Over the past two decades, Poland has become one of the most important countries in Eastern Europe, helping to form NATO and the EU’s policies toward Ukraine and other former Soviet republics after it recovered from occupations by both Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. With serious attention being paid to the danger of Russian aggression on NATO’s eastern flank, it is more important than ever to understand how Poland’s unique historical experiences, its geopolitical position, and its traditions of geopolitical thinking make it an important strategic ally for the U.S.

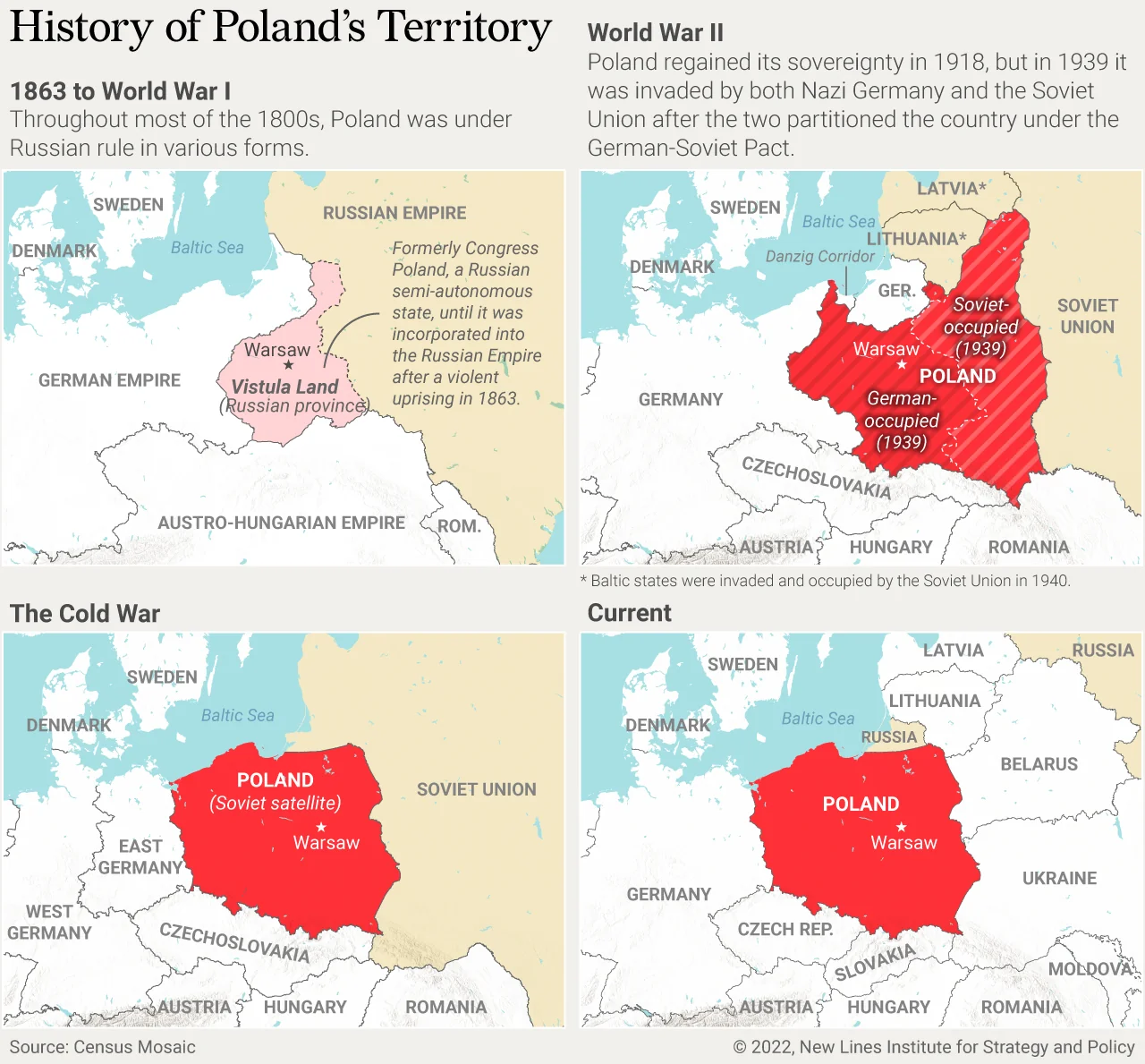

In 1795, Poland was wiped off the map of Europe by the partition of three surrounding empires. It returned as an independent state in 1918, but 21 years later, it was invaded and occupied by the Nazis. In 1945, it reappeared as a Soviet satellite and a nation devastated by the twin horrors of Nazism and Stalinism. Only in 1989 did it reemerge as a truly independent sovereign state, and it has taken it some years to assert itself on the global stage. The prominent memory of all these events is essential to understanding Polish political and geopolitical thinking today.

The dramatically changed political situation in eastern Europe caused by Russia’s renewed imperialism since the early 2010s has in Poland’s eyes vindicated its longstanding fear and anxiety over Russia. For example, before Russia’s Feb. 24 invasion of Ukraine, Poland had been planning to increase defense spending from the 2% of its GDP required by NATO to 2.5%. But in mid-March, both chambers of the country’s normally highly polarized parliament unanimously passed a “Homeland Defense Bill” that boosts defense spending to 3% of GDP.

At the eastern border of the institutional West, Poland has always felt securing Eastern Europe from Russian aggression was a pressing, existential matter. Its major allies have not usually shared its concerns. In past eras, the geopolitical problems that led Poland to catastrophe shaped distinctive Polish visions of Eastern European political order and what Poland must do to secure its place in it. The successes of Polish foreign policy since 1989 have given the country a newfound importance in the region, thanks to its powerful alliances, and it now has a chance to influence the course of European history for the first time in centuries.

The Lost Commonwealth

The “original” Polish state that existed until the end of the 18th century was the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. It was formed by a union between the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, both of which had existed since the early Middle Ages, and both of which extended far beyond the modern borders of Poland and Lithuania. The Commonwealth initially encompassed all of today’s Belarus and most of today’s Ukraine, meaning that for most of Europe’s pre-modern history, Ukraine and Belarus were associated with Poland, not Russia.

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was for a long time one of the most powerful states in Europe. It was unique in Europe for its unusually large nobility – the szlachta – as well as for the fact that it was an elective monarchy in which the monarch was relatively powerless. This had its limitations, but the country’s true curse was its geography; it had no defensible frontiers and was surrounded by rising powers. Two of these powers would decide the course of Poland’s history for centuries.

Along Poland’s western border, the Kingdom of Prussia became a major military power before later acting as the core of a united Germany. And on its eastern border, the Russian empire emerged from its Muscovite nucleus to become a Eurasian superpower. Russia slowly chipped away at Polish territory, developing an imperial ideology of “reuniting the lands of Rus” in the process to justify the need to conquer what are now Belarus and Ukraine, an idea Russian President Vladimir Putin has consciously evoked to justify his aggression in Ukraine.

By the late 18th century, the Commonwealth was weakened to the point that it could not resist its partition by Prussia, Russia, and Austria. One final attempt was made by the Polish statesman and hero of the American Revolutionary War Tadeusz Kościuszko to save the country in 1794 through an armed uprising, but after being defeated in the field by the Russian Army, he is apocryphally quoted as having said, “Finis Poloniae” – “The end of Poland.”

The loss of Polish statehood and the accompanying suppression of Polish culture has left a deep imprint on Polish politics. Poles fought several doomed insurrections in the 19th century, taking up the idea of Poland as a “Christ of Europe” for their messianic national suffering.

The collapse of all three empires that had partitioned Poland in 1795 due World War I paved the way for Poland to carve a state out of the chaotic postwar settlement. Its eastern border was not set, however, and it took defeating the Soviet Union in the Polish-Soviet War to secure independence. What Poland failed to achieve was what its leader and “father of the nation” Józef Piłsudski wanted: a revival of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Intermarium and Prometheism

Piłsudski recognized that a Poland limited in its statehood and alliances to only Poland was vulnerable to the same partition between Moscow and Berlin that had erased it from the map in the first place. His two-fold solution would define Polish geopolitical thinking in the interwar years.

First, he wanted to strengthen Poland’s geopolitical position by creating an “Intermarium” federation of the small and weak Central European states that were stuck between Germany and Russia. This was not so much a concrete plan as a vague concept, and one that was never really pursued in earnest. Second, he wanted to weaken the position of the country’s principal potential adversary, the Soviet Union. This would be done by supporting the independence movements of non-Russian subject peoples and dismembering the Russian empire in its Soviet form, a policy known as “Prometheism.” Piłsudski’s vague plans not only failed but backfired, as Polish relations with neighboring peoples soured after his government’s Polonizing policies toward national minorities and Polish annexation of Vilnius, which was claimed by Lithuania.

In the end, Poland was subject to another de facto partition between Nazi Germany and Stalin’s Soviet Union in 1939. Poland lost nearly 20% of its population in World War II – a higher percentage than any other sovereign state. Almost its entire Jewish population was murdered by the Nazis, much of its political and military elite were executed by the Soviets, and over a million Poles were slaughtered by both.

Poland’s borders were moved several hundred kilometers westward after the war, completely changing the physical and demographic geography of the broken country. For the next 45 years, Poland was a Soviet satellite state with no independent foreign policy of its own. This experience of partition, mass slaughter, and relegation to semi-sovereign status during the Cold War is once again crucial to understanding modern Polish thinking.

Poland’s collective memory – institutionalized in the Institute of National Remembrance – is one of national suffering, loss of sovereignty, and suppression of independent cultural life. It reinforced an aggressively hawkish stance toward a Russia that remains the one major threat to the country, as well as a widely popular desire for American friendship and protection.

From Warsaw Pact to Euro-Atlantic Integration

In 1989, the communists were voted out of power after the Solidarity movement pressured them into holding free elections, and by 1993 the Red Army had left the country completely. Poland was once again an independent country. Its next aim was to stay that way.

The country’s overarching foreign policy goal for well over a decade after 1989 was “Euro-Atlantic integration” – that is, joining the European Union and NATO. This goal was borne out of security concerns and a strong cultural and economic impetus for Poland to symbolically “return to Europe” after decades of Soviet subjugation.

Like in the interwar years, Poland’s internal policy of strengthening its position relative to potential foes through NATO and EU membership was complemented by an external policy to ensure that the “Prometheist” collapse of the Soviet Union would not be reversed. In 1991, the USSR had dissolved into 15 sovereign republics, splitting apart the Soviet empire in Eastern Europe as well as the Soviet Union itself. Ukraine and Belarus, neither of which had ever been established sovereign states, both appeared on Poland’s eastern border overnight, acting as a buffer between it and Russia.

It became official Polish policy to be friendly to or, if possible, allies with these countries. This was known as the Giedroyć doctrine, named after Jerzy Giedroyć, a Polish writer and political activist who was the editor of the Paris-based Polish periodical Kultura during the Cold War. Giedroyć was one of the most important Polish intellectuals of the 20th century, largely because he operated completely outside of the country, and was able to develop his own political and cultural ideas free from the censorship of the Polish People’s Republic.

One of Giedroyć’s innovative ideas (for the 1950s) was that Poland should accept its post-WWII eastern boundary, giving up its claims on Lviv and Vilnius and instead seeking reconciliation with its eastern neighbors. He also rejected the idea that Russia should be treated any more importantly than any other country in the region, as well as the notion that Eastern Europe should be a space for Russian-Polish imperial competition. His ideas have largely shaped Poland’s “eastern strategy” ever since 1989.

Poland’s history with its neighbors has often tended more toward conflict than reconciliation. In traditional Ukrainian and Soviet historiography, Polish-Lithuanian rule over Ukraine is condemned as a time when the Polish nobility oppressed the Ukrainian peasantry and its culture. Meanwhile, in Poland, Ukrainian nationalism was long associated with the brutal massacres of Poles by ultranationalist militias in today’s western Ukraine during WWII. Even Poland and Lithuania, now close allies, had strained relations in the 20th century due to rival claims over Vilnius and Poland’s taking it by force in the aftermath of WWI.

But in the 1990s, the Polish government prioritized regional reconciliation over pursuing territorial revisions, leading to its joining NATO in 1999 and the European Union in 2004. By the mid-2000s, Poland’s strategic, economic, and cultural goal of Euro-Atlantic integration was essentially complete.

Under the Wing of the Hegemon

The idea that “demographics is destiny” is simplistic but can be a useful tool to illustrate certain dynamics. In 1989, the population of the Soviet Union was 286 million, while the total population of all its satellites in Eastern Europe just 113 million. The far larger and more powerful Soviet Union easily dominated small Eastern European countries.

Today, Poland has a population of about 38 million while Russia’s is about 145 million. But Poland allied with Ukraine, Belarus, and the Baltic states would add up to nearly 100 million. And that would most likely be within a larger Euro-Atlantic security umbrella. In size, distance, and relative power of alliances, Poland would face little threat from Russia. However, a triune Russian state including Ukraine and Belarus would dwarf Poland and the Baltic states.

Poland’s geopolitical problem is simple: It is a medium-sized country historically threatened on both sides by large superpowers. Nowadays Germany is an ally, but a largely demilitarized one, while Russia continues to be the principal threat. It has always been too small and weak to face Russia directly, so it needs alternative ways to manage the threat.

Euro-Atlantic integration has obviously been a massive step toward that end, but there is always a latent question over whether all NATO allies would honor their commitments to defend their eastern allies. The top Russian foreign policy expert Sergey Karagon, for example, recently called Article 5 “worthless.” Within NATO, Poland has long tried to refocus the alliance on Eastern Europe, even perhaps resenting the focus of its allies on Afghanistan or the Middle East, which it felt were not a direct threat to the territorial integrity of any member states, as opposed to Russia, which threatens not just Poland but the Baltic States, too.

Poland sent over 40,000 troops to fight alongside the U.S. in Iraq and Afghanistan with the hope that it would show that it was a strong and committed ally. However, it did not participate in the NATO intervention in Libya. This illustrates how Poland views NATO as largely an alliance with the United States, and not an exclusive one. Poland has in recent years sought cooperation with the U.S. outside the bounds of NATO, an example being the failed “Fort Trump” proposal to establish a U.S. military base on Polish soil. Poland’s security relies almost entirely on the United States and the deterrence its military power represents.

However, Poland has been bolstering its military in response to Russian aggression since 2014 to act as an independent deterrent. With purchases of equipment ranging from Turkish drones to advanced U.S. tanks, it is ensuring it has the technological capabilities to face Russia head on. As the doubling of its military to 300,000 troops and the production of a domestic air defense system show as well, Poland has the desire and willingness to make itself a military power in Eastern Europe.

A New Eastern Policy

Poland had little impact on international affairs from 1989 to 2004. This is both because it was recovering from the economic damage of the communist period and because it was preoccupied with Euro-Atlantic integration rather than eastern outreach. In 2004, that changed decisively after Ukraine was rocked by a wave of protests in reaction to a rigged election that would have seen the pro-Russian Viktor Yanukovych becoming president over the pro-western Viktor Yushchenko. The protests culminated in the re-running of the election and Yushchenko’s eventual victory.

While Russia disliked what was happening, the entire Polish political spectrum was united in its support for what became known as the Orange Revolution. It was perhaps the first major instance of Poland shaping Western policy toward Ukraine. The Polish government helped mediate roundtable talks between the government and the opposition that helped bring Yushchenko to power, marking this new role as a mediator between the EU and Ukraine. The EU as a whole was then hesitant to act on post-Soviet soil, worrying it would damage relations with Russia, but Poland had no such qualms.

In 2008, the Polish government initiated the EU’s Eastern Partnership, a forum for cooperation between the EU and post-Soviet countries. The aim was implicitly to help prepare countries like Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia for eventual EU membership, something that Poland thought the EU was dragging its feet on or altogether uninterested in. But for Poland, this was a matter of vital national security. When Russia invaded Georgia that same year, Polish President Lech Kaczynski made a trip to Tbilisi alongside the leaders of Ukraine and the Baltic states while the war still raged.

At Tbilisi’s main square, Kaczynski gave a speech now famous in Poland in which he warned: “Today Georgia, tomorrow Ukraine, the day after tomorrow, the Baltic States, and later, perhaps, time will come for my country, Poland.” This illustrates how Poland’s deep historical memory has framed the threat of Russian imperialism as something that must eventually threaten Poland’s vital interests, even if its territory is not immediately threatened.

When Ukraine was rocked by another, even more significant revolution in the so-called Euromaidan, Poland once again took an “unprecedented leadership role” in the EU’s response.

Before 2014, Poland and Ukraine had little interaction beyond Polish support for Ukrainian accession to NATO and the EU. The once-sizable Ukrainian minority in Poland was gone after 1945, and the two countries had no relations during the Cold War. Since 2014, that has changed dramatically. Millions of Ukrainians have gone to work and study in Poland, and Poland is now the most warmly viewed country in Ukraine. Similarly, when Belarus was rocked by protests in 2020 due to the rigged election that kept President Aleksandr Lukashenko in power, Poland went all in on supporting the opposition. It hosts much of Belarus’ parallel pro-Western government and civil society.

At the intersection of the Giedroyć doctrine and Poland’s interwar idea of an Intermarium federation, Poland has pursued a number of different multilateral formats in Central and Eastern Europe. One is the Visegrad Group, a forum of Poland, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, and Hungary formed in 1991 to promote regional cooperation and accession to Western institutions. Another is the Three Seas Initiative, a forum for cooperation between Central and Eastern European EU member states. With Ukraine, Poland has two such forums: the Lublin Triangle comprising Lithuania, Poland, and Ukraine, and the recently formed U.K.-Ukraine-Poland alliance.

The Long Road Ahead

Poland is every NATO and EU country’s most important ally in eastern Europe. But it is an ally with its own history, its own interests, and its own view of the world. While it was passive regarding issues that did not directly affect it, Poland has taken a much more active role to counter the threat of Russian aggression in Eastern Europe. In addition to increasing its own defense spending, Poland has played a key role in providing humanitarian aid and passage to Ukrainians fleeing the Russian invasion, as well as an entire supply network for military aid into Ukraine.

Going into the mid-2020s, Poland’s importance to the EU and NATO will only increase. A Russian success in Ukraine would put the Baltic States and Poland on the highest alert, fearing they might be next. Many in Europe and the U.S. see this as alarmist, but given Poland’s history, it is not hard to see why the country is concerned. Poles see in Ukraine’s fate shadows of their own troubled history and fears that history may repeat itself.

For the foreseeable future, Poland will continue to attempt to deepen military ties with the U.S. and other NATO allies to ensure there is no question around Article 5, and state and society alike will do everything in their power to ensure that the country’s neighbors to the east are free and independent.

Luka Ivan Jukic is a freelance journalist and consultant focused on Central and Eastern Europe. Jukic is currently a postgraduate student at the School of Slavonic and East European Studies at University College London. He also covers Croatia for poll aggregator Europe Elects, where he previously covered Montenegro and Serbia as well. He tweets at @lijukic.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of the New Lines Institute.