of Syrian refugees who arrived in Sweden between 2011 and 2013, 40% met the criteria for depression and close to 30% for PTSD. These trends are consistent with previous research on the prevalence of mental health conditions among refugees, which indicate that refugees resettled in Western countries are about 10 times more likely to have PTSD than members of the host population at similar ages. Poor mental health outcomes can be a result of a variety of risk factors and stressors experienced throughout the migration journey.

Once registered, refugees in Europe generally have access to public health systems in their respective host countries. However, there is significant heterogeneity and demonstrable inequalities in health service utilization among refugees across various countries within the EU. Specific obstacles when accessing mental health services include language barriers that prevent the individual from initiating the process to seek help from a mental health professional or adequately being able to express their needs or feel understood when they do access care. Financial insecurity or uncertainty also pose a challenge for refugees and asylum-seekers wishing to seek mental health treatment due to potential costs of transportation, services, or medication. Other barriers include fear of showing vulnerability, and as a result, being persecuted by host country authorities or forced to return to their country of origin.

These barriers also apply to recently displaced Ukrainians, who may not seek out mental health services on their own upon arrival in their host country. Results from a 2016 nationwide survey of 2,203 Ukrainians indicate that 74% had not received the mental health care they required for reasons including limited awareness of where to access care, stigma or feeling embarrassed, as well as fear of not being able to afford care. Much of this hesitation is a result of distrust of psychiatrists and mental health professionals which can be traced back to the Soviet era. This provides a greater imperative for European governments, with support from U.S.-funded organizations, to enhance the capacity of their health systems, as well as local health staff, to accommodate these growing needs.

Unprepared Health Systems

Health systems across the EU are currently unprepared to meet the increasing mental health needs of recent Ukrainian arrivals in addition to ongoing needs of pre-existing refugee populations. Calls for policy reforms to enhance the quantity and quality of mental health care within national health systems already exist, but debates about the types of health provisions that should be provided to refugee and migrant populations, and at what stage of the migration process, has led to fragmented policies for refugees.

To mitigate such knowledge gaps, previous displacement situations, such as the increased migratory pressure to Europe in 2015, have demonstrated the importance of collecting routine, standardized data regarding the health status of refugees across Europe. So far, however, there has been a lack of data on the health status of Ukrainian arrivals in the EU. Resolving critical data gaps potentially includes breaching limitations posed by anti-discrimination laws in several EU countries that prevent the collection of information by ethnicity – information that is key to understanding health access inequities. It also requires increased funding to be allocated to advancing research to regularly monitor refugee health needs.

Another major concern is the lack of psychologists, psychiatrists, and other mental health professionals in European host countries to accommodate the growing need for the provision of MHPSS services for recent Ukrainian arrivals, as well as pre-existing needs among other refugee groups. More recently, the World Health Organization has established EU-wide Mental Health Working Groups that can bring together various stakeholders to coordinate the MHPSS response. This includes experts from across the EU who have experience working with other displaced populations.

“There is a need to really ensure that there are effective MHPSS coordination mechanisms at the national level, and ensure they are well connected to the MHPSS coordination mechanism at the global level,” Whitney suggested. “This then helps everyone have a sense of who the various MHPSS actors are, what their current activities are, allows for opportunities for different collaborators to work together and to prevent duplication of efforts.” USAID and the Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance can facilitate global coordination efforts such as these to scale up humanitarian coordination initiatives and information management.

Other recommendations include the implementation of a comprehensive public mental health strategy, including outreach services led by the host community, and collaborations across health care and social service sectors. These strategies should include comprehensive communication plans to give displaced individuals access to more information about what care they can find and where they can find it. For example, the Ministry of Health in Poland issued an announcement to individuals who were previously receiving psychiatric care in Ukraine, ensuring access and providing resources for ongoing care in Poland.

EU mental health systems should not only provide universally accessible mental health services but also be prepared to train health professionals to understand and treat the specific needs of Ukrainians and other diverse refugee and migrant populations. “It’s crucial to identify local partners and local expertise and to cultivate those partnerships and collaboration so that we can build on existing local knowledge and capacities,” Whitney said. In addition to international organizations funded by the U.S., such as UNHCR and IOM, EU systems also should support community-based organizations that can implement more localized MHPSS initiatives.

Academics and mental health experts have been key to creating, implementing, and evaluating MHPSS interventions outside of the traditional health system. For example, the STRENGTHS program in the Netherlands delivered training to Syrian refugees in Problem Management Plus, a low-intensity psychosocial intervention that can be delivered to fellow refugees in need. Self-guided MHPSS interventions, such as online- or app-based programs, were found to be widely accepted by refugee populations by reducing potential barriers to accessing traditional mental health services, such as stigma. Along the same lines, digital mental health interventions, including telemedicine, should be explored to scale up the provision of services and supplement gaps in the existing health systems, such as by recruiting Ukrainian- and Russian-speaking mental health professionals to deliver care virtually.

Social Integration

Refugees have fled their countries of origin to seek a better life and have a right to health and well-being, which is often compromised by systemic challenges. This places a disproportionate level of power at the hands of stakeholders across the EU, including policymakers, politicians, and program staff with stakes in deciding the future of refugees and asylum-seekers in each country. It also leads to the fear reportedly felt by refugees and asylum-seekers who choose not to disclose their experiences of mental health problems to mental health professionals or other individuals who could offer support – leading to a significant underestimation of the impacts of chronic uncertainty on the well-being of these populations. As such, questions of positionality and power are critical in the consideration of future interventions to support refugees and asylum-seekers across their migration journey, particularly when integrating into a host country.

A key example is the contrast in the largely empathetic international response to Ukrainian arrivals to Europe and the discriminatory rhetoric and anti-immigrant sentiment propagated by European politicians and host communities toward previous arrivals, the majority of whom were from the Middle East and parts of Africa. This has led to calls of blatant hypocrisy and racism in policies that accommodate recent Ukrainian arrivals in comparison to their Black and Brown counterparts. While this reveals the unfortunate and politicized nature of refugee protection provisions globally, it also provides an opportunity to take action and mitigate the devastating impacts of displacement for recent Ukrainian arrivals, as well as the millions of individuals with temporary protection status already in Europe.

With a unanimous activation of temporary protection granted to all Ukrainians arriving in Europe, recent arrivals have access to up to three years of rights that facilitate their integration. This includes access to housing, health care, employment, and education. Family reunification should also be a key part of this response. This stands in contrast to the experience of non-Ukrainian refugees in Europe, who have recounted the impacts of integration challenges on their mental health, and vice versa. This led to chronic uncertainty, which can have negative effects on mental health and motivation to pursue integration activities, including learning a language, pursuing additional schooling or training, or finding employment.

In what has been called a “reckoning” for Europe, the united response toward the Ukrainian situation should increase responsibility sharing among European countries. Inclusive policies that allow Ukrainians access to the labor market, the health system, and to legal residency should be expanded to the millions of other forcibly displaced communities in the EU. Conversely, resources that have been diverted toward the Ukrainian response effort cannot be used as an excuse by host country governments to avoid continuing to expand health systems to accommodate refugees and asylum-seekers from other countries. Lessons learned from millions of previous refugee arrivals should not be ignored; a mental health crisis is at stake.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of the New Lines Institute.