Listen to Article

Parliamentary elections in Lebanon on May 15 will keep in power many of the same political elites that have led the country into a ruinous economic crisis, a dispiriting outcome for the domestic opposition and foreign actors aiming to avoid the creation of yet another failed state in the region. These results should impel stakeholders to navigate the narrow limits of change imposed by domestic and regional conditions.

Parliamentary elections, and ways to deter the ruling elite from cancelling the polls, have taken center stage in debates about Lebanon in the past year. Voting in a new parliament might have been an inflection point toward the change needed to unlock substantial foreign assistance and thereby arrest the country’s descent into ever-deeper crisis. But projections suggest that they will only bring very moderate change.

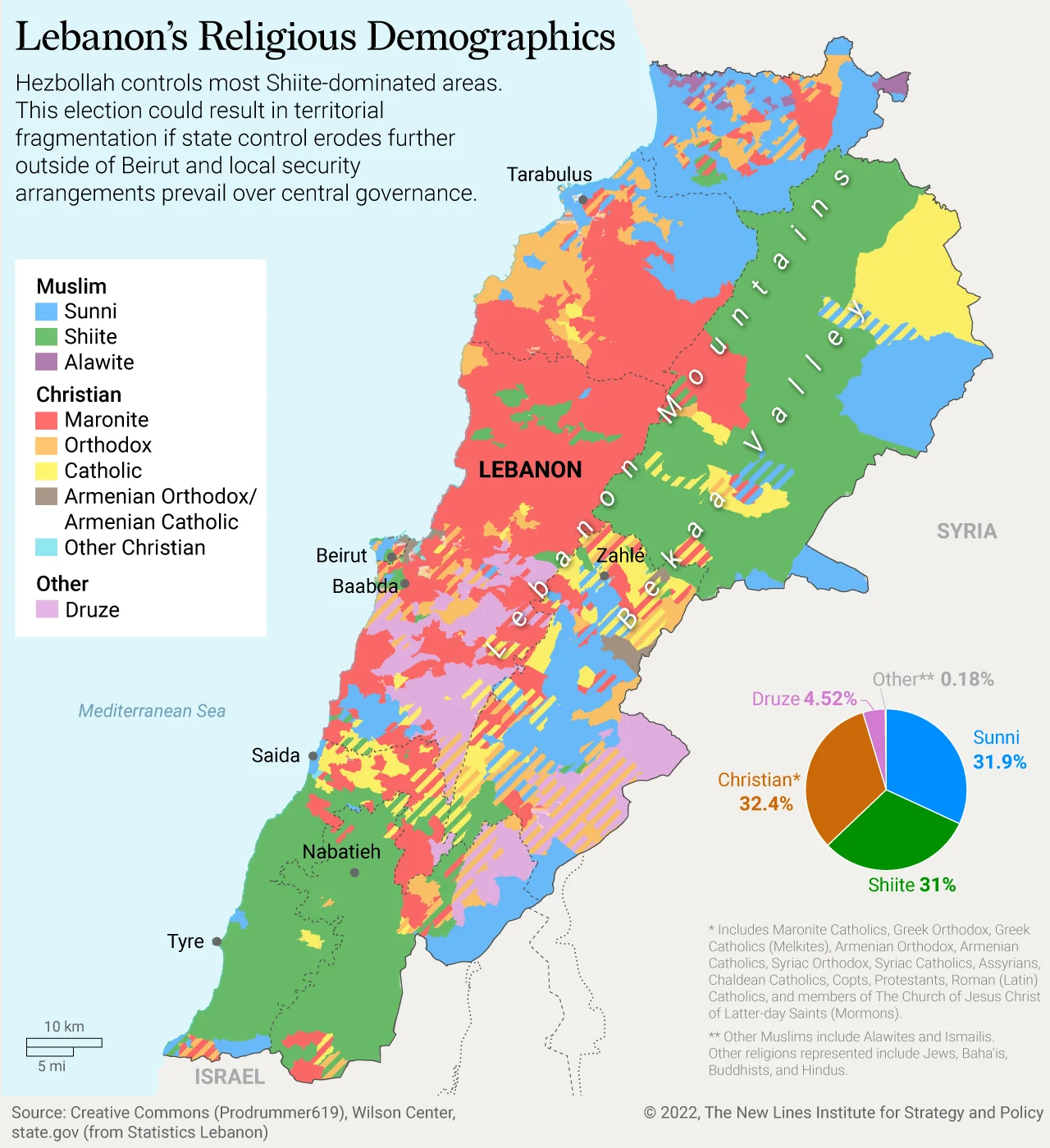

The Shiite parties Hezbollah and Amal are expected to retain their share of MPs, while their Christian ally Free Patriotic Movement (FPM) is expected to lose. On the other hand, the election boycott of the main Sunni political player, former Prime Minister Saad Hariri, may allow a larger number of Sunni candidates leaning toward Hezbollah to succeed than in the last elections. Whether such an increased number of pro-Hezbollah Sunni MPs can offset the losses of the FPM will decide if the Hezbollah/Amal/FPM alliance can retain its majority. Hariri’s withdrawal will, in turn, deprive the anti-Hezbollah camp of one of its main pillars and leave it fragmented. Contenders who claim to represent the demands of the 2019 protest movement may win some seats, distributed between figures with a proven record in activism, defectors from traditional parties, and traditional parties rebranding themselves as opposition.

That the Lebanese would mostly reelect the political class that failed them so badly does not come as a surprise. Sectarian polarization, the growing dependency of an increasingly impoverished population on the clientelist networks maintained by the traditional parties, and the lack of opportunities – in particular, funding – for the opposition movements, in addition to their inability to form tactical alliances, are all significant factors that help explain this choice. Most importantly, however, these movements failed to convince would-be voters that they have a credible plan for change. That is nothing they should be blamed for; rather, the expectation that the current crisis could generate real change was misplaced from the outset. To understand the narrow limits that those trying to save Lebanon from disaster need to navigate, it makes sense to look at how the foundations of the current political order were laid thirty years ago, when the country emerged from its 15-years long civil war. Then, as now, it is a narrative of a new beginning that turned out to be chimera.

State-Building as Make-Believe

Looking at the way in which the current political order was established 33 years ago may serve to avoid errors that helped create and prolong the current crisis: taking at face value the rhetoric of actors who pretended to rebuild the Lebanese state, while their real objective was to control, capture, and plunder state institutions.

The 1989 Taif Accord, agreed toward the end of the Lebanese Civil War, did not actually inaugurate a process of “national reconciliation” as the official name of the document suggests. Rather, the leaders running the war at the time were forced to change their business model, and those who read the signs of the time did spectacularly well, while those who failed to comply with the new rules ended up in exile or jail.

The business model of the 1975-90 civil war had been based on material and political support from external players using Lebanon as a theatre to contest the regional balance of power. Domestic players used this support to control territory by force of arms, extorting the population and bending institutions to their will. When the Cold War ended in the late 1980s and the Persian Gulf War appeared to augur an era of unchallenged U.S. hegemony, Lebanon’s role as the ersatz battlefield for the Middle East ended.

Resources would now flow to the state and the private sector. Accordingly, the warlords traded control over arms and territory for control over the state. They inserted militia men and party soldiers into institutions, and converted wartime loyalties into votes that turned warlords into elected leaders. Control over institutions then allowed the newly minted statesmen to control resource streams and establish themselves in the economy, where they cooperated with billionaire businessmen who in turn leveraged their financial heft to gain a foothold in politics.

Under the watchful eyes of the Syrian overlords who skimmed off their share of the proceeds, business owners and politicians created a feedback loop converting control over institutions into consistent support at the polls. Like every racket, this system of competitive state capture was prone to scuffles over share and turf and violent suppression of discontent. Yet the arrangement paid off so handsomely that it lasted for nearly 30 years. So rewarding were the spoils of the Taif truce that it survived the collapse of the Middle East Peace Process; the 2005 withdrawal of Syria, which served as its original enforcer; the war between Hezbollah and Israel in 2006; a three-day mini-civil war in May 2008; and the first phase of the civil war in Syria.

The Curse of Easy Money

Despite these upheavals, the money kept flowing into Lebanon as foreign actors like the EU and the U.S. sought to maintain some stability in a troubled region and as Gulf countries continued to throw good money after bad to keep their allies afloat and the country in their orbit. Lebanon was approaching bankruptcy around the turn of the millennium, before the Paris I and II donor conferences arrested the rapid growth of the public debt under the pretext of institution building. By 2006, indicators were heading south again. Paradoxically, though, the destruction wreaked by the war between Hezbollah and Israel triggered yet another surge of donations, peaking in the 2007 Paris III conference. In 2008, the global financial crisis prompted many investors to move capital to the make-believe safety of the Lebanese banks. With the beginning of the refugee influx from Syria in 2012, humanitarian aid added yet another stream to the permanent inflow of foreign currency that the Lebanese economy had become hopelessly dependent on. Remittances sent home by those who had moved to greener pastures continued throughout.

Yet all the easy money could never be enough. Already in 2015, the IMF discovered a $4.7 billion hole in the Central Bank’s balance sheets. As the influx of external investment started to dry up, the Lebanese Central Bank resorted to breakneck financial acrobatics by offering implausibly high interest rates and offering irresistible conditions to local banks that would hand over U.S. dollars that Lebanese depositors had entrusted them with, in the misguided belief that keeping their savings in foreign currency would protect them from crashes of the Lebanese lira like they had occurred during and after the civil war.

The charade continued nevertheless. As late as April 2018, French president Emmanuel Macron convened yet another donor conference in Paris, this time called the “Conférence Économique pour le Développement, par les Réformes et Avec les Entreprises,” or CEDRE, in a nod to Lebanon’s iconic and biblical national tree. Perhaps not entirely by accident, CEDRE occurred exactly one month before Lebanon’s 2018 parliamentary elections, supposedly boosting the fortunes of then-Prime Minister Saad Hariri, with the promise of up to $11 billion in soft loans and foreign investment – nearly as much as Paris I-III combined. Hariri still got a drubbing at the polls, though he still was reappointed, and no progress was achieved toward meeting the reform conditions tied to the package.

That was no coincidence: Politics in Lebanon since the early 1990s have been reduced to crude competition that has resulted in the political elite either failing or refusing to engage in policies beyond maximizing the resources they can appropriate for themselves and their clients.

The problem goes deeper than graft and malign neglect. In early 2019, the established parties could have sat together and agreed on a minimum of piecemeal reforms to once again attract benefactors and investors. While such an agreement would not have resolved a deeper crisis, it may have enabled assistance and attracted other dollars and bought more time. Instead, each party dug in and focused on shunting the political and material cost upon its political rivals and the population. Three years and $70 billion lost later, the situation remains the same, with aid to Lebanon stymied as its leaders continue to prioritize short-term, narrow interests.

Post-Election Prospects

There has been little public discussion thus far on what will happen after the polls. With the opening session of the new parliament, the current government headed by Najib Mikati will be reduced to a caretaker status with very limited authority – certainly not enough to enact or implement the reform and regulatory work required to obtain an $3 billion IMF rescue package. Some observers and foreign actors still seem to hope that, faced with the prospect of immediate collapse, the traditional players would refrain from leveraging election results to push for marginal changes in the balance of power and would simply agree to reappoint an only slightly modified version of the current government, again under the leadership of Mikati, to move forward on the arduous path to reform.

Even if that scenario came to pass, the sheer magnitude of the reforms required by the IMF in its April 7 Staff-Level Agreement – including a restructuring of the financial sector and fixing the monetary system, fiscal reform, a reform of public enterprises, and uprooting corruption – would seem to rule out quick progress toward a deal. The far more likely scenario is that all major players will fight for power. To a significant extent, the formation of the current government under Mikati in September 2021 succeeded because it was clear that it would have a life span of little more than six months. Any government confirmed after May 15, by contrast, could serve a full term and would have to take measures that touch upon powerful entrenched interests, starting with the close connections that many politicians have with the financial sector. Compared to six months ago, the stakes are far higher.

Government formation will be even more complicated because by Oct. 31 the term of President Michel Aoun will expire. Lebanese presidents are elected by parliament and require the support or a least acquiescence of a two-thirds majority of sitting MPs. No political camp can muster that alone. (Aoun himself is believed to be seeking to pass the presidency to his son-in-law, FPM chairman Gibran Basil.) Failing a larger compromise, Lebanon is likely to be without either a government or a president in October.

According to the constitution, any vacancy in the presidency means that the presidential authorities are delegated to the Council of Ministers, making the government the sole organ of executive power – a prospect raising the stakes involved in government formation even more. Furthermore, it is unclear whether a caretaker government, which according to the constitution wields only narrowly circumscribed prerogatives, could receive such a delegation of presidential powers. In such a situation, the end of Aoun’s term may create a constitutional vacuum. No reforms will be possible amid such a stalemate or prolonged stand-off over government formation.

Disintegration

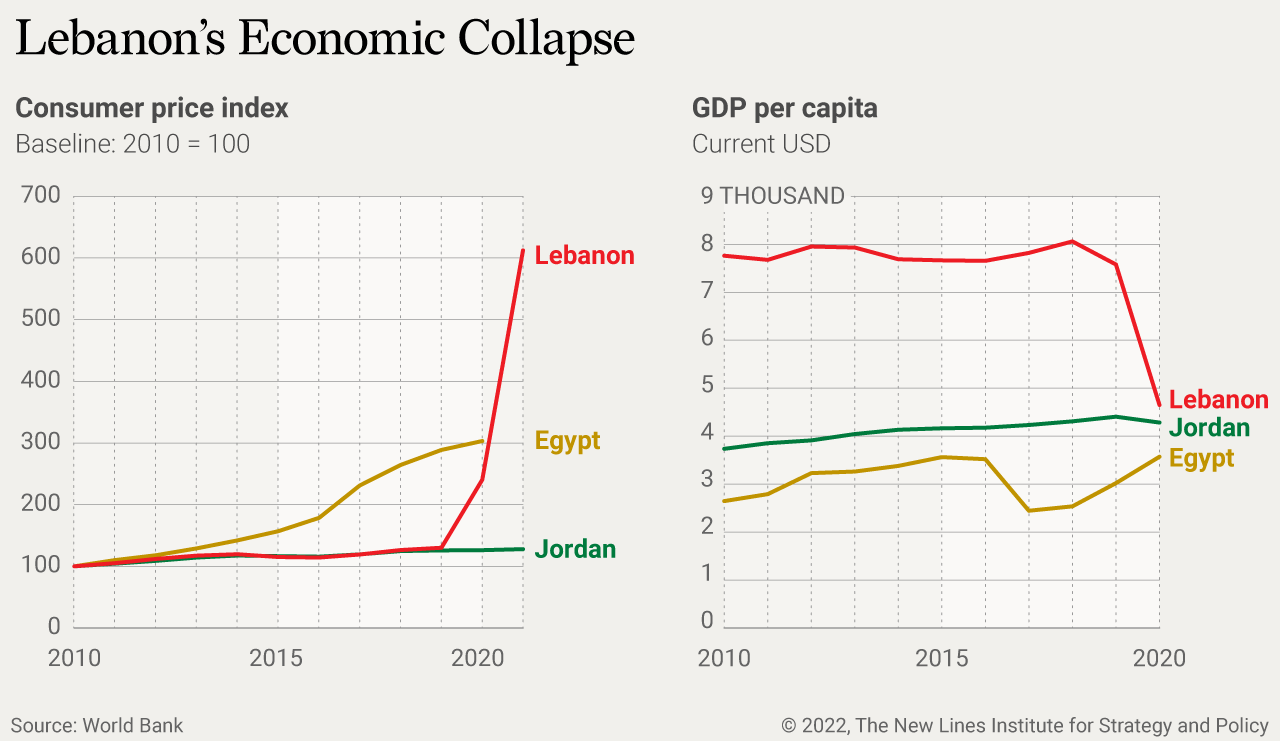

As politicians tussle, living conditions will continue to deteriorate and state institutions will disintegrate. Since mid-January, when the exchange rate of the Lebanese lira to the U.S. dollar crossed the 30,000 mark – from a pre-crisis value of around 1,500 – the Lebanese Central Bank has propped up the currency by injecting dollars into the market – at a price of an estimated $500 million per month. Economic experts concur that, with foreign exchange reserves now below $10 billion, the policy is unsustainable and it is only a matter of time before a new round of hyperinflation begins.

Lebanese without access to U.S. dollars will get even poorer, with a real threat of famine looming, along with the potential for a complete collapse of even the most basic public services as winter approaches. Perhaps the most worrisome aspect is the erosion of the security sector. Charged with an ever-expanding mandate that includes policing protests and controlling sectarian clashes, the army is woefully overstretched. Security forces rely on charity to keep their equipment running. Police minimize patrolling since there is no money to fix vehicles that break down, and superiors look the other way as junior ranks take on second jobs to make ends meet, fearing a wave of desertions.

At the periphery, local forces are already filling the security void. Volunteers operating under the auspices of municipalities have appeared in response to a surge in crime since the beginning of the crisis. These forces could easily become professionalized, with financial support from local businesses for their upkeep turning into permanent taxes and soldiers and police in need of additional income putting their training and government-issued arms to more gainful use.

This could result in a mosaic of local security arrangements, determined by the availability of resources, the social and sectarian composition of areas, and the presence of organized groups capable to enforce control. In some places, this may blur into a rule of armed rackets; in others, political parties could seize the opportunity to monetize their organizational capacity and assert presence on the ground. Where areas of control overlap or where security threats are seen as emerging from adjacent neighborhoods, turf wars will ensue. And where no one is really in control, security voids will open that may be filled by criminal or extremist groups. Meanwhile, the state will focus what remains of its security capacity on vital areas like the capital and critical infrastructure like major roads, the airport, and powerlines.

Breaking the Cycle

Perhaps the most important lesson of the failed state-building project of the 1990s is that neither Lebanese nor foreign actors should let themselves be fooled by narratives of comprehensive change. Just like ending the civil war in 1990 did not put an end to the power of militia leaders, reform initiatives will not wipe out the established political elite. After the elections, they will remain unavoidable interlocutors for any attempts to arrest the country’s decline, and they will use this position to make sure that their core interests are secured in the process. For all the rhetoric of accountability and good governance, foreign actors will likewise have no choice but work with the powers that be. They should do their utmost, as most have been trying already over the past three years, to prod the established political parties to finally put the greater good over their own narrow interests.

The challenge will be to gradually expand the areas of governance and attached resource streams that such players do not control. This will require a persistent, hands-on involvement of foreign institutions and countries to make sure domestic actors play by the rules, and of domestic actors pushing to establish new rules. The IMF can perhaps stop the government and the Central Bank from cooking the books, but it won’t deliver the policies needed to rebuild the economy, fix the health sector, or create a sustainable energy mix. For this, Lebanon will need a strong, professional civil society and a private sector that succeeds without political protection. The high level of competence in both sectors, and the expected (if limited) entry of new political forces hailing from this environment through the current elections, suggest a significant potential. But they need to be in there for the long haul, alongside those who have been pushing for change since 2019 and before, pressing for policies that generate public good and fighting the rackets that divide them up, wresting turf from the established parties.

Finally, as long as Lebanon remains a theater for competition between Iran on the one hand and Israel, its newly minted Arab allies, and an increasingly reluctant U.S. on the other, it may not have room for pragmatic domestic compromises. Rather, the political camps aligned with these opposing regional trends will remain locked into their confrontation over where Lebanon should be positioned in that much larger ideological struggle. Solving the current crisis may require a basic understanding between regional actors. The U.S., Arab states, and Iran need to realize that yet another failed state in the region is liable to create stability risks that will come back to haunt them. Only once Lebanon has been insulated from regional competition may domestic players revisit their political calculations and consider offramps that require compromise.

Heiko Wimmen oversees Crisis Group’s Iraq/Syria/Lebanon project. Prior to joining Crisis Group, he was an associate researcher at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs in Berlin. He has also published with the Carnegie Middle East Center and MERIP, and recently oversaw an edited academic volume on Elite Change and New Social Mobilization in the Arab World.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of the New Lines Institute.