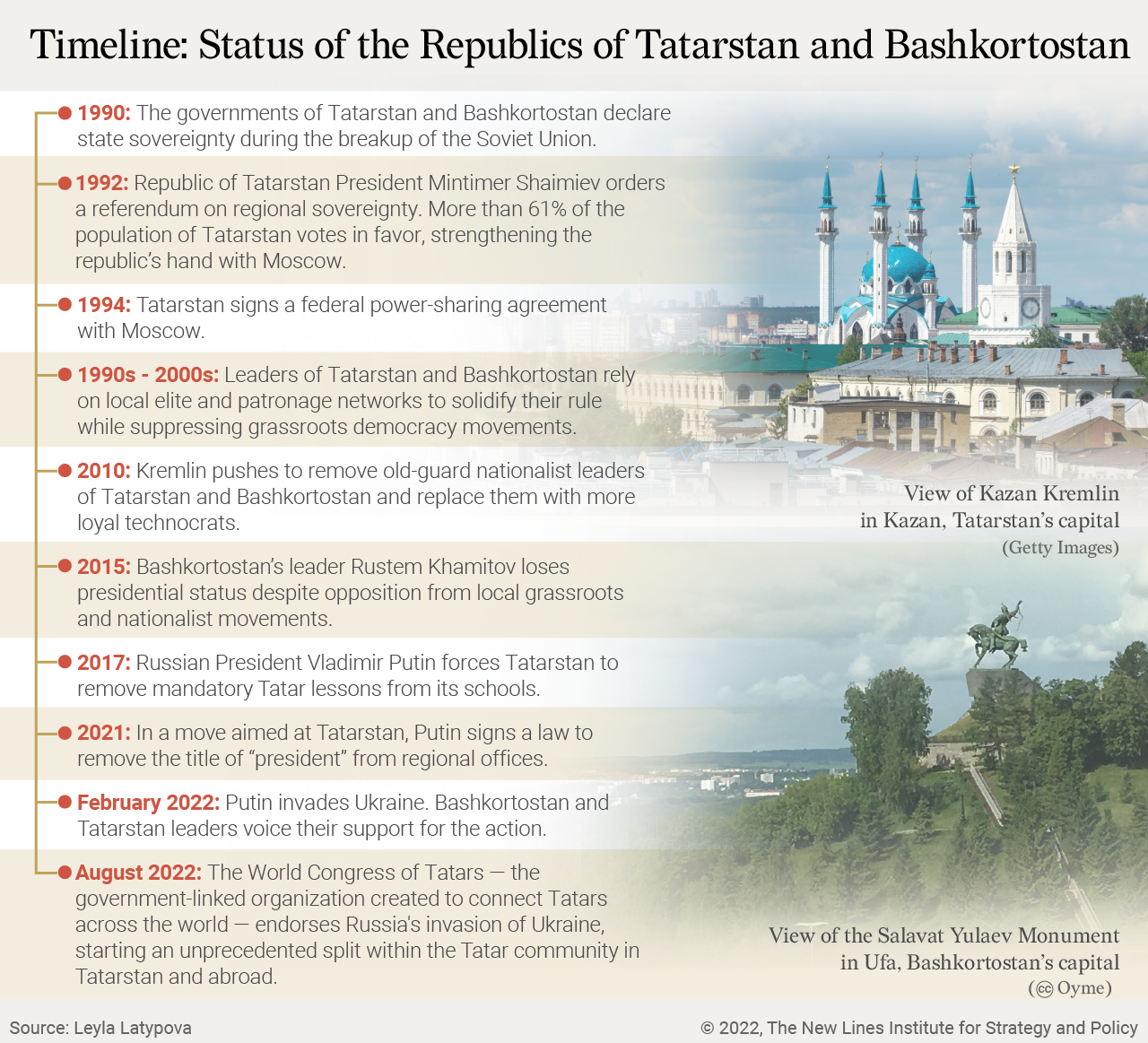

When Russian President Vladimir Putin signed the law that would rid Rustam Minnikhanov, the current leader of Tatarstan, of his presidential status in December 2021, most were puzzled by the unforeseen decision that was initially met with a backlash in Tatarstan. The Muslim-majority region was the last of the Russian Federation’s 21 republics to retain the special title of its leader and the arrangement was even greenlighted by Putin himself in 2015.

Now, with an understanding that the Kremlin has been long preparing for the offensive in Ukraine — which historian Timothy Snyder has rightfully labeled “a colonial war” — the logic informing Moscow’s action vis-a-vis Tatarstan is crystal clear: The Russian “empire” may only have one president. The traces of imperial past that are still well preserved in Tatarstan’s own historical narrative, and what the Kremlin sees as the ever-looming threat of growing affection for Pan-Turkic ideals among Tatar elites, make it even clearer why Putin rushed to demote Tatarstan into an “ordinary” Russian region, fully subjected to Moscow’s control, before the start of the invasion.

Putin’s regime has long pursued the vigorous centralization of power and erasure of non-ethnically-Russian cultures and collective identities found within the country’s current borders. The latter has been effectively performed by modifying mainstream historical narratives in the imperial core’s favor and excluding indigenous languages from education and daily life, among other practices. At the same time, Moscow’s 1994-1996 and 1999-2009 military campaigns in Chechnya — which were marked by numerous atrocities committed by the Russian army — are the most salient example of the Kremlin’s quest for greater grip on power.

While residents of Chechnya took up arms and lost countless lives in their fight for the right to self-determination and survival of their nation, several other “ethnic republics” chose to enter into a protracted legal and political stand-off with the Kremlin in an attempt to preserve their right to greater sovereignty enshrined in Russia’s 1993 constitution and a series of federal treaties negotiated under the Yeltsin administration. Bashkortostan and Tatarstan, the two republics located in Russia’s Volga-Ural region, have arguably sustained that fight the longest, though Tatarstan’s regional presidency was the last vestige of their autonomy to be erased by Moscow.

By bringing into sharper focus the colonial undertones of Moscow’s rhetoric and actions at home and abroad, the ongoing war in Ukraine has answered a question that experts in democratization and post-Soviet studies have grappled with for decades: Why didn’t Russia’s democratic project work? The reason is that internal and external actors alike, while paying attention to Moscow proper, have done little to aid the development of democratic governance and civil society at the regional level. In Tatarstan and Bashkortostan, regional actors across the political spectrum have long retained a strong will to stand up to the Kremlin’s ever-more-assertive attempts at centralization of power and Russification but often lacked the necessary leverage, readily available bargaining tools, and civic education at the grassroots level to act effectively.

On the federal level, the ever-growing centralization of power not only went hand in hand with Russia’s all-around democratic backsliding but also allowed for the greater exclusion of Russia’s ethnic minority groups from decision-making. The absence of non-Russian voices from federal politics allowed Putin to solidify the narrative of ethnic Russian exceptionalism and fostered the normalization of outward discriminatory practices against “lower-ranked” minorities across the country.

The path to solving the so-called “Russia problem” must start with paying greater attention to the country’s regions and ethnic minority groups as opposed to focusing solely on the Kremlin and ethnically Russian political and civil society actors. U.S. and allied policymakers should cease viewing the country as a monolithic entity and look to establish direct diplomatic and economic channels with existing regional governments, while also working to amplify the voices of regional democratic opposition activists advocating for stronger federalism and support their plans for the development of regional democratic projects.

In considering the viability and development of such policies, the U.S. should look at the example of its NATO ally, Turkey. For more than three decades now, the Turkish government has maintained direct diplomatic and trade relations with the republic of Tatarstan. Ankara and Kazan didn’t cease cooperation even during the 2015 Russo-Turkish crisis, when Tatarstan’s government noticeably avoided siding with the Kremlin and remained Turkey’s loyal ally and partner. Since the 1990s, Turkey has heavily invested not only in developing bilateral trade with Tatarstan but also in bolstering its soft power in the region by creating educational exchange programs, region-specific humanitarian initiatives, and Turkish-sponsored elite educational institutions that worked to prepare the new generation of politically and civically active Tatar intelligentsia.

Turkey’s strategy of working directly with Russia’s regions didn’t end with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, in fact, the Turkish government seems to be ever more determined to foster relations with regional actors. In June, Turkish officials voiced their intention to open an Honorary Consulate of Turkey in Bashkortostan.

Some Autonomy, Little Democracy

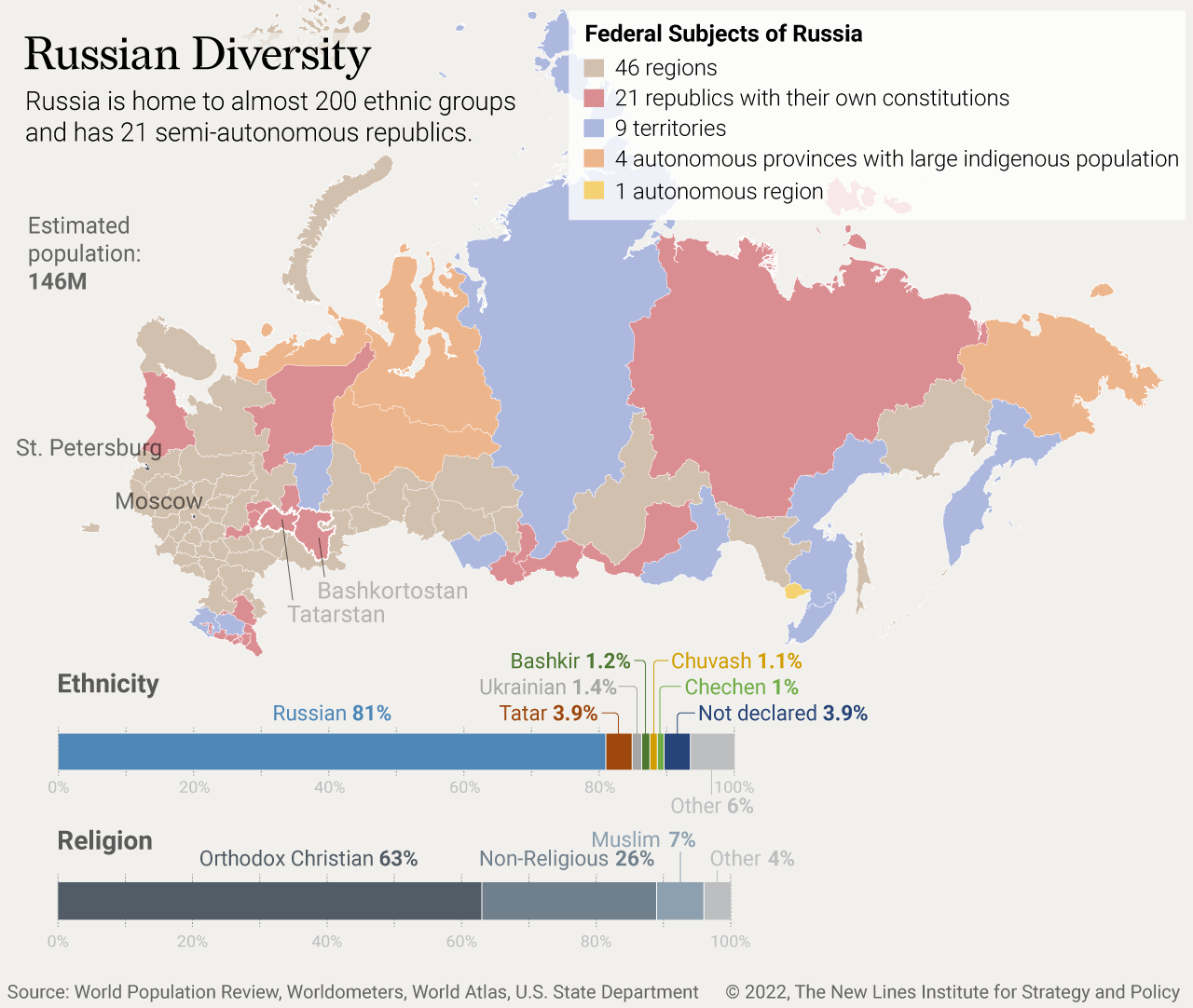

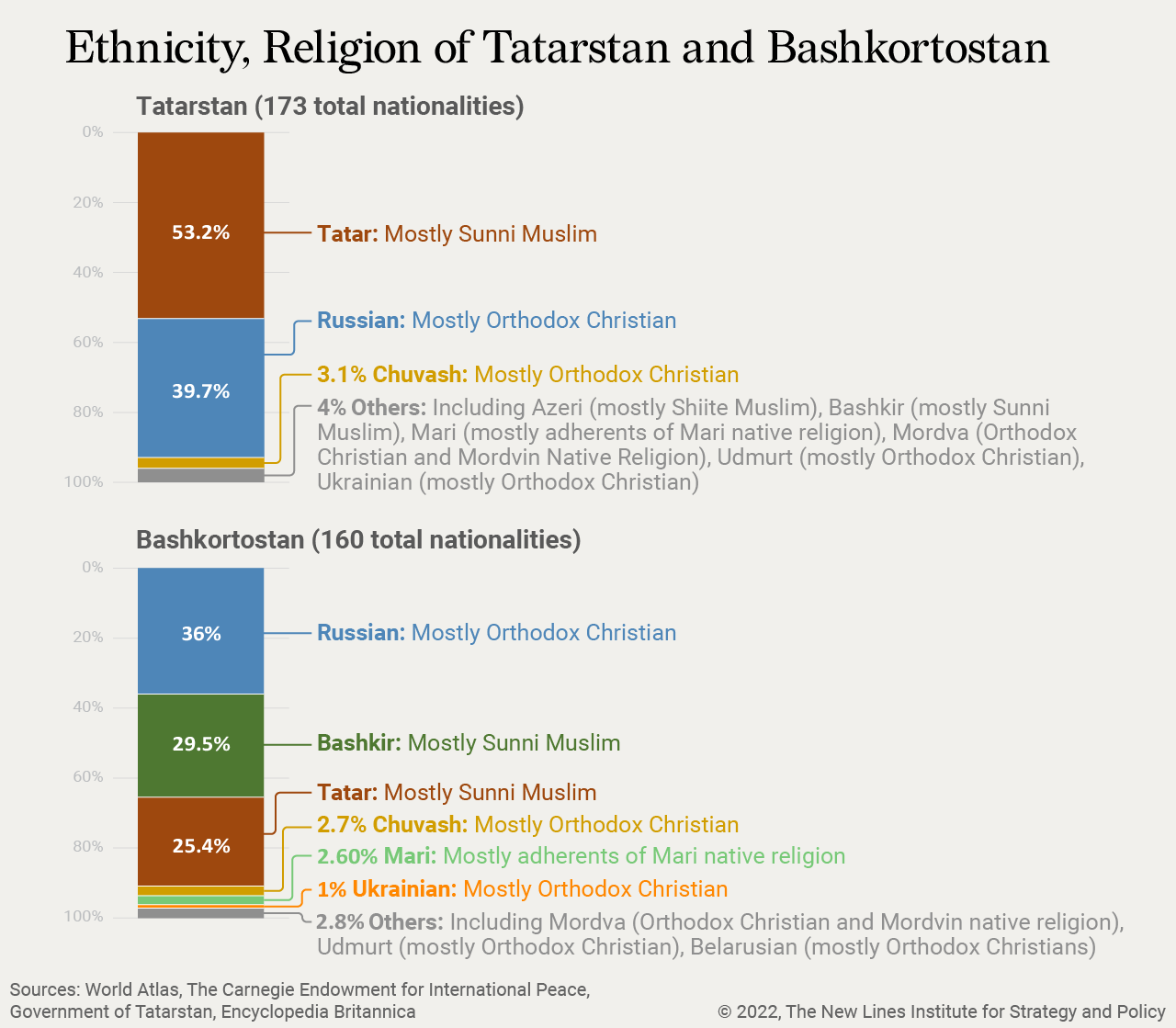

Bashkortostan and Tatarstan are Russia’s Turkic-majority republics, situated in the broader Volga-Ural geographic area of the country. The indigenous peoples of these republics, Bashkirs and Tatars respectively, are usually referred to as the titular groups of their respective home regions, underlining their historic ownership of the territory. According to the 2010 all-Russia census, Bashkirs comprise 29.5 percent of Bashkortostan’s population, with Russians (36 percent) and Tatars (25.4 percent) being the two other largest ethnic communities. In Tatarstan, ethnic Tatars constitute the majority (53.2 percent) of the population, and Russians are the second-largest ethnic group (39.7 percent).

The 1985 introduction of politics of glasnost and perestroika by former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev has spiraled the rise of ethnonationalist sentiments and demands for greater sovereignty across the Soviet Union, including in what was then the Bashkir and Tatar autonomous Soviet socialist republics. The struggle for greater autonomy in the two regions culminated in declarations of state sovereignty by local governments, which were adopted Aug. 30, 1990, in Tatarstan and Oct. 11, 1990, in Bashkortostan. Bashkortostan, alongside other regions of Russia with the exception of Chechnya and Tatarstan, went on to sign a federal agreement with Moscow less than a year later.

Tracing their statehood back to the Kazan Khanate, which was captured by Ivan the Terrible of Russia in 1552, Tatars saw the collapse of the Soviet Union as the opportunity to partition from Moscow’s iron fist once and for all and reverse the course of history in their favor. And so, with the stated aim “to show everybody that sovereignty is the people’s choice,” then-president of Tatarstan Mintimer Shaimiev ordered a referendum on regional sovereignty on March 21, 1992. With 61.4 percent of the population voting in favor of succession, Shaimiev was granted an upper hand in subsequent negotiations in Moscow. Nearly two years later, Tatarstan and Moscow signed a power-sharing treaty that allowed the republic to pass its own laws, collect taxes, and even grant special citizenship status to its residents.

Though the two regions took slightly different routes in their relationship with the Kremlin, their willingness to negotiate greater autonomy from Moscow and the seeming eagerness to defend the rights of their indigenous populations could provide a good base for development of regional democratic practices. Contrary to what might have been expected of them, both Bashkortostan and Tatarstan have embarked on ethnocratic paths.

Shaimiev and his Bashkir counterpart, strongman Murtaza Rakhimov, waged their personal struggle for the consolidation of power. Carefully capitalizing on their positionality within local elite networks and utilizing the agenda advanced by regional nationalist movements to their

political advantage, both were able to quickly secure their hold on regional government structures. Pro-democracy and pro-independence activists such as the All-Tatar Public Center, which was the driving force behind multiple pro-independence protests that took place in Tatarstan in the 1980s and 1990s, were marginalized with the aid of the ruling elites.

The ethnocratic reigns of Rakhimov and Shaimiev have had a profound impact on the workings of regional politics, economy, and social structures. Both Rakhimov and Shaimiev increasingly relied on clan and kinship connections in their regime-building. Shaimiev, for example, gave several key political and economic roles to members of his family and extended clan. Rakhimov went even further and appointed his son Ural as the Chair of the Board of four of the region’s largest companies. He also gave all key governmental positions to members of his extended clan — ethnic Bashkirs hailing from Rakhimov’s native Kugarchinsky District of Bashkortostan. As locals frequently note, to become successful in Bashkortostan’s politics of the 1990s and early 2000s, one had to be of the same circle with local elites, an ethnic Bashkir, and a strong advocate for traditional Bashkir and Islamic values.

On the sub-regional level, Rakhimov’s politics of clannism manifested in an unfair redistribution of funds in favor of Bashkortostan’s regions with Bashkir majority populations, as well as capture of key positions in local institutions by local clans and people connected to them by means of belonging to the titular ethnic group.

The overreliance on clan networks and resulting corruption meant that local regimes came to mirror the Kremlin. That resemblance made it much easier for the federal government to co-opt the local leaders, leaving them defenseless against the Kremlin’s attempts at Russifying the regions and claiming control of their key assets.

In 2010, the Kremlin pushed to replace Shaimiev and Rakhimov — who were often perceived as “old guard” nationalists — with more loyal technocrats. Rakhimov’s eventual departure resulted from his public falling out with the Kremlin and was accompanied by a series of high-profile scandals and a drastic drop in public approval. In July 2010, Rakhimov’s post was assumed by Kremlin loyalist Rustem Khamitov. Subsequently, the entire Rakhimov clan suffered a loss of control over economic and political assets it had held for nearly 20 years. Contrary to how it might seem, Rakhmov’s downfall was not a solely good thing for Bashkortostan, as the republic’s indigenous population also lost a fearless protector of their basic rights such as the enforcement of Bashkir as the official second language. Most importantly, however, Moscow gained control over the key driver of the region’s economy, the energy sector. Bashkortostan’s oil giant Bashneft was first bought out by billionaire Vladimir Yevtushenkov and then taken over by Rosneft boss Igor Sechin.

In Tatarstan, Shaimiev, with the Kremlin’s backing, initiated a peaceful transfer of presidential powers to a handpicked candidate, close ally Rustam Minnikhanov. After Minnikhanov assumed the presidency in March 2010, Shaimiev was awarded the formal title of the State Counselor of Tatarstan, thereby retaining a degree of political influence. The comparatively smooth transition of power, which according to some insider accounts was a result of Shaimiev’s negotiations with

the Kremlin, meant that Tatarstan was able to retain most of its autonomous privileges. Most importantly, the government of Tatarstan retained a controlling stake in oil giant Tatneft and indirect ownership of other major companies, including Europe’s largest petrochemical producer, Nizhnekamskneftekhim.

While Tatarstan’s leadership was able to keep most of the money made in the region within it — a luxury in the modern Russian system where most profits made by wealthy republics are collected by Moscow — it still had to pay a toll to the Kremlin in other ways. In 2017, Putin forced the Tatarstani government to abandon mandatory lessons of Tatar in the republic’s schools in spite of the fact that the region’s constitution equates its status to that of the Russian language. In 2021, when Minnikhanov publicly announced that he will follow the law stripping him of the presidential title despite opposition from some of the highest ranks of Tatarstan’s government, many suspected that he had done so in exchange for a guarantee to keep his post for another term. In 2022, Minnikhanov not only vocally supported Russia’s colonial war in Ukraine but made a number of controversial statements in support of the preservation of ethnic Russian culture and the Russian language. That’s how Tatarstan became “just another region” of Russia, with Minnikhanov as its ordinary head.

(Re)creating the Nation

As Muslim-majority republics, both Tatarstan and Bashkortostan often fall victim to being examined through an orientalist lens. Since the question of decolonization of Russia has entered the mainstream academic discourse, many prominent voices have advocated that “Russia’s stans” are simply incapable of building democratic institutions and sustaining democratic practices.

However, such scholars fail to take note of the specificities of regional Islamic practices — most people in the region adhere to the relatively more flexible Hanafi school of jurisprudence — and, most importantly, of high levels of ethnic diversity of these regions. Tatarstan is home to 173 ethnic groups, including those who have lived on the territories of the republic for many centuries. Chuvashs, for example, the third-largest ethnic group in Tatarstan, began to settle in the republic in the 1500s. Most Tatarstani Chuvashs are speakers of three languages, including their native Chuvash, Russian and Tatar. Bashkortostan is home to representatives of more than 100 ethnic groups. Across the republic can be found the lands that were historically settled by, for example, Maries, Chuvashs, Volga Germans, Ukrainians, and Poles.

The historically high levels of ethnic and, relatedly, religious diversity mean that the sense of “belonging” to these regions doesn’t depend solely on one’s ethnic identity or religious affiliation. Both Bashkortostan and Tatarstan have long possessed all prerequisites for developing and fostering the sense of what local pro-democracy activists label as “political nationalism” that centers around the attachment to an ethnically diverse political entity, the common motherland rather than one ethnic group.

In 1992 that idea was voiced by prominent Tatar activist Marat Mulyukov. ″Nobody is going to expel them. They are ‘our’ Russians; we have lived together for several hundred years,″ Mulyukov told an AP journalist when asked whether ethnic Russians would be expelled from independent Tatarstan.

Thirty years later, Mulyukov’s sentiment was echoed by Ruslan Gabbasov, the exiled head of the leading regional opposition group, the Bashkir National Political Center (BNPC). “Our project is one of a political nation like in Ukraine, where a Jewish president is leading the state and ethnic Georgians, Chechens, Crimean Tatars are fighting alongside [ethnic] Ukrainians and all equally consider Ukraine their motherland,” Gabbasov said in an interview with the author in May this year.

As if fighting with a ghost of ethnocracy of Murtaza Rakhimov’s era, Gabbasov’s political platform carefully addresses why a representative of each nationality living in the republic is equally important and what it means to be “a member of a Bashkir political nation.” BNPC’s predecessor organization, Bashkort, was the North Star of the Bashkir civil society space, which has often been perceived as “dormant” by area specialists. Bashkort was a leading force behind the 2020 mass protests in defense of the sacred Bashkir mountain Kushtau, which was threatened to be destroyed by the Bashkir Soda Company that planned to use the area for limestone mining.

According to Gabbasov himself, Bashkort’s support levels in the republic were so high that it could easily win in local elections despite the potential forgery attempts usually made by pro-Kremlin forces. Likely sensing the danger, in 2020 authorities dubbed the organization as “extremist” and outlawed it. Gabbasov’s key ally Ayrat Dilmukhametov was arrested and sentenced to nine and a half years in a maximum-security prison. Other activists linked to Bashkort or the 2020 protest movement have also suffered varying levels of government repression. Gabbasov was forced to flee the country under threat of arrest earlier this year and, while in exile, founded BNPC.

BNPC’s carefully developed political platform and high levels of support at home point to continuing public demand for greater independence from the Kremlin in political decision making. Its existence also proves that despite the mounting repressions and Kremlin-administered control over the region, Bashkortostan has a new generation of democratically minded and motivated political leaders who are ready to seize the opportunity when their time comes.

For Tatarstan, the future is more uncertain as its pro-democracy forces consist mainly of the same opposition leaders of the 1980s and 1990s, though the national scene and the Tatar diaspora is still full of young activists who have a potential assume a more active role in building the republic’s future if the times call for that.

Recommendations

While the possible downfall of the Putin regime might still be a while away, it is time for the West to invest in democratic futures of Russia’s regions — particularly the “ethnic” republics — to help them avoid repeating the vicious circle of democratic backsliding and ethnocratization. U.S. policymakers should shift the lens through which they view Russia and work toward building channels for diplomatic negotiations and economic partnerships, as well as focusing its soft power projection efforts on the regions and not just the Kremlin. As Washington-Moscow relations worsen, it is more important than ever to recognize that a greater diversity of potential partnerships exists in Russia and to open new paths with other power centers across the vast country. In doing so, the U.S. and its allies may build from the Turkish model, which has seen considerable success.

At the same time, the U.S., while continuing to impose sanctions on the Kremlin over the invasion of Ukraine, should look to proactively sanction acting policymakers and other actors beyond the Kremlin inner circle that are linked to violations of rights of Russia’s minorities. This includes, for example, sanctioning individuals involved in orchestrating mass arrests and repressions against the participants of the 2020 Kushtau protests in Bashkortostan.

Beyond the already known instances of repression, it is important for Western policymakers to continuously monitor for new instances of ideological and economic attacks on local activists. In cases of Russia’s Muslim-majority regions, such attacks are likely to manifest in increased “counter-terrorism operations” at the local level and mass arrests of activists on terrorism-linked charges.

As many local indigenous activists were forced into exile and now continue their work outside of Russia, the U.S. should look to establish links with related diaspora communities and bolster their capacity through civic education and logistical support. It currently is particularly important to support the many indigenous initiatives working to undermine the Kremlin’s offensive in Ukraine, particularly by providing legal and financial support to conscientious objectors and disseminating truthful information about the ongoing war to their native communities in Russia.

Leyla Latypova is a reporter for The Moscow Times. Prior to joining the publication, she worked as a geopolitical risk analyst covering Russia, Eastern Europe, Central Asia, and the Middle East. Latypova is also pursuing a postgraduate degree at the University College London, School of Slavonic and Eastern European studies, where her research focus is on regional politics and mobilization in Russia. She tweets at @latypovaleyla.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of the New Lines Institute.