A New U.S. Approach to the Pacific Island Countries

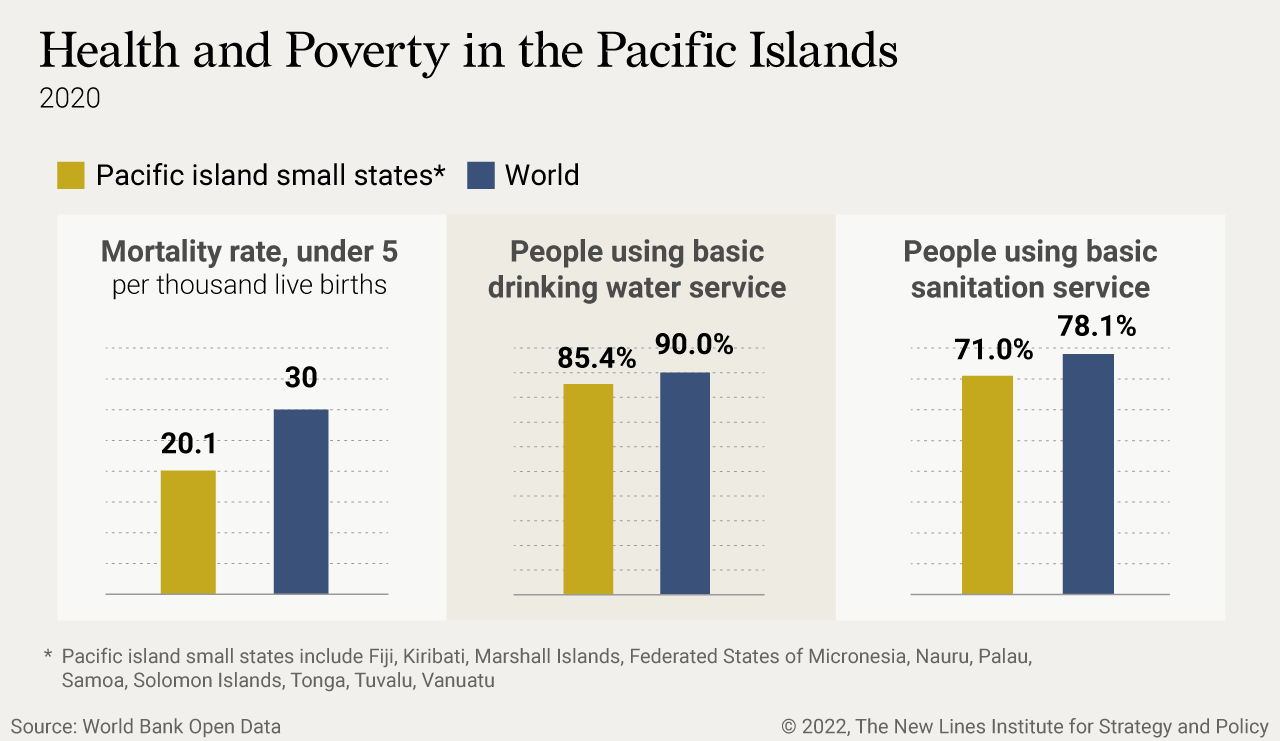

As the U.S. revitalizes its engagement with the Pacific Island countries, it should reconsider its historical approach to the region. These 12 island countries, each with their own culture and politics, command critical influence over global trade, international security, and key ecologies. U.S. security policy and nuclear testing has contributed to economic and environmental vulnerability in the region that has left the door open for influence from China.

Given the ongoing Compact of Free Association (COFA) renegotiation between the U.S. and several Pacific Island countries, now is the time for Washington to reconsider its approach to the region. A model that centers human security and elevates regional climate and economic concerns will win the Pacific Island countries’ long-term trust, support U.S. strategic goals, and improve health outcomes across the region.

U.S. Policy Relevance

The Pacific Islands are critical to Indo-Pacific trade and to the international rules-based order that the U.S. claims to protect. The COFAs – bilateral agreements between the U.S. and the Marshall Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, and Palau – trade aid for military access and create a sort of “power-projection superhighway” for the U.S. in the Pacific. The U.S. is particularly interested in the Micronesian region, as it relies on these islands for its force projection into East Asia. Meanwhile, key U.S. allies Australia and New Zealand have historically focused their efforts on Melanesia and Polynesia, respectively.

While the Pacific Island countries lack the raw density of trade routes found in the South China Sea, they populate critical routes for Australia, New Zealand, Japan, South Korea, and a host of other U.S. partners in South America and East Asia. Natural resource extraction from these countries is a nearly $12 billion market, and almost half of those resources return to China in an extractive dynamic that leaves minimal proceeds for the hosts.

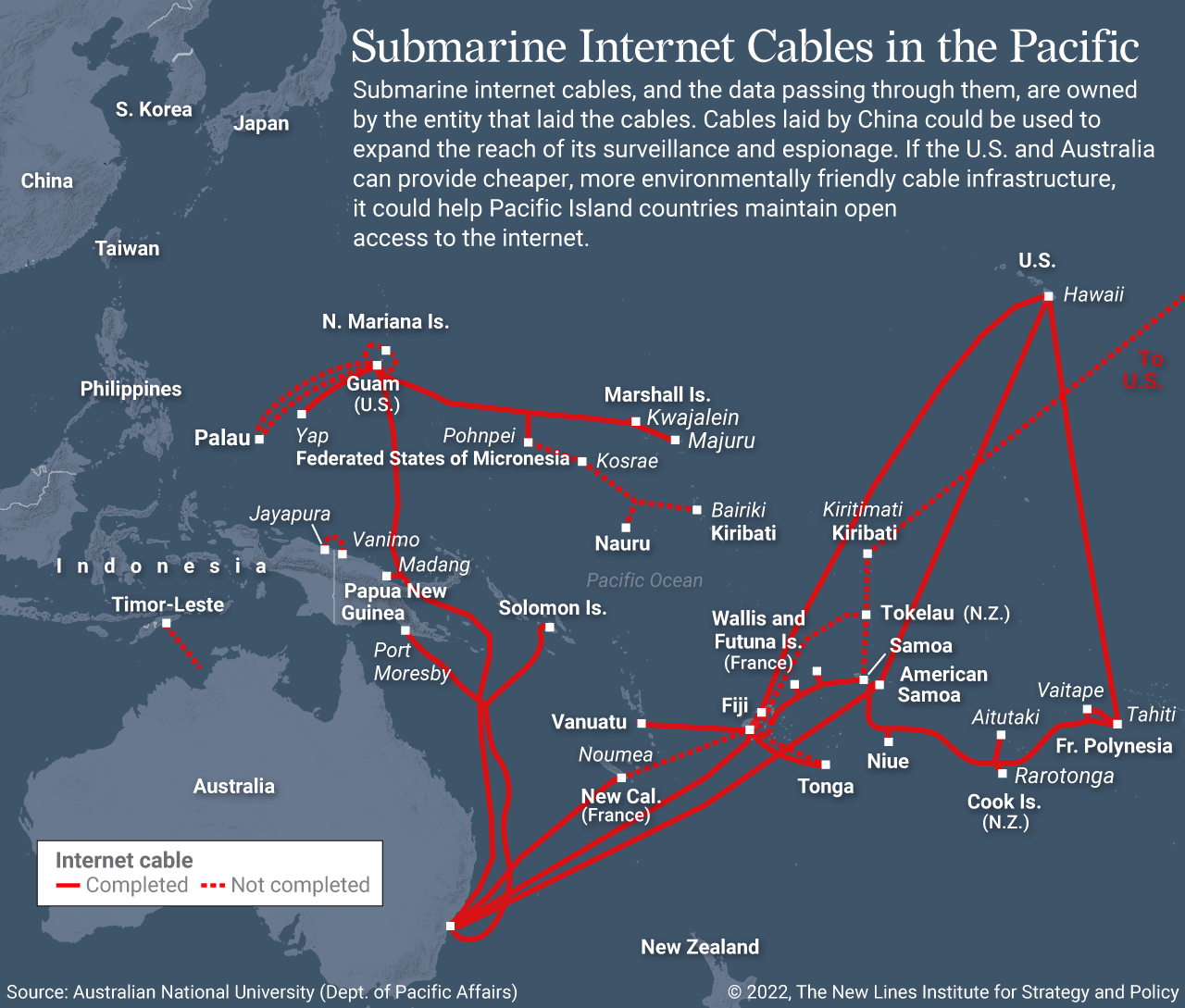

Pacific Island countries are also located alongside critical undersea internet cables, many of which connect U.S. military bases, Hawaii, and Australia to the broader region. For years, the U.S. could depend on Australian or American companies to lay these cables and build other telecommunications networks, which would ensure a high level of security for U.S. communications across the region. More recently, however, Chinese companies have been expanding their foothold in the region’s information and communications technology (ICT) infrastructure. This can create a number of challenges for U.S. and allied security interests, including issues with surveillance, sabotage, and data exfiltration.

Existing efforts to constrain the expansion of Chinese ICT infrastructure in the South Pacific have been largely uncoordinated and haphazard. Washington and Canberra have mainly resorted to emergency funding of critical undersea cables to block companies like Huawei from gaining a foothold or frantic national security warnings. These methods may have been successful in the past, but the growing market power of Chinese telecommunications companies offers little reassurance for future outcomes. Furthermore, as Pacific Island countries continue to rapidly digitize, the adverse effects of Chinese ICT infrastructure will only expand across the region. Washington and Canberra therefore need a more coordinated policy to counter Chinese ICT influence in the region and ensure that democratic norms and values surround the deployment of Pacific ICT infrastructure.

U.S. Regional Legacy

The Pacific Islands are best known to most Americans for their role in World War II, when they served as critical refueling and basing sites for a planned U.S. attack on the Japanese mainland. At the onset of the Cold War, U.S. engagement with the region fell into two broad categories. The first was nuclear testing; from the late 1940s until 1958, the U.S. conducted extensive nuclear tests in the Marshall Islands, releasing massive amounts of radiation, causing irreparable environmental damage, and destroying at least four islands. The Marshall Islands can no longer grow its own food, and the population relies on imports of heavily processed foods, generating the world’s highest obesity rates and commensurate rates of diabetes.

Second was involvement in the administration and defense of the region. In 1947, a U.N. mandate placed the islands of Micronesia under the administration of the U.S. in what became known as the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands. In practice, this meant the U.S. Navy defended the islands and the U.S. Department of the Interior managed administrative affairs. Motivated by the decolonization movement, these areas were given a choice: become U.S. territories or become sovereign states with the option to sign a COFA with the U.S. The Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands opted for commonwealth status in the late 1970s, but Palau, the Federated States of Micronesia, and the Republic of the Marshall Islands chose to become freely associated states. Palau’s COFA came into force in 1994, and Micronesia and the Marshall Islands’ COFA came into force in 1986.

With the signing of these COFAs, the Marshall Islands, Micronesia, and Palau became known as the Freely Associated States (FAS). These agreements have become foundational elements of the United States’ Pacific strategy, and the FAS have been some of the United States’ closest partners. In the years since the COFA agreements came into force, however, U.S. policy has taken the region’s political support and security cooperation for granted, testing the limits of the relationship. As a result, U.S. officials have found the tipping point where these countries’ support for the U.S. is no longer assured.

This legacy has played a role in shaping the region’s high level of economic vulnerability and how China and U.S. engage with Micronesia today, with China seeing an opportunity for a foothold and the U.S. seeing an urgent need to counter Beijing’s influence.

China’s Approach

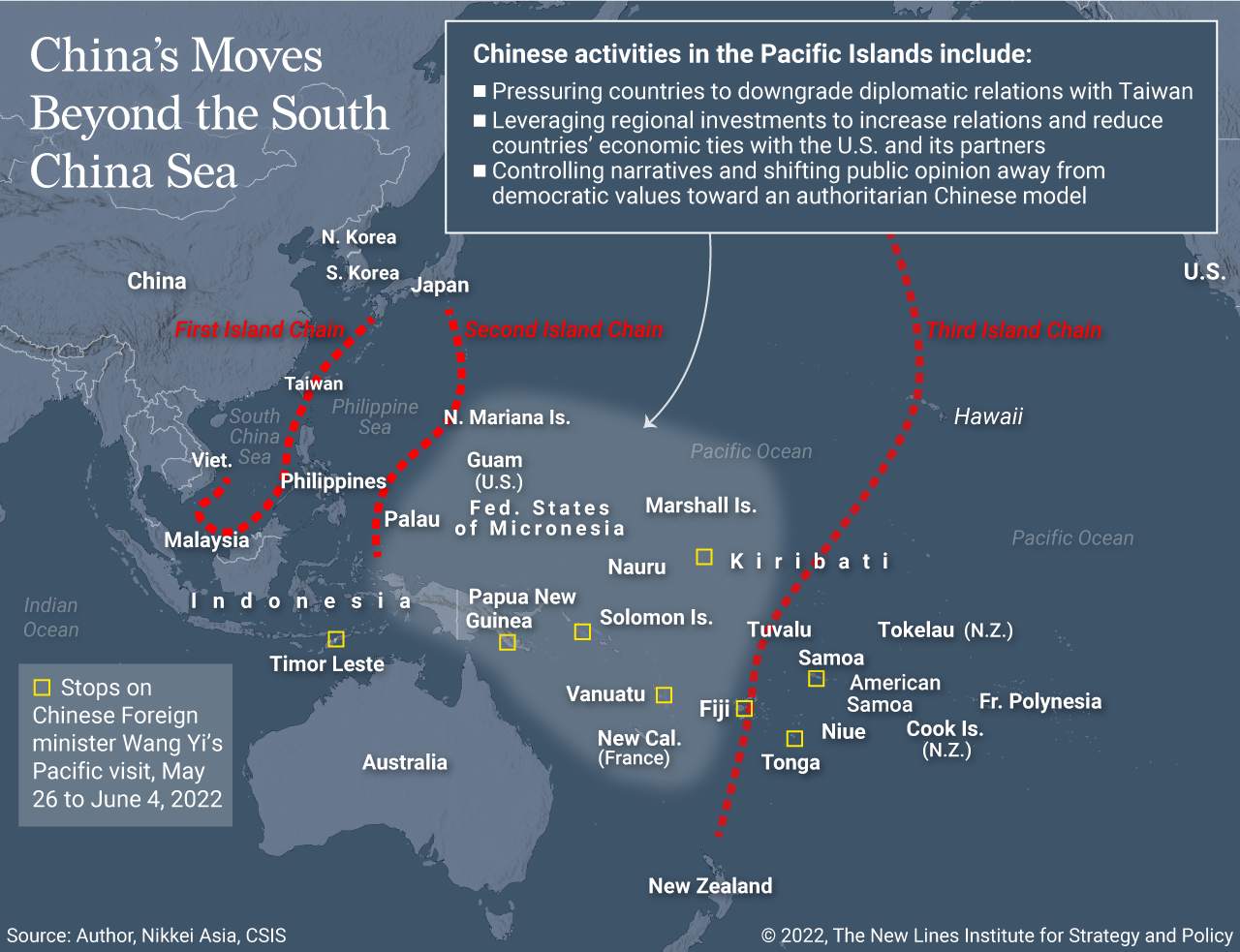

China is advancing its control over the South Pacific to push U.S. influence back off the second island chain—China’s second line of defense arcing from Japan to Papua New Guinea, which it sees as necessary to maintain homeland security and limit Western encroachment. Fighting elite and popular skepticism of its motives, China has manipulated economics and information to achieve these ends.

China uses a number of diplomatic tactics to advance its interests, but its most visible efforts surround its campaign to deprive Taiwan of a diplomatic base in the Pacific Islands. In 2019, Chinese officials’ successfully pressured the Solomon Islands and Kiribati to switch diplomatic recognition from Taipei to Beijing. Reports indicated that promises millions of dollars in aid – in what has been termed “checkbook diplomacy” – sweetened the deal. Beijing similarly tried to pressure the Marshall Islands into switching recognition by offering extensive Belt and Road financial assistance and allegedly bribing local Marshallese politicians. Fiji and Papua New Guinea also closed or downgraded their relationships with Taipei in recent years after pressure campaigns from Beijing.

Beijing has been patiently expanding its influence in the Pacific media environment since the early 2000s, with its involvement in recent years taking on an increasingly aggressive tone. Australian journalist Sue Ahearn writes that “most Pacific media organizations are struggling financially; many journalists have lost their jobs and China is offering a way for them to survive – at the cost of media freedom.” Beijing has swooped in to “court the media with money, junkets and propaganda.” It offers journalists “exchange programs, opportunities to study in China, tours and financial aid for their media outlets” and has even provided news outlets with equipment and covered maintenance costs.

China has successfully chilled criticism from Pacific Island media. The former media director at Vanuatu Daily Post, for example, faced extensive pressure and was ultimately barred from returning to Vanuatu after running a story on the Vanuatuan government’s willingness to enforce Chinese law on its soil. An Australian producer faced direct pushback, threats from Chinese embassy officials, and censorship attempts over the production of a “60 Minutes” report on China’s debt-trap diplomacy in the Pacific. Similarly, a Papua New Guinean journalist was suspended from his position due to his work exposing a scandal involving Chinese officials. During senior Chinese diplomat Wang Yi’s May tour of the region, Wang and other Chinese officials squelched media coverage, refusing and removing journalists who asked non-approved questions. Each of these activities is damaging in and of itself, but when merged together they paint a frightening picture for the future of press freedom, government accountability, and democratic stability in the region.

China also has invested heavily in Pacific civilian infrastructure, and many Pacific Island countries are part of the Belt and Road Initiative. While reports indicate that China has not yet engaged in debt-trap diplomacy in the region, many observers are concerned that this investment could bring Pacific politicians closer to Beijing’s interests.

China’s investments include projects near U.S. basing. One of the most consequential incidents occurred in the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, a U.S. territory. After the commonwealth legalized gambling in 2014, a number of Chinese investment firms announced plans to invest in casino resorts adjacent to Department of Defense-leased land. The subsequent rise in PRC investment and tourism coincided with increased tensions surrounding the department’s plans to use the land. Local business interests began to prefer the economic benefits of the Chinese casinos, arguing that the U.S. training area limited the area’s economic potential.

China also has engaged in exploitative resource extraction – notably illegal, unregulated, and unreported fishing, which is detrimental to Pacific economies, the livelihoods of fishers, and the sustainability of Pacific fisheries. Left unchecked, it poses a direct threat to global maritime governance and the stability of Pacific communities.

Furthermore, Beijing has weaponized tourism, a critical part of many Pacific economies. From 2011 to 2015, Chinese tourists to Palau made up more than 50 percent of annual visitor arrivals, but at the end of 2017, this came abruptly to an end as Beijing banned state-run package tours and cut the number of flights to Palau. Observers widely interpreted this as an effort to pressure Palau to switch its diplomatic recognition from Taipei to Beijing and remind its leaders how dependent their economies are on China.

Policy Recommendations

While the Biden administration has recognized the importance of amping up the U.S. presence in the Pacific Islands, it continues to rely on the traditional, thinly veiled military and geostrategic playbook. It has focused on bolstering the diplomatic presence, high-level diplomatic summits, sharp increases in financial assistance for pre-existing programs, and re-establishing development programs that had been terminated when the Pacific Islands failed to claim the highest geostrategic priority. These efforts are needed and laudable but are not enough to build enduring partnerships.

The U.S. needs a new approach to the region. First, Washington should approach Pacific Island leaders as equal partners in a joint venture when negotiating these policies. Second, to build long-term partnerships, the U.S. may have to pay short-term costs and pursue programs that do not explicitly benefit the U.S. but are of high priority to these countries. Third, the U.S. must downplay geostrategic competition with China during negotiations, as the countries have explicitly expressed their desire to stay out of U.S.-China competition. Fourth, the new approach should elevate and center the real human security needs of Pacific Islanders.

The U.S. should increase funding for and cooperation within USAID’s Pacific Island climate initiatives. This effort should be couched in larger diplomacy as no set of local climate policy programs will be successful, or credible, unless underpinned by high-level action in accordance with the Paris Climate Agreement. Climate change is the top security challenge for these countries, and U.S. action on this issue is critical to building long-term trust. The Biden admin has proposed $810 million of new spending, much of which focuses on climate-related initiatives, including efforts focused on biodiversity maintenance and the development of infrastructure to endure changing seas and extreme weather events.

The U.S. should increase funding to these programs to change two elements of its current approach. First, it should ensure that Pacific Islanders take part in these projects as key stakeholders and participants. Second, the U.S. should adopt a concerted public diplomacy campaign to highlight its efforts and counter Chinese disinformation as a means of building popular trust.

Another way to reinvigorate U.S.-Pacific Island relations is to reestablish social safety net support on ethical and national security grounds. The original COFAs stipulated that the U.S. would provide assistance for health care and made FAS citizens eligible for Medicare and other federal assistance programs when they resided in the U.S.; this served partially as a form of reparations for Cold War nuclear testing. Congress, however, terminated the program with the 1996 welfare reform law and left FAS citizens with only access to emergency medical care and disaster relief services.

The termination has had far-reaching adverse effects. From a humanitarian and ethical standpoint, the U.S. withdrew necessary medical assistance that emerged from a problem it created. From a national security perspective, it has created economic vulnerability in the FAS and U.S. territories that has provided an opportunity for China to gain a foothold. If the U.S. continually fails to support Pacific Islanders’ needs, they may turn to China out of financial necessity, despite a preference for the U.S.

Extending existing federal public assistance programs to the U.S. territories and the FAS would meet this need. Ideally, this would involve extending all four means-tested programs – Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, Supplemental Security Income, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, and Medicaid – to the U.S. territories and FAS citizens residing in the U.S. as well as extending Medicaid benefits to FAS citizens residing in their respective Pacific countries. The infrastructure for these programs is already in place, which reduces the costs of re-implementation.

The U.S. also should work with its regional allies to develop a coordinated approach to protect undersea internet cables. Efforts to reduce the vulnerabilities of a single connection point, coupled with the region’s rapid digitization rates, mean regional ICT companies can expect many submarine cable projects to emerge in the coming years. The U.S. and its partners must dominate this construction to ensure security and that democratic values surround system deployment.

There are two facets the U.S. should focus on. One angle addresses new cable development. The U.S. should lead an effort to finance cable construction at either a cheaper rate or in a more environmentally friendly fashion compared to Chinese companies. The other angle addresses existing cable protection. While it is unfeasible to constantly monitor the region’s entire network of cables, policymakers have several alternatives that can increase cable security. For example, the U.S. can work with Pacific allies to install sensors and sonar technology to immediately detect tampering before laying down new cables. It could also work with regional allies to conduct dynamic patrols of vulnerable areas and provide training to Pacific security forces. China does not have a vested interest in securing these cables, which creates a unique opportunity for constructive U.S. engagement with the region.

U.S. should establish a preferential market access program in the Pacific Island countries. The Biden administration has tried to address its Pacific economic engagement with the recently announced Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity, but this framework fails to meet the Pacific Island countries’ needs. Critics point out that it excludes the countries – Fiji is the only one party to the framework – and fails to include the market access stipulations low-income economies typically desire.

Establishing a preferential market access program akin to what the U.S. has pursued in Africa with the African Growth and Opportunity Act and in the Caribbean with the Caribbean Basin Initiative is necessary to provide visible economic support to Pacific Island economies. These programs are designed to help develop and diversify low-income economies. They also strengthen economic ties, can be used as a tool to edge out Chinese economic activity, and serve as a form of foreign aid without drawing dollars away from the U.S. foreign aid budget. To complement the trade program, U.S. policymakers should also streamline customs processes and address logistical trade barriers as easy improvements to trade relations without having to change U.S. law.

This research was originally sponsored by the National Security Innovation Network X-Force Fellowship program and led by Dr. Corey Bergsrud at Naval Surface Warfare Center – Crane Division in Crane, Indiana. Through the program, Bergsrud gave fellows the problem statement, “Designing Narratives Across the Diplomatic Information Military and Economic for Maritime Gray-Zone Operations.” Bergsrud further focused the framework on the Pacific Island countries.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of the New Lines Institute.