Listen to article

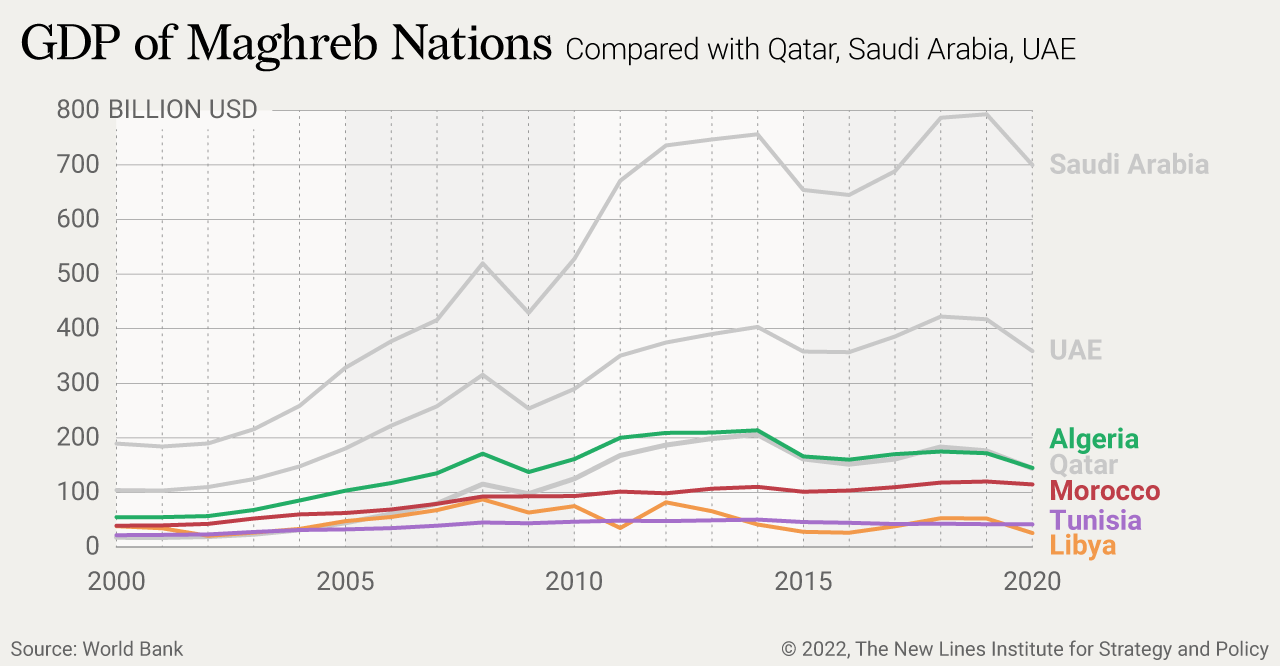

Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya have experienced political turmoil since the Arab Spring uprisings of 2011. Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, and to a lesser extent Saudi Arabia have been taking advantage of their vulnerability, thus influencing the internal and broader regional dynamics in the Maghreb. By ignoring these dynamics, the U.S. risks being adversely affected as Gulf interference weakens governance and stability in the Maghreb, which will in turn permit the growth of human rights violations, unmanageable migration flows, and extremism. By indirectly or directly encouraging the development of a stable, harmonious Maghreb, Washington can further its own strategic interests without expending additional resources.

The Maghreb’s Strategic Importance

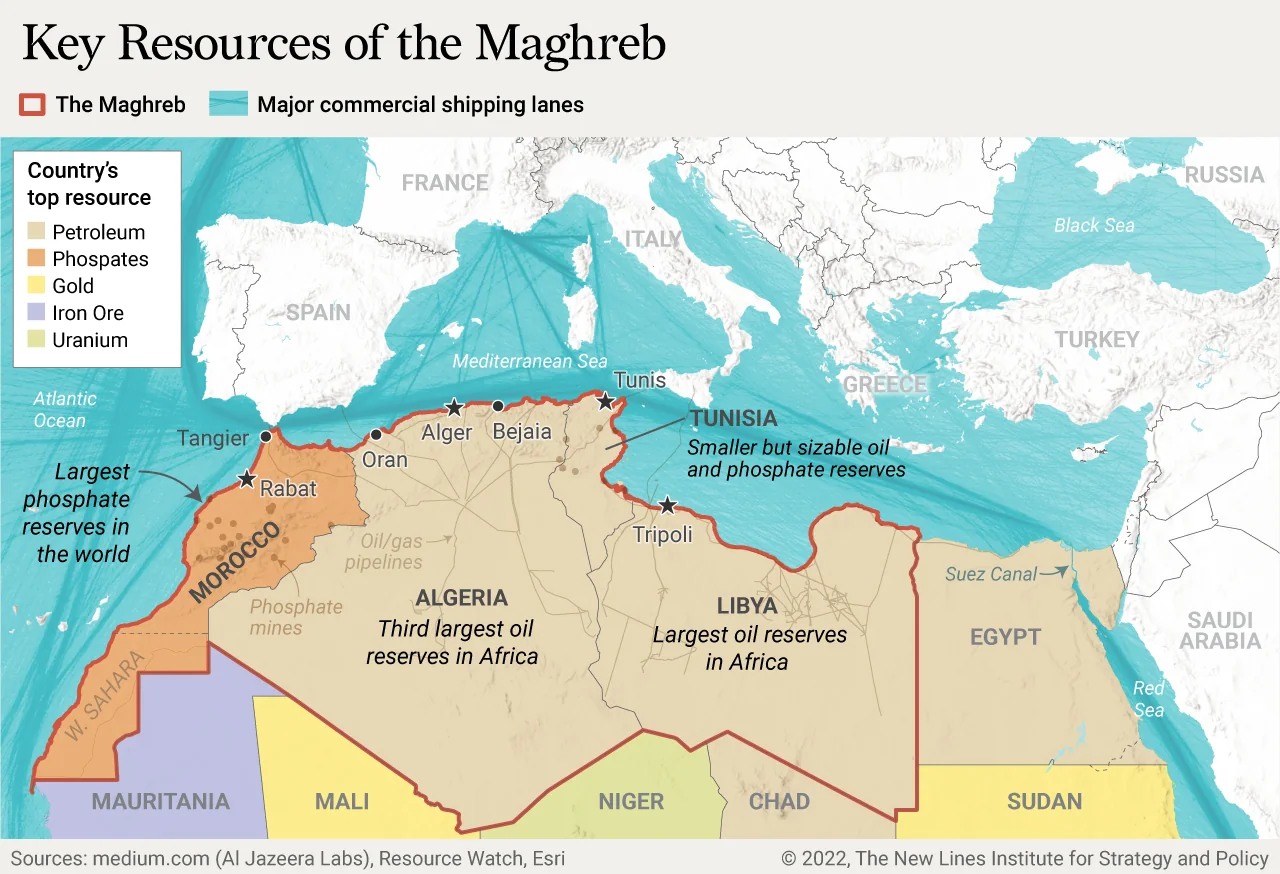

The Maghreb extends from the Atlantic through the Mediterranean to the core of the Middle East, covering territory vital to U.S. national security. The region is rich in energy resources, and key trans-Mediterranean transportation routes connecting Europe and sub-Saharan Africa pass through Rabat, Tunis, and Algiers. An expanding Chinese presence in the region threatens to replace traditional alliances with the United States and Europe, not only through trade but also through growing defense and security cooperation. Meanwhile, Russia has renewed its military, economic, and diplomatic engagement in the region, including through weapons purchases and on-the-ground military support. While Russian military capabilities in the region are potentially overstated, they reflect Moscow’s geostrategic aims in Africa.

Libya and Algeria both have expansive southern territories that are linked to the Sahel, a largely ungoverned region critical for combatting violent extremism. The lack of stability in Libya has influenced smuggling and extremist activity, which also thrives on weak governance in Mali, Niger, Chad, and Sudan. This activity has spilled over into Tunisia and Algeria, with porous borders contributing to attacks perpetrated by extremist groups, including at major tourist destinations. From the perspective of European allies, furthering stability in the Maghreb will help secure energy sources, reduce criminality at Europe’s southern periphery, and combat illegal migration.

Despite its strategic importance, the Maghreb has historically drawn limited interest from the United States, and its relations with the Gulf countries often work against its goal of stability and democracy in the Maghreb. In particular, close alliances with Saudi Arabia and the UAE have translated into support for Gulf interventions in Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya that undermine these countries’ efforts to develop strong democracies or respond to the demands of their populations.

Gulf States’ Influence in the Maghreb

Historically, ties between the Arab Gulf and North Africa have not been particularly strong. In recent years, however, driven by a competition between blocs of Middle Eastern states for regional influence, the countries of North Africa have become a hot spot for Gulf intervention. Though strategies and alignments among Gulf actors have shifted over the past decade, with military interventions and intense rivalries transforming into tentative diplomatic engagement, the Maghreb countries remain largely unable to prevent such interference from adversely affecting their democratic development.

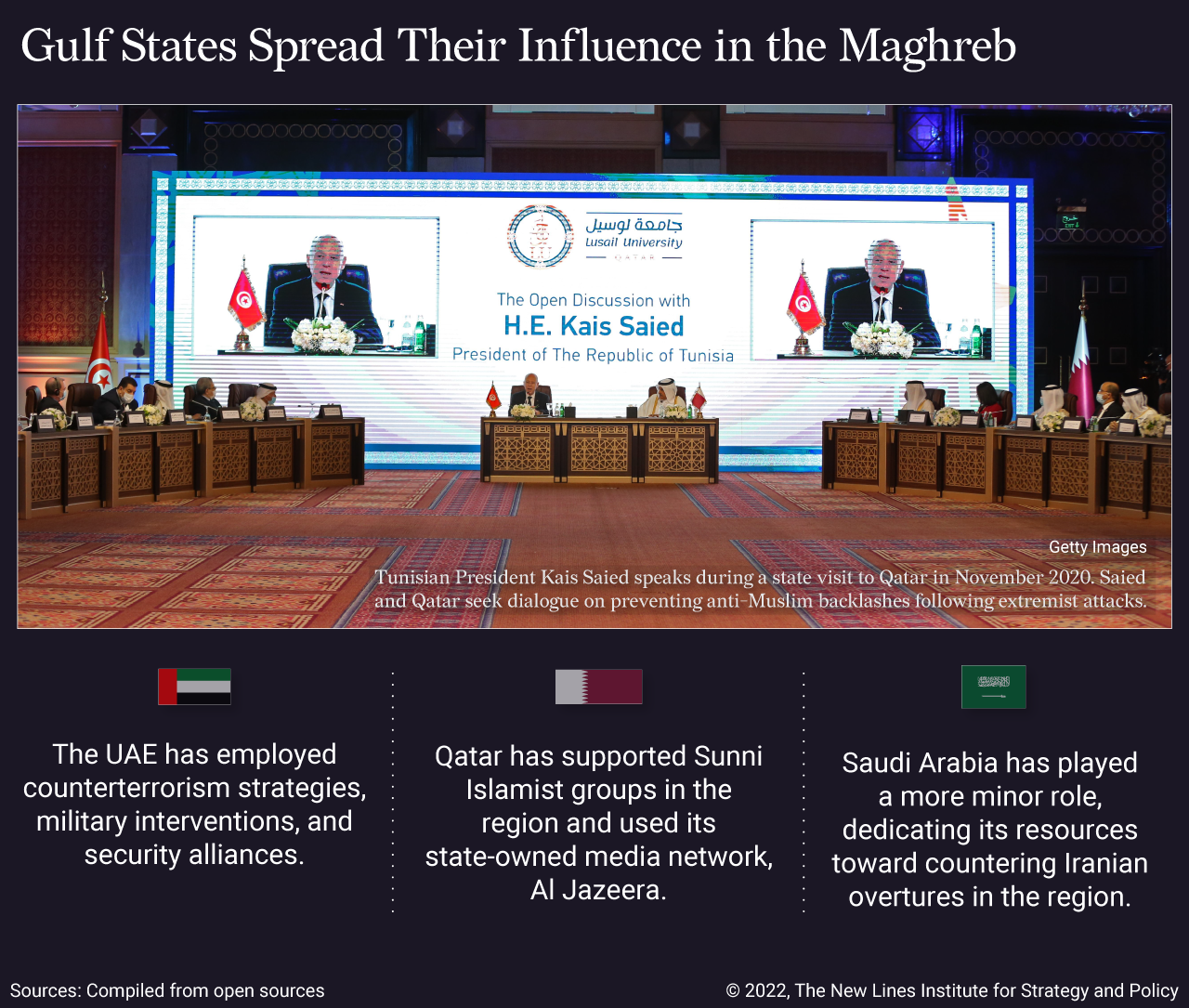

Gulf countries recognize the centrality of the Maghreb in achieving their strategic aims. Both Qatar and the UAE have sought to diversify their security alliances in order to reduce dependence on the United States and to spread their influence throughout the Middle East and North Africa. While the UAE has primarily sought to diversify its economy and build up its military, Qatar has tried to promote itself as an alternative voice in the Middle East, using its wealth to fund the highly influential Al Jazeera network and build a distinct Qatari identity. Saudi Arabia has been less active in the Maghreb recently, preferring to dedicate more resources to countering Iranian influence. As other regional heavyweights such as Turkey expand their activity in the Maghreb – including by backing allied Islamist and non-Islamist political forces – the Gulf countries have shaped their economic and security engagements in the Maghreb accordingly.

The Arab Spring offered an opportunity for Qatar and the UAE to pursue their ambitions. As previously repressed Islamist opposition movements began winning post-uprising elections, the UAE, whose rulers felt threatened by this sweep of anti-authoritarian strength, shifted to a muscular foreign policy involving arms sales, building up its military, and interventions in armed conflicts. Relying on its close ties with Washington and some European capitals, Abu Dhabi justified this by claiming a need to protect heavy-handed anti-Islamist regimes from terrorism.

Qatar, by contrast, saw the uprisings as a chance to demonstrate its credentials as a source of alternative identities for the Middle East. Given its longstanding ties with several Islamist opposition movements from Egypt, Libya, and elsewhere, Doha chose to support Sunni Islamists, particularly the Muslim Brotherhood, in their quest for access to power. This has frequently put it at odds with the Emirates and Saudi Arabia – a rivalry that has played out in the countries of the Maghreb.

Morocco, Algeria, and the Western Sahara Conflict

Morocco has historically enjoyed the strongest and most consistent ties with the conservative Gulf monarchies, particularly with Saudi Arabia and the UAE. The common monarchical regime structure, family ties, and the triangle of common alliance with the U.S., which supported Morocco’s claim to the Western Sahara, have all contributed to this closeness.

When the Arab Spring reached Morocco, the wealthy Gulf countries pledged assistance so that they would later be able to call on political favors, such as support for the Saudi-led escapade in Yemen. This was part of a long-standing pattern of Gulf economic interventions in the Maghreb, including loans, aid packages, and foreign direct investment.

Morocco has sought for the most part to tread carefully with Gulf aid. The UAE had built up significant investments there even before 2011, concentrated in real estate, tourism, infrastructure, and construction. In recent years, the balance across Gulf donors and investors in Morocco has shifted, with Qatari investments rising as Saudi investments have declined. This has roughly coincided with the dominance of the Islamist Justice and Development Party (PJD), until the most recent elections in 2021. This increase of Qatari influence was perhaps most clearly reflected when in 2017 Morocco took a neutral position vis-à-vis the blockade by the UAE and Saudi Arabia against Qatar and even sent Doha food shipments by air.

In contrast to Morocco, Algeria has never had warm relations with the conservative Gulf monarchies. Instead, Algiers has traditionally promoted a fierce policy of non-alignment, limiting its ties with Riyadh, Abu Dhabi, and Doha.

Attempts by Gulf Cooperation Council countries to bring Maghrebi countries into their spheres of influence have been facilitated by the long-standing rivalry between Algeria and Morocco over the status of the Western Sahara. In August 2020, the U.S. helped broker the Abraham Accords, which normalized relations between the UAE and Israel. A few months later, Morocco normalized relations with Israel, after which the U.S. recognized Moroccan sovereignty over the Western Sahara. This reinforced the observation that the monarchy continues to try to balance relations between Qatar on the one hand and the Saudi/Emirati camp – defined by alignment with the U.S. and increasing opposition to Iran rather than Israel – on the other.

In late 2021, Algeria cut diplomatic ties with Morocco, accusing its neighbor of “hostile actions” including failing on its bilateral commitments regarding the Western Sahara. The Gulf states have exploited this rivalry to build up their own investments, and they continue to watch the internal politics of both countries closely, particularly as unrest and economic paralysis in Algeria persist. Dubai Ports World – a key Emirati tool for spreading economic and political power – in 2008 began operating the Ports of Algiers and the eastern port of Djen Djen. Algeria, which traditionally buys large amounts of weapons from Russia, has also made major military equipment purchases from the UAE. Diplomatic relations have also improved between Algeria and the Gulf states, reflected in a series of high-level visits and discussions over investments and trade in 2020 and 2021. This is likely driven by Algeria’s growing concerns over regional security and economic stability.

Political Competition in Tunisia

Before the fall of former President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali in 2011, Tunisian relations with the conservative Gulf monarchies were cordial but not deep. This changed when the first post-Ben Ali elections in October 2011 brought to power a “Troika” government led by the previously banned Islamist party Ennahda. Tunisia’s relations with the UAE soon cooled to such an extent that in 2013 the Emirati ambassador was recalled from Tunis. At the same time, based on its favorable stance on political Islam, Qatar’s relations with Tunis deepened through the expansion of investments, loans, construction deals, foreign and humanitarian assistance, vocational training, and military cooperation.

In 2014 a new Tunisian government was elected, led by Beji Caid Essebsi and his secularist Nida Tounis party. Though Caid Essebsi was initially courted by the UAE, which hoped to persuade him to reduce the power of his Islamist opponents, he tried to retain a certain distance. Then, in 2021, President Kais Saied, who had been elected in 2019 following the death of Caid Essebsi, froze parliament and dismissed the prime minister, which many interpreted partly as a move against political Islam. Notably, the government raided the office of the Qatari news outlet al Jazeera in Tunis the day after Saied’s power grab, and shortly thereafter Saudi Arabia pledged assistance to support Tunisia’s COVID-19 crisis. In addition to once again swinging the pendulum toward the Saudi-Emirati axis within the divided Gulf Cooperation Council, Saied’s power grab sent ripples of concern among Islamists across the rest of North Africa, along with concerns about general stability in the region.

The UAE, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia have all sought since 2011 to subtly exert their influence in Tunisia. From the early weeks following the 2011 uprisings, these countries mobilized their media networks to launch campaigns that have contributed to deepening polarization between supporters and opponents of political Islam. Tunisian media outlets have benefited from poorly regulated external funding from Qatar and the UAE to spread false messaging, undermining Tunisians’ newly-won media freedom. These countries have also used their media networks to woo parties and politicians ahead of elections, promising investments and other forms of support. As in Libya, analysts identified evidence of coordinated campaigns among accounts based in Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and the UAE pushing an anti-Islamist narrative in the days following Saed’s power grab, creating the appearance of popular support for his move. Such actions have contributed to concerns about foreign meddling, weakening Tunisians’ trust in democracy.

After the fall of the Ben Ali government in Tunisia, some inside the country worried that Gulf actors such as Qatar were taking advantage of the chaos to fund charity associations, preachers, and other activities that would promote the brand of Islam they supported. Although funding for this form of intervention is particularly hard to track and, unlike with military intervention, its effects are not as concrete, many attribute it to the rise of extremism in Tunisia. Given the harshly restricted environment Islamists had faced under Ben Ali, the claim likely has some merit.

War and Diplomacy in Libya

When the Arab Spring uprisings broke out in February 2011 in Libya, both Qatar and the UAE saw it in their interest to support the overthrow of Moammar Gadhafi. Unconditional and bilateral financial aid as well as equipment, fighters, and training from both countries immediately began flowing to anti-Gadhafi rebel groups, along with enthusiastic support for the U.N. Security Council Resolution authorizing a no-fly zone over Libya. Qatar and the Emirates supported different rebel groups, however, based on existing ties, which eventually led them to back opposing Libyan factions and laid the seeds for their later rivalry, which emerged in the summer of 2014.

Gulf support for individual Libyans has also appeared to help fuel the conflict. For instance, Qatari support for Abdelhakim Bilhaj – a former member of the opposition Libya Islamic Fighting Group – may have contributed to Bilhaj’s defeat in his bid for a seat on the General National Congress in 2012, with some accusing him of being an agent of Qatar. Former Libyan ambassador to the UAE Aref al-Nayed used his ties with Abu Dhabi to launch his own political career, aspiring to become the president of Libya following the elections initially planned for December 2021. The Emirates also caused a scandal by hiring U.N. Special Envoy Bernardino León as director general of its diplomatic academy after he completed his term as the main mediator between the two conflicting sides in 2015. This raised legitimate questions regarding Leon’s behavior as an impartial arbiter, undermining the U.N.’s authority.

Over time Qatar’s and the UAE’s approaches to military involvement in the Libyan conflict evolved. From approximately 2013, Qatari involvement scaled back, the result of backlash from other countries in the region, its own leadership change, and a growing awareness of its limited capacity to realize the kind of influence it had once envisaged despite its alliance with Turkey. Meanwhile, Emirati involvement grew, particularly as tensions rose among coalitions identifying with or opposing political Islam. The UAE’s intervention in the Libya conflict evolved into a multi-pronged strategy parallel to the one in Yemen, involving the use of proxy actors, a strong alliance with Egypt (necessary for its powerful military), working through tribes and expatriates (such as Nayed), and potential counterterrorism engagement.

Though neither Qatar’s nor the UAE’s goals have changed in the Maghreb, since 2011 both have transformed their engagements into more pragmatic diplomacy. For Qatar, this took the form of direct partnership with the internationally recognized Government of National Accord (GNA) based in Tripoli. The GNA by 2019 was heavily supported by Turkey – another regional heavyweight with geostrategic and economic ambitions in Libya and the broader Maghreb.

Following the departure in early 2021 of U.S. President Donald Trump – with whom the UAE had been very close – and the defeat of the anti-GNA coalition in Libya, the UAE began deepening its diplomacy across the region, including with its once-rival in Libya, Turkey. While kinetic conflict in Libya has abated for the moment, its political process has also collapsed, and many perceive these shifting regional dynamics as unstable.

Conclusions

Although Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the Emirates’ strategies for advancing their agendas in the Maghreb have changed since 2011, their goals have not. They aim to advance their regional influence while protecting their own regimes. The forms and levels of Gulf intervention in the Maghreb vary across time, but they are always in the interest of the Gulf states, not the Maghreb. While interventions may bring welcome downstream effects – for example, job creation through heavy Gulf investments in key sectors – these investments come with political costs that undermine democratic development by discouraging attempts at political negotiation and compromise.

The United States and its European allies should ensure that liberal values support those forces that are threatened by interventions from the Gulf. For example, the Biden administration should exercise vigilance on the ground as Tunisia continues to experience political and economic tumult in order to ensure its policy is not dictated by the will of its Gulf allies. The U.S. can also continue to support the regulation of social media platforms including Facebook and Twitter so they are not used by foreign countries to propagate disinformation campaigns that in turn perpetuate conflict.

Karim Mezran is Director of the North African Initiative and Resident Senior fellow at the Rafik Hariri Center at the Atlantic Council.

Sabina Henneberg is the author of Managing Transition: The First Post-Uprising Phase in Tunisia and Libya.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not an official policy or position of the New Lines Institute.