Since May 2014, when Chinese Communist Party Secretary Zhang Chunxian announced the People’s War on Terror in the Uighur region, Chinese technology firms have received billions of dollars in Chinese state capital to build a comprehensive Muslim “re-education” system in Northwest China. Over the same period of time they have created a wide range of computer vision and data analysis tools which have the potential to change forms of policing and incarceration in many places around the world. These innovations, however, have come at the cost of what U.S. lawmakers describe as “crimes against humanity.”

Technology’s Double-Edged Sword

The global COVID-19 pandemic has made clear that Chinese technology companies are at the cutting edge of surveillance innovation and predictive analytics. In April 2020, Amazon, the wealthiest technology company in the world, received a shipment of 1,500 heat-sensing camera systems from the Chinese surveillance company Dahua. Many of these cameras, which are worth approximately $10 million, will be installed in Amazon warehouses to monitor the heat signatures of employees and alert managers if workers exhibit COVID-19-like symptoms. Other cameras included in the shipment will be distributed to IBM and Chrysler, among other buyers.

In 2017, Dahua received over $900 million to build comprehensive surveillance systems which supported a “re-education” system of extra-legal internment, checkpoints, and ideological training for Muslim populations in northwestern China. Since then, the U.S. Department of Commerce placed it on a list of companies banned from buying or selling in the United States. Yet despite the legal and ethical ramifications of buying products from Dahua, Amazon continues to do business with them.

With the help of Dahua and hundreds of other private and public Chinese companies, as many as 1.5 million Uighurs and Kazakhs have been “disappeared” into a widespread system of “re-education camps” in the Uighur Autonomous Region (Xinjiang).[1] Nearly all Uighurs and Kazakhs in China have an immediate family member who is, or has been, interned in this camp system. Uighurs now refer to themselves as a “people destroyed.” As I observed during a research trip to the region in 2018, many Uighur-owned businesses have closed across the country. Whole streets have been abandoned in Uighur towns and villages. Because of the re-education system, it is likely that within a single generation Muslim embodied practice and Turkic languages in Northwest China will cease to provide essential ways for Uighurs and Kazakhs to sustain their knowledge systems.[2] This process affects every aspect of their lives not only due to mass detentions, but also because of the way biometric and data surveillance systems supporting the camps have been used to monitor and transform their behavior.[3]

This terrain assessment describes how Turkic Muslims in Xinjiang were targeted by digital and biometric surveillance technologies of the “re-education” system. Its main conclusion is that the world is witnessing the birth of a new form of technology-enabled systems of social and behavioral control. This rise in authoritarian statecraft coincides with breakthroughs in face surveillance, voice recognition, automated data recovery tools and algorithmic assessments of social media histories in China’s private and public technology industry.

How Do Surveillance Systems Target Turkic Muslims?

Many of the dozens of former detainees and inhabitants of the region I interviewed while researching the technological aspects of the re-education system said that they or those they knew were detained because of digital texts, audio clips, and videos that they had shared on their smartphones.iv In numerous cases, former detainees told me they met people in the camps who were detained because they had used their ID card to register multiple SIM cards, they had installed Facebook or WhatsApp on their Android phones, or they had used Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) to circumvent China’s “great firewall.” All of these “pre-crimes” could be construed as part of a list of 75 official signs of Islamic extremism. Police departments across the region began to employ “police contractors” to check people’s devices using artificial intelligence-enabled auto-recovery tools built by the Chinese tech giant Meiya Pico and others.[4] State workers and automated data collection systems fed this information into a region-wide Integrated Joint Operations Platform (IJOP). Authorities used this system, along with data collected through interrogations, to determine which Muslims were “unsafe” and in need of detention.[5]

Inside the formal “re-education camps,” detainees were subjected to comprehensive monitoring.[6] The lights inside their cells were extremely bright. They were never turned off. In interviews, former detainees who were held in camps across the region told me that at no point during the day or night were detainees permitted to obscure the view of their faces from the cameras. If they covered their eyes with their hand or a blanket they would receive an immediate warning from a guard via the speaker system in the cell.

They were living in what analysts of the computer vision company Megvii refer to as a “smart camp” or barracks – a facility that the tech firm Dahua says is supported by technologies such as “computer vision systems, big data analytics and cloud computing.”[7] According to a camp manual, approved by Zhu Hailun, the deputy party secretary of the Uighur region, these camps are to “perfect peripheral isolation, internal separation, protective defenses, safe passageways and other facilities and equipment, and ensure that security instruments, security equipment, video surveillance, one-button alarms and other such devices are in place and functioning.” As the new regional Party Secretary Chen Chuanguo was quoted as saying, the camps should “teach like a school, be managed like the military, and be defended like a prison.”

The experiences of my interviewees suggest that “smart prison” face recognition is being used on them in the camps. According to documents from the company Lonbon, face recognition and so-called “emotion or affect recognition” technologies have been installed throughout the Uighur region prison system. [8] Given the active obfuscation of the evidence of the re-education system in the region, it is difficult to determine if face recognition systems are being used in all camps or in what Lonbon refers to as “correction centers”–a euphemism that is sometimes used for camps in Northwest China.

People who were not immediately detained were nevertheless ordered to go to local police stations and clinics to submit blood and DNA samples have their irises, faces and fingerprints scanned and a unique voice signature recorded. One Kazakh woman told me, “The village government leader told us openly that those who refused would be taken to the re-education camps.” This biometric data was then added to their citizenship file as part of a new “smart” ID card system. Once this system was fully implemented by the end of 2017, it became impossible for Uighurs and Kazakhs to enter a bank or shopping mall without having their face scanned and matched to the image on their ID at fixed checkpoints. Han people were often waved through these checkpoints without a scan, particularly in Turkic Muslim majority areas The Kazakh woman told me, “On average, over the span of a single day, I had my ID and face scanned more than 10 times.”

It is unclear how all of this data is used. As James Leibold has noted, there is likely a significant gap between the advertised capacities of the systems in place and their actual ability to turn biometric and digital data into actionable forms of social control.[9] Much of the data in the IJOP system is input manually or through targeted scans of smart phones, while other forms of data are fed into the system through banking records, GPS tracking and license plate and face recognition camera systems. Yet despite potential gaps in purported knowledge and technical capability, the ubiquity of checkpoints and cameras make Turkic Muslims modify their behavior in their daily life and reorient their activities around ideals promoted by state authorities. The technologies begin to create a new reality.

The Logic of Chinese Counterterrorism

The history of Chinese counterterrorism is born largely out of post-9/11 counterinsurgency theory (COIN). Soon after U.S. Army General Petraeus crafted a new counterinsurgency field manual in 2007, Chinese military and policing scientists began to consider what they could learn from a new approach to asymmetrical warfare. They considered central COIN principles such as full spectrum intelligence; placing people in categories of insurgent, neutral, and pro-regime change populations; breaking up social networks through targeted detentions; and “winning the hearts and minds” of those who remained.[10]

As elements of counterinsurgency theory were implemented in the United States and Europe in the form of Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) programs that strove to “deradicalize” Muslim citizens, Chinese policing theorists began to think more about “preventative policing” and the way surveillance and education systems could be used to transform non-Han Muslim populations.[11] Building on an intelligence-led policing program called the Golden Shield project that had already been established post-9/11, they took note of Edward Snowden’s revelations of the PRISM mass data analytics project that collected and assessed data from social media both in the United States and around the globe.

As violent Uighur protests continued to grow between 2010 and 2016 in response to police brutality, religious oppression and land seizures, [12] widespread smart phone use among the Turkic Muslim population in China and breakthroughs in surveillance technologies made a new form of COIN and CVE with “Chinese characteristics” a possibility. Of course, the mass scale with which they enacted them at the capillary grassroots of Turkic Muslim society drew not just from Euro-American policing science and technological capabilities, but also from Maoist-legacy social engineering. As James Leibold has noted, Chinese authoritarian statecraft has long centered on a violent paternalism that pathologizes behavior, thought, and emotions deemed deviant and tries to forcefully transform it.

The Role of Private Industry

Drawing directly on lessons learned in the war in Iraq and from American CVE programs, local Chinese authorities in the Uighur region began outsourcing their policing responsibilities to private and state-owned technology companies in order to enhance their surveillance capacities.[13] These Private Public Partnerships (PPPs), which were thought to be more nimble and responsive to economic and political challenges than socialist-legacy State Owned Enterprises (SOEs), were funded by the central and regional government. By 2017, the Chinese state had invested more than $2.6 trillion in PPPs in a wide range of infrastructure projects across the country.[14] The Uighur region led the country in PPP contracts given to private technology firms. They used these funds to develop new surveillance and analytics tools as part of Safe City projects that supported the new system of Turkic Muslim “re-education.”[15] Although the state froze funding for some of these projects near the end of 2017, by 2018 the market for security and information technology in the region grew to an estimated $8 billion with close to 1,400 private firms competing for lucrative contracts.

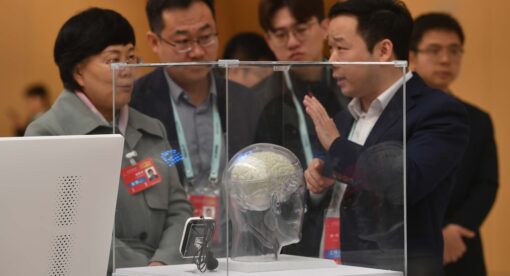

Companies which have been labeled national-level “Artificial Intelligence Champions” were particularly important in this effort.[16] These companies have been described as key to the goals of Xi Jinping’s administration in leading the world in artificial intelligence technologies by 2030. The Uighur re-education project offered many of these champions a novel space to develop predictive policing tools and experiment with biometric surveillance systems.

For instance, the AI Champion, iFLYTEK (along with hardware and service provider Meiya Pico and Fiberhome), developed tools to automate the transcription and translation of Uighur language audio into Chinese, where it could then be analyzed for pre-criminal and criminal content.[17] The computer vision analytics AI Champion, Sensetime, worked in a joint venture with a subsidiary called Sensenets to surveil over 2.5 million inhabitants of the Uighur region using face surveillance technologies across the region. According to a company spokesperson, the company’s software was “being used in Xinjiang” where they received “some good feedback.” [18] Megvii, a rival computer vision AI Champion, developed tools to create “smart camps” and support surveillance video analytics.[19] Another computer vision AI Champion YITU used a project called Dragonfly Eye to draw on a data set of over 1.5 billion faces in order to automate the detection of Uighur faces (other companies called Cloudwalk, Intellifusion also attempted to do similar forms of automated profiling).[20] Another AI Champion, HikVision, a subsidiary of the SOE military supplier China Electronics Technology Company, received nearly $300 million in state contracts to develop “Safe City” surveillance systems with “zero blank spaces” throughout the Uighur-majority areas.

In a post-9/11 world, these Chinese tech firms are not alone in using surveillance technology to automate policing of populations deemed dangerous. However, they do have what they view as a strategic advantage over North American and European technology firms in that they have a space to experiment with these technologies without fear of legal or civil resistance, or without shareholders holding them responsible for failed systems. China’s counterterrorism laws obligate Chinese social media and technology companies to provide policing agencies complete access to user data. Furthermore, the widespread private contracting of public services throughout the post-2014 Chinese economy has produced a market structure in which the majority of profits for technology firms come not from consumer products and services, as in Western contexts, but from infrastructure projects. In 2016, approximately $52 billion of the security technology market in China was structured around such projects, while $32 billion came from security products and $6.8 billion came from alarm systems.

Ultimately, the Chinese technology industry is shaped by an authoritarian statecraft. In 2017, state authorities spent more than $197 billion on domestic security, excluding spending on security-related urban management and surveillance technologies initiatives. Policing per capita in the Uighur region itself now exceeds that of East Germany before the fall of the Berlin Wall. What makes this comparison even more troubling is that the police, the majority of whom are privately-hired low-wage police contractions with little to no training [21], are supported by technology systems and an economy which are far more powerful than those available to the Stasi.

Halting These Surveillance Systems

In October 2019, the U.S. Department of Commerce placed eight technology firms involved in the extra-legal detention of Muslims in China on an entities list, blocking them from all trade with firms in the United States. In May 2020, they extended this list to include a textile company and eight more tech firms. These included the five “AI Champions” named above.

While these targeted sanctions have introduced a moral and material cost to these companies and those with whom they trade, they have not been enough to halt the systems they designed and implemented. In fact, while these firms have been forced to source parts elsewhere and work through intermediaries to maintain market share, in many instances they continue to sell consumer products in the United States.

What makes halting these systems even more difficult are the deep connections between the Chinese companies that built them and American institutions, military programs, and private companies. For instance, as recently as 2019, the U.S. Army and U.S. Navy have funded joint research with Chinese AI Champions which are on the entities list. U.S. institutions such as MIT continue to accept funding from these companies, despite their complicity in egregious human rights abuses.

These linkages extend beyond educational institutions to the U.S. technology industry itself. Many of the leaders of the Chinese firms received training from Western universities, or worked in the U.S. industry or institutes funded by U.S. companies such as Microsoft Research Asia and IBM Research before developing surveillance tools for authoritarian control in China. Many of them continue to do research and publish with their Western counterparts. For instance, the director of research at Megvii USA has published articles with current researchers at the University of Wisconsin, Stanford, Duke, Georgia Tech, Brown, and Rutgers. He has also co-published with researchers at Facebook, Google, and Adobe, among others. In nearly all cases, the leaders of these sanctioned companies are deeply embedded in the U.S. research community and tech industry.

In some cases, these partnerships may have ceased after their involvement in what congressional leaders and the United States Holocaust Museum have declared a “crime against humanity” was made clear. Yet, a cursory investigation reveals that many joint collaborations between American researchers and employees of these firms are ongoing; even more problematically, all major technology journals aside from those published by Springer Nature and Wiley appear to continue to accept research articles from these entities without consideration of the ethics of the research or researchers.

Ultimately this calls into question the complicity of the US technology industry and the research institutions that support it. In 2019, an investigative report revealed that Microsoft was funding a surveillance company called AnyVision which tracked the physical and virtual activities of Palestinian citizens without their consent. Google provides mapping services to the private prison company BI Incorporated, which tracks asylum seekers at the southern border of the United States. Only global political and economic reform beginning in the U.S. tech industry and its related institutions – reform that implements greater transparency, accountability, and regulatory oversight – will halt the rise of new, technology-enabled harm to vulnerable populations. Such a movement will involve a combination of international coalition building and grassroots pressure to reshape global technology systems.

Policy Recommendations

These steps should be taken to bring about an end to the technological systems developed and implemented to harm Turkic Muslims living in northwestern China.

First, there must be a fuller implementation of the sanctions enacted by the entities list. This means that consumer products manufactured by the companies on that list should no longer be sold in the U.S. marketplace. As it has done regarding Confucius Institutes on college campuses, the U.S. government should use funding leverage to apply pressure to U.S. universities, publishers, and research institutes to cease collaborating with these companies. They must enforce these sanctions through civil and criminal prosecution.

Second, detailed reports of current state of the re-education system are necessary. Both houses of the U.S. Congress have passed the Uighur Human Rights Policy Act. This bill extends Magnitsky sanctions against key leaders in the re-education system. It also commissions a full investigation not only of the camp system and technology firms involved, but also the role of Uighur forced or unfree labor in producing garments and consumer technologies sold in the U.S. market as part of the system.

Third, A second bill, the Uighur Forced Labor Prevention Act of 2020, must also be passed by the U.S. Congress. This new bill requires that the U.S. administration act within 120 days to identify and extend sanctions on all companies and state entities involved in the forced labor system.

Fourth, As a result of these reports and passage of the forced labor bill, many other firms should be targeted with sanctions. So far, the entities list includes only 17 Xinjiang-related companies. There are likely as many as 1,400 tech firms who are involved in the re-education system and hundreds of manufacturing companies. All products from companies involved in the following activities as relates to Muslim minority citizens in China should be subjected to comprehensive sanctions: involuntary surveillance; assessment and restriction of digital communications; monitoring or restricting individual movement, travel and religious practice; involuntary identification of individuals through facial recognition, voice recognition, or biometric indicators; and forced or unfree labor of workers controlled by the above systems.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly in light of the global future of political and carceral technologies, the U.S. government should introduce legislation, and work with partner nations, to universally ban the use of “passive” or involuntary biometric information and data surveillance. Washington should work with allies around the globe to introduce a new legal instrument that will ensure global protections for humans from such surveillance technologies and requisite penalties for failure to maintain such standards. This would have the effect of making both U.S. tech companies and Chinese companies comply with universal standards.

Darren Byler is a post-doctoral fellow at the Center for Asian Studies, University of Colorado, Boulder, where he studies the effects of Chinese infrastructure and security technology as part of the China Made Research Initiative. His book project titled “Terror Capitalism: Uyghur Dispossession and Masculinity in a Chinese City” (Duke University Press, 2021) focuses on the effects of digital cultural production, surveillance industries and mass internment in the lives of Uighur and Han male migrants in the city of Urumchi, the capital of the Uighur Autonomous Region (Xinjiang). He has published research articles in the Asia-Pacific Journal, Contemporary Islam, Central Asian Survey, The Journal of Chinese Contemporary Art and contributed essays to volumes on the ethnography of Islam in China, transnational Chinese cinema, travel and representation. In addition, he has provided expert testimony on Uyghur human rights issues before the Canadian House of Commons Subcommittee on Human Rights and writes a regular column on Turkic Muslim society and culture for the journal SupChina.

UPDATE: This article has been updated to reflect new information from investigative journalist Kai Strittmatter indicating that Sensetime, rather than Megvii, openly admitted that their software was used in Xinjiang.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of the Newlines Institute.

Endnotes

[1] Famularo, J. (2018). ‘Fighting the Enemy with Fists and Daggers’: The Chinese Communist Party’s Counter-Terrorism Policy in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. In Terrorism and Counter-Terrorism in China: Domestic and Foreign Policy Dimensions. Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordscholarship.com/view/10.1093/oso/9780190922610.001.0001/oso-9780190922610-chapter-003 and Zenz, A. (2019). ‘Thoroughly reforming them towards a healthy heart attitude’: China’s political re-education campaign in Xinjiang. Central Asian Survey, Vol. 38(No. 1), 102–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/02634937.2018.1507997 [2] For more on the goals of the “re-education” system see Zenz, A. (2019). Brainwashing, Police Guards and Coercive Internment: Evidence from Chinese Government Documents about the Nature and Extent of Xinjiang’s “Vocational Training Internment Camps.” Journal of Political Risk, Vol. 7(No. 7). https://www.jpolrisk.com/brainwashing-police-guards-and-coercive-internment-evidence-from-chinese-government-documents-about-the-nature-and-extent-of-xinjiangs-vocational-training-internment-camps/; for family separations see Zenz, A (2019), Break Their Roots: Evidence for China’s Parent-Child Separation Campaign in Xinjiang, Journal of Political Risk, Vol. 7(No. 7); “China: Xinjiang Children Separated from Families”, Human Rights Watch, 15 September 2019, https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/09/15/china-xinjiang-childrenseparated-families [3] Millward, J. A. (2018, February 3). What It’s Like to Live in a Surveillance State. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/03/opinion/sunday/china-surveillance-state-uighurs.html; Byler, D. (May 2019). Ghost World. Logic Magazine. https://logicmag.io/china/ghost-world/; “China’s Algorithms of Repression,” Human Rights Watch, 01 May 2019, https://www.hrw.org/report/2019/05/01/chinas-algorithms-repression/reverse-engineering-xinjiang-police-mass-surveillance [4] Between January 2019 and May 2020 I interviewed more than a dozen former detainees and dozens of their relatives in Kazakhstan and in North America. [5] See note 27 for more on Meiya Pico. [6] Unlike most interrogation or detention centers that many Turkic Muslims were held in prior to being transferred to the camps. [7] Dahua and other companies involved in Xinjiang also advertise their “smart camp” capabilities, see “Dahua Professional Industry Smart Camp Project,” Dahua Technology Co., Ltd., https://www.dahuatech.com/cases/info/529.html and “Smart Security, National Security” Aerospace Huatuo Technology Co., Ltd. Oct. 2019, http://www.htrfid.com/About/newsinfo/id/165.html [8] To be clear “mood recognition” systems have not been shown to be reflective of the emotional states of those they target. Here I am simply documenting that this is how employees at “smart prison” companies describe their systems’ capabilities. See “Smart Prison – Xinrui Wireless and the Deep Integration of Police Management-Computer Room Products”. Shenzhen Yilu Information Technology Service Co., Ltd. (May 2018). http://www.eroadict.com/solution_view.aspx?FId=t25:30:25&Id=461&TypeId=30&IsActiveTarget=True; Wang, F. (2019). “Smart Prisons” Are Here, Are You Ready?,” http://archive.vn/lsR1Q; “The Video Intercom System of LonBon Won the Bid in Seven Prisons in Xinjiang!,” 21 November, 2017, http://archive.fo/571tE#selection-2567.238-2575.20 [9] Leibold, J. (2020). “Surveillance in China’s Xinjiang Region: Ethnic Sorting, Coercion, and Inducement.” Journal of Contemporary China, Vol. 29(No, 121), 46-60. [10] xvi For more on COIN see Harcourt B. E. (2018). The Counterrevolution: How Our Government Went to War against Its Own Citizens. Basic Books. For more on the way it was taken up by Chinese policing scientists see Lu, Peng L. and Xuefei Cao X. (2014). An Analysis of Israel’s Anti-terrorism Strategy and How it Inspires China’s Xinjiang Anti-terrorism. Journal of the National Police University of China, no. 1, 19–21. [11] For more on CVE programs see Arun K. and Hayes, B. (2018). The Globalisation of Countering Violent Extremism Policies: Undermining Human Rights, Instrumentalising Civil Society. Transnational Institute. https://www.tni.org/files/publication-downloads/the_globalisation_of_countering_violent_extremism_policies.pdf. For more on the way CVE programs were adapted and utilized to transform Uighur society see Shan, D. and Ding W. (2016). Studies on Anti-terrorism and the Xinjiang Mode. Journal of Intelligence, Vol. 35(no. 11), 20–26. [12] For a recounting of this see Roberts S. R. (2018), The Biopolitics of China’s ‘War on Terror’ and the Exclusion of the Uighurs,” Critical Asian Studies, Vol. 50(No. 2), 232-258. [13] See for example an article featuring interviews with the chief technology officer of Alibaba and the founder of iFLYTEK, both AI Champions, discussing their respective roles in countering the threat of Uighur violence through assessments of calls, traffic, shopping, dating, email, chat records, videos, language and voiceprint detection. Zhang, Z. R. (2014). Big Data Counter-Terrorism has Become an International Trend, Xinhua, http://news.sciencenet.cn/htmlnews/2014/3/289312.shtm [14] Jie, T. and Zhao, J.Z. (2019). The Rise of Public–Private Partnerships in China: An Effective Financing Approach for Infrastructure Investment?. Public Administration Review Vol. 79(no. 4), 514-518. [15]“Meeting the Peak of Safe City Project Construction,” Essence Securities, 8 July 2018, http://pdf.dfcfw.com/pdf/H3_AP201807091164665904_1.pdf ; Xinjiang received 17 percent of the total share of PPPs from 2015 until 2017 according to “42 PPP Projects totaled 21.1 Billion,” Seven Transportation Network, 17 June 2017, https://www.sohu.com/a/149762456_654086 [16] As of 2019 there were 15 companies that have been named “national level AI champions” by Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology. These include: Alibaba, Baidu, Huawei, HikVision, iFLYTEK, JD.com, Megvii, MiningLamp, Qihoo, Ping An Insurance, TAL Education, Tencent, SenseTime, Xiaomi, YiTu. See “The Ministry of Science and Technology Expands the List of ‘AI National Team,’ Ten New Companies are Selected,” Network Consolidation, 30 August 2019, https://www.eet-china.com/news/201908301010.html. Of these 15 companies, 5 have been found to be complicit in human rights abuses in the Uighur region by the U.S. Department of Commerce. [17] Cadell, C. and Li, P. (May 2018). At Beijing Security Fair, an Arms Race for Surveillance Tech. Reuters, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-monitoring-tech-insight/at-beijing-security-fair-an-arms-race-for-surveillance-tech-idUSKCN1IV0OY; “Uighur-Chinese Speaking Instant Translation” Software,” China Education Equipment Network, 22 February 2016, http://www.tac-online.org.cn/index.php?m=content&c=index&a=show&catid=586&id=2608; “As of 2019 Meiya Pico Controlled Approximately 47 Percent of China’s Security Equipment Market,” Guolian Securities, 02 November 2018, http://pdf.dfcfw.com/pdf/H3_AP201811071238862464_1.PDF; “iFLYTEK Controls Around 70 Percent of the Chinese Market for Speech Recognition Software,” DSP Group, 2017, https://www.dspg.com/press/iflytek-device-speech-recognition-software-successfully-ported-available-dsp-groups-ultra-low-power-voice-processors/ [18] Strittmatter, K. (2019). We Have Been Harmonized. Old Street Publishing, 170. [19] “A Bird’s Eye View of the Artificial Intelligence Market,” Yiou Intelligence,, September 2017, http://img1.iyiou.com/ThinkTank/2017/HowAIBoostsUpSecurityIndustryV6.pdf. Other companies heavily involved in Xinjiang such as Dahua also advertise their “smart camp” capabilities, see see “Dahua Professional Industry Smart Camp Project,” Dahua Technology Co., Ltd., https://www.dahuatech.com/cases/info/529.html and “Smart Security, National Security” Aerospace Huatuo Technology Co., Ltd. October 2019, http://www.htrfid.com/About/newsinfo/id/165.html http://www.htrfid.com/About/newsinfo/id/165.html. In a statement Megvii Vice President Xie Yinan denies that Megvii is involved in “controlling locals,” but at the same time acknowledges that their technology has been sold to Public Security Bureaus across the country: Schmitz, R. (Apr. 2018). Facial Recognition In China Is Big Business As Local Governments Boost Surveillance. NPR, https://www.npr.org/sections/parallels/2018/04/03/598012923/facial-recognition-in-china-is-big-business-as-local-governments-boost-surveilla. These cooperations include Xinjiang. Zheng Wei (ed.) (Dec. 2017). “Artificial intelligence provides a new kinetic energy to urban development. Megvii’s Face++ technology helps to build a ‘city brain’” Xinhua: China Net, http://archive.fo/msIhN. Megvii now argues that their code was included in Xinjiang systems without their permission and was not operationalized: “China’s Algorithms of Repression,” Human Rights Watch, 01 May 2019, https://www.hrw.org/report/2019/05/01/chinas-algorithms-repression/reverse-engineering-xinjiang-police-mass-surveillance.This statement is contradicted by other statements that simply seek to downplay their role in Xinjiang, implying that their past involvement in human rights violations should not be held against them: “US Blacklist is Not Stopping Megvii from Seeking a Hong Kong IPO,” Al Jazeera, 19 November, 2019, https://www.aljazeera.com/ajimpact/blacklist-stopping-megvii-seeking-hong-kong-ipo-191119185927551.html. [20] Mozur, P. (2019). One Month, 500,000 Face Scans: How China Is Using A.I. to Profile a Minority, New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/14/technology/china-surveillance-artificial-intelligence-racial-profiling.html; “Yitu Technology: Artificial Intelligence Expands Future Boundaries,” YITU, 22 March 2018. [21] Leibod, J and Zenz, A. (2019). Securitizing Xinjiang: Police Recruitment, Informal Policing and Ethnic Minority Co-Optation.” The China Quarterly, 1-25.