Tucked in a 100-page document that a dissident group within the Islamic State released in 2018 was an incredible story about a miracle. The biographical document was meant to chronicle the life of an Iraqi jihadist from being a young man with an ambition to raise pigeons to becoming one of the most influential ISIS leaders.

The biography of Abu Ali al-Anbari, ISIS’s former deputy who was killed in 2018, had clearly been meant to establish the person’s religious and tribal credentials, in case the leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi was to be killed. It speaks about how the family was not of Turkish origins as it was widely known, that he grew up in a devout family, and that his father had predicted he could one day become the leader of the Muslim community, much like al-Baghdadi. The prediction, according to the biography, came after a leaf fell from a tree into a copy of the Quran al-Anbari was reading, and it somehow had the word “Allah” written on it. His father told him he had a bright future ahead of him.

That document has a renewed relevance. A central claim in the document involves the ethnic origins of the family to whom the current ISIS leader belongs. If he is of Turkish origin, then his claim to be of the Arab tribe of Quraysh is false, and thus his claims to be a caliph are illegitimate. ISIS insists he belongs to the tribe of Prophet Mohammed, and that only one of those could claim to be the legitimate leader of the Muslim community, as told by Islamic traditions some extremists cite.

This question about the true origins of the current leader of ISIS has led the United Nations to conclude in a report that Hajji Abdullah was merely a placeholder caliph until his organization could find an Arab with the right tribal and religious qualifications. On the other hand, both ISIS and the tribe insist the tribe is in fact Arab, even if it was “Turkified” in the way they integrated, in terms of language and traditions, with the Turkomen in northern Iraq with whom they mingled for centuries.

Sources in Iraq have now revealed biographical details never told before about the current leader of ISIS, which should put an end to speculations in media and policy circles about his tribal origins, but also shed light into the leadership core of this shadowy organization and its worldviews.

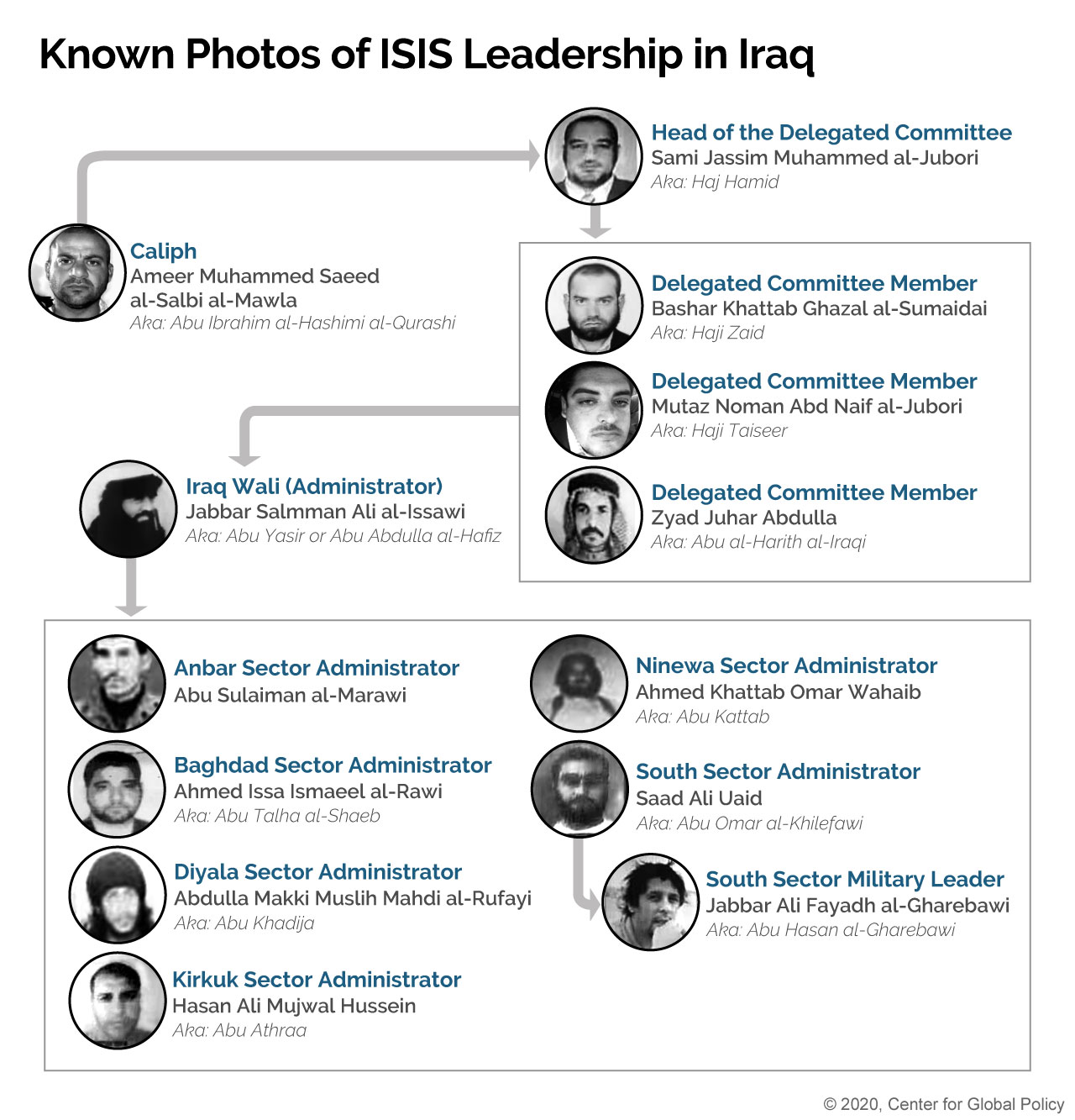

Amir Muhammad Sa’id Abd-al-Rahman al-Mawla, which is the real name of the person identified by ISIS only as Abu Ibrahim al-Hashemi al-Qurashi, was born in 1976 in a village near Mosul. The village, known as al-Mahalabiyah, is dominated by the Turkomen ethnic minority in Iraq, which is why authorities in Iraq and the United States were convinced the group lied about the ethnic origins of its leader — an aspect they hoped they could exploit to exacerbate existing disputes within the organization, according to sources in Baghdad familiar with those discussions.

He is the second leader after al-Baghdadi, who was killed in a U.S. raid in northern Syria last October, to have formal religious training. He holds a bachelor’s degree in Islamic studies from a shariah college at the University of Mosul. His father was also an imam at a mosque in Mosul, and the current leader developed a nickname as the teacher or master, for his religious knowledge. Al-Mawla even served as a judge in the Islamic State of Iraq (known at the time as al Qaeda in Iraq) before he was captured and jailed by the United States in southern Iraq in Camp Bucca in 2008.

He was released the following year. Iraqi sources say he was released after he denied that he pledged allegiance to al Qaeda and after informing on all his fellow jihadists, as detailed in documents of the U.S. authorities’ interrogation of the current leader when he was in jail. But well-placed Iraqi sources cast doubt on what they describe as “weak” claims about the group’s current leadership that could only help the group in the long-run. This pushback against such misleading details matters: the Iraqi sources argued that false information, meant to mock the organization, sometimes ended up helping the organization when those claims would later be debunked, and could cloud our understanding of dynamics within the group. Examples of such botched counter-propaganda include misidentifying certain leaders as former Baathists or that the current leader lied about his Arab origins.

The Iraqi sources say al-Mawla had been a trusted aide of al-Baghdadi before the latter was killed, which would not have been the case if al-Mawla had informed on his fellow jihadists. Such groups have developed a system of surrounding their leaders with reliable and trusted individuals trained to withhold critical information. Another grounds for the pushback against the claim is that the same claim was made by authorities in Baghdad about another top ISIS leader, namely Abdul Nasser Qardash, a relative of the current leader. The claim about Qardash was independently corroborated by a jihadist source in Syria, who said he had known Qardash when both were part of the anti-American insurgency in 2005. The jihadist source in Syria said that Qardash had told the United States all details he knew about al Qaeda’s bases in Iraq. As a result, the leader of al Qaeda in Iraq at the time, the Jordanian Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, had instructed his group never to give Qardash a leadership position when he left prison, because he was a snitch.

Official and other sources offer another picture that authorities publicly draw of the new leadership of ISIS. Hajji Abdullah, the current ISIS leader, is part of a tight group within the organization, followers of al-Anbari, the former top ISIS leader whose father had predicted he could command the faithful. Up to his death, Anbari had been the longest-serving and highest-ranking cleric within ISIS. He had been associated with the insurgency against Saddam Hussain in the 1990s and early 2000s.

That faction, known as the Qaradish, have always played a key and outsized role within ISIS since its inception, even if the organization was publicly known as the child of one foreign jihadist from Jordan. Before the current leader, al-Anbari was the closest this faction came to taking over ISIS, and his biography was a preemptive attempt to justify his credentials. He was killed even before al-Baghdadi’s demise, but his disciple al-Mawla made it.

Hassan Hassan is the Director of the Human Security Unit at the Newlines Institute. He is also the Founder and Editor-in-Chief of Newlines Magazine, an initiative of the Newlines Institute. His research focuses on militant movements, nonviolent extremism, and geopolitics in the Middle East. Hassan has also served as a contributing writer at The Atlantic, The Guardian, and Foreign Policy.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of the Newlines Institute.