Captagon Production Proliferation in the Middle East: Transformations, Challenges, and Policy Responses

For over a decade, the Syrian regime under President Bashar al-Assad, alongside actors in Lebanon, served as the primary hub for captagon production and trafficking, exploiting it as a vital source of revenue and a tool of political leverage. However, captagon production over the past four years has been spreading well beyond its traditional zone, with wide-ranging policy implications.

Following Assad’s downfall, the shortfall in supply is being picked up elsewhere, with fragile countries such as Yemen and Sudan as strong candidates. Encouraged by steady demand the spread of expertise, and ease of production in makeshift facilities, captagon has been appearing in and near consumer markets.

This report is based on data from the New Lines Institute’s database at the Special Project on the Captagon Trade, which has documented over 1,800 incidents over the past decade. The database uses open-source tools to document operations relating to smuggling, production, storage, and arrests.

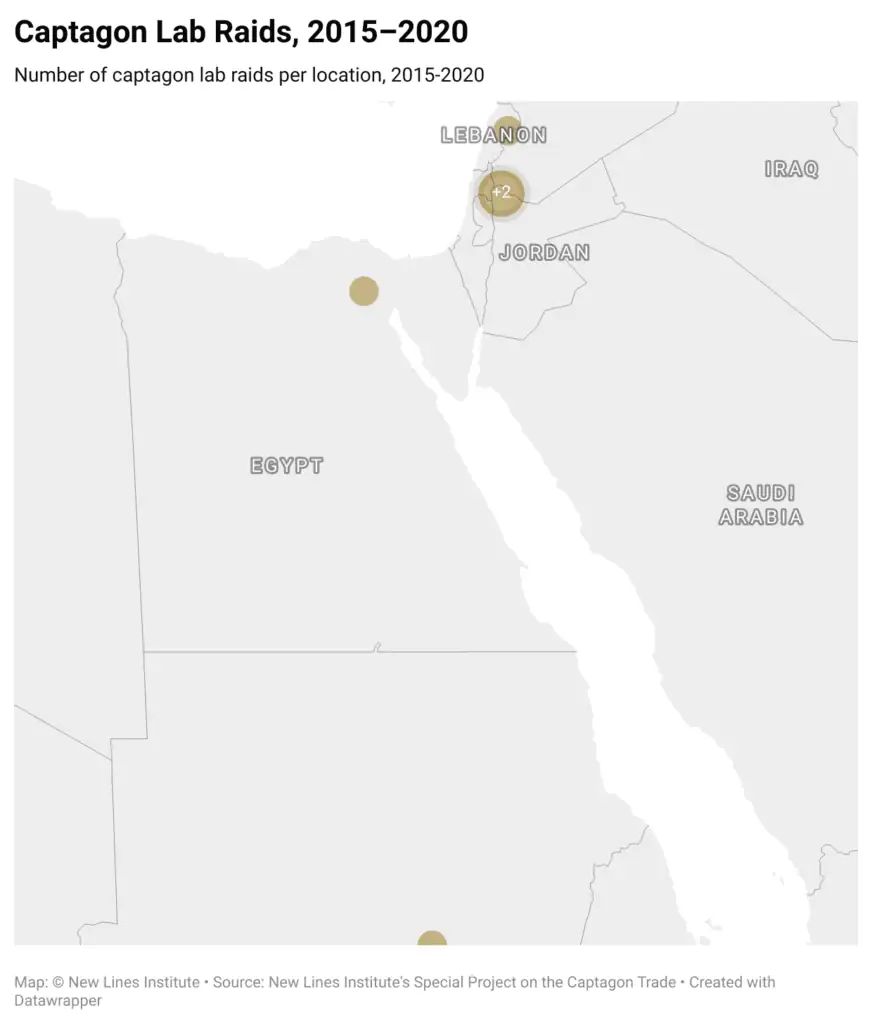

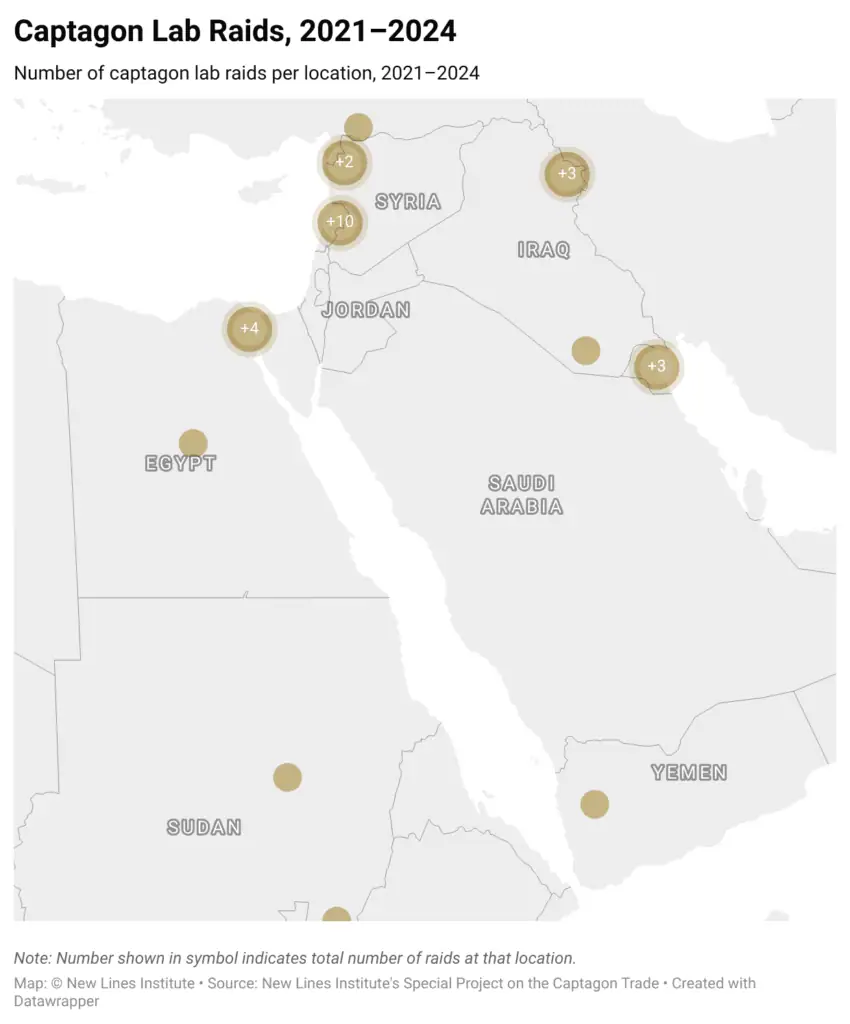

Comparison of Captagon Laboratory Raids: 2015–2020 (image on the right) vs. 2021–2024 (image on the left) — Data from the

New Lines Interactive Counter Captagon Dashboard.

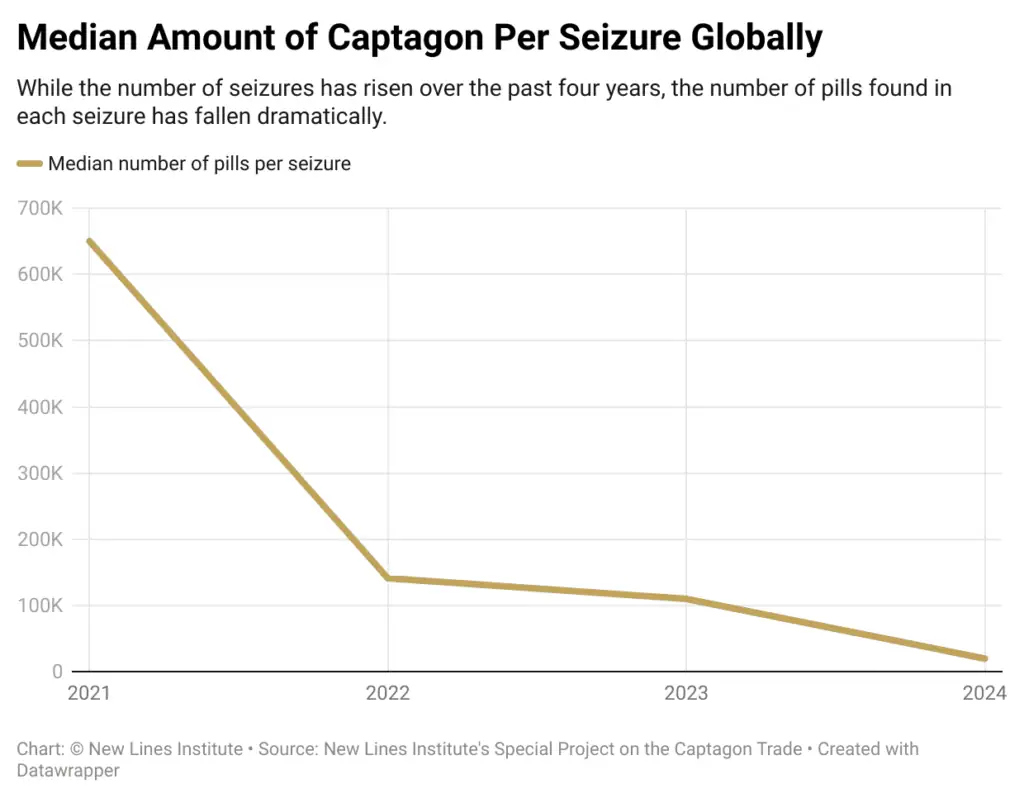

Fragmentation and Declining Seizure Sizes

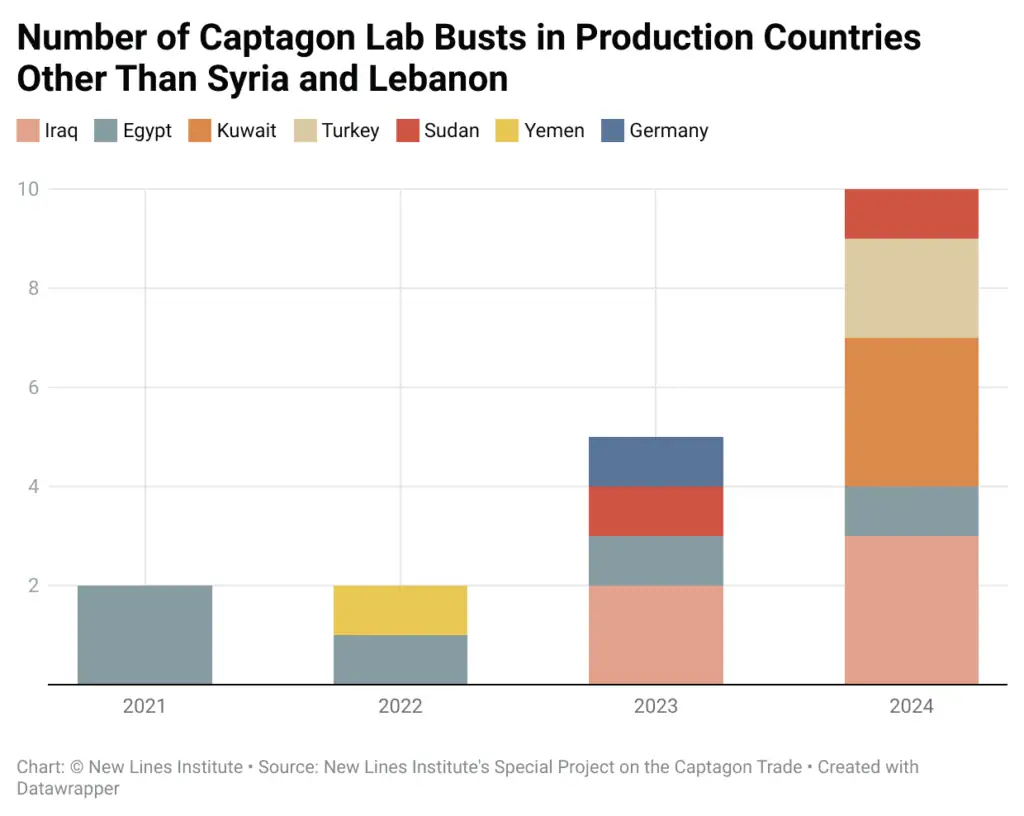

The increase in captagon lab busts outside Syria and Lebanon between 2021 and Assad’s downfall in late 2024 has not corresponded with a rise in overall supply, proxied by overall seizures. On the contrary, despite a record number of seizures in 2024, the average size of each shipment declined steeply, leading to a drop in the total volume of seized captagon, particularly in major consumption hubs like the UAE and Saudi Arabia.

Source: Author’s calculations based on data from the New Lines Captagon Trade Projec.

This suggests a shift toward smaller-scale production operations. The Assad regime provided state sponsorship, security coverage, and access to raw materials that facilitated industrial production, the true scale of which was revealed following its downfall. In the first four months of 2025, the new caretaker government in Syria seized over 200 million pills from production facilities and warehouses, including military installations, which is 20 times the amount Assad’s forces seized in all of 2024.

In contrast, emerging suppliers in other countries often lack such political support and established networks. This absence makes it difficult for new producers to obtain necessary inputs and produce without attracting law enforcement attention, driving a strategy of more frequent, smaller shipments to evade detection. However, the risk of industrial production popping up in other fragile countries in the region, such as Yemen and Sudan, especially given the likely significant supply gap left by the end of the Assad regime, is higher than ever. The expertise in captagon production, already spread across the region, might be spurred by Syrian criminal syndicates fleeing Damascus’s crackdown on their operations. Such relocation seems to be already in motion in Yemen, according to an interview with the Col. Khaled Eid, head of the Counter Narcotics Directorate in Syria.

Source: Author’s calculations based on data from the New Lines Captagon Trade Project.

Egypt

In Egypt, explicit captagon production facilities have emerged since 2021. In 2021, a captagon production factory was discovered on a remote farm in Ismailia, leading to the arrest of 10 individuals. That same year, a second facility was seized in Sharqia Governorate, where three individuals were arrested for their roles in manufacturing and exporting captagon, and authorities confiscated 505,000 pills along with 800 kilograms of captagon. The trend continued into 2022, with the arrest of two individuals specializing in narcotic drug manufacturing, including captagon, in 10th of Ramadan City. Further signaling local production, a “captagon manufacturing gang” was arrested in Cairo in 2023 with chemical components, and an individual was arrested for money laundering derived from captagon manufacturing. As recently as 2024, a gang involved in drug production and smuggling, including captagon, was busted.

This emergence of domestic production has corresponded with significant law enforcement efforts and arrests. Beyond the specific arrests tied to the lab busts, Egyptian authorities have made numerous other captagon-related arrests, indicating heightened criminality. For instance, a Syrian smuggler was arrested in Giza in possession of 1 million captagon pills, and two women were apprehended at Cairo International Airport attempting to smuggle 2 kilograms of captagon pills. Other busts include the arrest of a criminal element with 100,000 captagon pills in Abu Kibir, nine individuals caught with a large quantity of captagon in El Shorouk, and 10 individuals arrested in Dakahlia for planning to smuggle 32,500 captagon pills out of the country.

Iraq

Captagon production hubs have emerged in Iraq’s north and south over the past four years, moving beyond its previous role as primarily a transit country, with the most recent string of lab seizures in the Kurdistan Region. The first captagon lab in Iraq was discovered in Muthanna in 2023. This was followed by lab busts in Sulaymaniyah in 2024 and another run by Patriotic Union of Kurdistan leaders seized in Aawbar Village in 2024. An additional attempt to establish a factory in Muthanna was thwarted in 2024.

The emergence of this local production has coincided with increased law enforcement activity and severe repercussions for those involved. Iraqi authorities have made numerous arrests of drug dealers and traffickers, particularly in provinces like Anbar, Dhi Qar, and Babylon, often seizing large quantities of pills. The scale of criminality is highlighted by significant seizures, such as 17,500 kilograms of captagon pills found hidden underground in Anbar in 2024. The response to this illicit activity has been stringent, with reports of the “execution of four drug dealers” in Anbar and a “life sentence” issued against a drug dealer for captagon possession. While numerous captagon shipments originating from Syria have been intercepted entering Iraq, the provided sources do not explicitly mention the involvement of Syrian nationals in the actual manufacturing facilities or local production networks that have been busted within Iraq. Iraq launched a new National Drug Control Center in Baghdad in 2024 to enhance cooperation and intelligence exchange. However, it remains unclear how the center operates currently and how it influences Iraq’s regional cooperation.

Sudan

Sudan has transitioned into a captagon production hub since 2021, a shift dramatically accelerated by the ongoing civil war. The conflict has shattered state authority, creating a power vacuum and lawless environment where illicit economies can flourish. This breakdown provides armed groups, particularly the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), with both the operational freedom and the financial incentive to engage in drug manufacturing as a means to fund their war efforts. A factory dedicated to the production of captagon pills was successfully seized in the Blue Nile region in June 2023.

This burgeoning local production is strategically positioned to exploit Sudan’s proximity to the lucrative Gulf markets. With a long and difficult-to-patrol coastline, the country offers smugglers a direct and efficient transport corridor across the Red Sea to consumers in Saudi Arabia and beyond. The emergence of this local production has coincided with increased law enforcement activity and arrests. For instance, a seizure of 2.5 million captagon pills on a farm in Shendi in 2023 resulted in the apprehension of a foreign suspect. Other arrests of drug dealers and individuals possessing captagon have been reported in various locations, including Red Sea State and Wadi Halfa.

Given the precarious military situation in the country, the existence of know-how, proximity to the largest consumer market in Saudi Arabia, and the gap in supply left by the downfall of the Assad regime, Sudan might soon emerge as the main hub for production.

Kuwait

Since 2021, Kuwait has shifted away from primarily being a transit point toward becoming a site for captagon production. This emergence is evidenced by the discovery and dismantling of a sophisticated drug manufacturing laboratory in a remote desert area in northern Kuwait in 2024. Furthermore, a trafficker was arrested in 2024 in possession of a significant quantity of captagon pills, raw materials, and a press used to manufacture the drug, explicitly confirming local production capability. Another seizure in 2024, while primarily focused on Lyrica, also found captagon tablets at a secret factory, suggesting multi-drug manufacturing or at least the presence of captagon in a production context.

Other arrests involve individuals apprehended for smuggling captagon. Such cases include moving 2,000 captagon tablets by sea, and busting criminal gangs – some involving Kuwaiti and illegal Asian residents – for drug trafficking and smuggling. A notable arrest in 2024 involved a trafficker caught with 1 million captagon pills and the necessary production equipment. highlighting the scale of these operations and the authorities’ success in disrupting them.

Türkiye

Türkiye has notably transitioned into a site for captagon production since 2021, moving beyond its traditional role primarily as a transit country. This shift is evidenced by the discovery and dismantling of the first explicit captagon laboratory in Gaziantep in 2024. During this operation, Turkish police and intelligence seized 193,000 captagon pills, a press, and 79 kilograms of raw materials.

The emergence of domestic production and continued illicit trafficking has led to heightened criminality, as proxied by numerous arrests. Turkish authorities have conducted extensive operations across various cities, leading to the apprehension of many suspects and the seizure of substantial quantities of captagon pills, often accompanied by weapons. Specifically regarding Syrian involvement, a 2022 seizure in Istanbul resulted in the arrest of three individuals, including two Syrian nationals and one Lebanese national, illustrating the role of cross-border criminal syndicates.

Yemen

In Yemen, a rise in captagon-related activity has been witnessed over the past two years. However, following Assad’s downfall, the pace picked up considerably. According to our database, 400,000 pills were seized in or originated from Yemen in 2024, which increased to 5.4 million in the first nine months of 2025. Saudi Arabia, the nearest and most lucrative market, has been hit the hardest, intercepting four seizures in 2025 relative to just one in 2024. Early signs suggest al-Houthi rebels might be involved in the industry, though the extent of their involvement is not entirely clear.

Germany

In 2023, Germany’s largest captagon manufacturing facility was shut down in Regensburg. It had been run by two Syrian nationals who intended to distribute captagon internationally. Then in July 2025, police in eastern Germany announced the discovery of 1.7 million pills hidden in delivery pallets at a grocer, reportedly one of the biggest amphetamine busts in the country. The seizure might signal that Syria-based criminal organizations that engaged in the captagon trade under the Assad regime are seeking to export hidden stockpiles of captagon out of Syria quickly to dodge interdiction, using existing criminal alliances with EU-based groups to re-transport the consignments to destination markets.

Implications

The proliferation of captagon production may reduce prices and profitability in the long run, but supply disruptions following the collapse of Syria’s industrial network have caused price spikes in some markets. With Syria’s interim government cracking down on domestic facilities, production is increasingly shifting to fragile states like Sudan and Yemen, where weak governance enables industrial-scale operations.

As competition intensifies, especially in fragile security contexts, the trade is likely to become more violent, with rival groups vying for control over routes and markets. This has been seen at the Syrian-Lebanese border following Assad’s downfall in late 2024 and early 2025, causing captagon syndicates to scramble for safety and clear their remaining stockpiles, triggering a sharp and violent spike in smuggling and turf wars along the border. The initial post-Assad period between February and March 2025 saw intense clashes and casualties, especially in smuggling hotspots like the Beqaa Valley. However, recent, coordinated security operations building on the January joint-border security agreement by the new Syrian government and Lebanese Armed Forces have cracked down on the traffickers. These efforts have quelled the fighting and restored a fragile stability to the border region.

Restricted captagon supply may prompt a shift toward methamphetamine production, increasing addiction risks. The inconsistent composition of illicit pills is likely to get even more diverse with the emergence of new producers, further complicating treatment efforts. Overburdened health systems – particularly in Iraq – are ill-equipped to address rising stimulant dependency.

Smaller, mobile labs are harder to detect than the large Syrian facilities they replace. Traffickers are adopting new methods to avoid detection, straining already under-resourced enforcement bodies. In countries lacking robust drug control infrastructure, coordinating effective responses remains a major challenge.

Recommendations

Regional and international coordination: A regionally led mechanism on synthetic drugs, involving the interim Syrian government and international partners, should coordinate intelligence, operations, and policy. The U.S. can champion an amphetamine-focused working group under the Global Coalition Against Synthetic Drugs, or by activating and modifying the already-existing counter-captagon strategy requested by Congress in 2022 and announced by the State Department in 2023.

The U.S. government’s strategy to dismantle Assad’s captagon trade is a coordinated interagency effort that avoids direct military action. It focused on using diplomatic and intelligence support to aid law enforcement, imposing economic sanctions on traffickers, and providing training and assistance to partner countries like Jordan and Lebanon.

The core of the strategy was to apply financial and diplomatic pressure on the Assad regime and its networks while the U.S. military’s mission in Syria remains strictly focused on combating ISIS. However, considering the downfall of the Assad regime, the strategy needs to be revised, instead providing direct support to the interim government. Anchored in regional support and ownership, joint efforts should include intelligence sharing, lab analysis, and seizure data sharing to monitor evolving networks.

Capacity building for the new Syrian government: Syria’s interim authorities need support to secure borders, dismantle production sites safely, and manage chemical waste. International partners should also promote licit economic alternatives, including sanctions relief and small-business development, to undercut local reliance on the drug trade.

Demand reduction and public health: Efforts to reduce demand for captagon must prioritize comprehensive public health strategies. Awareness campaigns should be culturally sensitive and specifically designed to reach vulnerable populations such as youth, displaced persons, and those in conflict zones. In parallel, access to tailored rehabilitation programs must be expanded, even in conservative or resource-limited settings. Despite social or political constraints, harm reduction services such as counseling, community outreach, and non-punitive support should be scaled up to confront the growing challenges posed by captagon use.

Targeting and enforcement: Focus enforcement on high-level actors – financiers, suppliers, and logisticians – rather than street-level dealers. U.S., U.K., and EU sanctions should be better harmonized, with shared listings and evidence. Border control strategies like Jordan’s sensor-based fencing and kinetic deterrence can serve as regional models.

Acknowledgments

This article has benefited from the support of research assistants Shereen Shekho and Jaber al-Kasem.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of New Lines Institute.