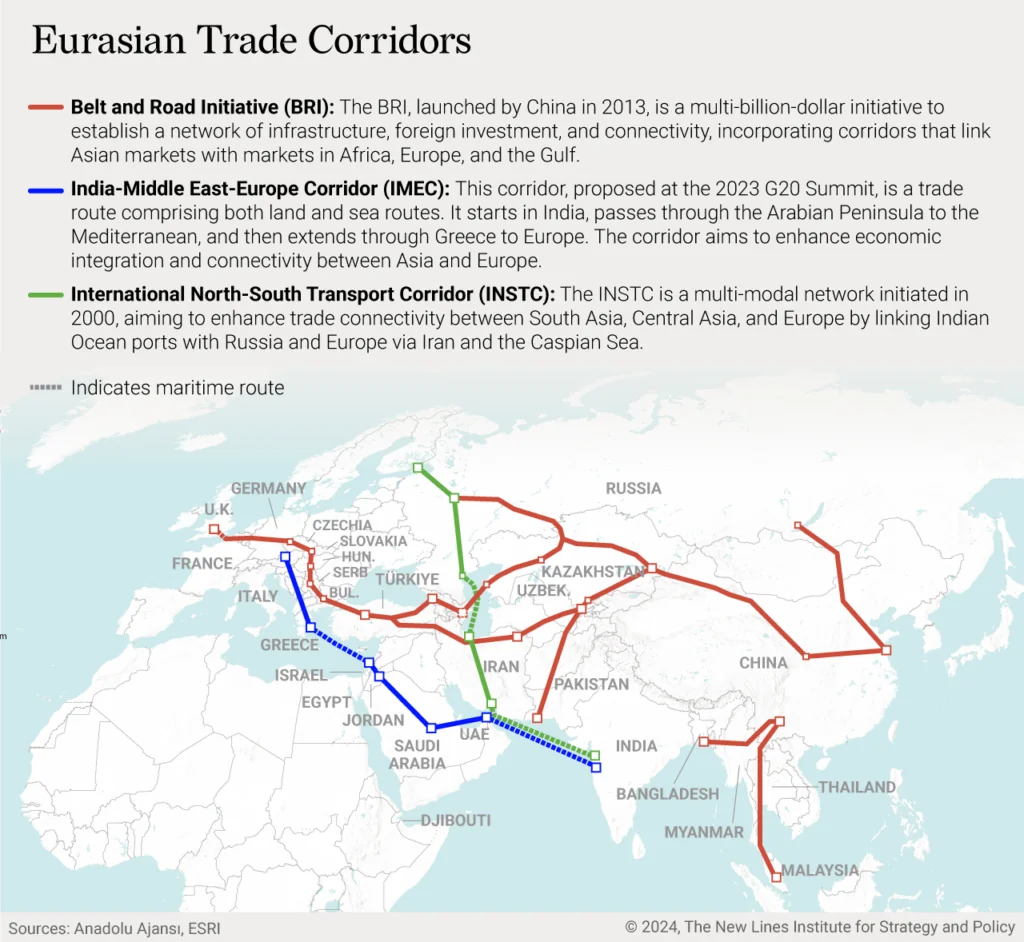

As China continues to prioritize the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) within its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) framework and its regional ambitions, it becomes evident that Beijing is committed to its strategic regional connectivity objectives as a rising great power. Consequently, U.S. foreign policy should place a higher priority on addressing China’s influence in regional connectivity projects. The U.S. should develop a containment-based strategy and design infrastructure and connectivity initiatives to serve as significant strategic tools in the Asia-Pacific region. Additionally, all developments related to the CPEC should be closely monitored, taking into account the evolving dynamics between China and Pakistan.

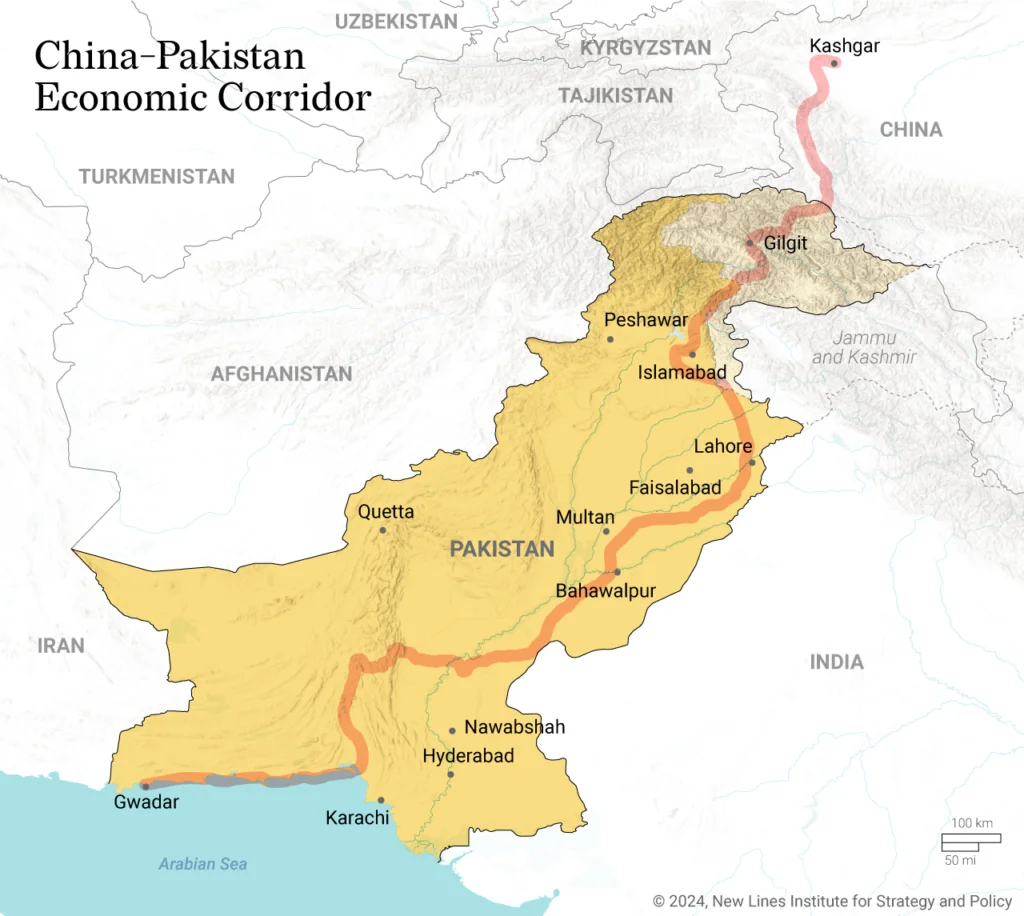

The CPEC, launched in 2015, represents the most expensive and ambitious connectivity initiative under China’s BRI, with an original estimated cost of $62 billion. The corridor spans approximately 3,000 kilometers (about 1,860 miles), commencing in China’s northwestern Xinjiang province and passing through Pakistani territory before reaching the Arabian Sea at the port city of Gwadar in Balochistan.

Over the past decade, the CPEC has come to mean different things for primary stakeholders China and Pakistan, as well as for the broader international community. For China, the project is a strategic move aimed at mitigating the “Malacca Dilemma,” a term describing the potential vulnerability posed by disruptions to China’s access to the Indian Ocean through the South China Sea in case of geopolitical tensions. “It also serves China as a critical conduit for reinforcing economic ties and expanding cooperation with the Persian Gulf region, an area where China’s economic engagement has intensified in recent years.”

Furthermore, as the flagship project of the BRI, the CPEC serves as a cornerstone of China’s international image, reflecting its dedication to global infrastructure development and elevating its prestige within its expansive investment portfolio. Beijing has strategically framed the CPEC as a symbol of China’s emergence as a major global player, showcasing its role in advancing globalization over the past two decades and sharing its sustained economic growth with the Global South.

Meanwhile, Pakistan sees the CPEC as a transformative initiative with the potential to revitalize its national economy, which is plagued by chronic financial instability and a significant shortfall in foreign investment. The host country also perceives the project as a vital geostrategic asset, offering Pakistan a competitive edge over its regional adversary, India.

Within the broader context of the international community, CPEC plays a pivotal role in China’s strategic posture in relation to the United States; connectivity projects are increasingly central to Beijing’s strategy to avoid encirclement by pro-Washington allies. These connectivity projects not only establish critical infrastructure and trade routes but also deepen economic dependency on Beijing, particularly through the accumulation of debt by participating countries. This economic leverage provides China with strategic influence over key regional actors, limiting their capacity to align with U.S.-led initiatives. By fostering both physical and financial ties, China is able to hedge against efforts by the U.S. and its allies to contain or encircle it, creating a buffer of indebted states reliant on Chinese investment.

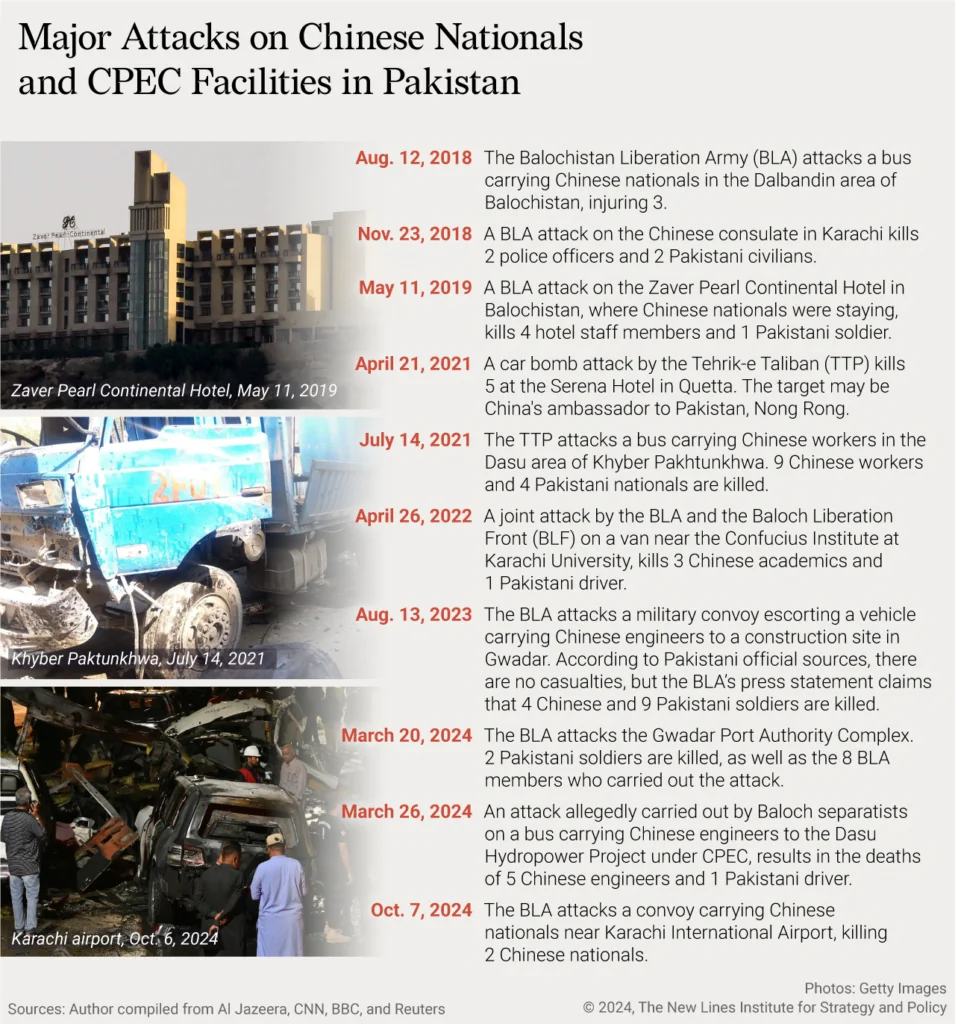

Despite the opportunities presented by CPEC, the project is not without significant risks. Persistent security challenges within Pakistan, coupled with financial constraints and a series of domestic political impediments, have tempered China’s enthusiasm for the project. These factors have compelled Beijing to adopt a more cautious approach. The growing anti-China sentiment in Pakistan’s Balochistan province, fueled by local grievances over the perceived exploitation of natural resources as in the case of Reko-Diq gold mines and environmental degradation related to Chinese-led projects, is exacerbated by the escalating activities of the Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA), alongside the destabilizing actions of militant groups such as ISIS-Khorasan (ISIS-K), Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), and Tehrik-i-Jihad Pakistan (TJP). ’

In light of Pakistan’s negotiations with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for additional bailout programs, the country’s mounting external debt has further intensified concerns about the CPEC’s sustainability. Moreover, alleged bureaucratic inefficiency and internal political strife fueled by regional rivalries have hindered the socioeconomic development of restive Balochistan, adding another layer of complexity to the situation.

The CPEC’s multifaceted nature and potential trajectory hold significant implications for U.S. foreign policy. As China deepens its economic and security ties with Pakistan through the project, it expands its influence in a region where U.S. interests, including regional stability, counterterrorism efforts, and the security of sea lanes, are at stake. If China were to gain unchecked dominance in South Asia, it could undermine U.S. alliances, weaken U.S. influence in global trade corridors, and potentially reshape the balance of power in favor of itself. Washington’s response to this risk should include the development of alternative connectivity projects within the framework of the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment, (PGII), close monitoring of the CPEC’s progress, and a focus on the socioeconomic and human rights issues in Balochistan, ensuring that these concerns are addressed in accordance with international norms and principles.

Main Challenges Ahead for CPEC

1. Security

Security concerns are a significant challenge to the implementation of CPEC infrastructure projects. Although attacks targeting Chinese workers, engineers, and project facilities are most concentrated in Pakistan’s southern and southwestern regions, particularly around Gwadar Port, incidents contributing to the overall sense of insecurity have occurred across the country. For example, during a series of attacks in March 2024, Chinese workers in Balochistan were targeted, and a suicide bomber rammed a convoy in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, killing five Chinese engineers. Attacks by the BLA and other groups in Balochistan are also hampering the construction and operation of CPEC infrastructure projects. Most recently, security concerns prompted a delay in the launch of a Chinese-funded airport in Balochistan.

These security threats, primarily attributed by Pakistani officials to the BLA, TTP, TJP, and ISIS-K, are largely fueled by ubiquitous anti-China sentiment in Balochistan. These groups perceive Chinese investments (the CPEC, in this case) as exploitative on the grounds that the Balochi people allegedly have not benefitted from socioeconomic development or improvement in their living conditions. In response, Beijing has demanded the Pakistani government conduct thorough investigations and increase security measures. Islamabad has repeatedly assured Beijing that attacks will not undermine Sino-Pakistani relations, emphasizing that bilateral ties remain resilient despite them. Also, Beijing has engaged with the Afghan Taliban to use it as a source of detente. The key motivation behind this move is that the Afghan Taliban, while primarily focused on Afghanistan, has historically had ties with militant groups like the TTP and TJP. These groups, although operating separately, share ideological commonalities and occasionally cooperate or overlap in activities. Another reason behind Beijing’s increasing engagement with Kabul, aside from this primary security issue, is its pursuit of a role as an influential actor in the region from which the U.S. has withdrawn, and as a foreign investor aiming for access to Afghanistan’s mineral resources.

Moreover, the issue of inequitable benefit distribution from the CPEC is generating significant socioeconomic concerns and engendering feelings of marginalization and exploitation among the ethnic Baloch in Balochistan. The BLA-led separatist movement has consequently targeted CPEC infrastructure, facilities, and personnel from both Pakistan and China. Additionally, protests organized by the Baloch Yakjehti Committee around Gwadar, addressing issues such as enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings, have led to security force interventions and the arrest of human rights activists like Sammi Deen Baloch.

To safeguard CPEC investments and protect Chinese personnel, Pakistan has established a security force with over 10,000 members under the 34th Light Infantry Division in 2016 and then added the 44th Light Infantry Division as the second tasked unit in 2020. However, if Beijing deems Islamabad’s efforts to secure the region as inadequate, it may request the deployment of Chinese security forces to protect CPEC assets – an option that Pakistani officials have consistently denied yet has been the subject of media discussion in recent years. Although fulfilling China’s request to bring its security forces to the CPEC region may backfire by increasing anti-Chinese sentiment, Beijing’s calculation may be to motivate Islamabad to take a more repressive position by tightening security measures.

Beyond the risk to China’s investments, the security threats emerging along the CPEC route, particularly in regions like Balochistan, threaten regional stability, a key U.S. concern. Unchecked militancy and unrest could destabilize Pakistan, complicating U.S. counterterrorism efforts and undermining its interests in South Asia. Therefore, the U.S. must focus on strengthening regional security cooperation and providing military aid and intelligence-sharing mechanisms to help Pakistan counter these threats. This would allow the U.S. to maintain a foothold in the region while reducing the likelihood that China could gain excessive security influence through its CPEC-related investments.

2. Financial Setbacks

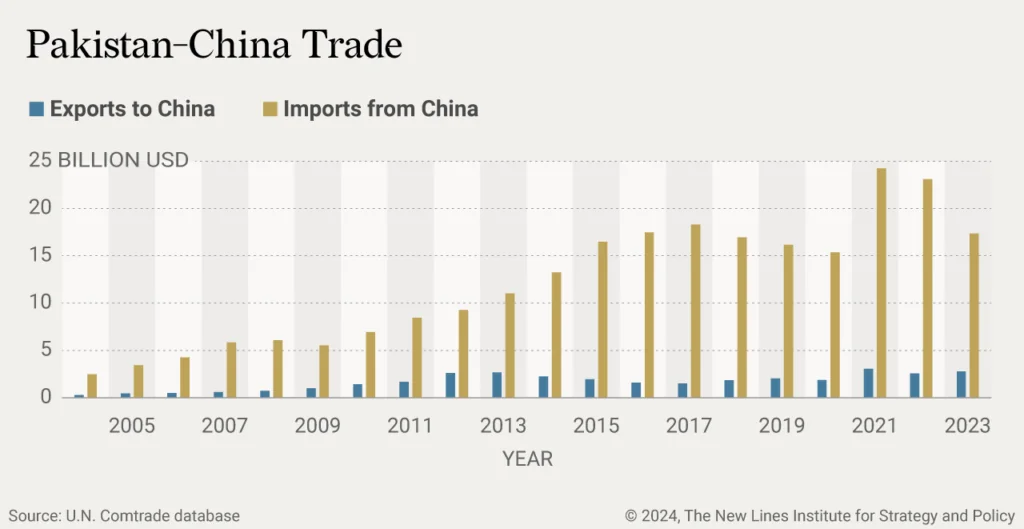

Another major impediment to the CPEC is the deepening economic crisis that has enveloped Pakistan. Balance of payments, persistent budget deficits, high inflation, and the depreciation of the rupee have contributed to a spiraling financial crisis. In July, following negotiations with the IMF, Pakistan secured a $7 billion loan. More recently, Pakistan obtained approval from its creditors – including Saudi Arabia, China, and the United Arab Emirates – for the rollover of $12 billion in external debt. Despite the IMF’s projections suggesting a potential decline in the debt-to-GDP ratio, which currently stands at approximately 70%, concerns remain given the country’s external debt of around $130 billion and the ongoing depreciation of the rupee against the U.S. dollar. Foreign exchange reserves amount to approximately $8 billion, which is adequate to cover only two months of imports. Also, the IMF warned that the increasing reliance on Chinese loans could be detrimental to the national economy.

In response to the conditions stipulated in the Stand-By Arrangements with the IMF, measures have been implemented to restore fiscal balance and stability, including substantial increases in taxation. Specifically, direct taxes such as income tax and corporate income tax, have been raised by 48% and indirect taxes, collected from sales, by 35%. These measures are likely to have a significant impact on public purchasing power and are a source of considerable public discontent.

Given the current financial context, projecting an optimistic future for the CPEC is hard. This project, being the most expensive within the BRI, relies on Chinese funding to complete a complex infrastructure network including highways, tunnels, railways, ports, and other complementary parts. However, China has shown reluctance to provide new loans for infrastructure modernization within Pakistan or for the construction of new highways and railways. Consequently, Pakistan’s Executive Committee of the National Economic Council has deferred approval of the $6.7 billion required for the ML-1 railway project – an essential component of the CPEC connecting Peshawar and Karachi. Instead, a phased approach has been adopted, with approval granted only for the initial phase requiring $1.1 billion. The initial target date for completing the entire ML-1 project had been June 2023, but this deadline was not met. This example underscores the constraints the current financial conditions impose on the completion of such projects.

Moreover, the thought that CPEC projects would generate 2.2 million jobs by 2030 is currently far from reality, with only approximately 236,000 jobs created to date, of which 155,000 are held by Pakistanis. Additionally, the financial challenges are contributing to a decline in business and investment confidence within the country. According to Gallup’s Business Confidence Index survey for the second quarter of 2024, perceptions of the current business environment, future business prospects, and the country’s overall direction have deteriorated compared to the first quarter. Specifically, 55% of businesses have reported a worsening of the current conditions, the index shows. This decline in confidence adversely impacts the potential to attract domestic investment into the special economic zones planned around Gwadar as part of the CPEC.

The financial burden imposed on Pakistan by CPEC projects – especially through Chinese loan indebtedness – risks pushing the country into a debt trap, wherein high levels of debt repayment obligations stipulated by the creditor could lead to economic instability and reduce a debtor’s financial autonomy. Such instability would not only undermine Pakistan’s economic independence but also drive it further into Beijing’s sphere of influence, reducing U.S. leverage in the region. To counter this, the U.S. should provide economic alternatives, such as debt restructuring support or investments in sustainable, high-return sectors like renewable energy. By offering financial solutions that promote long-term growth and stability, the U.S. can help Pakistan avoid economic overreliance on China.

3. Domestic Factors

Domestic political and social challenges pose an additional impediment to the CPEC. The evolving political landscape, characterized by shifting governments and coalitions, has led to differing views of the project among Pakistan’s leaders. For instance, while the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) government under Nawaz Sharif made initial strides toward Chinese contracts for investments in the project and some progress on building it in 2015, the subsequent Pakistani Tehreek-e-Insaf government led by Imran Khan encountered various issues, including project reassessments and delays, primarily due to transparency concerns. The PML-N government faced allegations of corruption and bribery, with claims that CPEC project tenders were awarded unfairly to Chinese firms, often accompanied by tax breaks. After Saudi Arabia declined to provide favorable bailout support, Khan’s government adjusted its stance on the project, establishing the CPEC Authority via ordinance to expedite project implementation. This response underscores a lack of domestic political consensus and shifting perceptions regarding the alignment of the CPEC with Pakistan’s national interests, revealing that support for the project by governments may sometimes be driven more by financial necessities than by genuine enthusiasm.

The socioeconomic issues arising from political disputes and the Baloch population’s doubts regarding the advantages of the CPEC represent major obstacles to the project’s progress. Considering the assertions that the media narrative in both Pakistan and China and the information flow around the project are swiftly and reactively managed to be pro-CPEC, political disagreements surrounding it may not be widely known to the general public. However, the contrasting approaches taken by the Khan and Sharif governments highlight this divide.

The domestic political and social challenges surrounding the CPEC, particularly the lack of government consensus and transparency concerns, pose a significant threat to the project’s long-term success. These difficulties provide a unique opportunity for the U.S. to engage diplomatically. By emphasizing transparency and anticorruption measures and public accountability, the U.S. can position itself as an advocate for good governance in Pakistan. This approach would not only contrast with China’s model of opaque deals but also resonate with the segments of Pakistani society and political factions skeptical of the CPEC’s alignment with national interests. Furthermore, the U.S. can leverage these domestic tensions to build diplomatic capital by offering assistance in institutional capacity-building, helping Pakistan create more transparent regulatory frameworks, and fostering dialogue around inclusive economic development.

By aligning with local concerns and advocating for greater domestic accountability, Washington could strengthen ties with Pakistan while diplomatically highlighting the risks of overreliance on China. This would not only provide an alternative narrative to China’s growing influence but also allow the U.S. to expand its diplomatic engagement in a way that addresses Pakistan’s internal governance challenges while indirectly countering Beijing’s hold on the country.

How Could China Progress on CPEC?

Given the geostrategic importance and global significance of the CPEC, it is improbable that China would fully abandon the project or adopt an aggressive stance that disregards pressing issues in favor of simply completing the infrastructure. A complete withdrawal from the project is contrary to China’s geopolitical interests associated with the CPEC, such as escaping the Malacca Dilemma and gaining direct access to Gulf markets. Moreover, withdrawal from the CPEC would damage China’s reputation in developing countries as it symbolizes the value of the BRI as a whole. On the other hand, the possibility that Beijing would aggressively pursue the project is equally unlikely, as China cannot ignore continued security risks to Chinese nationals and the infrastructural projects themselves. Instead, in light of ongoing the security concerns, Pakistan’s financial setbacks, and domestic challenges, China is likely to pursue a strategy of cautious, moderate progress. This approach aligns with a broader shift in the BRI, moving from an initial focus on large-scale projects to a more strategic, phased, and effective method.

Regarding security policy, significant issues in Pakistan have not been resolved to Beijing’s satisfaction. Tackling the strong anti-China sentiment among the Baloch population is particularly difficult. The Pakistani security forces, primarily made up of civilian police, have struggled due to training gaps and coordination challenges, proving insufficient for the task of tackling the insurgency and assuaging China’s concerns. Consequently, Beijing may increasingly demand the deployment of specialized units from the People’s Liberation Army to Gwadar. Following the assassination of three Chinese teachers by the BLA in Karachi University in 2022, Islamabad allowed Chinese investigators to enter the country for the first time. Continued attacks could lead to increased pressure on Islamabad, highlighting the need for effective security measures.

China will also likely pursue a financial recalibration strategy. Given Pakistan’s significant external debt burden and engagement with the IMF, China will adopt a dual approach. An open-door policy for new stakeholders in CPEC projects has been in place for several years, with recent agreements with Gulf countries, including Saudi Arabia and the UAE, for investments exceeding $28 billion reflecting this strategy. Pakistan has established the Special Investment Facilitation Council to facilitate such investments. Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit to Riyadh in December 2023 and increased economic engagement with the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) have accelerated this investment trend. Additionally, the evaluation of the ML-1 railway network in separate phases rather than a single bid underscores China’s strategic shift from a holistic approach to CPEC projects to a more incremental one, mirroring its changing approach to other BRI projects in general. This phased approach aims to mitigate financial constraints by progressing in smaller, more manageable steps.

Diplomatically, China’s CPEC strategy will focus on three primary objectives. First, it will exert pressure on Islamabad to address domestic issues, including the Baloch separatist movement. This may involve deviating from China’s traditional noninterference principle to ensure that CPEC benefits are equitably distributed and aligned with welfare needs. In practice, this could mean encouraging Pakistan to allocate a greater share of CPEC investments to Balochistan by funding local infrastructure projects, revising local tax policies in a fairer way, creating job opportunities, and improving access to essential services like healthcare and education. Despite China’s initiatives near Gwardar such as the China-Pakistan Friendship Hospital and a desalination facility, combating anti-China sentiment will require significant effort from Pakistan, which must address these issues through fair social welfare policies such as equitable distribution of resources, targeted investments in education and healthcare for underserved communities, fair taxation policies, and job creation initiatives specifically aimed at reducing unemployment.

Secondly, China will seek pragmatic engagement with the Afghan Taliban to preempt disruptive actions by affiliated groups like the TTP and TJP. This includes demonstrating goodwill in critical sectors such as energy and infrastructure, integrating the Taliban into the BRI, securing mining rights, and exerting diplomatic pressure on the Pakistani Taliban to prevent attacks on CPEC investments. This approach is likely to prompt concerns in the U.S., as China’s involvement bolsters Beijing’s role as a power broker in Afghanistan and also challenges the U.S. by creating an alternative model of influence over regional militant activities. Washington may not immediately react to Beijing’s growing engagement with Kabul as it must first ascertain the limits and scope of China’s diplomatic communication with Afghan leaders. It is highly probable that the primary factor driving China’s engagement is, as previously indicated, a pursuit of detente in security matters coupled with an ambition to expand economic cooperation in order to access Afghanistan’s mineral wealth. The U.S. response depends ultimately on these factors.

China also likely will enhance diplomatic relations with the GCC to attract new investors for CPEC, addressing financial challenges and reducing its investment burden by engaging alternative partners. China’s diplomatic strategy will involve continuous dialogue to address security concerns, especially regarding allegations of attacks originating from Afghan territory and pressure on Islamabad to improve transparency and address domestic issues. Despite potential challenges, China will seek to ensure the CPEC maintains its intended global image and prestige.

Lastly, managing the media narrative around the CPEC will be a key element of China’s strategy. Due to the symbolic significance of the project within the broader BRI framework, China will seek to avoid any narrative of failure that could harm its reputation. Maintaining a positive portrayal of the CPEC’s progress is a priority for both China and Pakistan. To achieve this, the countries are planning a joint effort called the China-Pakistan Information Corridor to manage information and media narratives, hoping to ensure the project continues to be perceived positively, a crucial goal for China’s global image and the prestige of the BRI.

The U.S. Response

In light of China’s multifaceted strategy regarding the CPEC and the security, financial, and domestic problems influencing this strategy the following recommendations are proposed for formulating a U.S. approach:

1. Monitoring the CPEC’s Progress

It is crucial for the U.S. to implement a comprehensive framework for monitoring the CPEC. While current U.S. initiatives, such as diplomatic engagement and economic aid, aim to counterbalance China’s influence, a new comprehensive framework would differ by focusing on real-time, multidomain intelligence-gathering, economic impact assessments, and local partnerships. This framework would track the project’s progress, assess its impact on U.S. allies in the region, and identify opportunities to counter China’s strategic foothold in South Asia. Unlike the Blue Dot Network, which promotes infrastructure development through transparent, high-quality standards, this framework would center on preventing the CPEC from becoming a tool for expanding Chinese influence and economic dominance. This framework should encompass assessing the current phase of each infrastructure investment under the CPEC, evaluating the terms of the loan packages provided by China for financing, and comparing sub-projects with their respective deadlines.

Additionally, it is important to analyze the nature of China’s diplomatic engagement with the Afghan Taliban, including any transactional elements in relations with Kabul to alleviate the security-related challenges of the CPEC. Furthermore, monitoring should examine whether the GCC investment interest translates into tangible investment actions, such as Saudi Arabia’s stated interest in a $10 billion refinery project in Gwadar. Finally, scrutiny should be applied to ensure that Pakistan’s adherence to IMF loan conditions focuses on addressing structural issues through sustainable policies rather than merely financing CPEC projects.

2. Focusing on Interconnectivity and Trade Corridors

An essential component of the U.S. strategy regarding the CPEC should be the development of a robust connectivity strategy that recognizes the increasing significance of trade corridors in global geopolitics. The PGII stands out as a pivotal initiative, providing a framework for economic cooperation and fostering long-term dialogue. This is another way of diplomatic business that strengthens multilateralism.

Accordingly, Washington’s approach to connectivity must prioritize inclusivity, crafting an appeal capable of attracting regional states that currently maintain strong ties with China. For instance, the deepening relationship between China and Pakistan through CPEC could strain U.S.-Pakistani relations, driving Islamabad closer to Beijing. To counter this, the U.S. should deploy connectivity projects that offer viable alternatives to Pakistan. A project like a U.S.-Pakistan renewable energy corridor – facilitating the development of solar and wind farms or smart city development using eco-friendly infrastructure – could address Pakistan’s energy needs, offering sustainable solutions that the CPEC has yet to prioritize. Additionally, U.S.-backed investments in digital infrastructure, including fiber optic networks and 5G, would position the U.S. as a technology partner, further distinguishing it from the CPEC’s heavy emphasis on traditional infrastructure. In fact, one of the investment lines that Pakistan could not negotiate with China within the scope of the CPEC’s upgrade was related to information technology and connected technology infrastructure. Therefore, in the connectivity and investment strategy to be developed by the U.S., the appeal of such areas in the Pakistani perspective would be an important advantage compared to the conventional investments in CPEC’s infrastructure.

India’s involvement in the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor illustrates this dynamic; while India has benefited from substantial U.S. support for the project, it has simultaneously maintained strategic engagements with Iran through the Chabahar Port and the International North-South Transport Corridor. Despite facing sanctions warnings from the U.S., India has continued its engagement with Iran, balancing multiple alliances.

Conversely, without a clear connectivity framework from the U.S., Pakistan may feel compelled to rely exclusively on China’s proposals, further entrenching the China-Pakistan relationship through the CPEC. To mitigate this risk, Washington must ensure that Pakistan is actively included in regional connectivity networks and is aware of viable alternatives to Chinese initiatives such as U.S.-led infrastructure projects under the PGII. These could include initiatives like the development of renewable energy corridors, digital infrastructure partnerships in fiber optics and 5G, or investments in transportation networks linking Pakistan to Central Asia. Additionally, the U.S. could collaborate with multilateral development banks to offer financing options that prioritize sustainability and transparency, providing attractive, long-term alternatives to Chinese loans under the BRI.

3. Countering Pro-CPEC Propaganda

China’s tight control over the media narrative surrounding the CPEC has enabled it to systematically construct and promote a public perception of the project as promising and inevitable. While alternative information sources help counter the disinformation generated by this narrative, it is important to acknowledge that this message still resonates with certain audiences, some of which might be among the participant nations of the BRI. Notably, China and Pakistan are working on an initiative called the China-Pakistan Information Corridor to institutionalize and further tighten control over the CPEC narrative. Through this, both countries aim to communicate that the significant obstacles facing the project will not impede its progress and that the project will continue at all costs. Given the strategic importance of the BRI for China, and the critical role that the CPEC plays within it, Beijing is committed to perpetuating a strong image of the project.

In response, the U.S. strategy should focus on countering this blatantly pro-CPEC narrative by promoting platforms that expose the true challenges of the project – particularly the risks of dependency it may create and the difficulties it faces. Also, the U.S. should prioritize that acute socioeconomic problems in Balochistan are widely reflected in media so that the Chinese model of bringing prosperity through economic engagement without properly addressing human rights and social welfare needs has no appeal in the global public opinion. It is crucial to understand that CPEC is not just a symbol of actual progress for Beijing but also a potent media tool. By developing a counternarrative that emphasizes the substantial challenges CPEC encounters, especially in terms of security and financial setbacks, rather than solely focusing on its potential, the U.S. can contribute to a more realistic and balanced understanding of the project.