Listen to article

On June 23, law enforcement officials at Kuwait’s International Airport identified suspicious cargo that had arrived from Turkey. The peculiar cargo contained thermal packaging machines that a Syrian national had submitted as air freight. Upon review, Kuwait’s General Administration of Customs identified an assortment of over 4 million dark brown, yellow, and white tablets of captagon, an illicit amphetamine-type substance, expertly hidden beneath the machine’s scanners.

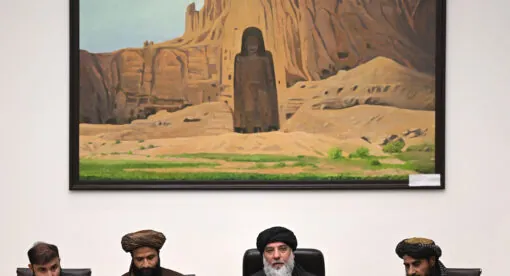

While Kuwaiti customs were undertaking this major captagon seizure, the country’s law enforcement representatives convened in a conference room in the UAE for an INTERPOL-sponsored discussion of regional efforts to combat local drug trades. Coincidentally, the Kuwaiti representatives sat across the room from two representatives of the Syrian government — the primary agent behind the modern-day captagon trade.

With a surge in captagon shipments across the region, the conference came at an appropriate time. Regional drug traffickers have become more sophisticated, innovative, and even violent in their smuggling operations, while consumption of illicit drugs like captagon, tramadol, and methamphetamine are reaching alarming rates, creating a greater need for regional dialogue and cooperation over supply and demand reduction. However, the inclusion of the Syrian government in sensitive INTERPOL conversations about collaborative efforts to stave illicit drug trades is counterproductive to those efforts. Including the Syrian government gives Damascus a platform to deny involvement in the captagon trade and arms it with the necessary intelligence to stay one step ahead of transit and destination countries.

Captagon’s Anchor: Regime-Controlled Syria

Since 2019, evidence linking the captagon trade with actors closely aligned with the upper echelons of the Syrian regime and partnered armed groups loyal to Iran has continued to accumulate. Investigations, reports, and analyses revealing new intelligence about the captagon trade conducted by the New Lines Institute, Der Spiegel, The New York Times, Radio France Internationale, Center for Operational Analysis and Research, and others, have gathered evidence of ministry-level participation and complicity in the production and trafficking of captagon. Contributing to the captagon trade’s momentum are multiple layers of militant groups such as the Fourth Armored Division closely aligned with the Syrian regime’s security apparatus, private sector businessmen and shell companies close to the Syrian government, and even relatives of Bashar Al-Assad. These actors oversee captagon production sites in Latakia, Aleppo, Homs, Da’ara, and regime-controlled points along the M4 highway; offer transportation, materials, and personnel for smuggling operations; and provide agricultural produce, industrial goods, and other licit products for concealing captagon pills.

As evidence about state-level complicity and participation in the captagon trade has accumulated, the Syrian regime has conducted a series of cosmetic reforms, a public awareness campaign, and occasional seizures to reduce visible signs of participation. These policies have been designed to deflect blame amid regional accusations and create a narrative that it is serious about cracking down on crime. With mounting allegations of state-level participation in captagon manufacturing and trafficking, the Syrian Interior Ministry marked World Anti-Drug Day on June 26 with a national seminar in Damascus for ministers, police chiefs, and practitioners. At the seminar, National Narcotics Commission leader Minister Maj.-Gen. Mohamed Rahmoun and Youth of the Revolutionary Union President Sumer Al-Dahir reaffirmed that Syria has played an important role in supporting the international community’s efforts to combat narcotics. The Interior Ministry additionally announced that it was launching a series of patrols to combat drug smuggling operations along with a public awareness campaign comprising anti-drug informational videos warning the risks of drug consumption with the catchphrase “NO TO DRUGS, YES FOR LIFE.”

In recent months, there has been an uptick in reported captagon seizures in regime-held areas; however, these interceptions are disproportionately small-scale and target individuals. Large-scale shipments meant for destination markets in the Persian Gulf region and often orchestrated by regime-aligned forces and criminal networks are rarely seized. Additionally, some of the Interior Ministry’s announcements describe the seized substances in vague terms, such as “foreign medicine,” “narcotics,” or “drugs,” rather than captagon. The sudden spike in regime-conducted interdictions coincided not only with the June INTERPOL conference on Operation Lionfish, but also with additional opportunities for face-saving measures: the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime’s International Day Against Drug Abuse and Illicit Trafficking, a weekend-long Arab League Meeting in Beirut at the end of the month, and rapprochement efforts with several Middle Eastern governments.

Despite continued pleas and signs of agitation from neighboring transit and destination countries, Damascus has done little to pump the brakes on the pace of smuggling operations from Syria or temper the violent behavior of regime-affiliated armed smugglers. While the government continues to publicly deny participation in the trade, it has done little to restrict clashes — some fatal — perpetrated by smugglers from Syria along the country’s border with Jordan. Some of these smugglers have reportedly had strong links to the Syrian regime’s Fourth Division and aligned partners such as Hezbollah and Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps-backed militias. These actors smuggle large amounts of captagon tablets, many produced on an industrial scale within regime-held areas. And with a stream of Russian reinforcements and renewed operational focus in the country’s north amid signs of a potential Turkish intervention, there will be greater space for Syrian Fourth Division forces, Hezbollah, and partnered Iran-aligned militias to facilitate the flow of illicit goods in the country’s south.

Syria’s Reintegration into INTERPOL

In the months leading up to the June conference, Syria had been gradually reintegrating into INTERPOL while pursuing normalization efforts with key Gulf actors like the UAE. In 2012, INTERPOL’s Executive Committee applied corrective measures on Syria’s National Census Bureau in Damascus, effectively cutting the Syrian regime off from its informational system that allowed the country to work directly with international police, share intelligence, and issue arrest warrants for individuals abroad. Yet, after nearly 10 years of Syria being on the outs with INTERPOL’s information system, INTERPOL’s Executive Committee made the decision to lift these restrictions in June 2021. By Oct. 2, 2021, Syria was back in the fold, with renewed access to INTERPOL’s informational channels and notification system, and an INTERPOL team providing training to the census bureau in Damascus.

INTERPOL’s 2021 decision to reintegrate and lift corrective measures on the Syrian government incited concerns about the implications and potential abuse of the organization’s alert system. With revived access, Syria could utilize INTERPOL’s “Red Notice” notification system to issue arrest warrants and track and prosecute exiled opposition figures and displaced Syrians abroad. Additionally, Syria could utilize INTERPOL’s more informal diffusion systems— a process that notably has less accountability, given a lack of internal screening for politically motivated warrants. INTERPOL defended its decision to welcome Damascus back into the fold, stating it could not constitutionally exclude Syria on political grounds and that Syria had, over time, demonstrated better data processing capabilities.

And now, months after Syria’s re-accession into INTERPOL’s notification system, INTERPOL took a new step that raised Syria’s profile in the organization and increased its access to informational exchange, intelligence sharing, monitoring efforts, and planning for countering illicit trades and criminal organizations. Complemented by UAE-Syrian normalization efforts, INTERPOL extended invitations to a Syrian governmental delegation to discuss Operation Lionfish — a key INTERPOL effort aimed at disrupting the captagon trade in the Middle East and beyond.

A New Concern: Syria’s Access to Captagon Interdiction Efforts

Syria’s 2021 reintegration into INTERPOL’s notification system has sparked anxiety over potential abuses of politically motivated arrest warrants. However, the potential for the Syrian regime’s access to counter-narcotics efforts — particularly those seeking to curb the captagon trade — should be of equal concern as the Syrian regime enhances its engagement with INTERPOL. Syria’s invitation to the INTERPOL-sponsored and UAE-hosted conference on countering regional narcotics trades raises questions about increased Syrian governmental participation in interdiction efforts related to INTERPOL’s Operation Lionfish, as well as the organization’s project AMEAP (Africa, Middle East, and Asia and the Pacific) that offers countries operational and investigative support with INTERPOL global police databases.

It’s important that the U.S. and its partners heavily affected by the captagon trade in southern Europe, Africa, and the Middle East recognize this trajectory of Syria-INTERPOL engagement and establish alternatives for regional cooperation and dialogue for interdiction, all beyond the gaze of the Syrian government. As the captagon trade swells in the Mediterranean-Gulf zone, there is a greater need for a formal or informal mechanism between captagon’s transit and destination countries. Such a mechanism should promote not only cooperation and intelligence sharing over interdiction efforts, but also dialogue about strategies to target captagon supply, harm reduction, rehabilitative care, maritime and overland route monitoring efforts, and laboratory analysis and data collection for captagon tablets’ chemical composition.

Offering the Syrian regime a seat (or two) at the table in discussions about intelligence sharing, interdiction capacity, detection technologies, and monitoring efforts is counterproductive to the regional effort to manage the captagon trade. Doing so strengthens Damascus’ hand, allowing regime-aligned producers and traffickers in the Fourth Division and Syria’s private sector to adapt, identifying creative smuggling materials, transportation methods, new routes, and tactics to stay ahead of regional interdiction efforts.

Caroline Rose is a Senior Analyst and Head of the Strategic Vacuums program in the Human Security unit at New Lines. Her commentary and work on geopolitics and Middle Eastern affairs have been featured in Foreign Policy, The Independent, Alhurra, Limes Magazine, and the Atlantic Council’s MENASource. She tweets at @CarolineRose8.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of the New Lines Institute.