Listen to article

Two months after Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan declared his intention to launch a new offensive in northern Syria, the country’s frontlines remain static. Despite Erdoğan’s renewed efforts in late July to secure a blessing from Iran and Russia for the operation, outside powers remain united in their opposition to any changes to Syria’s front lines. Ankara’s original plan – a major offensive that would have placed all Syrian territory within 30 kilometers of the Turkish border under the control of Turkey or its proxies – has now been shelved in favor of an intensified campaign of drone strikes and artillery shelling against both military and civilian targets. With the Kremlin and the White House concentrating their attention on Ukraine, it is possible that Erdoğan will identify an opening to launch a new offensive regardless of their opposition, and these attacks would be a prelude, rather than an alternative, to a major military operation.

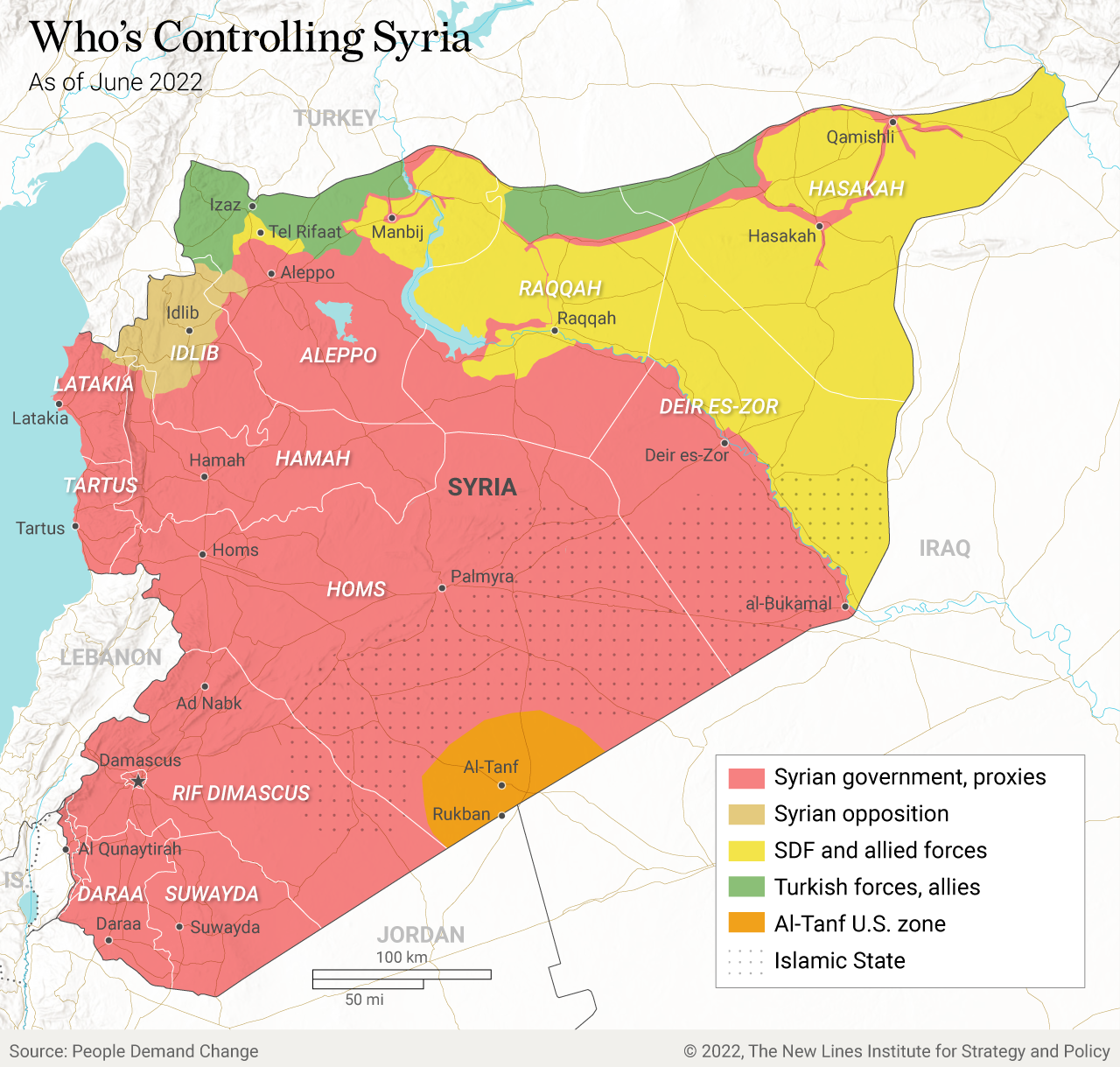

But with or without a new offensive, Turkish pressure has resulted in more subtle changes in the balance of power in the areas under the SDF’s control. With the United States unwilling to provide direct military support against Turkey, the SDF’s leadership has turned to other partners to buttress its positions along the front lines. The Assad regime and its allies have quietly expanded their military presence east of the Euphrates in the past two months, putting the SDF into increasingly close military cooperation with not only Damascus but also its Russian and Iranian allies.

The SDF’s increased cooperation with the regime and its allies to defend its territory has potentially seismic implications for northeast Syria, given Damascus’ longstanding goal of forcing U.S. and Coalition troops out of Syria and bringing the region back under the complete control of the central government. But despite new cooperation in the military sphere, the regime and the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES), the civilian body administering SDF-controlled territory, remain at odds over a political deal that would bring the region back under Damascus’ power.

Turkish Strikes in SDF Territory

The most notable of Turkey’s drone and artillery strikes was the July 22 attack that killed three prominent members of the SDF, including deputy commander Salwa Yusuf. That attack elicited a rare statement by the United States, expressing “condolences” for her death but refraining from naming a perpetrator or criticizing the attack itself. This attack was not unique. A Turkish drone strike on July 21 killed two SDF fighters near Kobani, a strike on July 28 killed four members of the AANES’ Internal Security Forces, and a drone attack on Aug. 4 killed a member of the Tel Tamer Military Council, an armed group under the SDF’s umbrella. Between July 20 and Aug. 2, the Syrian Democratic Council (SDC), the political wing of the SDF and the AANES’ highest civilian body, reported that strikes by Turkey and its proxies killed nine SDF fighters, four members of the Internal Security Forces, and 13 civilians.

Although this campaign’s explicit goal is to degrade the capabilities of the SDF, which the United States relies on to sustain the Coalition’s fight against ISIS in northeast Syria, the U.S. government’s response has been muted. High-level officials have been emphatic about their opposition to a new Turkish offensive, but have generally refrained from commenting on Turkish drone strikes against targets within SDF-held territory. Some analysts believe the U.S. may even be quietly supportive of these strikes, viewing them as an alternative to invasion and a substitute that may placate Turkey. Aside from U.S. Central Command’s statement on the death of Yusuf, and one other press release on a drone strike which killed four civilians on August 18th, Turkey’s recent intensification of attacks against the SDF have not been met with any public-facing comments by U.S. officials. None of the attacks, including the strike against Yusuf, resulted in any public criticism or acknowledgement of Turkey’s role in the attacks (a State Department spokesperson evaded a direct question on these attacks in late July.)

The SDF Looks for New Allies

Washington’s muted response to these attacks has prompted the SDF to seek other partners to buttress itself against Turkish pressure. Mazloum Abdi, the commander in chief of the group, first said in June that the SDF would strengthen military coordination with the Assad regime to thwart Turkish goals in the region. The group has now acted on that statement, allowing the regime to move at least 500 troops into northeast Syria, according to the Syrian Democratic Council. Since June, the Assad regime has sent troops to reinforce Manbij, Kobani, and Tel Rifaat, all of which are nominally under the control of the SDF or one of its constituent armed groups. The SDC described these moves as largely symbolic: They placate Turkey by allowing the SDF to pull its own forces back from certain checkpoints without ceding territory to Turkey or the regime. Nonetheless, Turkey carried out airstrikes against regime-held positions near Kobani on Aug. 16, reportedly killing multiple members of the Syrian military. The strikes were in retaliation for previous, SDF-claimed attacks against Turkish forces in northeast Syria, a clear sign that Turkey is not distinguishing between Assad-aligned and SDF-aligned troops when they are operating along the same front line.

The regime’s own troops, moreover, aren’t the only ones who have expanded their presence in north and east Syria. In the past two months, Russia has also been reportedly expanding its presence at the Qamishli airport, in the heart of the SDF’s territory, adding air defense systems, fighter jets, and attack helicopters to its base there. While this is not the first time Russia has been reported to deploy Pantsir S-1 air defenses or Su-35 fighter jets to the base, the deployments in the past month involved photo shoots and patrol videos seemingly designed to raise their profile and signal Russia’s commitment to a robust military presence in the area.

Although the SDF has not publicly welcomed these moves, they do coincide with Mazloum Abdi’s request for outside air defense systems, and the forces likely serve as an added deterrent against a renewed Turkish invasion.

Barriers to an AANES-Regime Deal

Despite their recent cooperation, the potential for a voluntary political settlement between the AANES and Assad regime remains remote. Damascus continues to insist on a return to the pre-war political structure, with nearly all power consolidated in the hands of the central government, but the AANES is only willing to accept a deal that makes accommodations for a federalized governance structure, with the areas under its control being granted autonomy. What that would ultimately look like in practice is unclear, but the Assad regime is notoriously averse to delegating authority outside of its inner circle. No progress toward a deal has been made despite long-running negotiations between the two sides.

According to the SDC’s Washington mission leadership, the SDC sees these political negotiations as a separate issue from military cooperation. The group’s military wing may cut deals with the Assad regime to let its troops into SDF-controlled areas, but that does not mean that they are interested in a broader political settlement on the Assad regime’s terms.

Policy Options

As Turkey ratchets up the pressure, the AANES will continue to lean increasingly on the Assad regime and its allies to meet its security needs. This, in turn, grants Damascus greater leverage over the Autonomous Administration, potentially leaving the regime with more capacity to pressure the AANES into political concessions it does not want to make. The Kremlin may aid the regime’s agenda as well: Russia has been consistently supportive of its efforts to consolidate control over the entire country, most notably during the regime’s ruthless 2021 offensive against armed opposition groups in Daraa, where Russia was ostensibly a neutral mediator but in reality pressured anti-regime groups to acquiesce to Damascus’s demands.

The United States cannot reverse these trends on its own, but there are some steps it could take to make the AANES less reliant on the Assad regime. Washington has thus far avoided weighing publicly on Turkish strikes against the SDF and civilians in northeast Syria. Public emphasis on the need for de-escalation and a diplomatic solution would raise the diplomatic costs of these strikes and may deter Turkey from intensifying the conflict further. Moreover, as the SDF becomes increasingly willing to retaliate, and claim credit for its attacks against Turkish forces, U.S. pressure on the SDF could also help break the recent trend of escalation along the front lines. Washington’s top priority should be persuading Ankara that this pressure is counterproductive to its own interests. Previous invasions failed to fragment, let alone destroy, the SDF, and there is no guarantee that even a successful campaign to force the group to retreat 30 kilometers from the Turkish border would do so either. Years of pressure have not succeeded in destroying the group, but they have succeeded in making it more reliant on the Assad regime and its allies. At a certain point, expanded Russian and regime presence east of the Euphrates may make U.S. presence there untenable, and the SDF would be forced to cut a more comprehensive deal, whether it wants to or not, with the regime.

Rather than defeating the SDF, Turkey’s current policy is likely to force the group into the Assad regime’s fold. At that point, the U.S. will not be able to vet the group’s use of Western-supplied material, enforce cease-fire terms, or effectively mediate in the event of future tensions between the group and Turkey. Turkey will be left with the same set of problems it set out to solve, but with fewer non-violent means to solve them.

U.S. security assistance to the SDF is already rigorously vetted, but Washington could work with Ankara to develop more robust procedures while reminding Turkey that this oversight would be lost if the United States were forced to pull out of the region. Unless Ankara can be persuaded that its own strategy to degrade the group is not in its best interests, present trends are likely to continue, with the SDF shifting incrementally toward Damascus even as a formal political settlement remains a remote possibility.

Calvin Wilder is an Analyst for the Nonstate Actors program at the New Lines Institute. Prior to joining the New Lines Institute, Calvin was a Research Assistant at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy’s Program on Arab Politics. He previously worked as a Research Assistant on the Chicago Project for Security and Threats (CPOST)’s Arabic Propaganda Analysis Team, and he was a Boren Scholar in Amman, Jordan from 2019-2020, working as a research and translation intern at Syria Direct. He holds a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science from the University of Chicago. He tweets at @CalvinWilder.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of the New Lines Institute.