As it forces countries around the world to rethink their strategies, the COVID-19 pandemic could allow the United States to improve its troubled relationship with Russia.

The global coronavirus crisis is likely to have geopolitical effects for years, if not decades, to come. Indeed, the entire global order could shift as the world’s major powers – from the United States to China to Europe to Russia – all cope with the crisis in different ways. One particular relationship that could see important changes in the post-corona era is the one between the United States and Russia. Washington could have opportunities to decrease tensions with Moscow and improve the U.S. strategic position globally.

U.S.-Russian Relations before Coronavirus

Prior to the pandemic, U.S.-Russian relations were arguably at their lowest since the end of the Cold War. The pro-Western EuroMaidan revolution in Ukraine in February 2014, which overthrew a Russian-backed government in Kiev, catalyzed a prolonged standoff between Washington and Moscow. Russia’s subsequent annexation of Crimea and support for a separatist rebellion in Eastern Ukraine triggered U.S. (as well as EU) sanctions against Moscow and sparked a major military buildup by both NATO and Russian forces throughout the European borderlands.

The Ukraine crisis had several other important, longer-term effects. As the United States has maintained and steadily increased sanctions against Russia over the past six years, Moscow has pursued a structural repositioning of its foreign policy away from the West and toward the East. This included an expansion of already growing economic and security ties with China, as well as a deepening involvement in areas of strategic interest to the United States, particularly in the Middle East.

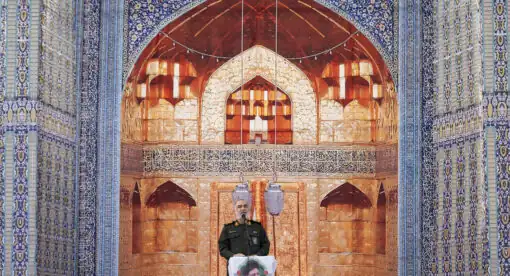

Russia’s military intervention in the Syrian conflict on the side of the Assad regime can be seen as a key component of this shift. The Kremlin had several motives for its involvement in Syria. According to the Kremlin’s official account, Russia was concerned about the proliferation and spillover of Islamist militant groups like ISIS onto its own territory. But more importantly, Moscow wanted to preserve its existing assets in Syria like the Tartus naval base, and to gain leverage against Washington in what was bound to become a prolonged standoff.

Notably, the grounds for Russia’s intervention in Syria resembled that of its actions in Ukraine in important ways. As with the overthrow of the Ukrainian government led by Viktor Yanukovych, a Syrian government led by Bashar al Assad, which Moscow viewed as legitimate, came under attack from Western-backed opposition and Islamists, which Moscow viewed as illegitimate. In this sense, Russia challenged the rationale behind U.S. actions in these theaters based in part on promoting democracy and human rights, and Moscow adapted (or rather refined) a de facto doctrine of direct involvement against U.S.-backed efforts at regime change in foreign countries.

Russia subsequently applied this doctrine in other areas outside of the region, notably in Venezuela. As the United States pressured Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro in recent years through sanctions and support of the country’s political opposition, Russia has increased its economic and security support for the Maduro regime. Moscow had many reasons for this intervention, including gaining leverage over the United States, protecting Russian energy assets in Venezuela, and helping Maduro’s regime fight U.S.-supported opposition forces.

As a result of Russia’s involvement in Syria, Venezuela, and other theaters from Europe to South Asia to Africa, Washington has ratcheted up pressure on Moscow in the form of expanding sanctions and increasing military support to anti-Russian allies. In the context of military build-ups by Russia and China’s growing military sophistication, the United States has also left arms control pacts with Russia like the INF (Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces) treaty. Thus ensued a prolonged standoff that spanned the globe and manifested in arms control, elections meddling, and sanctions – circumstances that have framed U.S.-Russian relations for most of the past decade.

U.S.-Russian Relations During the Pandemic

Now, at the onset of the new decade, the coronavirus pandemic is forcing a re-evaluation of policies across the world, both on the domestic level and in terms of foreign policy.

In Russia’s case, there have already been major political and economic implications. Even prior to the outbreak, Russia had begun a process of internal political consolidation through constitutional amendments which would, among other things, allow Russian President Vladimir Putin to rule for another two terms, or 12 years. These amendments saw swift passage in both houses of Russia’s parliament earlier this year and were set for a public referendum in April before postponement due to the coronavirus outbreak. If and when the referendum is held, the amendments are all but guaranteed to pass, in no small part due to the majority of Russian citizens’ desire for strong leadership and political stability at the top levels of government in times of crisis.

On the economic front, the pandemic is particularly damaging to Russia, given the reliance of its economy on the energy industry and the precipitous fall of global oil prices since the outbreak. Even prior to the coronavirus crisis, Russia’s economy had become stagnant, growing just 1.3 percent in 2019, according to Rosstat. Nevertheless, largely because of the prolonged nature of U.S. sanctions, the Kremlin had been able to weather the sanctions regime by insulating its economy from external shocks. Russia pursued a conservative fiscal policy and built up its foreign currency reserves and national wealth fund to over $400 billion and $150 billion, respectively; increased its domestic agricultural output while banning imports from the United States and Europe; and set its 2020 budget to a low (at the time) oil price of $42 per barrel.

However, the coronavirus has caused a dramatic drop in global oil prices which, combined with Russia’s production cuts dispute with Saudi Arabia, has put tremendous economic strain on Moscow that will test the endurance of its recent strategy. While Russia and Saudi Arabia, along with other OPEC members, finally reached a compromise on April 12 to cut oil production by nearly 10 million barrels per day, the quick fall in oil prices days later exposed Russia’s economic vulnerability. The oil price drop is likely to hurt Russia more than it will more diversified economies like the United States and China.

In this context, there have been two notable developments in U.S.-Russian relations recently. On March 28, Russian oil giant Rosneft announced that it would cease operations in Venezuela and that it would be transferring its entire stock in Venezuela’s PDVSA to Roszarubezhneft, a little-known, state-owned Russian energy firm. This could be seen as a sign of Russia’s growing vulnerability to U.S. sanctions as its energy industry suffers, and of Moscow’s increased willingness to adjust its operations in strategic theaters like Venezuela. Additionally, on April 3 reports emerged that the United States had received a shipment of ventilators from Russia’s KRET tech firm, a subsidiary of Russian conglomerate Rostec, which is currently subject to U.S. sanctions. It remains unclear whether the U.S. Office for Foreign Assets Control issued a sanctions waiver to receive those supplies, but it nevertheless points to Washington’s willingness to be more flexible on its sanctions during a crisis.

A Better Relationship?

Of course, these developments could be relatively minor and circumstantial aberrations that may not portend a major shift in the sanctions policy between Washington and Moscow. There are deeply ingrained drivers in the standoff between the United States and Russia, including overlapping spheres of influence in the European borderlands and the U.S. strategic interest in preventing the rise of a regional hegemon on the Eurasian landmass. Moscow is unlikely to abandon its position in key theaters like Ukraine and Syria, and it should be noted that Russia’s ability to project power – particularly military power – has historically been disproportionate to its economic weakness.

Nevertheless, the current crisis could present the United States with opportunities to improve ties with Russia. Washington’s sanctions, which so far have not been a major deterrent to Russian behavior, could become more potent during a deep, prolonged economic crisis. Depending on the extent of the economic pain Russia experiences – particularly in its energy sector – Moscow could be willing to make further adjustments to its operations in Venezuela and other theaters detrimental to U.S. interests in order to avoid further sanctions.

Washington could also leverage any changes in sanctions on Russia into other areas, particularly China. The origination of the coronavirus in China has sparked a re-evaluation of U.S.-China ties, particularly regarding supply chains. Further severing of trade ties between the United States and China could exacerbate geopolitical tensions between the two countries and make Russia increasingly important to the United States as a counterweight to China. This, in turn, could lead to a re-evaluation of the strengthening of the Russia-China axis, which is one of the most significant geopolitical threats the United States currently faces. Of course, Beijing will try to maintain strong ties with Moscow in the face of growing friction with Washington, but Moscow’s calculus could change as its economic challenges pile up and sanctions bite harder in the new environment.

Thus, while the pandemic certainly brings its fair share of challenges, it also offers opportunities for the United States to decrease tensions with Russia while also boosting its position relative to China. Moscow will remain a major challenge for Washington during and well after the coronavirus pandemic, but both sides have a chance to make short-term tactical gains. This, in turn, could lead to deeper strategic benefits for Washington down the line.

Eugene Chausovsky is a Nonresident Fellow with the Newlines Institute. Previously, he served as Senior Eurasia Analyst at Stratfor for 10 years. His work focuses on political, economic, and security issues pertaining to the former Soviet Union, Europe, and Latin America. He Tweets at @EugeneChausovsk.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of the Newlines Institute.