The United States has important equities in Lebanon, including a desire for a generally friendly government’s economic and political stability; security cooperation; long-standing relations with the large Christian community in Lebanon and Lebanese diaspora in the United States; and ultimately peace between Israel and Lebanon within a broader regional settlement. Achieving these objectives will require navigating a tumultuous period in the country’s history following a war between Hezbollah and Israel that has devastated a large part of the country, exacerbating Lebanon’s already challenging economic conditions. But perhaps the most important dynamic will be how a likely Sunni-dominated state of uncertain composition in Syria will differ in its intentions toward Lebanon from the previous Alawite-led minoritarian Assad regime.

Syria is destined to play a profound role in Lebanon’s politics, for good or ill. If whoever rules securely in Damascus sees their counterparts in Lebanon as hostile or harmful, the latter cannot survive politically, and all too frequently, literally. On the other hand, if a Syrian government wants to grant a faction an advantage as it did Hezbollah, the faction will be well positioned to dominate Lebanese politics and security. This is the basic context for any U.S. policy in a post-Assad Lebanon.

Geopolitics and History

Even before the Assad regime’s rapid collapse, Lebanon presented a policy conundrum for the United States. For decades, U.S. policy sought to develop political and security equities there while simultaneously isolating and pressuring Hezbollah. The former was meant to support the latter, with the assumption being that it would be a slow process of building Lebanese state capacity while seeking to contain and shrink, the power of Hezbollah. Yet, in the span of less than a quarter of a year, Hezbollah has been cut from its patrons and its strategic depth in Syria through the violent overthrow of a friendly Syrian regime while still trying to recover from being decimated in war with Israel.

The old assumptions must change. Like everything of political importance in Lebanon, Hezbollah and its rivals have always been more profoundly shaped by what happens in Damascus than anyplace else. The fall of the Assad regime is the most monumental external shock to Lebanese politics since the 1969 Cairo Accord that provided a formal haven for the Palestinian militant groups that would set sectarian tensions to boil in the country, resulting in Lebanon’s civil war from 1975 to 1990.

Lebanon is surrounded by its hostile southern neighbor Israel, the Mediterranean Sea, and Syria, with whom it shares most of its land borders. Syria has been a major Lebanese trade partner and a haven for Lebanese escaping war. Its population dwarfs Lebanon’s. The last half-century has shown that whoever controls Syria can readily project military power into Lebanon and manipulate Lebanese public life. The history of Lebanon’s civil war is, in large part, one of the gradual establishment of Syrian control. Even Hafez al-Assad’s poor, isolated, and dysfunctional Syria was able to take over a complex polity like Lebanon in the 1970s, a period that ended in 2005 when his son and successor Bashar al-Assad was forced to withdraw his troops.

Over the past four decades, the United States’ main concern regarding Lebanon has been Syria’s longstanding support for Hezbollah. Although Hafez al-Assad’s troops fought sporadic battles against the party as he consolidated control of Lebanon in the late 1980s, the Syrian-backed peace treaty that ended the civil war in 1990 (the Taif Accord) made Hezbollah the only party permitted to retain arms for the stated purpose of fighting an Israeli occupation and formalized a “special relationship” between Lebanon and Syria. In the ensuing years, Hezbollah grew vastly more powerful, forcing other Lebanese to allow it to keep its militia even after Israeli troops left Lebanon in 2000.

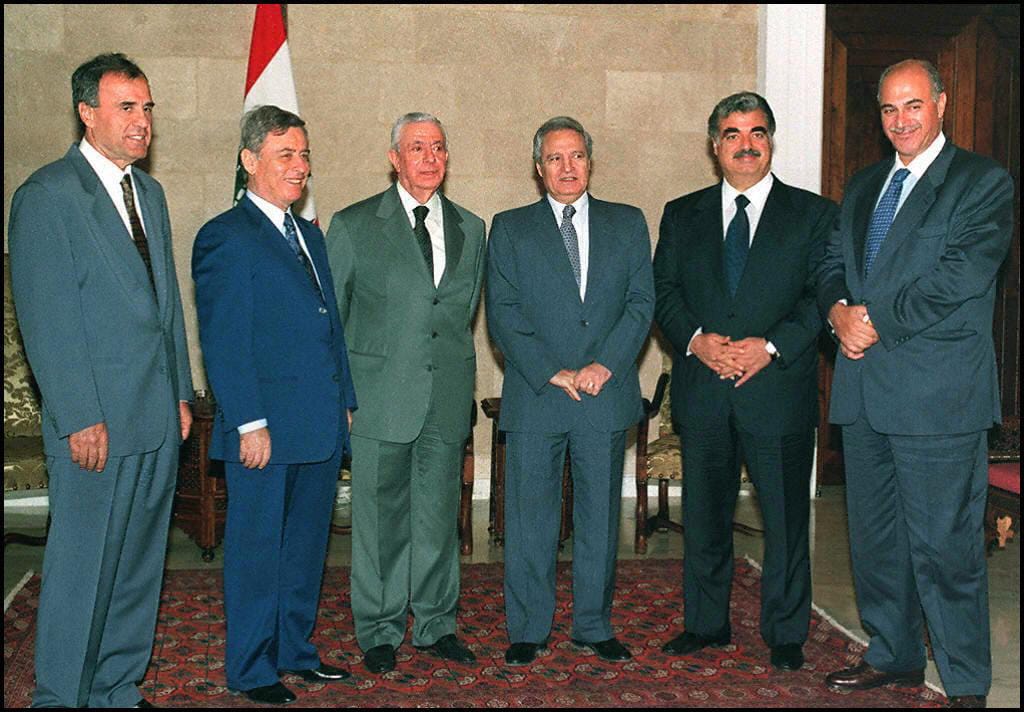

Toward the late 1990s, a small opposition movement began to emerge against a Syrian presence that had turned into a deeply corrupt racket bleeding the Lebanese economy and a police state punishing Lebanese who opposed the suffocating presence of Syria’s intelligence services. Following Hafez’s death in 2000, Bashar cracked down harder still on growing Lebanese opposition to the occupation. After Syria’s onetime protégé, Lebanese Prime Minister Rafik Hariri, joined that opposition after years of working with and enriching the Syrian occupation, in 2005 the Assad regime had him killed, followed by a series of other opposition figures. That the regime was able to kill such a high-profile, wealthy, and internationally connected figure and get away with it, demonstrated the inescapable fact of Syrian power in Lebanon. Although mass protests broke out after Hariri was killed and Syrian troops withdrew from Lebanon that same year, Syrian intelligence agencies and partner Hezbollah continued to kill Lebanese. Direct Syrian influence through its intelligence services, ended only after the regime became consumed by its own civil war in 2011.

Impact on Hezbollah

The Assad regime’s rapid fall will have several strategic implications, some more certain than others. Russian influence could fade, to the benefit of Turkish influence. The Islamic State may find opportunities it can exploit amid all the changes. The U.S.-backed, Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces could lose significant territory in northeastern Syria, and Jordan may cultivate allies in southern Syria. Ahmad al-Sharaa (also known as Abu Mohammed Al Jolani) and his former Al Qaeda-associated group and their foreign Salafist-Jihadist allies with a history of directly targeting Hezbollah inside of Lebanese territory may come to dominate politics. Or the opposite may happen as formal or real power devolves to different regions and parties. Or none of these might happen. But whoever controls Syria will likely be hostile to Hezbollah.

Hezbollah’s fate is the reason behind Iran’s decadelong and ultimately fruitless mission to save the regime in Syria. Iran recognized that Syria was crucial to protecting its crown jewel in Lebanon, knowing that whoever controls it has a strong influence on Hezbollah’s fate. The Iranian “land-bridge” that supplied Hezbollah through Syria is now destroyed. This supply line could survive in a Syria where authority is nonexistent but not in a Syria with a government that opposes Iran and Hezbollah, especially amid persistent Israeli airstrikes. Without this supply line, an isolated Hezbollah is forced to rely on Beirut’s much less efficient and more exposed airport and port, a devastating setback for the group as it tries to recover from its intense war with Israel.

Syria also offers crucial strategic depth for Hezbollah fighters and equipment during periods of Israeli pressure on the group in Lebanon. This has been somewhat blunted but not eliminated by the expansion of Israeli operations into Syria since Assad’s fall. The strategic depth also extends to the mostly-Shiite refugees displaced by wars with Israel who frequently escape into Syria. They may find themselves much less welcome in Syria due to their perceived support for Hezbollah, trapping them in Lebanon and straining the party’s standing among Lebanese Shiites during wartime.

The final threat to Hezbollah lies in any Syrian regime’s ability to target its fighters and assets in Lebanon through covert action, direct operations, or in cooperation with Lebanese security forces. While this may seem far-fetched at present, Syria has a history of killing Hezbollah members in Lebanon, and for the entirety of its occupation of Lebanon it placed strict limits on the group’s arsenal and capabilities. Syria may find willing accomplices in Lebanon given the widespread Lebanese hostility to the party.

Indeed, Lebanon’s Sunni-heavy Internal Security Forces (ISF) are already predisposed to counter Hezbollah when they can and could find a strong partner in Syria’s post-regime intelligence branches. It was an ISF officer, Wissam Eid, who first uncovered a Hezbollah cellular phone network used to coordinate Hariri’s assassination. This became key evidence in a U.N. tribunal to prosecute his killers. Eid himself was killed, almost certainly by Hezbollah. Wissam al Hassan, an ISF brigadier general and intelligence director, at one point headed the investigation into Hariri’s death and later aided the rebels in Syria when the civil war broke out. He was assassinated as well, again most probably by Hezbollah.

Impact on Lebanon

Syria will not soon reestablish full influence in Lebanon. Despite the wave of understandable optimism over Syria’s future, the complex and fragmented country remains burdened by a destroyed economy, weak institutions, and wary neighbors. It may be years before governing power is fully consolidated, and the country’s focus will mainly be fixed by its numerous problems. Syria may move toward a decentralized political model. Alternatively, it may once again plunge into civil war with profound effects in Lebanon. Nonetheless, whatever leadership emerges will likely be Sunni-dominated and hostile to the Shiite Hezbollah, ideologically and/or due to its wartime support for Assad’s regime and its subsequent atrocities against Syrians.

It is also possible a new Syrian government could provide a haven for Salafist-Jihadist foreign fighters who, along with local Syrian Salafist-Jihadists, could connect with Lebanon’s preexisting militant Salafist networks to wage war on Hezbollah in Lebanon. Although they do not form the majority of Lebanese Sunni opposition to Hezbollah, latent networks of militant Salafist fighters can be found in Tripoli, Akkar, and the Bekaa Valley. Such a partnership could present a security threat not only to Hezbollah but also to Lebanon’s tenuous sectarian social contract as well.

However, while it is quite possible that a Sunni-influenced government in Syria could favor Lebanon’s Sunnis, the reality is that it is unlikely to be that straightforward. There may be serious differences between the Sunnis governing Syria and the Sunnis of Lebanon, who have their own identity, specific historical experience, and varying attitudes toward Syria. Lebanese Sunnis could feel empowered by the Alawite regime’s defeat to increase their political and economic clout at the expense of other factions. Lebanon has a long history of such sectarian power plays, which usually involve one sect staffing sensitive institutions with its members, displaying strength and confidence through demonstrations, and even setting up sectarian militias to counter or augment influence in formal institutions. It is unwise to try to predict the effect of regime change on Lebanon based on sect alone.

There is also the issue of over 1 million Syrian refugees in Lebanon. One does not need to demonize refugees to recognize that this is a humanitarian and social burden that the weak and dysfunctional Lebanese state cannot bear, to say nothing of the refugees’ own desires to return home. While several factors drove refugees into Lebanon, the fighting in Syria and the Assad regime’s repression were the main ones. With relative peace and stability in a post-Assad Syria, they are most likely to seek to return.

Even just partial normalcy in Syria would greatly boost trade with Lebanon which relies heavily on overland transport and Syrian demand. It would almost certainly drive capital flows into Syria to fund reconstruction and other investments, although it is difficult for now to imagine revenues entering the Lebanese financial system, which remains devastated and under strict (improvised) capital controls. A more normal Syria would also benefit the many Lebanese with relatives in Syria who would once again be able to travel to and from there.

Over the longer term, anti-Hezbollah leadership in Syria would gradually consolidate its authority and boost its capacity to project power into Lebanon. This would extend Syrian hostility to Hezbollah beyond mere disruption of supply lines. A new Syrian government will likely deploy some of the same tactics as did its predecessor to shape Lebanon’s strategic environment. While Syrian actions in Lebanon would weaken Hezbollah, and could even destroy it, Syrian interests extend beyond Hezbollah. Syrian aims are as likely to include prosperity through free trade as they are to push for a friendly government in Beirut using manipulation, or force, if necessary, against an array of Lebanese actors and institutions.

Implications for Policy

There is a long-standing and basically sound U.S. consensus about what it wants from and in Lebanon: A government with a democratic mandate and sound economic fundamentals, exercising control over its territory and borders, and having a positive diplomatic and security relationship with the United States. Although the Hezbollah element understandably complicated this framing of U.S. interests, it has persisted and will be aided by the collapse of the Assad regime.

U.S. policy in Lebanon has long been distorted and tormented by the inability to reconcile boosting Lebanese sovereignty with Hezbollah’s presence. U.S. policy has therefore sought to isolate and sanction Hezbollah and support Israeli operations against the group. But it has done so while trying to dodge Hezbollah’s deep penetration of Lebanese institutions to cultivate relations with Lebanese politicians that share a cabinet and parliament with their Hezbollah rivals and to deepen ties to the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF), which contain pro-Hezbollah elements.

Detractors to this policy saw it as essentially aiding Hezbollah, given how embedded it was in the institutions the U.S. supported. These critics include influential officials in Washington. Of course, Israel draws no such distinction between Hezbollah and its context at all. Although the criticisms overly simplify the situation, the arguments contain some truth. However, this entire debate may have been rendered obsolete by regime change in Syria.

Absent an unlikely large-scale deployment of Iranian forces to Lebanon or Syria, Hezbollah in its current form cannot survive the confluence of steady, sustained Israeli military operations, Syrian hostility, and deep grievances among Lebanese. It could be reduced to another Lebanese militia with perhaps an advantage over others in armament and numbers but without the ability to shape Lebanese politics at will, control large parts of the Lebanese economy, or impact regional geopolitics. It is also likely to be the target of sustained harassment or worse at the hands of aggrieved Lebanese. This is not only due to its diminished strength but also because of the removal of the psychological fear barrier due to its humiliation at the hands of Israel.

The Assad regime’s collapse does not make Lebanon a clean, uncomplicated policy issue for the United States simply because it weakens Hezbollah. There remains the broader issue of Lebanon’s systemic corruption and factionalism that has caused the decay of its economy and governance while weakening its democracy. While Hezbollah was the guardian of this system, its disappearance would not solve these problems. None of this, however, changes the basic configuration of U.S. interests in Lebanon. Indeed, these problems only add urgency to a more expansive, robust U.S. policy in a post-Assad Lebanon.

The Takeaway

Although Syria and Lebanon today present a rapidly shifting environment, U.S. policy need not account for every variable, but it should begin to consider the reality that a new government in Syria will likely present a paradigm-shifting influence on the decision-making of Lebanese actors. Most of Hezbollah’s Lebanese rivals, in line with U.S. preferences, will likely seek to capitalize on and further exacerbate its weaknesses, diminishing their direct enemy. One succinct way to describe this line of effort would be to “minimize Hezbollah,” shrinking its capabilities as a military actor and limiting the economic spaces ̶̶ both formal and informal ̶̶ that it can leverage to its benefit as it seeks to rebuild.

The U.S.-brokered cease-fire between Israel and Hezbollah, while imperfect, serves to maintain pressure on Hezbollah and empower the LAF and should be interpreted and implemented expansively. This mechanism faced serious obstacles in isolation, but when coupled with the change in Syrian leadership it will endanger Hezbollah. An isolated Hezbollah is vulnerable to harassment by the military and its Lebanese opponents. Constant pressure can build on its deepening physical isolation. Hostile forces on the Syrian side of the border and an empowered LAF will complicate life for Hezbollah.

While a weak Hezbollah is in the U.S. interest, so is an independent, democratic, and friendly Lebanon. The United States should plan around many possibilities to that end, including an anti-Hezbollah Syrian role in Lebanon while also considering, perhaps, a more heavy-handed one that might undermine Lebanese sovereignty. This role may not be as harmful as that played by Assad’s paranoid, sectarian police state. A truly liberal, democratic Syrian government could indeed play a benign role in Lebanon. But planning should account for all possibilities, as a Lebanese government facing both a defensive Hezbollah and an interventionalist Syria may require greater U.S. backing.

The Middle East is a region whose deeply diverse peoples are profoundly interconnected both with one another and the rest of the world. It is also a pool of immense human capital and tremendous youthful energy waiting to be used to advance human development and growth. U.S. policy has tended to ignore this connectivity, seeing immediate security concerns as divorced from or even in tension with regional human security and prosperity. This approach flows from zero-sum thinking about U.S. security and the security of the region’s people, generating policies that harm both. This center aims to inform a U.S. policy that recognizes the connectivity of U.S. and regional security and prosperity, and the connectivity that ties the region’s people together and to the world.

Nicholas Heras is the Senior Director for the Strategy and Programs Unit in the Academic Division at the New Lines Institute. In this role, he develops strategic programming for the academic programs at the Institute and oversees the institutional research innovation activities. He was previously the Deputy Director of the Human Security Unit and the Senior Analyst and Program Head for the State Resilience and Fragility Program at the Institute. Before joining the institute, he was the Director of Government Relations and the Middle East Security Program Manager at the Institute for the Study of War, the Middle East Security Fellow and the 1LT Andrew J. Bacevich, Jr., USA Fellow at the Center for a New American Security, and a Senior Analyst at the Jamestown Foundation. He tweets at @NicholasAHeras.

Faysal Itani is a Senior Director at the New Lines Institute for Strategy and Policy. He is also an adjunct professor of Middle East politics at Georgetown University. Itani was born in and grew up in Beirut, Lebanon, and has lived and worked in several Middle East countries. Before joining the New Lines Institute, he was Senior Fellow at the Atlantic Council working on U.S. policy in the Middle East. He has been widely published and quoted in prominent media outlets including The New York Times, Time magazine, Politico, The Washington Post, CNN, U.S. News, Huffington Post, and The Wall Street Journal. He tweets at @faysalitani.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of the New Lines Institute.