As India and China continue militarizing the border region along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) and the status quo deepens, it risks an all-out armed conflict with India facing the strains of a two-front situation. The continuing border standoff keeps India off-balance and occupied on its Himalayan border while China expands its engagement with other South Asian neighbors. The United States’ interest lies in avoiding a prospect of a limited or full-scale India-China armed conflict.

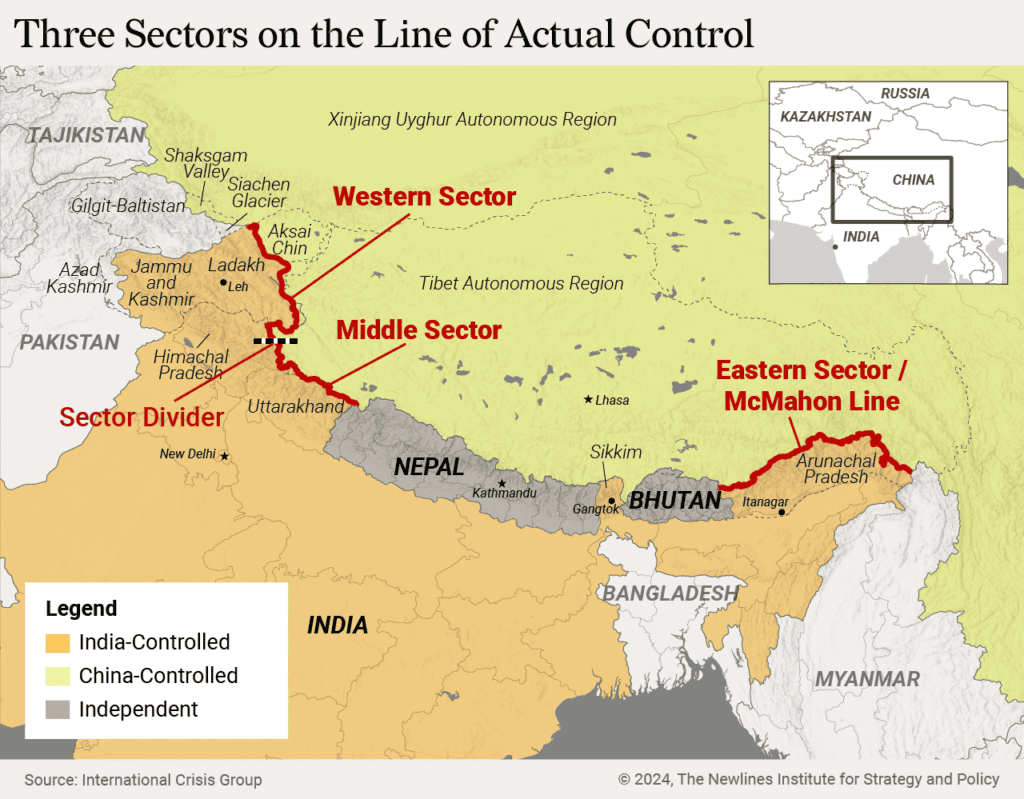

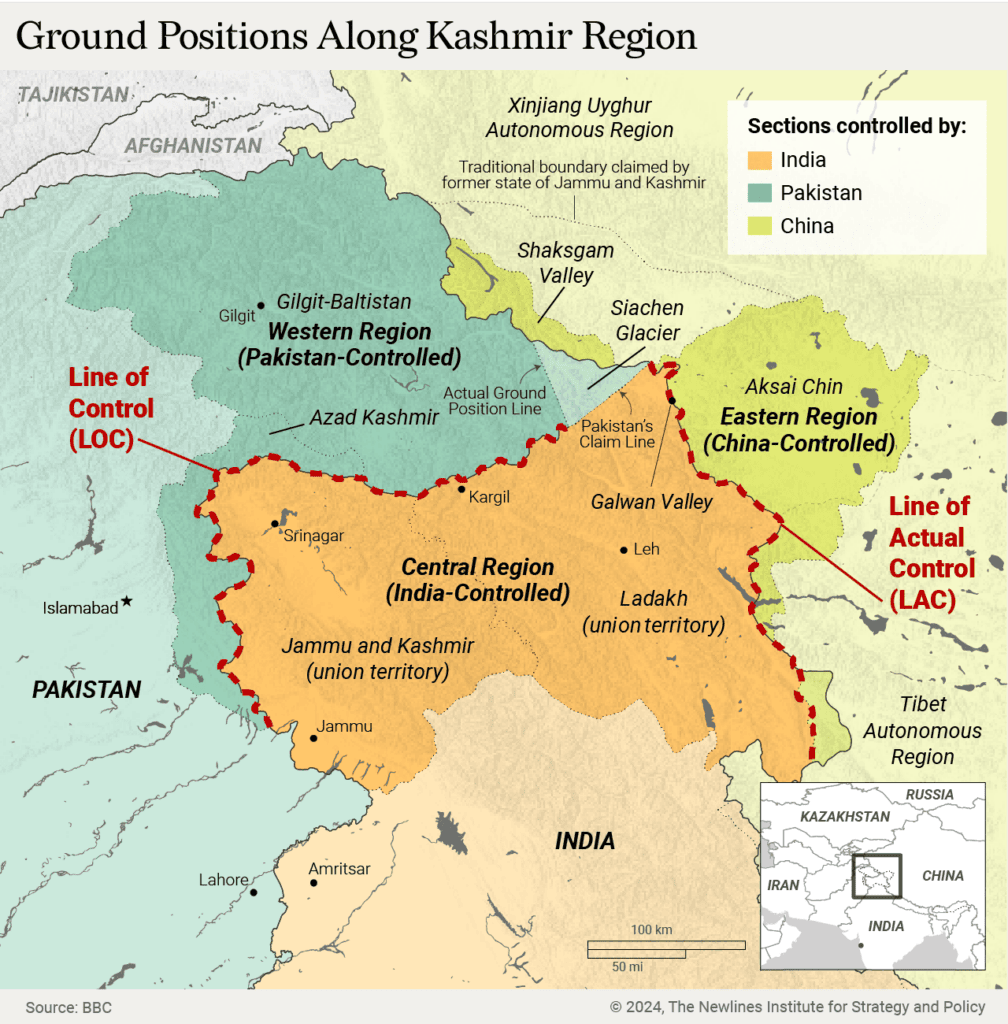

The military reassertion of competing claims by China and India on the LAC has revived one of the world’s longest unsettled boundary disputes. In May-June 2020, bilateral ties between them plunged to their lowest in decades after a violent clash between their soldiers. Military tensions continue along the eastern sector (Arunachal Pradesh) and the western sector (eastern Ladakh) of the more than 2,100 miles (3,380 kilometers) of contested LAC separating the two countries. In early September 2024, China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) troops reportedly intruded up to 37 miles into the Indian-claimed area in Arunachal Pradesh, showcasing the continued border standoff between the two countries. (However, this assessment only focuses on the standoff in the western sector.)

The border standoff continues even after nearly four years. Limited de-escalation through the establishment of buffer zones – marked disengagement areas – has been achieved. Yet tensions persist, with both sides building up their military presences in the area through infrastructure upgrades, increasing numbers of troops, and the deployment of new weapons systems. Even as the current deadlock is being addressed, conditions for a potential limited border war remain.

To maintain border stability and regional security, Beijing and New Delhi need to guard against the potential spiral of the ongoing standoff. The intense Indo-Chinese tensions along the border complicates regional geopolitics. As India prioritizes border stability in Himalayas, its attention to and preparedness across the Indo-Pacific is waning. This directly impinges on the U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy, where India is viewed as a net security provider across the Indian Ocean region. China’s changing external outlook, particularly toward its border disputes, has been registered by a “nonaligned” and “neutral” India, but it still needs to appreciate how the continued border standoff has become a drain on India’s limited defense resources.

For both Beijing and New Delhi, national prestige and the potential loss of territory is at stake. Hence, it is crucial for them to seek ways to stabilize the current crisis through backchannel diplomacy. Washington can play a role by communicating the risks of a border war to Beijing directly along with the assurance that it will continue to take policy steps to avert one by sharing technical intelligence and publicly bringing attention to the emerging threat.

Ground Survey: State of the Standoff

The fallout of the 2020 escalation, and subsequent political and military moves by both sides, have undermined the 1993 and 1996 bilateral agreements that ostensibly govern military conduct along the LAC. The 1993 agreement, “Maintenance of Peace and Tranquility along the Line of Actual Control in the Sino-Indian Border,” mandated that both sides keep troops to “minimum levels” and give prior notification to the other country of “military exercises of specified levels” near the LAC. Similarly, the 1996 agreement on confidence-building measures in the military field along the LAC mandated disclosures of troop exercises and invitations to observers from their adversaries into their territory. Moreover, it also identified the types of military equipment for reduction: tanks, infantry vehicles, howitzers with 75 mm or higher caliber, mortars with 120 mm or higher caliber, surface-to-surface missiles, and surface-to-air missiles. These agreements have been flouted during the past four years, at least in the western sector of the LAC, as both sides have deployed tanks, infantry vehicles, missiles, and air defense systems, among other weapons prohibited by the agreements.

This context now hangs over the bilateral engagement processes. The countries remain engaged via military, diplomatic and occasional political channels. Progress toward a resolution of their differences, however, has been slow. The outcome is localized and episodic. The buffer zones at Galwan River Valley and Pangong Tso Lake have only addressed the tactical forward military presence, not the larger strategic standoff.

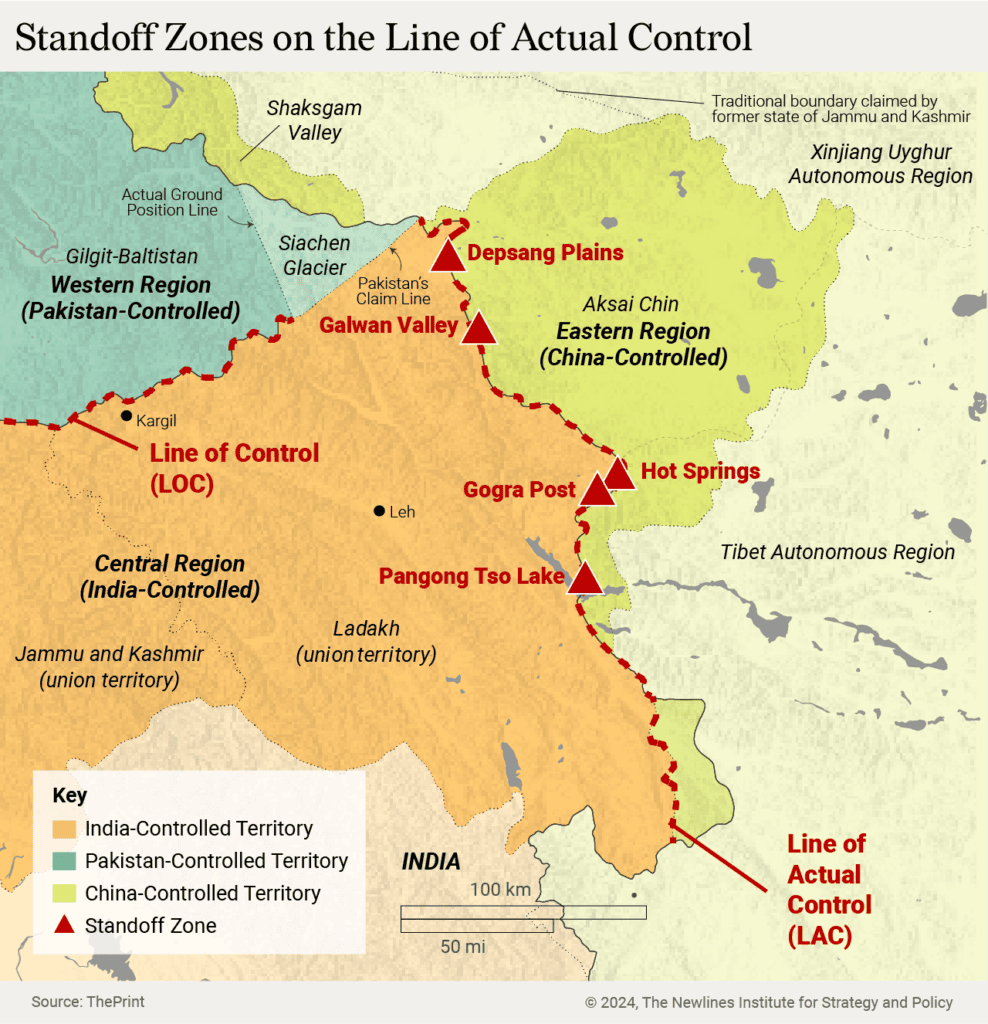

Border standoffs are primarily about geography and tactics. In April 2020, the PLA expanded its patrolling to five key nodes in the western sector of the LAC: the Galwan River Valley, Gogra Post, Pangong Tso Lake, Hot Springs, and Depsang Plains in the Daulat Beg Oldi (DBO) sector. The last site is known to the Indian military as “sub-sector north” and is located five miles south of the Karakoram Pass, which separates Xinjiang from Ladakh. The wider western sector of the LAC is the most contested part of the disputed boundary between the two countries. Both sides lay claim to territory citing their own maps, specify their own claim lines, and send patrols to indicate their claims accordingly. In 2020, Chinese units pushed farther west of their claim line at two points: Pangong Tso Lake and the Galwan River at its confluence with the Shyok River. New Delhi claimed that PLA units moved up to 11 miles inside the Indian-claimed line.

On June 15 of that same year, a physical skirmish led to the first border dispute-related deaths of soldiers from both sides (20 Indian troops and four Chinese soldiers). This theaterwide standoff established a new normal: Rules and norms governing military conduct along the LAC no longer keep the peace.

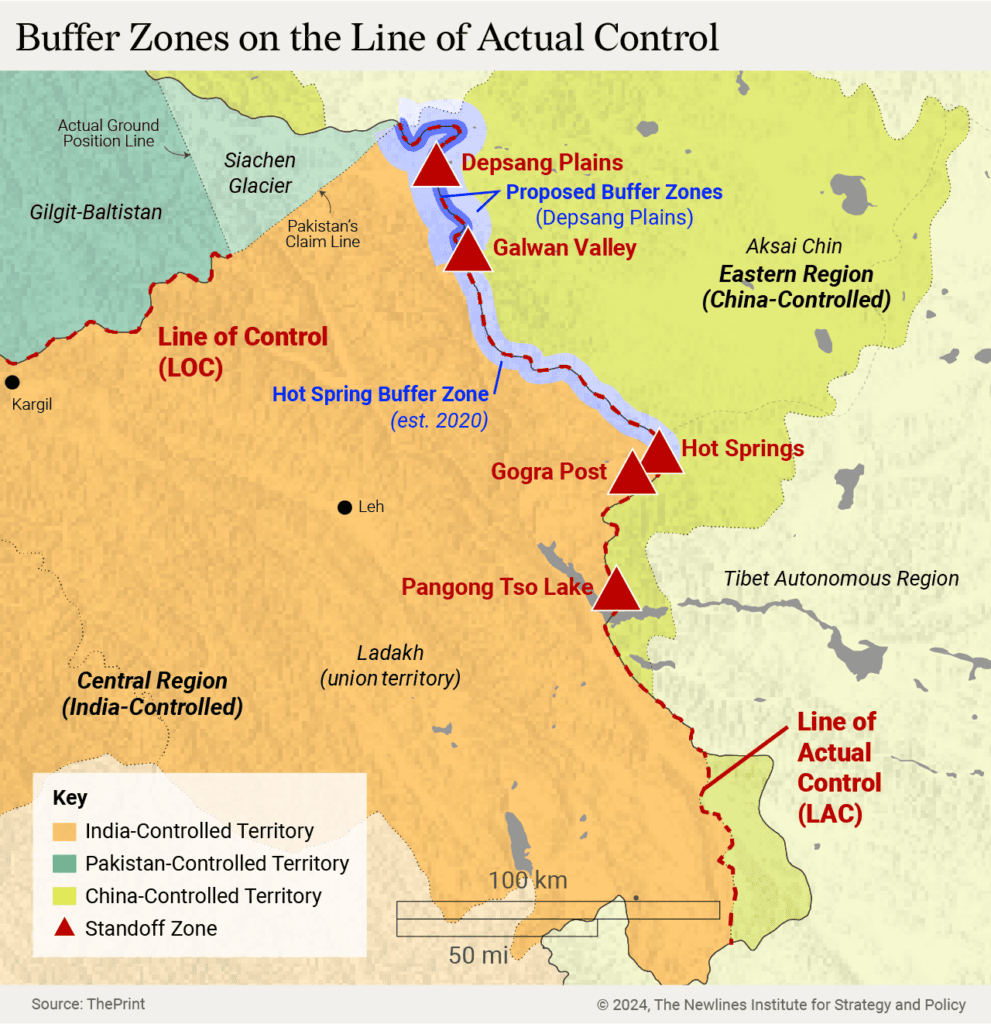

In the immediate aftermath of that clash, local military commanders from PLA’s South Xinjiang Military District and the Indian Army’s 14th Corps began de-escalation talks. Since September 2020, over 21 rounds of talks between the two militaries have taken place. In parallel, diplomatic talks on border affairs have also been taking place. At the end of the latest round, in August 2024, both sides reported a “forward-looking exchange” to “narrow down differences.” These talks have led to the establishment of buffer zones by pulling back troops, moving equipment and weapons systems, and destroying infrastructure at Patrol Point 14 (or PP 14) in the Galwan River Valley, PP 15 in Hot Springs, and PP 17A near the Gogra Post. In these locations, buffer zones physically separate troops from both sides. In the Galwan River Valley, the buffer zone extends a mile on each side from the site of the clash, thus effectively near the two-mile-long buffer zone. Only 30 troops from each side are stationed outside the buffer zone, and another 50 are less than a mile away.

At Pangong Tso Lake, after an initial Chinese ingress on the northern side, India seized additional peaks and passes along the southern side in the Kailash range, threatening Chinese forces below. India used its newfound leverage to its advantage in negotiations about which side would pull back first. After a nine-month faceoff, both sides agreed to create a five-mile buffer zone between geological features of the lake termed Fingers 3 and 8, and pull troops and equipment back from the north and south banks of the lake and the Kailash range while dismantling military support facilities. This was completed in four steps over a month, with on-ground verification after each step.

Now, disagreements over territory persist at Depsang and Demchock. Military postures of both sides have hardened, and each has deployed 50,000 to 60,000 troops in the region. The Indian army has reoriented the mission of one of its strike corps from an infantry unit focused on Pakistan and its Line of Control to a mountain-focused corps and redeployed it toward the LAC in the Ladakh region. In 2021, India deployed 50,000 new troops along its border with China; 20,000 of those were deployed in Ladakh. In March 2024, New Delhi’s defense planners redirected 10,000 additional troops from the Pakistani border to beef up India’s presence along the China border. Meanwhile, a 2024 study by the Strategic Studies Institute of the U.S. Army War College assessed that nearly 20,000 PLA troops are deployed in the Aksai Chin area. Indian media reports have consistently estimated that 50,000-60,000 Chinese troops are deployed in Ladakh. A 2022 report claimed that China has constructed new facilities to support the deployment of nearly 120,000 troops within about 60 miles of the LAC. Conversely, the Indian military has built support facilities to house nearly 55,000 troops in Ladakh. This expansive military build-up changes the nature of the ongoing standoff and increases the risk of a limited armed conflict. Both sides can now mobilize additional ground forces to achieve tactical and operational objectives in the western theater before political and diplomatic interventions can be made.

Most significantly, both sides have deployed new offensive weapons systems along the border. PLA has deployed new rocket launchers, air defense systems, S-400 anti-aircraft systems on its air bases in Xinjiang and Tibet. Similarly, in October 2023, Indian army also deployed an S-400 air defense battery on the border with China. Both the PLA and Indian air forces maintain fighter jets on the frontlines. Besides, both sides continue to conduct military exercises both for the purposes of training their own troops and for signaling preparedness levels to the other side. These exercises enhance troop familiarity with the high-altitude rugged terrain and demonstrate the ability to quickly respond to any surprise moves by the other side. In June 2022, during an air defense exercise by Chinese forces, its jets flew over the flash point of the LAC in breach of a bilateral agreement that fighter jets should not fly within six miles of the LAC, prompting Indian forces to scramble jets in response.

These hardened military postures have been supported by continuous infrastructure buildup by both sides along the LAC, particularly in the Ladakh sector, that will enable quick mobility of combat units and equipment. China has constructed heliports and forward bases in the Aksai Chin region, opposite the Indian presence in the DBO sector. This allows for rapid deployment of troops and faster movement of reinforcements in case of crisis escalation. Similarly, India is upgrading air bases in the Ladakh sector to boost its presence. Meanwhile, satellite imagery depicts construction of a division-level headquarters by the PLA at Pangong Tso Lake, comprising barracks and new support buildings such as weapons shelters. It indicates that the PLA intends to maintain a permanent presence in the region as continued military deployments force India to prioritize land-border security and sidetrack its shift toward the emerging competition across Indo-Pacific. In the same area, India is improving its road infrastructure for mobility and advanced landing through construction of blacktop roads on the northern side of Pangong Tso Lake. China, however, is constructing a bridge across the lake connecting both southern and northern banks.

Buffer Zones Are Necessary for Border Peace

In the eastern Ladakh standoff, buffer zones have emerged as a new de-escalation model. But reaching a consensus on modalities of a buffer zone has taken a drawn-out negotiation process. The zone’s parameters also reflect each side’s relative bargaining position in that particular standoff location. For instance, it took 16 rounds of corps commander-level talks to reach consensus on establishing the first buffer zone in Hot Springs. This buffer zone has been sustained for over a year now. Both sides are adhering to their new positions and have not undertaken new infrastructure construction or directed troops to patrol inside the agreed limits of the buffer zone. It indicates that when India and China’s political leaders and military commanders reach consensus, buffer zones offer a practical pathway for resolving the immediate standoff.

At Depsang, China has proposed a buffer zone about 9 to 12 miles long, while India is pushing for one significantly smaller. India asserts that China’s proposed zone sits too deep inside India’s own claim line, thus effectively barring Indian troops from areas they had patrolled before 2020 ̶ depriving it of access to territory in which it once had a presence. The politics of buffer zones make modalities and sizes crucial issues for both sides. Each wants to make maximum gains while offering minimum concessions, lest those concessions be construed as ceding territory.

New buffer zones have changed the nature of the military presence in the western sector of the LAC. Limits on where both sides could send patrols have been redefined. Now troops from both armies are barred from patrolling inside the buffer zones – a measure that creates physical separation between the two militaries. In the zones at Hot Springs and Galwan River Valley, it has meant that the Indian army is unable to patrol up to the Indian-claimed LAC. Similarly, both sides would expect the other side to take advantage of moratoriums in patrolling and prepare for a tactical surprise. However, such actions can be mitigated through continuous satellite surveillance and patrols with remotely piloted aerial vehicles to the outer limits of the zones.

Without the buffer zones, continued military buildup and infrastructure development increase the odds of a wider armed confrontation between two sides. The next border clash between the PLA and the Indian army would likely be more violent, considering that the bilateral agreements governing military conduct along the LAC have been violated already. The upgrades to roads and bases and the deployment of additional troops have primed both sides for a border war. This is further complicated by regular military exercises and demonstrations of support capabilities that enable both sides to shorten mobilization times for reinforcements to border areas in the event of an armed clash.

For now, both sides are advancing their territorial claims along the contested LAC by practicing various degrees of offensive deterrence. The force buildup and construction of support infrastructure indicates that both sides are ready to sustain long-term deployments. The growing scale and expansive scope of both India’s and China’s military presence indicate a preference to project capability for rapid engagement in offensive operations if one country’s presence is contested by the other side. Both intend to maintain forward deployments and want the other side to recognize that and make concessions first in the ongoing military and diplomatic talks. China had a first-mover advantage in the early stages of discussions. Now, India has also built up considerable infrastructure, enhanced the number of troops deployed along the border, and bolstered support facilities. Both sides are attempting to exploit gaps in the other’s posture, and seek asymmetric advantage, which can increase the risk of an armed confrontation.

Policy Recommendations

As both sides build up their forces and infrastructure along the LAC, the risks of a miscalculation or misstep spiraling into a wider military confrontation increase. To lessen the chances of this happening, the parties involved and those with interests in the region should consider the following actions:

- Diplomatic engagement: Both sides need to prioritize security and stability along the contested LAC instead of any strategic surprises to gain further territory. Backchannel diplomacy, particularly Track 2 dialogues, can help India and China change their priorities, but it essentially requires recognizing the drivers of the current standoff: Beijing needs to acknowledge that New Delhi’s perception of the Ladakh and Aksai Chin region has undergone a shift in recent years under a nationalistic Bharatiya Janta Party-led government, and New Delhi should consider that its domestic actions to change the status of the Ladakh region triggered China’s westward push beyond its 1959 claim line. The nationalistic leaders in Beijing and New Delhi are advancing their nation’s respective claims through both rhetoric and power projection.

- Off-ramp measures: In the interim, both sides should consider joint military and diplomatic talks to complement corps commander-level talks; regular communication between theater commanders on emerging postures; joint surveys of both sides’ ground positions in the standoff zones; and periodic foreign minister-level talks to review progress on the border issues. The goal of these measures is to turn the temporary disengagement that buffer zones enable into sustainable border peace without undermining historical claims of both sides on the LAC. These measures insulate against domestic politics, particularly in India, where concessions on establishing buffer zones can be interpreted as accepting the Chinese presence on territory previously patrolled by India.

- U.S. preparation: For the international community, particularly the United States, it is crucial that India and China set up guardrails around their border tensions. It is critical that U.S. policymakers across different departments and agencies (Defense, State, and the intelligence community) closely monitor developments along India-China border, particularly, the western sector in eastern Ladakh. The U.S. can undertake proactive policy planning both with India and among agencies. For the former, U.S. can participate in wargames with India to gauge Indian military preparedness in the event of India-China border war. Tabletop exercises with Indian defense planners will inform both Indian policymaking and U.S. planning. Secondly, the U.S. can a simulate a limited border conflict between India and China to gauge how it might impact the broader military posture across the Indo-Pacific and anticipate disruptions to global supply chains.

Escalation of the current standoff or a renewed military crisis will have a direct impact on the broader Indo-Pacific strategy, of which India is a pillar. Even a limited armed conflict between India and China would draw New Delhi’s strategic focus away from the Indo-Pacific to its Himalayan land borders. It could be in Beijing’s broader regional interest to keep India off-balance through aggressive military buildup and forward deployments along the LAC, but that strategy runs the risk of undermining wider security and stability in the region. Here, Washington can play a crucial role through its expansive geospatial capabilities to keep a close eye on the military postures of both sides, their infrastructure development, and the construction of new facilities. Timely information-sharing is crucial for assuring India that if it agrees to set up wider buffer zones, it can rely on additional verification mechanisms to track China’s military buildup in future. Meanwhile, Washington needs to plan for a contingency in Indo-Pacific, in which India’s top priority is ensuring border peace with China, instead of maritime cooperation across the Indo-Pacific, particularly in the Indian Ocean.

Muhammad Faisal is a PhD candidate at the University of Technology in Sydney researching Pakistan’s foreign policy decision-making as it navigates intensifying great-power competition across South Asia and the Indian Ocean region. Faisal was a Research Fellow at the Institute of Strategic Studies Islamabad for nearly seven years, where he tracked Pakistan’s regional relationships, particularly with China. He has also been a visiting fellow at the Stimson Center in Washington, D.C., and Center for Non-Proliferation Studies in Monterey, California.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of the New Lines Institute.