Read the Essay Here

More than five years have passed since the atrocities committed against the Rohingyas in the Rakhine State of Myanmar in August 2017 forced nearly a million of them to take refuge in Bangladesh. With the prolongation of the Rohingya crisis, newer challenges are emerging for Bangladesh. The Rohingyas living in the camps in Bangladesh are willing to return to their homeland. The International Court of Justice’s verdict on July 22, 2022, rejecting all four Preliminary Objections of Myanmar, has paved the way to ensure accountability, an essential mechanism for finding a solution to the Rohingya crisis. At the same time, there have been public statements from government officials in Bangladesh, China, and Myanmar that repatriation will start soon. However, critics, both within the country and outside, point out that such repatriation should not compromise the principle of nonrefoulment. In this context, in the last few years, several pathways to the repatriation of the Rohingya have been envisaged and brought to the attention of policymakers and other national and international stakeholders. Eight potential pathways can easily be identified.

1 The Bilateral Approach

Bangladesh engaged with Myanmar bilaterally from the beginning of the crisis. One could list at least eight meetings when the Memorandum of Arrangement (MoA) on the Return of Displaced Persons from Rakhine State was signed, on November 23, 2017. The last bilateral meeting took place virtually on June 14, 2022. But nothing concrete has materialized so far, although there have been developments between the two countries, with China’s participation – to which I will return below. However, from the beginning, there were specific weaknesses in the bilateral approach. Three could be flagged. One is the signing of an “Arrangement” between Bangladesh and Myanmar, in place of an “Understanding” or “Agreement.” One cannot help but point out that in signing a “Memorandum,” the weakest type is an “Arrangement.” This is because neither “Understanding” nor “Arrangement” has any legally binding force; they only indicate the “willingness” of the parties. Only an “Agreement” is legally binding on the parties. Moreover, there have been few examples of signing an “Arrangement” between two countries globally.

The MoA signed in Nay Pyi Taw stipulated that the return “will commence at the earliest and shall be completed in a time-bound manner agreed [to] by both parties.i It is easy to see that not only did the Rohingya did not return, but also, no period of time was mentioned in the “Arrangement.” The parties only agreed to the “process of return.” Such, “process of return shall commence within two months of the signing of this Arrangement.”ii However, there is a vagueness in how this “process” is to be completed. The signed document only mentions that the “process” shall be “completed within a reasonable time from the date the first batch of returnees is received.” This flexibility allowed Myanmar to flout and delay the process and the period. Second, a Joint Working Group will be established “within three weeks of signing this arrangement.”iii This has occurred – but, so far, without progress on repatriating the Rohingyas residing in Bangladesh. Third, “a specific instrument on the physical arrangement for the repatriation of returnees will be drawn up upon agreement in a speedy manner following the conclusion of this Arrangement.”iv No such “agreement” has been reached in the last five years, or since the signing of the “Arrangement” in 2017, which only shows the limitation of the wording “speedy manner”!

In the bilateral meeting, however, one crucial issue seems to have been ignored. This relates to Myanmar committing “genocide” or “crimes against humanity.” On the contrary, the foreign minister of Bangladesh handed over three ambulances for their use in Rakhine State as a gift from Bangladesh to Myanmar on the day of the signing the MoA. A gesture of this kind does not show that Bangladesh was dealing with a “genocidal regime” or a regime that has committed violent atrocities against its residents, the evidence for which was abundant from the day the Rohingyas were driven out in August 2017. Moreover, the body language of the Bangladesh delegation remained subdued, although Bangladesh could have engaged with Myanmar on a high moral ground, particularly given the fact that the latter had committed mass atrocities against the Rohingyas.

What were the reasons for this? Three factors seem to have played out. The first was Foreign Minister Mahmud Ali’s earlier experience dealing with Myanmar on the Rohingya exodus. Mahmud Ali negotiated the Burmese Refugees Repatriation Agreement in 1992, when he was the country’s additional foreign secretary. This probably gave him the confidence that this time, too, he could pull it off and have the Rohingyas return to Arakan without delay, without realizing that this time the context was markedly different. Not only was there evidence that the Myanmar military had committed mass atrocities, even genocide, but also that Myanmar had entered the global world with key Asian countries – including China, India, and Japan – on its side, with the Western countries having withdrawn sanctions after Aung San Suu Kyi’s release and her assuming governmental power. Second, Bangladesh could have been advised by “friendly countries” to have the MoA signed, with Bangladesh believing that such countries would be able to impress upon or pressure Myanmar for a quick repatriation of the Rohingyas. And third, Bangladesh also wanted a quick solution as part of its civilizational quest of not having conflicts with its neighbors and focusing more on its robust developmental trajectory. This point may sound odd, but it should not be minimized, particularly considering the fact that Bangladesh never saw Myanmar as an “enemy.” Instead, Bangladesh, despite hosting over 1.1 million Rohingya refugees, a population larger than Bhutan’s, continues to have regular trading and other relations with Myanmar. However, whatever the merit of this approach, nothing productive has resulted from Bangladesh engaging with Myanmar bilaterally on the Rohingya issue.

2 The Multilateral Approach

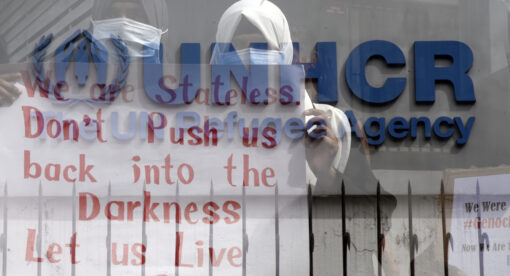

The involvement of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) on the Rohingya issue has been critical, with its role mentioned as early as November 2017 in the Memorandum of Arrangement: “UNHCR and other mandated U.N. agencies as well as interested international partners would be invited to take part, as appropriate, in various stages of return and resettlement, and to assist returnees in carrying on life and livelihood as members of Myanmar society.”v It took another six months, until May 2018, for Myanmar to sign a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) and UNHCR, which categorically stated that “after the necessary verification, those who have left Myanmar are to return voluntarily and safely to their households and original places of residence or a safe and secure place nearest to it of their choice.vi However, there has not been much headway in the repatriation of the Rohingya. On the contrary, the multilateral approach, particularly as undertaken by UNHCR and other mandated U.N. agencies, has focused more on Bangladesh than Myanmar. Flagging one area – education, for instance – would suffice to provide credence to the contention.

The U.N. agencies have impressed upon Bangladesh that it needs to provide education to the Rohingya refugees, but what kind of education is meant? According to the Office of the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees, “refugee children need to be included in the national education systems of their host countries.”vii This would suggest that the Rohingya refugees get an education in a “formal curriculum” and in the local language. Understandably, the Rohingyas must be able to communicate with the host community’s members. But given the context that the Rohingyas are not only “refugees” but are also “stateless,” not knowing Burmese and English would add to their plight, as it would further marginalize them from the majority Burman population and jeopardize their future when they return to Myanmar.

However, a balance could be struck on the issue of language. This could be done by pursuing a twofold policy. First, it would entail implementing 100% literacy – indeed, not only for the 73 percent illiterate Rohingya refugees but also for the 60.7% illiterate members of the host community in the Cox’s Bazar district.viii Second, it would mean rendering knowledge of English to Rohingya refugees and children of the host community. At the regional level, knowing English would help the members of both communities communicate and gain employment both within and beyond borders. The protection area, or safety net, needs to be broadened to include the Rohingya refugees and the vulnerable local population residing in the vicinity.

Employment opportunities of this precise kind should also be explored, in fact, of the type that would make the Rohingyas equally, if not more, helpful once they are repatriated to Myanmar. Becoming skilled in as many languages as possible would only add to the opportunities of the job seeker. Indeed, only at their peril could Bangladesh and the international community ignore the education of the refugees and the host community members. But then, when Bangladesh decided to relocate 100,000 Rohingya refugees out of the total 1.1 million to Bhasan Char Island in the Bay of Bengal, 60 kilometers from the mainland, mainly to provide skills development training for agricultural work,ix the international community, including nongovernmental humanitarian agencies, objected to the relocation on the ground that the island is not safe for habitation.

Only in May 2021, after over a year of procrastinating and when some 13,000 Rohingyas had already been moved to the island at Bangladesh’s expense, did the U.N. agencies agree to support the relocated Rohingyas. Still, only 30,000 Rohingyas have been relocated out of the proposed 100,000.x Funds for relocation were flagged repeatedly, more so because the funding for the Rohingyas has been gradually declining since the COVID-19 pandemic hit the economy of donor countries in 2020, followed by the ongoing Russia-Ukraine war since February 2022. One estimate shows that in 2019, Bangladesh and the U.N. agencies raised $636.7 million out of the $920.5 million required for the refugee program. But in 2022, the donors delivered only half the budget of $881 million.xi In the meantime, the entire gaze of the international humanitarian agencies, despite the May 2018 MoU cited above, shifted from Myanmar to Bangladesh, which must have made Myanmar even less interested in pursuing the repatriation of the Rohingyas and resettling them. Yet the multilateral approach, including the involvement of the U.N. and other agencies, remains critical for resolving the plight of the stateless Rohingyas.

3 The Tripartite Pathway

Bangladesh, Myanmar, and China agreed to form a “tripartite joint working mechanism” for Rohingya repatriation in New York on September 24, 2019. Subsequently, several trilateral meetings were held. The most recent meeting took place in Kunming in April 2023, amid news that a pilot project on repatriation would commence before the rainy season. But before assessing the pros and cons of the tripartite meeting in Kunming, it is worth pointing out China’s interests in resolving the Rohingya crisis. Three reasons could be flagged.

The first reason is Chinese investments and the quest for stability. China has been Bangladesh’s largest source of foreign direct investment since 2022. In fiscal year (FY) 2021-22, China invested approximately $940 million in Bangladesh.xii Moreover, China remains Bangladesh’s most influential trading partner. The bilateral trade between the two countries showed robust growth of 58% in FY 2022.xiii However, China’s investment in Myanmar has been more significant than Bangladesh’s. One estimate shows China invested over $25 billion from 1988 to June 2019.xiv Even since the military coup in February 2021, China’s investment in Myanmar has remained as steady as ever. Economic investments in both countries also compel China to seek stability, lest the investments become too risky and costly.

Second, China wants to offset Western influences in Myanmar. This has made China remain at Myanmar’s side, despite Myanmar’s serious human rights violations over the years – including in the postcoup period since February 2021, which saw more than 3,000 civilians killed, nearly 17,000 detained, and more than 1.5 million displaced.xv This has become all the more important since the United States’ declaration of the Burma Act 2023, which allows the Biden administration to interpret the act more liberally, mainly when providing military aid to ethnic armed organizations.xvi The act also gives the Biden administration the discretionary authority to make significant changes.xvii This has undoubtedly compelled China to put pressure on Myanmar for an early resolution of the Rohingya crisis, including initiating a process for their repatriation to the Arakan, lest the region become ripe for conflicts, with the United States getting involved near the Chinese border.

Third, any breakthrough in the tripartite pathway, particularly in making the Rohingyas return to their ancestral lands in the Arakan and making them legal residents of Myanmar, would boost Chinese status in the region and the world. Besides Rohingya refugees returning to Myanmar, the Chinese three-phase plan of November 2017 sought a long-term solution based on poverty alleviation.xviii

However, the tripartite approach has yet to make much headway. In 2018 and 2019, the trilateral initiative failed to repatriate a single Rohingya from Bangladesh. This time, the three countries met in Kunming in April 2023 and planned to initiate a pilot project to repatriate over 1,000 Rohingya refugees. The initiative saw a 20-member Rohingya delegation visiting Arakan on May 5, 2023, to see the two model villages erected for the pilot project.xix Although it is too early to say whether the pilot project will materialize before the onslaught of the rainy season, as envisaged, the complexity cannot be underestimated. One is the mixed reaction among the members of the Rohingya delegation after the visit.xx The extent to which the Rohingyas are eager to compromise on their four-point demands – seeking national identification and citizenship rights, return of their original land or properties, rights to livelihood and movement, and security assurance – remains a core issue.xxi

Moreover, the UNHCR, although aware of the visit, is not involved in the tripartite initiative, which could dampen the enthusiasm among the Rohingyas for the pilot project. But given the international isolation of Myanmar, coupled with the factor of civil unrest at home and various judicial processes being undertaken against Myanmar on the issue of genocide, it is not difficult to see that Myanmar would want to initiate the repatriation in order to make a difference in its dismal position, both at home and abroad. At the same time, Rohingya repatriation, even in a pilot form, would provide an electoral dividend to the ruling party in Bangladesh, with the national election scheduled in two or three months. Initiating a pilot project on the Rohingya repatriation in the remaining months of 2023, possibly discreetly, cannot be ruled out.

However, this project is currently on hold, for three reasons. First, there are disputes between Bangladesh and Myanmar on the list provided by Bangladesh and the identity of the Rohingyas. These disputes have arisen more from the Rohingyas’ demand to resettle their original land, which the Myanmar military is not eager to do. Moreover, the Myanmar military has transformed some Rohingya lands beyond recognition. Second, the MoU reached between Myanmar and the UNDP and UNHCR in May 2018 has lapsed and needs renewal, which has yet to be done. Bangladesh and the international agencies require firm guarantees from the Myanmar military that the repatriated Rohingyas would feel safe and can engage in livelihood-related activities without fear and discrimination, something to which the Myanmar military has yet to commit and provide in writing. Finally, since only a few months are left before the Myanmar military would like to go slowly and wait for the outcome.

4 Accountability

The issue of accountability has seen significant developments in the last five years. The two provisional rulings at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) were the most promising ones, particularly for pursuing the crime of genocide committed by the Myanmar military against the Rohingyas and providing legal recognition of the Rohingya identity. This was achieved unanimously with the consent of judges from Myanmar, China, India, Russia, and many more countries. Let me elaborate on this.

The ICJ hearing on the Rohingya genocide was held in The Hague on December 10-12, 2019. This is a unique case. An African country, The Gambia, brought charges against an Asian country, Myanmar, for committing genocide against the Rohingyas in the Arakan. This is something that no one expected. Indeed, if it surprised the world, it surprised Myanmar the most. In less than two months after the hearing on January 23, 2020, the ICJ granted the provisional measures requested by The Gambia.xxii Two things from the provisional measures stand out clearly.

First, the order of the ICJ was unanimous. This Myanmar had never expected. In all probability, Myanmar was looking for a split decision at the ICJ, which would have allowed it to rally at home that not all members had agreed to the provisional measures and, therefore, the order could be ignored. Fortunately for the Rohingyas and those supporting their cause, this did not happen. Second, the ICJ identified the group at the center of the case as “Rohingyas.” This statement by the ICJ is worth noting:

The Court’s references in this Order to the “Rohingya” should be understood as references to the group that self-identifies as the Rohingya group and that claims a longstanding connection to Rakhine State, which forms part of the Union of Myanmar.xxiii

Indeed, this was a significant victory for the Rohingyas, with implications far beyond the provisional measures. In many ways, it was a direct slap on the face of Myanmar for keeping a taboo on the word “Rohingya.” There is no denying the fact that the recognition of the “Rohingya identity” remains critical. If anything, it is the most significant stumbling block and, conversely, a way to resolve the crisis.

The disruptive policy of Myanmar, which has gradually disenfranchised and dehumanized the Rohingyas, comes from an “unspoken racial feeling” of the military and civilian elite of the country. This, unfortunately, found a “legal” expression in the 2008 National Constitution of Myanmar. As Thant Myint-U points out:

The Constitution … included an arcane formula tied to race. Any taing-yintha (or multinational races) “whose population constitutes at least 0.1% of the national populace” (around 50,000 people in 2010) was entitled to representation in local legislative assemblies and ministerial portfolios in local administrations. If a taing-yintha constituted more than half of two contiguous townships, it was entitled to an “autonomous zone.” So, in addition to ethnically-based states for the Shan, Kachin, and five others, there would now be “self-administered zones” for the Nagas, Danus, and a few smaller ethnic groups.

I’ve heard many Burmese warn that giving Muslims in northern Arakan taing-yintha status, as “Rohingya,” would lead automatically to their being entitled to a zone of their own. “A part of Burma would fall under Sharia law,” a university lecturer whispered. To consider the Muslims of northern Arakan as one of the “National Races” fused anxieties around both race and religion. The ethnonym “Rohingya” was particularly toxic for this reason, as it means literally “of Arakan” and therefore implied that those to whom it referred were indigenous. On the other hand, if they were called “Bengalis,” they could be seen … as immigrants and not natives deserving special protection and special rights (Myint-U, 2020:108-109).xxiv

Good sense prevailed during the hearing at the ICJ, where Suu Kyi and her team refrained from using the words “Bengalis” or “illegal migrants” for the Rohingyas. Given the proliferation of research on the Rohingyas in recent times, Myanmar is well aware that labeling the Rohingyas as “Bengalis” or “illegal migrants” would take them nowhere. Instead, this would make them closer to being accused of committing genocide against the Rohingyas. Myanmar also knows that the International Criminal Court has opened an investigation into crimes committed against the Rohingyas in Arakan. Also, there is a lawsuit pending in the Argentinian Supreme Court on the issue of the Myanmar military committing genocide against the Rohingya population. Furthermore, now that the United States has officially declared that the Myanmar military has committed genocide against the Rohingya, the issue of accountability will get an additional boost and pressure the Myanmar military to resolve the issue.

5 Reimposing Sanctions

Economic pressure in the form of sanctions on Myanmar is required. Although sanctions often economically harm the disempowered more than the empowered, the West has utilized sanctions, not always from the standpoint of economic merit but also on moral grounds, which certainly brings pressure on the sanctioned regime to reform and rectify within. The United States withdrew sanctions from Myanmar in 2016, followed by other countries. This is where the Myanmar military cleverly used Aung San Suu Kyi. Her acceptance by the military created space for sanctions to be withdrawn and allowed Myanmar to begin globalization. Many would argue that the Myanmar military created a semblance of democracy and allowed Suu Kyi to come to power precisely because sanctions made it difficult for the military to govern the population and cleverly assessed that the West would fall for the bait and withdraw the sanctions if space were provided to Suu Kyi, even if it was on the military’s terms. However, now, with Suu Kyi’s internment, the time has come to reimpose sanctions, which will make a difference not only to the lives of the Rohingyas but also to the Myanmar people who have been suffering since February of last year.

Sanction politics has come back since the start of Russia’s war with Ukraine. However, it must be quickly pointed out that the international community, particularly the Western countries, did not shy away from imposing sanctions on Iran, North Korea, and even China on various items. There is no reason, therefore, not to reimpose sanctions on Myanmar because of its perceived noneffectiveness. Anything less at this stage will only empower the Myanmar military. In December 2016, U.S. President Barack Obama lifted sanctions against Myanmar, saying “it had made strides in improving human rights.”xxv But a year later, under President Donald Trump, new sanctions were imposed on Myanmar military commanders in 2018 and 2019, as evidence of atrocities by the military came to light.xxvi

Western countries have thus far imposed sanctions only on military personnel and companies in Myanmar. The United States has placed visa and financial sanctions on 9 Myanmar military officers, including Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, and on two military units for their involvement in attacks on Rohingya and Burmese civilians.xxvii The European Union also sanctioned 22 Myanmar military officials and some gas companies,xxviii which has hardly impacted the Myanmar military. Sanctions on a larger scale to put pressure on the military are still absent. Moreover, the current sanctions were imposed in response to Myanmar’s recent military coup and are unrelated to the Rohingya issue.

A beginning on reimposing sanctions could be made by exposing and shaming the companies that have invested in Myanmar, by telling them that since they are profiting from a country that is killing its people and has forcibly displaced 1.1 million of its population and is now under investigation for committing genocide and crimes against humanity, these companies will also be held responsible for their “complicity in crime” if they continue to profit from their investments. It is worth pointing out that foreign direct investment (FDI) flows into Myanmar increased by $259.6 million in the quarter ending in September 2022, compared with an increase of $392.5 million in the previous quarter.xxix Moreover, Myanmar approved $1.45 billion in FDI during the first seven months of 2022-23, mainly from Singapore, a conduit for foreign money into Myanmar and China.xxx In this context, investigative information would be required because the Myanmar military has stopped disclosing the projects it has approved since the coup.

But the sad aspect here is that Myanmar is still eligible for trade benefits from the United States under the General System of Preferences. Even the Burma Act makes an exception for U.S. imports from Myanmar.xxxi This sends the wrong signals to Myanmar and U.S. allies that maintain trade preference programs with Myanmar. At the same time, international financial institutions provide significant development funding to Myanmar. For instance, the World Bank announced $460 million in credits to upgrade electricity power generation and improve health services.xxxii There ought to be sanctions on such projects until the discriminatory laws, policies, and practices are addressed. The international community, particularly the Western countries that campaign for a rule-based international order, must use its collective influence to ensure that sanctions are reimposed, so that the Myanmar military will feel pressure to resolve the Rohingya crisis.

6 A Policy of Decoupling

“Decoupling” refers to a policy, widely practiced by various countries, that means to separate a particular activity from others. The former policy is pursued while contradicting the latter policy, in order to attain critical objectives. This is mainly because countries have varied interests and priorities, which are not always all equally important but are carried out to meet urgent national goals. This creates space for separating one policy from the other without jeopardizing the country’s relationships and core national interests. Some countries, for instance, have strategic and economic interests in Myanmar, and thus policy changes cannot be brought about instantly. This is understandable, but such countries also have the power to impress upon Myanmar the need to change its policy in a different area by taking action related to that area. In situations like this, what is required from such countries is to decouple the Rohingya issue from their strategic and financial interests.

This is where Japan made a difference when it cosponsored a resolution in the United Nations in November 2021 favoring the Rohingya community.xxxiii Although this was done in the context of changes in Myanmar in February 2021, which saw the removal of Suu Kyi and the military takeover of the government, with the U.N. Myanmar seat held by the forces favorable to the former, it is still a good sign that a longtime strategic partner of Myanmar decided to put pressure on the latter by decoupling the Rohingya issue from its strategic interests. Japan formerly used to abstain from such resolutions, but by cosponsoring the resolution, Japan for the first time decoupled the Rohingya issue from its strategic interests in Myanmar. And since Japan cosponsored the resolution, it is bound to put pressure on Myanmar.

Even by recognizing the “Rohingya identity,” pressure is being put on Myanmar to change its decision of not recognizing the Rohingya community as one of the ethnic groups of Myanmar. Myanmar so far recognizes 135 ethnic groups clustered in eight “national races.”xxxiv It may be pointed out that several countries, including Myanmar, refer to the Rohingyas as “Arakanese Muslims” without realizing that there are also Rohingya Hindus,xxxv and even Rohingya Christians.xxxvi More importantly, one should use the word “Rohingya” mainly because the ICJ, to which all U.N. members are legally bound, has recognized the community as Rohingya. Therefore, there is no reason why “Rohingya” should not be used while discussing the latter’s plight vis-à-vis Myanmar. That itself would contribute to decoupling and putting pressure on Myanmar. Similarly, inviting a Rohingya delegation to India or Japan, for instance, would decouple the Rohingya issue from these countries’ core strategic or economic interests and make Myanmar realize that the Rohingya issue will not go away. Instead, the more quickly it is resolved, the more stable and comprehensive these countries’ relationships will be.

But unfortunately, one also sees other kinds of decoupling, which only go on to empower the Myanmar military, to the detriment of the Rohingyas’ lives and of the dissenting forces supportive of the National Unity Government in exile. This relates mainly to the sale and manufacturing of weapons. The following report is noteworthy:

Companies in the United States, Europe and Asia have been helping Myanmar’s military manufacture weapons used in human rights abuses, according to three former United Nations experts. Companies from 13 countries – including France, Germany, China, India, Russia, Singapore and the United States – have been providing supplies that are “critical” to the production of weapons in Myanmar. … It found that high precision machines manufactured by companies based in Austria, Germany, Japan, Taiwan and the U.S. are currently being used by the Myanmar military at its weapons factories. … Software to operate these machines is being provided by companies based in France, Israel and Germany. … Singapore, meanwhile, functions as a strategic transit point for potentially significant volumes of items, including certain raw materials, that feed the Myanmar military’s weapons production, and Taiwan is believed to serve as an important route for the military’s purchase of the high precision machines. … The military also regularly sends these machines from KaPaSa factories to Taiwan, where they are serviced by technicians associated with the European manufacturers of the machines, after which they are shipped back to Myanmar.xxxvii

The countries mentioned in the report often emphasize a rule-based international order and the need for democratic principles and human rights to thrive in Myanmar. But at the same time, they have no qualms in decoupling such principles, selling weapons to Myanmar, and profiting from this. The time has come to expose and shame such deals while impressing on their practitioners the need to decouple their arms sales and pressure Myanmar to resolve the Rohingya crisis.

7 Economic Incentives

The idea of offering economic incentives may sound odd, particularly with the backdrop of Myanmar committing genocide against the Rohingyas. But let us take a dispassionate or “realist” look at this approach. It is already known that the Myanmar military is either directly or indirectly involved in the drug trade, particularly for Yaba, a synthetic drug composed of a methamphetamine substance. Historically, Myanmar has always been a significant producer of opium, which has contributed to the country’s gross domestic product. UNODC recently provided data on the opium cultivation in Myanmar, which has seen a declining trend.xxxviii However, the decline in opium cultivation has resulted in a situation where drug lords, albeit with the connivance of the Myanmar military, have shifted their illicit narcotics production from natural to synthetic drugs.

The bulk of the production takes place in Myanmar’s Shan state. Looking at the output, one can easily see its enormity. One recent report revealed that the authorities in Laos, Thailand, and Myanmar seized 90 million methamphetamine tablets and 4.4 tons of crystal methamphetamine in January 2022 alone,xxxix which gives us a sense of the size of the trade. More than 70% of seizures of Yaba occurred in the Cox’s Bazar district,xl mainly because of its geographical location, as it shares a critical border with Myanmar. Not surprisingly, there are indications that the Myanmar military profits from Yaba production and its distribution worldwide, including in Bangladesh.

The seizure of Yaba went up sharply after the Rohingya exodus in 2017 and peaked in 2020. The Rohingyas, however, are not consumers of Yaba; one hardly finds a severe addict among the Rohingyas. However, the Rohingyas became involved in the narcotics trade because of the opportunity to earn quick money, which caused a steep rise in drug-related incidents in Bangladesh, particularly in the Cox’s Bazar area.xli But since 2021, mainly due to the efforts of the Bangladesh Border Guards and other security agencies, there has been a steady decline in the seizure of Yaba.xlii This gives the impression that the flow of Yaba is on the decline. But this is very deceptive, because there has been a steep rise in the seizure of crystal meth ice, which is nothing but concentrated Yaba and is more profitable when drug dealers successfully transport it. It is worth pointing out that Myanmar has long been a leading producer and trafficker of illicit drugs, with drug exports generating $1-2 billion annually.xliii The trafficking and selling of illegally mined jade and gemstones also bring benefits of up to $31 billion annually.xliv During the 1990s, the Myanmar military increased its cooperation with several insurgent groups in the region. In exchange for a cease-fire, the government placed the insurgent groups’ territory beyond the reach of Burmese law. This agreement allowed insurgents and the military junta to create partnerships to increase trade in illegal goods, including drugs, gems, and timber.

The Myanmar military has no qualms about getting involved in the lucrative illicit drug trade. From wildlife and human trafficking to smuggling illegal drugs, jade, and gemstones, Myanmar’s informal economy is expansive and is often facilitated by its military. In fact, over the years, the Myanmar military has transformed itself into a “military-business complex” (MBC), which thrives on the illicit narco-trade, instability, and conflicts. Not surprisingly, as an MBC, the Myanmar military would need economic incentives that are more significant than the illegal drug trade to see benefits from the repatriation of the Rohingyas.

This could come in two ways. The first one is by initiating a mini–Marshall Plan with international support. Many have forgotten that the Marshall Plan made a difference in post–World War II Europe.xlv Europe’s number of refugees after World War II was in the millions. But the Marshall Plan helped reorganize and develop Europe in many ways. The time has come to think of a mini–Marshall Plan in the Arakan, which would be attractive to the Myanmar military, and thus would enable it to shun the illicit drug trade and repatriate the Rohingya refugees residing in Bangladesh and elsewhere.

The second way is an offshoot of the first one. A concerted effort is required to establish special economic zones, employing many marginalized people in the bordering states, including Rohingyas. Public-private partnerships between Bangladesh and Myanmar in the Arakan could also benefit the Rohingyas. Such economic engagements are bound to make the Rohingyas’ repatriation more saleable to Myanmar. The international community must work together to create space for legal business to flourish and make the MBC more formal and legal. A mini–Marshall Plan tied to the Rohingyas in the Arakan is otherwise required to interest Myanmar in resolving the Rohingya crisis.

8 Militancy

There is still a mystery regarding the events that exacerbated the Rohingyas’ exodus to Bangladesh in August 2017. Four dates in 2017 are critical. On August 23, the Advisory Commission on the Rakhine State (i.e., the Kofi Annan Commission) submitted its final report to the Myanmar national authorities. On August 24, the media, both at home and abroad, published the report in detail. On August 25, the so-called Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) attacked the Myanmar military forces. The very next day, August 26, the Myanmar military resorted to what came to be referred to as “a textbook case of ethnic cleansing,”xlvi which in the next three months saw more than 750,000 Rohingyas, mostly women and children, flee Myanmar to take refuge in Bangladesh. The mystery lies in the militancy of ARSA: why would it resort to violence and attack the Myanmar military forces when the Annan Commission’s report remains favorable to the cause of the Rohingyas, including the need to provide them with citizenship in Myanmar? As the report stated:

The Commission … notes the need to revisit the [1982 citizenship] law itself and calls on the government to set in motion a process to review the law. Such a review should consider – amongst other issues – aligning the law with international standards, re-examining the current linkage between citizenship and ethnicity, and considering provisions to allow for the possibility of acquiring citizenship by naturalisation, particularly for those who are stateless. The Commission calls for the rights of non-citizens who live in Myanmar to be regulated, and for the clarification of residency rights.xlvii

Does this mean that the Myanmar military created a pretext in the name of ARSA? Or could it be that the Myanmar military, as part of its counterinsurgency strategy, floated an “armed group” called ARSA? Whatever the case, it confirms the intricate relationship between militancy and the Rohingya crisis – one feeds into the other, which is even more the case for the stateless Rohingya refugees. Historically, youth have been the first to rebel against oppressive conditions. Most Rohingyas residing in Bangladesh refugee camps are between 15 and 24 years of age, and they constitute approximately 22.41% (199,431 youth) of the Rohingya population in Cox’s Bazar (899,704).xlviii Naturally, the nonresolution of the Rohingya issue would make youth restless; some of them would not shy away from joining the militant forces and taking up arms against the Myanmar military in order to forcibly impress upon them the need to recognize the Rohingya identity and enable the displaced Rohingyas to return to their native land in the Arakan.

Moreover, suppose the Myanmar military does not settle the Rohingya repatriation issue, even under international pressure? In that case, it will create space for armed militant groups among the Rohingyas and the disaffected youth of Myanmar to rise up against the Myanmar military. Insurgent groups favorable to the Rohingyas’ cause can create alliances with other insurgent groups in the region. The Myanmar government’s inaction on the Rohingya repatriation issue could give it more public support in the future. Fringe militant groups have also emerged among the Rohingyas on both sides of the border. They can become more organized in the future and join the insurgency in Myanmar to ensure Rohingya repatriation.

There is an additional, more sinister, problem. The Bangladeshis who wholeheartedly welcomed the Rohingyas in the early days of the exodus could aid them with arms and ammunitions, given their historical record of empathizing with victims, apart from their constitutional obligation to support “oppressed peoples throughout the world” (Article 25, para. C, of the Constitution of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh). There have been historical instances of militancy paving the way for refugee repatriation. The most remarkable example is the 1971 Liberation War of Bangladesh, when 10 million Bengali refugees went to India to flee the genocide committed by the Pakistan military. The armed struggle of the Mukti Bahini of Bangladesh, which was supported by India and other external actors, set the path for the country’s independence and the refugees’ subsequent repatriation. The militant approach might be the least desirable but probable one, if the international community fails to reason with the Myanmar military regarding restrictions on repatriating the Rohingyas. However, the militant pathway is bound to destabilize the region, which would only see international and regional actors getting involved in either supporting or quelling the militancy, from the standpoint of their respective national and strategic interests. And therein lies the fear!

In Lieu of a Conclusion

All these eight potential pathways are significant. Collectively, they are like an octopus, and one should be cognizant of all the paths to see how one can resolve the Rohingya crisis. If someone thinks the Rohingya issue will disappear because of other pressing global problems, they are only looking at one or two pathways. Each pathway has its momentum, and once it unrolls, despite limitations and difficulties, there is no way it can be stopped unless and until the crisis, which has given birth to the pathways, is resolved. No ideas and practices that are grounded in reality can be erased. They can sometimes become challenging, but when found relevant to people for determining the course of the crisis, they return and make their presence all the more urgent. Interventions on the part of Bangladesh and the international community, again at three interrelated levels, can make the eight pathways effective.

At the first, national level, Bangladesh’s policymakers need to spend more time resolving the Rohingya crisis. The Government of Bangladesh (GoB) could fall back on one of its success stories, the resolution of maritime boundaries with India and Myanmar, where the GoB had a dedicated expert with the rank of additional secretary and later secretary working full time on the issue. The additional secretary worked in consultation with the foreign minister and foreign secretary, but having a dedicated expert made a difference to this case. Likewise, it is high time to appoint a dedicated expert on the Rohingya issue, with the rank of additional secretary or secretary, who will have a dedicated team with members from all relevant sectors to work on the various options and provide workable suggestions to the government. At the same time, the GoB should activate its foreign missions and members of civil society, including the media, to highlight the plight of the Rohingya refugees nationally, regionally, and internationally. Second, the stakeholders should give more effort to regional initiatives, including engaging countries that are friendly to Myanmar. Tripartite meetings on the Rohingya crisis involving Myanmar, Bangladesh, and a supportive third country, both at Track 1 and 2 levels, should be initiated to put pressure on Myanmar and let the other countries know of the crisis’s urgency. Third and finally, a more significant effort ought to be started at the international level, including supporting the Rohingya diaspora community in forming a Rohingya civil entity, which would then take the responsibility to flag its cause internationally, including at the United Nations, European Union, and other international bodies. The proposed Rohingya civil entity also needs to work on the kind of economic, educational, and even health policies it plans to pursue once the Rohingyas return to their motherland, with the full dignity of the person.

Looking back at the eight pathways, one can easily see that some are more promising. Still, it is too early to say which one or two will have a lasting impact on the outcome of the Rohingya crisis. At this stage, impatience will not help. The Rohingya crisis is a human issue; therefore, one should have faith in humans if one is looking for a resolution to the plight of the Rohingyas in Myanmar.

Endnotes

1 Taw, N.P. (2017, November 23). Arrangement on Return of Displaced Persons from Rakhine State Between the Government of the People’s Republic of

Bangladesh and the Government of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar.

2 Taw, N.P. (2017, November 23). Arrangement on Return of Displaced Persons from Rakhine State Between the Government of the People’s Republic of

Bangladesh and the Government of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar.

3 Taw, N.P. (2017, November 23). Arrangement on Return of Displaced Persons from Rakhine State Between the Government of the People’s Republic of

Bangladesh and the Government of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar.

4 Taw, N.P. (2017, November 23). Arrangement on Return of Displaced Persons from Rakhine State Between the Government of the People’s Republic of

Bangladesh and the Government of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar.

5 Taw, N.P. (2017, November 23). Arrangement on Return of Displaced Persons from Rakhine State Between the Government of the People’s Republic of

Bangladesh and the Government of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar.

6 Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population of the Government of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar (GoM), United Nations Development

Programme, Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. (2018, May 30). Memorandum of Understanding Between the Ministry

of Labour, Immigration and Population of the Government of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar (GoM) and the United Nations Development

Programme and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

7 United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). (2017). Turn the Tide: Refugee Education in Crisis. UNHCR.

8 The literacy rate of the Cox’s Bazar district stood at 39.3% in 2011. See Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, Government of Bangladesh. (2013). District

Statistics 2011: Cox’s Bazar.

9 UNB. (2023, March 2). Dhaka wants foreign funds to relocate 70,000 Rohingyas to Bhasan Char. Dhaka Tribune. https://www.dhakatribune.com/

bangladesh/305975/dhaka-wants-foreign-funds-to-relocate-70-000.

10 UNB. (2023, March 2). Dhaka wants foreign funds to relocate 70,000 Rohingyas to Bhasan Char. Dhaka Tribune. https://www.dhakatribune.com/

bangladesh/305975/dhaka-wants-foreign-funds-to-relocate-70-000.

11 Korobi, S.A. (2023, March 19). Declining Funds, food for Rohingyas. New Age, https://www.newagebd.net/article/197176/declining-funds-food-forrohingyas#:~:text=The%20World%20Food%20Programme%20reports,from%20acute%20malnutrition%20and%20anaemia.

12 The Financial Express. (2022, December 18). China now largest FDI source in BD. https://fairbd.net/chinese-investment-in-bangladesh-explained/#.

13 The Financial Express. (2022, December 18). China now largest FDI source in BD. https://fairbd.net/chinese-investment-in-bangladesh-explained/#.

14 Oinam, A. (2023, April 8). China’s Investments in the Post-Coup Myanmar: An Assessment. CLAWS – Centre for Land Warfare Studies, New Delhi.

15 Blinken, A. J. (2023, January 31). Marking Two Years Since the Military Coup in Burma. U.S. Department of State. https://www.state.gov/marking-twoyears-since-the-military-coup-in-burma/.

16 Martin, M. (2023, February 6). What the BURMA Act Does and Doesn’t Mean for U.S. Policy in Myanmar. CSIS. https://www.csis.org/analysis/whatburma-act-does-and-doesnt-mean-us-policy-myanmar.

17 Martin, M. (2023, February 6). What the BURMA Act Does and Doesn’t Mean for U.S. Policy in Myanmar. CSIS. https://www.csis.org/analysis/whatburma-act-does-and-doesnt-mean-us-policy-myanmar.

18 Reuters, Naypyitaw. (2017, November 20). China draws 3-stage path to resolve Rohingya crisis. The Daily Star. https://www.thedailystar.net/rohingyacrisis/china-draws-3-stage-path-ceasefire-myanmar-rakhine-bangladesh-asem-wang-yi-naypyitaw-1493917.

19 Al Jazeera. (2023, May 5). Rohingya delegation visits Myanmar amid latest repatriation plans. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/5/5/

rohingya-delegation-visits-myanmar-amid-latest-repatriation-plans#:~:text=A%20Rohingya%20refugee%20delegation%20has,persecuted%20

minority%20to%20their%20homeland.

20 NewAge Bangladesh. (2023, May 25). Repatriation Scheme: Myanmar team visits Rohingya again. NewAge Bangladesh. https://www.newagebd.net/

article/202533/myanmar-team-visits-rohingyas-again.

21 NewAge Bangladesh. (2023, May 25). Repatriation Scheme: Myanmar team visits Rohingya again. NewAge Bangladesh. https://www.newagebd.net/

article/202533/myanmar-team-visits-rohingyas-again.

22 International Court of Justice. (2020). Reports of Judgments, Advisory Opinions and Orders Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment

of the Crime of Genocide (The Gambia v. Myanmar) Request for the Indication of Provisional Measures, Order of 23 January 2020.

23 International Court of Justice. (2020). Reports of Judgments, Advisory Opinions and Orders Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment

of the Crime of Genocide (The Gambia v. Myanmar) Request for the Indication of Provisional Measures, Order of 23 January 2020.

24 Myint-U, T. (2020). The Hidden History of Burma: Race, Capitalism, and the Crisis of Democracy in the 21st Century. W.W. Norton.

25 Albert, E., & Maizland, L. (2020, January 23). The Rohingya Crisis. Council on Foreign Relations.

26 Albert, E., & Maizland, L. (2020, January 23). The Rohingya Crisis. Council on Foreign Relations.

27 U.S. Department of State. (2023, March 24). Burma Sanctions; BBC News. (2021, February 11). Myanmar coup: U.S. announces sanctions on leaders. BBC

News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-56015749,

28 AP News. (2022, February 21), EU sanctions 22 Myanmar officials, gas company, over abuses. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/business-europeelections-myanmar-aung-san-suu-kyi-4613d6b2545ea9411dddfa3b58f8bf49.

29 CEIC Data. (1976-2022). Myanmar Foreign Direct Investment: 1976-2022. https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/myanmar/foreign-direct-investment

30 Chau, T. & Oo, D. (2023, February 2). ‘Riding a Rollercoaster’ in Myanmar’s post-coup economy. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/2/2/

riding-a-rollercoaster-in-myanmars-post-coup-economy#:~:text=Deepening%20conflict%2C%20sudden%20changes%20to,in%20the%20country%20

increasingly%20challenging.

31 Martin, M. (2023, February 6). What the BURMA Act Does and Doesn’t Mean for U.S. Policy in Myanmar. CSIS. https://www.csis.org/analysis/whatburma-act-does-and-doesnt-mean-us-policy-myanmar.

32 The Irrawaddy. (2020, June 1). World Bank Approves $460 Million Funding for Power Generation, Health Services in Myanmar. The Irrawaddy. https://

www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/world-bank-approves-460-million-funding-power-generation-health-services-myanmar.html.

33 UNB, Dhaka. (2021, November 18). UN adopts resolution on Rohingyas’ human rights in Myanmar. Daily Star. https://www.thedailystar.net/news/asia/

south-asia/news/un-adopts-resolution-human-rights-rohingya-muslims-myanmar-2232986.

34 Archives. Myanmar People and Races. https://web.archive.org/web/20100609072939/http://myanmartravelinformation.com/mti-myanmar-people/

index.htm

35 Mithun, M. B., & Arefin, A. (2020, November 26). Minorities among Minorities: The Case of Hindu Rohingya Refugees in Bangladesh. International

Journal on Minority and Group Rights, 28(1), 187-200. https://doi.org/10.1163/15718115-bja10020.

36 International Christian Concern. (2021, April 2). Myanmar’s Persecuted Rohingya Christians – Minority of Minorities. Persecution.org. https://www.

persecution.org/2021/04/02/myanmars-persecuted-rohingya-christians-minority-minorities/.

37 Al Jazeera. (2023, January 16). Firms in Europe, U.S. helping Myanmar manufacture arms, report says. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.

com/news/2023/1/16/firms-in-europe-us-helping-myanmar-manufacture-arms-report#:~:text=Companies%20from%2013%20countries%20

%E2%80%93%20including,a%20report%20released%20on%20Monday.

38 UNODC Regional Office for Southeast Asia and the Pacific. (2021, February 11). UNODC report: opium production drops again in Myanmar as the

synthetic drug market expands,. UNODC Regional Office for Southeast Asia and the Pacific, United Nations. https://www.unodc.org/roseap/en/2021/02/

myanmar-opium-survey-report-launch/story.html.

39 Strangio, S. (2022, February 2). Illicit Drug Production Has Surged Since Myanmar’s Coup. The Diplomat. https://thediplomat.com/2022/02/illicit-drugproduction-has-surged-since-myanmars-coup/..

40 Department of Narcotics Control, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh. (2020). Annual Drug Report Bangladesh 2020.

41 Ahmed, I., & Biswas, N. R. (2022). Rohingyas in Myanmar and Bangladesh: The Violence-Protection Dialectic and the Narratives of Certain Unsafety /

Uncertain Safety. Centre for Genocide Studies, University of Dhaka and Institute for Risk and Disaster Reduction, University College London.

42 Ahmed, I. (2022, September). Myanmar, Narco-terrorism, Rohingya, and the World. Diplomats World.

43 Marrero, L. (2018, June 15). Feeding the Beast: The Role of Myanmar’s Illicit Economies in Continued State Instability. International Affairs Review.

44 Levin, D. (2015, October 22). Myanmar’s Jade Trade Is a $31 Billion ‘Heist,’ Report says. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/23/world/

asia/myanmars-jade-trade-is-a-dollar31-billion-heist-report-says.html.

45 Agnew, J., & Entrikin, J. N. (Eds.). (2004). The Marshall Plan Today Model and Metaphor (1st ed.). Routledge.

46 UN News. (2017, September 11). UN human rights chief points to ‘textbook example of ethnic cleansing’ in Myanmar. United Nations. https://news.un.org/

en/story/2017/09/564622-un-human-rights-chief-points-textbook-example-ethnic-cleansing-myanmar#:~:text=%E2%80%9CThe%20situation%20

seems%20a%20textbook,access%20to%20human%20rights%20investigators.

47 Advisory Commission on Rakhine State. (2017, August 23). Overview of key points and recommendations. Towards a Peaceful, Fair and Prosperous

Future for the People of Rakhine: Final Report of the Advisory Commission on Rakhine State.

48 UNFPA. (2021, August 19). Transformative education for adolescent youth in the Rohingya camps, one micro-garden at a time. Reliefweb. https://reliefweb.

int/report/bangladesh/transformative-education-adolescent-youth-rohingya-camps-one-micro-garden-time#:~:text=In%202021%2C%203%2C600%20

adolescent%20youth,activity%20should%20not%20be%20underestimated.

This essay originally appeared in the anthology “The Accountability, Politics, and Humanitarian Toll of the Rohingya Genocide” To download the full anthology, click here.

Dr. Imtiaz Ahmed is a professor of International Relations at the University of Dhaka. He is also a visiting Pprofessor at Taylor’s University, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. He has authored, co-authored, and edited 55 books and 20 monographs and published more than 125 research papers and scholarly articles in leading journals and edited volumes. Ahmed heads several national and international projects on mass violence, violent extremism, and the Rohingya crisis. His recent publications are the following books: “Rohingyas in Myanmar and Bangladesh: The Violence-Protection Dialectic and the Narratives of Certain Unsafety/Uncertain Safety,” co-authored with Niloy Ranjan Biswas (Dhaka: 2022); “Imagining Post-Covid Education Futures,” edited (Dhaka: 2023); and “Celebrating 100 Years of the University of Dhaka: Reflections from Alumni – National and International, in 7 Volumes,” edited (Dhaka: 2023).