Listen to article

Bangladesh, a large and growing country in a geographically vital location, will be an important asset amid the great-power competition unfolding across Asia. U.S. policymakers would be well advised to begin paying closer attention to it – while also recognizing and contending with several significant challenges.

Bangladesh has continually experienced prolonged periods of political instability, corruption, and human rights violations. The country is facing a growing extremist threat, and its increasingly authoritarian government has exacerbated many of the problems that have stifled its potential to become an influential global actor. The United States can help Bangladesh overcome its democratic deficit by helping strengthen its state institutions, paying closer attention to the ruling party’s authoritarian excesses (including its reversal of secular values for the sake of political expediency), and supporting the fulfillment of vital humanitarian needs.

Political Rivalries

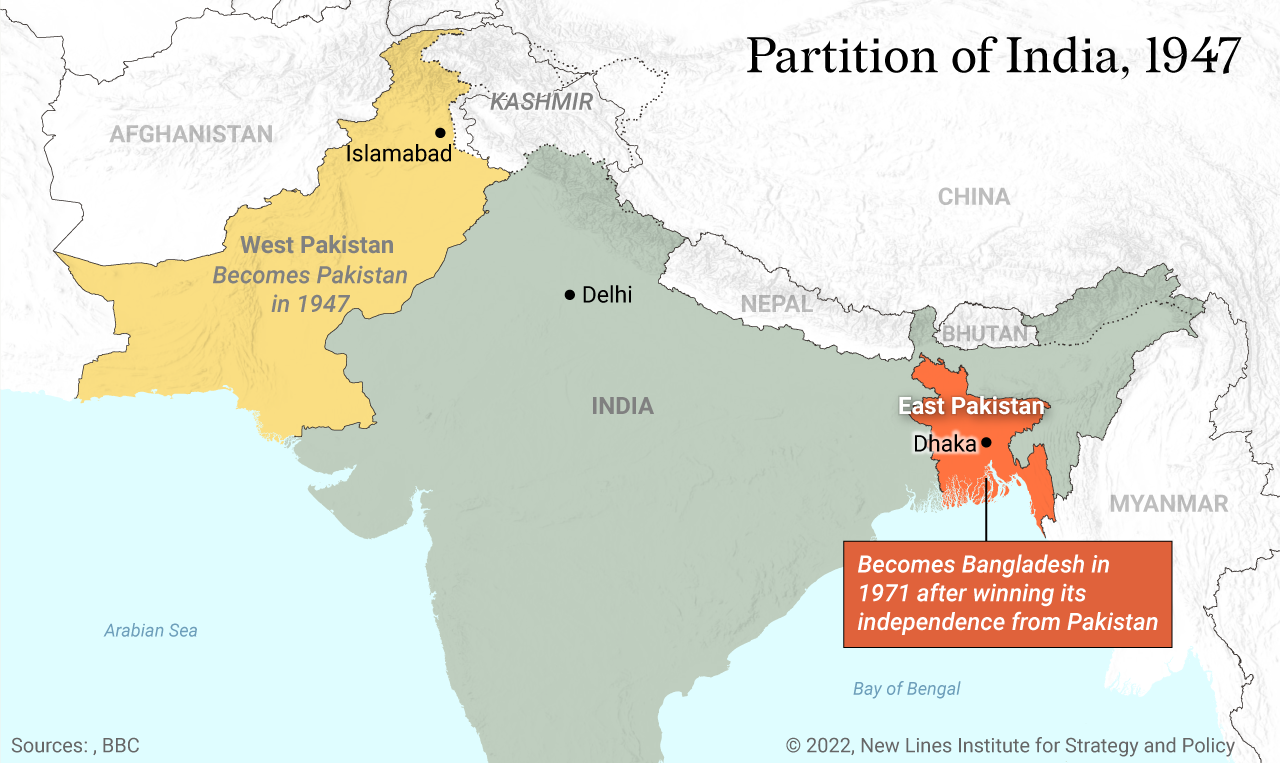

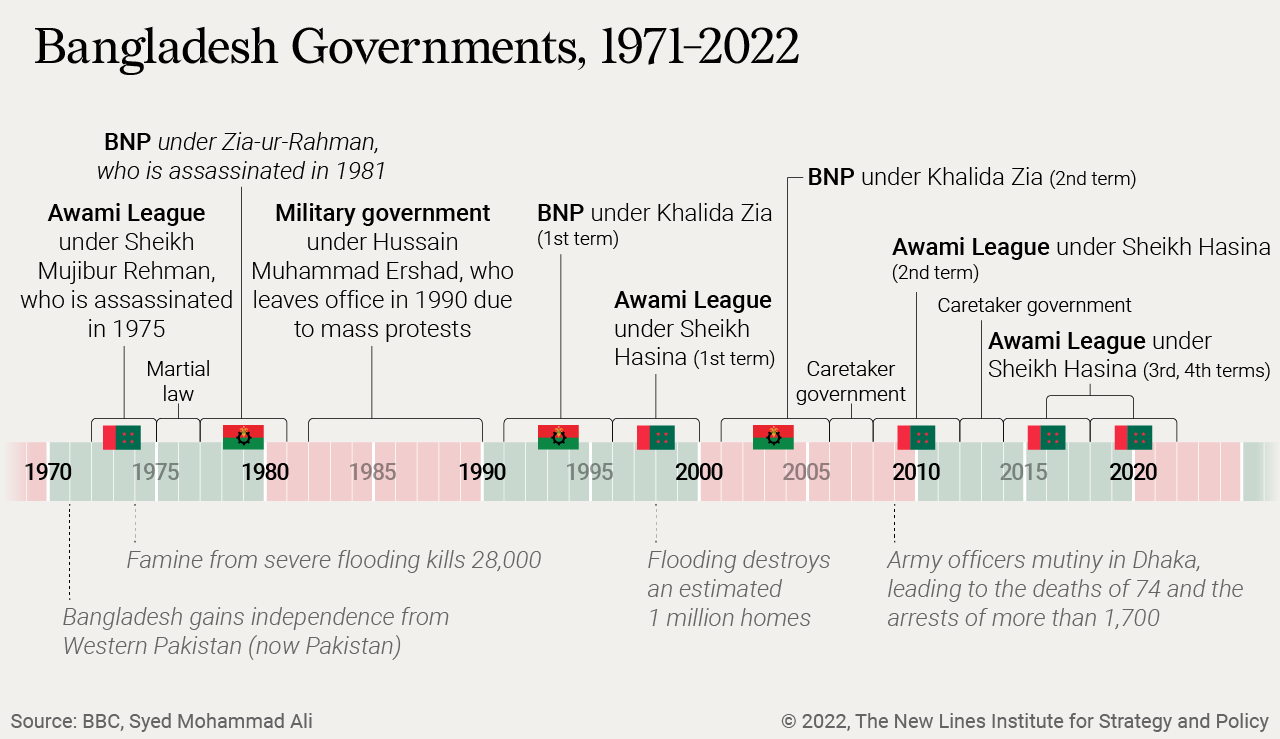

East Pakistan, as Bangladesh was called when it came into being in 1947 with the British-administered partition of the Indian subcontinent, was primarily carved out of the larger state of Bengal, and it was separated from West Pakistan by over 1,000 miles of Indian territory. Growing disgruntlement over the hegemonic policies of its western wing finally led East Pakistan, led by Sheikh Mujeeb-ur-Rahman, to declare independence from its co-religionists in West Pakistan in 1971.

Bangladesh’s democracy is fragile, afflicted by rampant political violence. Its leader, Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, the daughter of Mujeeb, also heads the ruling party known as the Awami League. Under Hasina’s leadership, the Awami League has demonstrated disturbingly authoritarian tendencies and has used all means necessary to quash its political opponents.

The Awami League is locked into a protracted rivalry with the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), the origins of which can be traced back to the military coup in 1975 that led to Mujeeb’s assassination. Zia-ur-Rahman assumed power after Mujeeb’s death, forming the BNP as a center-right nationalist party. Rahman’s widow now heads the BNP, which has used religious/political entities like the Jamaat-e-Islami to widen its base of support in opposition to the Awami League. The Awami League, in turn, has adopted an antagonist stance against the Jamaat-e-Islami. The Awami League resents the Jamaat-e-Islami’s longstanding alliance with the BNP and the Jamaat-e-Islami’s alleged support for West Pakistan during the 1971 war for Bangladesh’s independence.

The Awami League and BNP have alternated in government since the early 1990s, except for a military-supported caretaker regime that postponed 2007’s parliamentary elections. BNP’s Khalida Zia was prime minister twice (from 1991-1996 and again from 2001-2006). Hasina first became prime minister in 1996 and returned to office in 2008, where she has remained, leaving Bangladesh under the ever-tightening grip of one party led by one leader.

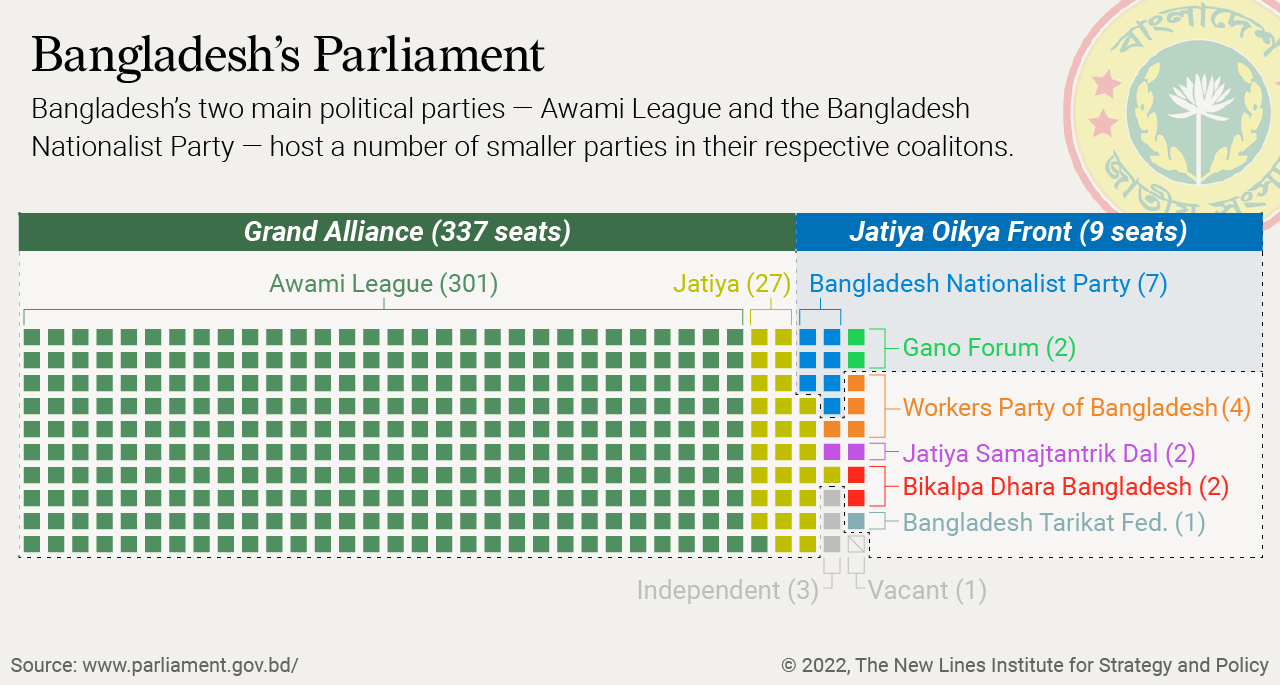

The Awami League has managed to remain in power with the support of a broad-based coalition of 14 political parties, known as the Grand Alliance. However, while the Awami League has kept this alliance intact, it continues to engage in evident political repression of its opponents, with ample evidence of ongoing political violence across Bangladesh. The International Crisis Group cited 14,000 incidents of political violence in Bangladesh from 2002 to 2013, which killed more than 2,400 people and injured 126,300. Widespread allegations of vote tampering and other irregularities followed general elections in 2014 and 2018.

The next general elections are scheduled for December 2023, but the newly formed Election Commission, which is meant to oversee them, does not evoke much confidence among the opposition parties, which were not consulted during its formation. The BNP has also alleged that the chief election commissioner is an Awami League loyalist. With Khalida Zia declining in health, the BNP could suffer another electoral blow in 2023. Smaller parties such as the Liberal Democratic Party seem unable to offer the Awami League any serious competition either. Bangladesh’s political landscape may thus remain under the shadow of a one-party authoritarian regime, which does not bode well for the democratic health and longer-term economic prospects of the country.

Erosion of Institutions

One-party rule in Bangladesh has been accompanied by an erosion of major institutions of the state, including the police and judiciary. Political interference in the recruitment, posting, and promotions processes within the police forces enable the Awami League to exert control over the institution and use it to pressure political opponents while blocking investigations of people associated with it. Political workers remain at severe risk of abuse in police custody, and Bangladeshi police are suspected of registering “fake cases” to harass political workers. In 2019, the BNP’s senior joint secretary claimed that the police had filed false cases of violence and rioting against as many as 2.5 million BNP affiliates over the preceding decade, just to prevent them from engaging in political activities. While the above cited number lacks substantiation, independent human rights entities do recognize that the Awami League relies on the state’s security apparatus to counter dissent.

The Rapid Action Battalion, an elite paramilitary force ostensibly created to contend with lawlessness and terrorism, has been politicized and increasingly come to symbolize heavy-handed and politically motivated law enforcement. The battalion has been repeatedly accused of detaining political workers in undisclosed locations for significant periods before filing formal charges and bringing them to court, of engaging in extrajudicial killings, and of enforced disappearances.

The Awami League has also subverted the judiciary. Several judges have been transferred or threatened with administrative action by law ministry officials for any perceived signs of leniency toward opposition members. The Awami League is also said to use violent student and labor wings (such as the Chhatra League and Jubo League) to attack its political opponents.

Two years after regaining power in 2008, the Awami League founded an International Crimes Tribunal (ICT) to put on trial those accused of having committed crimes against humanity during the 1971 conflict, when Bangladesh gained independence from Pakistan. The ICT received hundreds of allegations, and by 2013 it began delivering verdicts branding BNP and Jamaat-e-Islami leaders as war criminals, with some even receiving death sentences. Every time the tribunal passed such a decision, it unleashed violent opposition across the country. Human rights agencies expressed concern about how ICT cases were being handled and called for amendments to the ICT rules to ensure that the trials complied with international standards, but these concerns were mostly brushed aside.

In 2013, the Awami League also used its leverage over the apex courts to revoke Jamaat-e-Islami’s status as a political party, and the Awami League-led government banned the Jamaat-e-Islami from contesting the 2018 elections. The Jamaat-e-Islami maintains political relevance through its alignment with the BNP, but this in turn is a major reason why Jamaat-e-Islami party affiliates continue to face repression.

The Awami League has even accused the BNP of aligning itself with extremist militant groups such as Jamatul Mujahedeen Bangladesh, which aims to replace the government of Bangladesh with its own version of an Islamic state ruled by a myopic interpretation of shariah. The acrimonious power struggle between the Awami League and the BNP has cast doubts concerning the authenticity of such charges, especially given that the Awami League has been known to use state institutions and the imperative of fighting “terrorism” to persecute and discredit the BNP and the Jamaat-e-Islami, which the Awami League has accused of being backed by Pakistan’s intelligence agencies. After a high-profile attack in Dacca in 2016 by al Qaeda, the Awami League (including Hasina) underplayed the threat of the group’s Bangladeshi arm and instead pointed the finger at the BNP.

While the Awami League persecuted Jamaat-e-Islami and BNP affiliates by accusing them of being terrorists, it has reached out to other right-wing religious parties to shore up support. In the lead-up to the 2018 elections, for instance, the Awami League reached out to groups like the Jatiya Oikya Manch, a grouping of rightist parties, as well as to Hefazat-e-Islam (HeI), a fundamentalist group advocating for the “Islamization” of Bangladesh. The Awami League’s strategic compromise with these right-wing extremist groups began to increase intolerance in Bangladeshi society, sparking repeated instances of violence against minorities. Hasina nevertheless continued to provide dangerous forms of appeasement to the HeI, such as removing a statue of a woman symbolizing justice from the Supreme Court in 2017 and arresting bloggers accused of blasphemy. However, the HeI’s increasing assertiveness, including its opposition to “un-Islamic” statues of Mujeb, has brought it to loggerheads with the government, leading to the arrests of several HeI activists on vandalism charges.

Besides fueling internal intolerance, the HeI has also attempted to sabotage the Bangladeshi government’s relations with India due to its persecution of Muslims, and with western countries due to their alleged Islamophobia. HeI organized violent protests during Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Bangladesh last year that led to a dozen deaths. The group has been at the forefront of protests against publication of caricatures of Prophet Muhammad in western media, and it has pressured the Bangladeshi government to cut ties with countries that allow or defend the publication of such caricatures. Extremist groups such as the HeI are using violence to try to nudge the Bangladeshi state toward their myopic vision of Islamic governance.

However, it is likely that the HeI may become a more threatening anti-state force despite major concessions granted by the AI, which will further erode Bangladesh’s founding democratic and secular principles. The persecution of mainstream politicians by the Hasina government has in fact created a vacuum in the Bangladeshi political arena, which is being increasingly filled by dangerous religious extremists. Analysts also blame the Awami League’s tight grip over Bangladeshi politics for increasing societal intolerance and random acts of violence as legitimate means to express dissent have been increasingly stifled.

Bangladesh’s 1972 Constitution lists secularism as one of its founding principles, but Islam was declared the state religion of Bangladesh in 1988, when the country was ruled by Gen. Hussain Muhammad Ershad. Despite calls for the restoration of the “secular” provision by progressive elements within Bangladeshi civil society, it is unlikely that Hasina will capitulate, fearing alienation of conservative blocs ahead of the 2023 elections.

It is vital that Hasina’s chokehold over national politics is challenged and loosened. This does not mean that the Awami League must be defeated in the next general elections (chances of that happening remain slim), but it does mean that the international community needs to pay closer attention to the democratic deficit in Bangladesh instead of being overly impressed by the Awami League government’s seemingly secular credentials or the economic progress made under its authoritarian rule.

Supporting Bangladesh

The United States has recognized the importance of Bangladesh in recent years, but engagement remains modest. In 2012, Bangladesh and the United States initiated a partnership dialogue intended to be held annually to discuss strengthening bilateral relations based on mutual national interest. To date, eight such dialogues have been held. Hasina visited the United States in 2021 in an effort to bolster the bilateral relationship.

Diplomatic exchanges between the countries have led to increasing economic and security cooperation and equipping Bangladesh with the means to contend with the threat of climate change via affordable clean energy projects and by encouraging clean energy entrepreneurship. Climate change is not just a major threat for Bangladesh itself; climate-induced water scarcity also has the potential of creating friction with neighbors such as India, with which it shares border rivers, and which may experience an increase of Bangladeshi climate refugees if effective mitigation and resilience measures cannot be put into place. However, there is limited evidence that multilateral or bilateral donors like USAID are working on cross-border cooperation to contend with climate change in South Asia.

By taking a leading role in contending with Myanmar’s Rohingya refugee crisis, Bangladesh has received increased U.S. attention, but this remains an issue in which much more support is needed. Bangladesh has recently requested China’s support to exert its influence over Myanmar’s military junta to repatriate Rohingya refugees from Bangladesh, a move that could put the refugees in a precarious situation.

America’s interest in moderating the Chinese sphere of influence in South Asia offers another reason U.S. policymakers need to continue paying close attention to its bilateral relationship with Bangladesh. While Bangladesh has longstanding diplomatic relations with China, this relationship grew stronger after Bangladesh decided to join Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative in 2016 – a decision that resulted in significant Chinese investment. Over 500 Chinese companies are currently working in Bangladesh, many of them are working on major infrastructure projects including seaports, a river tunnel, highways, and a $3.6 billion mega-project to construct a four-mile bridge across the Padma River. Bangladesh is a major importer of Chinese products, and China has also provided duty-free and quota-free access for select Bangladeshi products to the Chinese market, which has the potential of ramping up Bangladeshi exports to China.

Bangladesh’s growing relationship with China has coincided with the souring of its relations with India as the persecution of Muslims there expands. The 2016 passage of India’s Citizenship Amendment Act, which was perceived as undermining the citizenship rights of Bengali Muslims in India, sparked major protests in Bangladesh. The United States, however, continues to provide significant aid to Bangladesh, and the country is now one of the largest recipients of American assistance in Asia. It remains in the U.S. interest to continue its engagement with and support for Bangladesh so that it does not become more dependent on China.

However, its bilateral engagement need not be provided without discernment. While the United States remains the largest source of foreign investment into the country, President Barack Obama decided in 2013 to remove Bangladesh from the list of countries that can access trade benefits under the Generalized System of Preferences scheme due to its failure to guarantee workers’ rights. The current U.S. administration has also taken note of the ongoing political repression in Bangladesh. After years of human rights violations attributed to the Rapid Action Battalion, the U.S. Treasury Department in 2021 placed sanctions on several of its former and current officials. Bangladesh was also not invited to President Joe Biden’s Summit of Democracies.

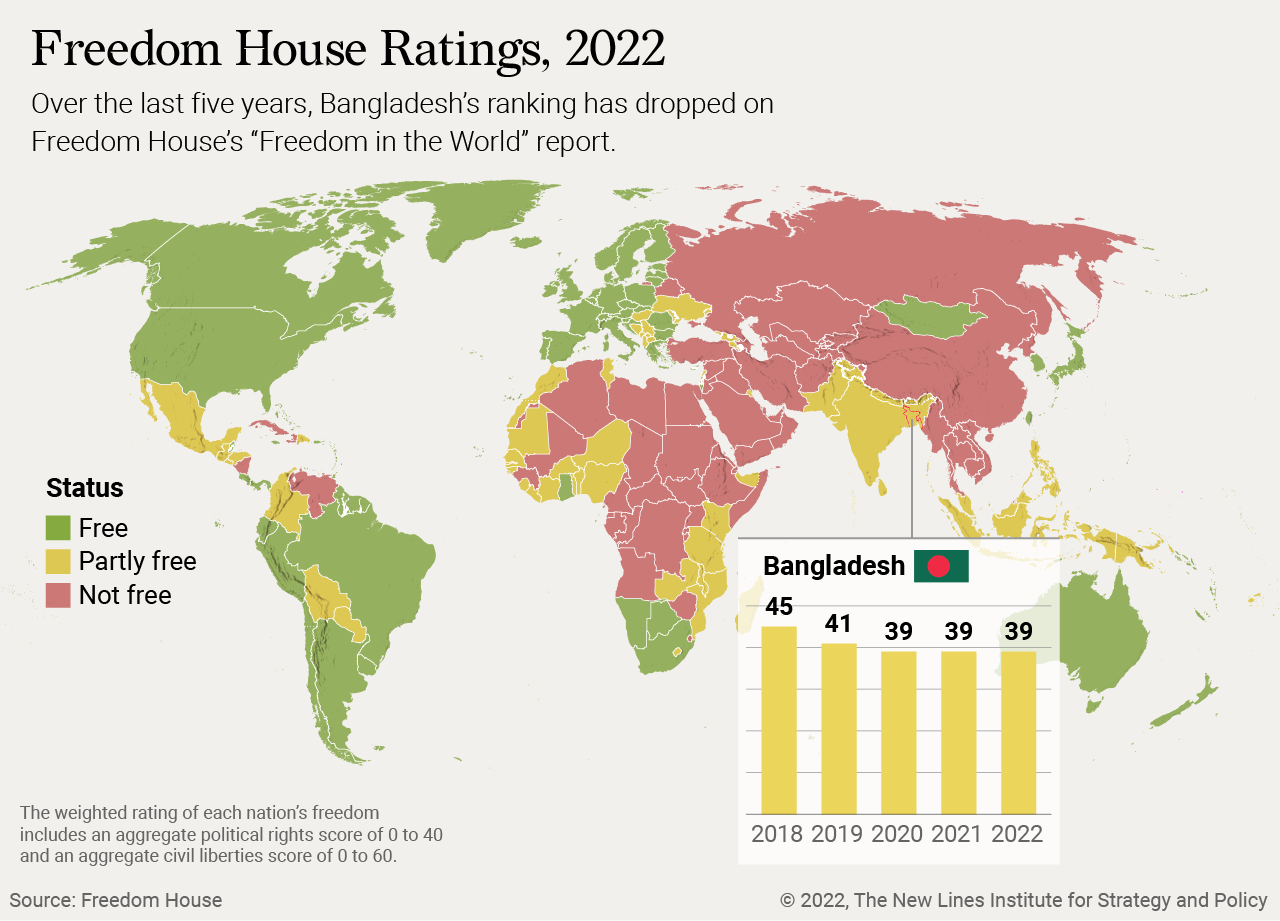

The human security situation in Bangladesh remains precarious due to authoritarian rule, political violence, corruption, and discrimination against religious minorities and Rohingya refugees. Bangladesh is thus rightly considered “partially free” by Freedom House in 2022, and its score has declined from 47 to 39 out of 100 over the past five years. This situation may worsen in the lead-up to the 2023 general elections. Despite its ranking among the fastest-growing economies in the world, the global recession and soaring fuel prices have taken a toll. Dwindling foreign reserves prompted Bangladesh to join Sri Lanka and Pakistan in seeking financial assistance from the International Monetary Fund. Economic stress prompted by IMF-imposed austerity measures, combined with growing political friction, may further exacerbate Bangladesh’s already fraught human security situation.

The United States thus needs to pay close attention to the unfolding economic situation and domestic sociopolitical environment in Bangladesh. U.S. policymakers need to continue taking steps to nudge the country into fulfilling its potential as a major pillar of democracy and secular values in South Asia, which in turn would enable it to be a valuable U.S. ally in the Indo-Pacific. For this purpose, the United States should continue to take punitive actions to curb the excesses of the ruling party as general elections approach and to draw international scrutiny to ensure they are peaceful, free, and fair.

Simultaneously, USAID can continue to work on strengthening vital institutions of the state to offset authoritarian forces within the country. While the United States is committed to helping Bangladesh contend with climate challenges at home, it can try to foster much-needed environmental cooperation to help Bangladesh manage its transboundary rivers. Supporting such cooperation between Bangladesh and India specifically seems to be the most feasible option in a region where relations among other major states remain fraught. The United States could play a constructive role in helping the two, which still have reasonably amicable ties, to bolster the Ganges Water Sharing Agreement, for example, by helping create more effective water management mechanisms, providing the increased efficiency and resilience needed to contend with climate-related challenges. Doing so may inspire other countries, including Pakistan, Nepal, and even China, to develop similar cooperative mechanisms for sharing transborder waterways, an imperative becoming more urgent as ongoing Himalayan glacial melt seriously threatens regional water supplies.

The United States should also pay greater heed to the plight of the Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh. It must apply pressure on Bangladesh to avoid forcible Rohingya repatriations to Myanmar and be prepared to commit more humanitarian assistance to help Bangladesh better cope with the refugees’ needs via multilateral agencies like the United Nations High Commission for Refugees, in addition to stepping up bilateral and NGO-funneled support.

By using a careful mix of punitive actions and supportive measures, the United States can play a constructive role in reducing political repression, offsetting authoritarian tendencies, and addressing human insecurity challenges within Bangladesh to help it attain its goal of becoming a stable middle-income nation in the foreseeable future.

Dr. Syed Mohammed Ali is a professor of anthropology, international development, and human security courses at Johns Hopkins, Georgetown, and George Washington universities. Dr. Ali has two decades of experience working on major international development challenges including governance problems, issues of marginalization, and natural and man-made disasters. Ali is the author of Development, Poverty and Power in Pakistan: The Impact of State and Donor Interventions on Farmers (Routledge, 2015).

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not reflective of an official policy or position of the New Lines Institute.