The Turkish government wants to shut down the Democratic Peoples’ Party in Ankara’s latest attempt to ban a popular pro-Kurdish party. This second installment of a three-part analysis looks at the HDP’s options and the historic strategies pro-Kurdish parties have used to gain a presence in the Turkish Parliament. Read the first part here.

Editor’s Note: For the purposes of this analysis, the author uses “pro-Kurdish” to describe a particular facet of Kurdish representation and activism: the promotion of Kurdish culture, political involvement, and Kurdish identity. There have always been Kurds active in Turkish politics working outside of this pro-Kurdish definition. This analysis centers on the work of pro-Kurdish political parties and is not meant to be an all-encompassing account of Kurdish involvement in Turkish politics.

A newly accepted indictment aims to ban more than 600 politicians and members of Turkey’s pro-Kurdish Democratic Peoples’ Party (HDP). The survival of the HDP and its sister party, the Democratic Regions Party (DBP), is an unknown element in the 2023 elections, even as the party seems to be on board to stand behind a single opposition presidential candidate.

The party will likely be the key to the opposition’s attempt at an electoral breakthrough in 2023. If the HDP can maintain the strategies and success of its past in attracting both Kurdish and leftist voters and survive until the next election, it could wield its power as the third-largest party to enact the opposition’s shared goal of re-empowering parliament. The evolution of the pro-Kurdish parliamentary project through the use of independent candidates, frequent party name changes, immunity and revocation, and finally with a leading party of its own offers insight into the many remaining options still available to the HDP.

The Many ‘We’s’ in Parliament

In 1991, Leyla Zana, the wife and cousin of the famous Diyarbakir mayor Mehdi Zana, arrived at her parliamentary inauguration donning the Kurdish red, yellow, and green. Her outfit alone caused outrage. Zana was the first Kurdish woman to enter Turkish parliament. She concluded her inaugural oath with a statement in Kurdish: “I shall struggle so that the Kurdish and Turkish peoples may live together in a democratic framework.” At the time, Kurdish language was still banned from use in public. Zana’s parliamentary immunity prevented her arrest until the party she belonged to was banned in 1993. Zana was then sentenced to a 15-year term – the first of multiple prison sentences she would serve during her career.

The rest of Zana’s 1991 cohort faced severe threats both to their posts and personal security. Among other assassinations, Robert W. Olson wrote in his 1996 book “The Kurdish Nationalist Movement in the 1990s: Its Impact on Turkey and the Middle East,” a Democracy Party MP was shot and killed in Batman. After fierce debate within the party and several bombings of party buildings, Olson wrote, the Democracy Party withdrew from the 1994 election. As a result, Zana was one of the last politicians to represent the pro-Kurdish cause in parliament until 2007. The next wave of pro-Kurdish parties would eventually evolve into the HDP.

Party Closure

Just as Zana’s parliamentary immunity protected her in 1991, other pro-Kurdish members of parliament have relied on their immunity and therefore their status as MPs to avoid arrest. This reliance on parliamentary immunity and frequent party closure created a tradition of a revolving door of Kurdish politicians that enter as members of one pro-Kurdish party and then move to a newly formed one after theirs is banned. The legacy of this well-established process can be traced back to the first pro-Kurdish focused national party, the People’s Labor Party, which survived only three years before being banned in 1993. Despite their growing popularity at the local level, these parties were unable to exceed the 10% parliamentary threshold, yet their very existence represented a threat to nationalist norms. This process has been so consistent that in Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) leader Devlet Bahçeli’s call to close the HDP, he also referenced the need to make sure “the party does not reform under a new name.”

Nevertheless, switching parties is not foolproof. In March 1994, parliament voted to remove the immunity of seven pro-Kurdish MPs and one MP from the Welfare Party. This was the first time a member of parliament had been stripped of their immunity since 1968. This revocation of immunity signaled the end of the pro-Kurdish party’s representation in parliament until 2007. The 2016 revocation of immunity through a new constitutional amendment initiated a mass purge, Kurdish affairs expert and political science professor Dr. Nicole Watts wrote in her 2011 book, “Activists in Office: Kurdish Politics and Protest in Turkey.”

Leftist Coalitions

Prior to the formation of the HDP, pro-Kurdish parliamentarians like Zana ran as members of coalitions of smaller parties to break the 10% parliamentary threshold. Pro-Kurdish parties often worked in tandem with their socialist and communist peers, despite divisions over an emphasis on pro-Kurdish issues and attacks on leftist parties themselves, Watts wrote. In the late 1980s the Social Democratic Populist Party (SHP) – a breakaway party from the center-left opposition Republican People’s Party – initiated a new alliance between pro-Kurdish parties and the leftist mainstream, Watts wrote. This alliance continued in 1991, when the parties ran on a joint ticket and the pro-Kurdish People’s Labor Party received 22 deputies. The SHP proved a powerful ally in legitimizing discussion around Kurdish rights, but internal tensions ultimately tore the party in two.

As members of a coalition, Zana and others used their positions for largely symbolic purposes at first. Their ability to affect policy was limited by the boundaries enforced by their strategic allies, regional emphasis, radical activism, competition for the Kurdish vote from conservative parties, the parties’ implied links to the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), and of course the constant closure of the parties themselves.

Shifting to Independent Candidates

After the breakdown of their alliance with the SHP after the 1991 election, pro-Kurdish parties continued to run in general elections, but their campaigns never amounted to actual parliamentary representation. In the 1999 and 2002 general elections, pro-Kurdish parties ran as independents and received no seats. In the 2000s this inability to puncture the uniquely high parliamentary threshold was part of a broader issue for parties outside of the dominant Republican People’s Party and Justice and Development Party (AKP). In fact, in 2002 only two of 18 parties, representing just 55% of the vote, were able to enter parliament.

After 13 years of failing to achieve parliamentary representation as independent parties, pro-Kurdish parties adopted a new strategy. In 2007, members of these parties ran as independent candidates with other leftist parties and formed a bloc once elected in parliament, Watts wrote in “Activists in Office.”1 In 2011, this tactic to circumvent the threshold law proved particularly successful. The Peace and Democracy Party’s (BDP’s) Labor, Democracy and Freedom Bloc gained 36 of the 550 seats in parliament. One of these MPs, then representing Hakkari, would inspire a new kind of pro-Kurdish movement.

HDP’s Dual Approach

Compelled at least in part by the ideals of the 2013 Gezi Park protests, the HDP formulated a revolutionary vision for pro-Kurdish parties: “Biz’ler,” or “the many we.” The newly founded party ran on a platform of plurality and democracy that transcended ethnic and regional divisions. The HDP had a dual approach: pursuing regional goals at the local level through its sister party the BDP (now the DBP) in predominantly Kurdish areas while the HDP expanded beyond its base in southeastern Turkey, adopting a more universal ideology and advocating for democratic values at the national level. In order to create a broader solidarity network, the party opened dialogue with other marginalized groups. HDP representatives dined with Alevi notables, advocated for gay rights, recognized the Circassian and Armenian genocides, adopted feminist and socialist commitments, and rallied behind environmental causes.

The party’s charismatic co-president, Selahattin Demirtaş, formerly BDP’s member of parliament for Hakkari, became the face of the movement. His backstory and peace-oriented speeches enticed leftists across the political spectrum. Demirtaş talked openly about his brief attempt to join the PKK as a teenager. He recalled his early realization that a political movement would be far more effective than an armed struggle and advocated for an end to the violence. Demirtaş went on to gain national clout through his presidential campaigns in 2014 and 2018. Nicknamed the “Kurdish Obama,” he focused on political solutions to the so-called “Kurdish Question.” Although the HDP complained that President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan received disproportionate media coverage compared to his competitors, Demirtaş delivered memorable speeches that aired on national television and reached a more diverse audience. Demirtaş came in third in both the 2014 presidential election and the 2018 election, when he ran for office from prison. These campaigns remade him as a national, rather than a regional, figure.

Breaking the Threshold

In June 2015, the HDP became the first pro-Kurdish party to exceed the 10% required for party parliamentary representation. In fact, the party won 13% of the vote. Eighty pro-Kurdish MPs entered parliament, much to the chagrin of the AKP. This victory moved the HDP beyond the status of cursory Kurdish movement to national opposition party. HDP activists were legitimized and now on the stage of national politics like never before, but the victory was short-lived.

One month later, the HDP’s fragile entrance into national politics was shattered by the deadly Suruc bombing, which took the lives of 34 leftist protesters and injured over 100 others. The HDP and others claimed that the Turkish government was complicit for its alleged negligence toward the Islamic State. The next day, PKK insurgents carried out an attack against Turkish soldiers in retaliation for the bombing, ending the two-year peace process. Allegations against the HDP, anti-Kurdish fervor, and PKK violence soared to new heights over the next two years, crippling the hope of a peaceful political process. The HDP’s launch into national politics in the midst of the PKK’s battle for urban centers across the southeast made for a tumultuous entrance at best. One HDP report cites a slew of violent attacks on their offices across the country over the course of just 6 days in September 2015. HDP representatives attempted, and failed, to negotiate an end to the violence.

Four months after the Suruc bombing, Erdoğan called for a snap election to break the hung parliament. The HDP lost 21 seats. Despite this setback, HDP representatives used their positions to call attention to issues plaguing their constituents across the southeast in the midst of increasing violence. As the security situation worsened and the Turkish government reinstated curfews and a kind of martial law called OHAL (State of Emergency Rule) across the southeast, the HDP organized peaceful protests to demand an end to curfews and to promote peace talks. Demirtaş himself visited the family of one of the Turkish soldiers killed in the Hendek Wars, emphasizing that the violence was causing tragedy on both sides of the conflict.

Since then, 3,695 of the HDP’s co-chairs, deputies, provincial-district co-chairs, directors and party members have been arrested, and more than 5,311 people have died as a result of the PKK conflict.

The Government’s Tactics Against Pro-Kurdish Parties

The PKK Narrative

The vast majority of investigations and legal prosecutions against pro-Kurdish politicians are conducted under the pretense that their party supports the U.S.-listed terrorist organization, the PKK. In the past, opponents of pro-Kurdish parties could easily trap politicians in their understated support for the PKK, praise of the imprisoned and now largely symbolic PKK leader Abdullah Öcalan, or simply their refusal to condemn the organization outright. Even pro-Kurdish politicians less than supportive of the PKK were beholden to their often pro-PKK base. Historically, this resulted in a practice of subtle references to the group in combination with several others conducting brazen acts of support.

In contrast, HDP leaders have generally refrained from direct references to the PKK, instead emphasizing political participation. While many members still openly praise Öcalan and call for his release, for Demirtaş, Öcalan’s role is clear. Demirtaş had been negotiating with Öcalan for a cease-fire since 2013. In a 2018 op-ed, Demirtaş bluntly said Öcalan “has considerable influence among the Kurds in Turkey and Syria … in any potential peace process, the PKK will listen to no one but Öcalan himself.” However, in a recent statement from prison, Demirtaş seems to have changed his stance. Perhaps in recognition of Öcalan’s diminishing relevance, he stated that “parliament is where the Kurdish question is to be resolved,” not, as his HDP peer suggested, in the prison where Öcalan is being held.

In 2015 the breakdown of the cease-fire pushed the HDP’s position as an interlocutor to the brink of collapse. The HDP again served as an intermediary between Öcalan’s followers in Qandil and the Turkish government. This process only served to strengthen the views of some that the HDP and the PKK were but two parts of the same organization. The HDP could hardly afford to abstain from these talks, and yet their inclusion seemed to align them with the same violent actors the party swore to replace.

Beyond initiating investigations against party members, opponents of pro-Kurdish parties also worked to mold the national discourse. The Turkish government uses the term “separatist terrorists” to describe the PKK in order to avoid recognition of their “Kurdish” identity. This framing divorces them of their political environment and the Kurdish struggle entirely. Pro-Kurdish parties view violent insurgency as a symptom of Kurdish inequality. Attempts by Kurdish politicians to contextualize and reinstate “Kurdishness” into the equation are generally taboo, as such moves would re-introduce ethnicity into the monoethnic identity of the Turkish Republic. These divergent narratives also alienated pro-Kurdish parties from their allies. Most prominent Turkish political parties rely on nationalist approaches to Turkish identity (although in a variety of flavors and degrees). Thus any linkage with the violent attacks of the PKK pushes lawmakers into national unity against perceived security threats.

The creation of a “Kurdish” enclave in northeast Syria in 2013 further inflamed tensions over the PKK. A great number of HDP representatives were arrested for, and continue to be investigated over, their speeches condemning Turkish inaction during the siege of Kobane. The launch of Turkish operations in northeastern Syria against the YPG, and the Syrian Democratic Forces more broadly, intensified nationalist rhetoric about the PKK and motivated AKP officials to curb protests that referred to the YPG as anything but terrorists. The “HDP equals PKK, equals YPG, equals PYD,” Erdoğan declared in 2019. Therefore, the historic ties between Syrian Kurds and Turkish Kurds, particularly those involving the movement of militants across the border, transformed international conflicts into domestic divisions. The PKK and its affiliates and allies moved in Syria and Iraq, while the HDP labored in Turkey.

The End of Parliamentary Immunity

In May 2016, a constitutional amendment put an end to the long-held practice of parliamentary immunity. Six months later, party leader Demirtaş and co-leader Figen Yüksekdağ, alongside 10 other HDP members of parliament, were arrested.

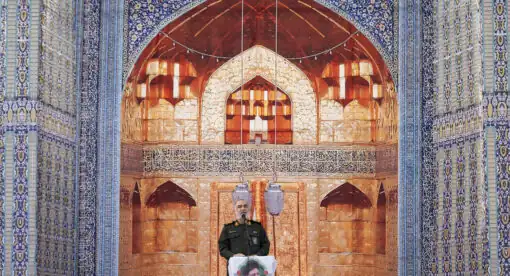

In the years that followed, opponents have slowly whittled away at the HDP’s parliamentary members. New investigations piled on, and arrests followed in small batches. One of the latest arrests drew international attention. Former MP Ömer Faruk Gergerlioğlu was arrested mid-prayer earlier this year and taken into custody with only one shoe on. Notably, this is not the first time Gergerlioğlu had been threatened with arrest. He was previously fired from his civil job by the Turkish government for sharing a post on social media, and in 2016 he was investigated for a separate social media post and sentenced to two and a half years in prison. Gergerlioğlu gained parliamentary immunity in 2018, effectively evading this sentence. Pictures of Gergerlioğlu’s prison grab bag outside the mosque circulated on Twitter, evidencing the precarious position pro-Kurdish representatives put themselves in when elected to office. Prison sentences are more often than not the norm for the candidates. In a break from tradition, however, the Turkish Constitutional Court recently ruled that his imprisonment and ban from politics was unconstitutional, and he was released July 6.

On Feb. 21, 33 new legal proceedings were launched targeting nine HDP parliament members. The new investigations involved the 2014 Kobane protests. Notably, the investigations were announced shortly after a botched hostage rescue resulted in the execution of 13 Turkish citizens by the PKK as the Turkish military advanced on their cave bunker in Iraq. The MHP leader, Bahçeli, made headlines as he proclaimed that the new legal proceedings offered a “historic opportunity to settle accounts with divisionism and terrorism.” DBP co-chair, Keskin Bayındır, claimed that the move could be viewed as “a gift to the MHP.”

The HDP’s Precarious Position

The future of the HDP’s parliamentary membership will depend largely on the cooperation of the other opposition parties and the rulings of the higher courts. In 2016, these parties voted in favor of revoking parliamentary immunity, resulting in the beginning of the end for the pro-Kurdish movement’s expansion. Yet if the opposition intends to take back parliament from the grip of presidential power, they will have to accept that the HDP may very well be the key to parliamentary majority and success in the presidential election.

Without parliamentary immunity, the HDP faces new existential threats in the two years before the next election cycle. These threats are emerging against the backdrop of increasing ultra-nationalist rhetoric on the part of Erdoğan and his electoral partner, Bahçeli, as the president expands his purge of politicians and dissenters. Part three of this terrain analysis will discuss the role HDP has to play in the opposition coalition and the potential approaches the party could use if it is banned.

Kayla Koontz studies Kurdish insurgent groups and political movements in Turkey, Iraq, and Syria. Koontz holds an MA from UC Berkeley in Global Studies. She has previously written for the Middle East Institute and Bellingcat and studied and worked in Turkey. Follow her on Twitter at @kay_koontz.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of the New Lines Institute.