Operation Claw-Sword, the latest iteration of the ongoing Turkish military effort targeting Kurdish-led militant groups, has increased uncertainty in security efforts in northeastern Syria by targeting key infrastructural and command nodes, blurring existing front lines, and complicating priorities among local stakeholders. Although a Turkish military incursion does not appear imminent, intense shelling and airstrikes conducted by Turkish forces across the region have once again highlighted the precarious nature of the counter-Islamic State (C-ISIS) mission in northeastern Syria, which relies on the tenuous and oft-violated cease-fire between the U.S.-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and NATO member Turkey to maintain regional stability.

The Kurdish-led SDF was compelled to adjust its force posture to defend against the barrage of Turkish airstrikes and prepare for a potential ground offensive. SDF officials temporarily paused operations targeting the Islamic State and reassigned forces that had been conducting joint patrols, securing facilities for Islamic State detainees and internally displaced persons, and performing clearance operations to bolster defensive efforts along the front line with Turkey. These developments have prompted concerns that the shift in focus by the SDF could give the Islamic State the opportunity to resurge and reconstitute in northeastern Syria. Turkey’s targeting of civilian infrastructure as part of Operation Claw-Sword, which commenced in late November, has also jeopardized the stability of regional human security efforts. The situation illuminates a series of blind spots in partner capacity and strategy, raising important questions about the U.S.-led coalition’s long-term sustainability in the face of cyclical security challenges from Turkey.

As the United States seeks to encourage a return to a 2019 cease-fire deal that ended Turkey’s “Operation Peace Spring” incursion into northeastern Syria, it must acknowledge two realities. First, Turkish territorial encroachment in northeastern Syria will continue to undermine the C-ISIS mission for the foreseeable future. Turkey has established a routine pattern of escalation over the past year, with cycles of airstrikes and saber rattling that may not always lead to a major ground offensive but nonetheless impose disruptions to operations undertaken by the SDF and allied forces and even direct threats to personnel safety. Second, the SDF cannot undertake campaigns against both the Islamic State and Turkey simultaneously. The United States and its coalition partners must establish a long-term, sustainable military and political contingency strategy that pre-emptively disrupts anticipated Turkish escalatory cycles against the SDF.

Diluted SDF Capacity

The SDF has served as the primary partner for the U.S.-led coalition’s “by, with, and through” (BWT) approach in northeastern Syria. The Department of Defense has leaned on BWT as a mechanism to lighten the load of its forward operating presence in the Middle East writ large as the United States continues to pivot its focus toward competition with China and Russia. The United States has applied the BWT approach to its missions in Iraq and Syria in particular, employing smaller teams of U.S. forces and contractors to facilitate training, intelligence-sharing, and coordination with partner forces on the ground. However, Syria’s unresolved civil war has complicated the BWT approach.

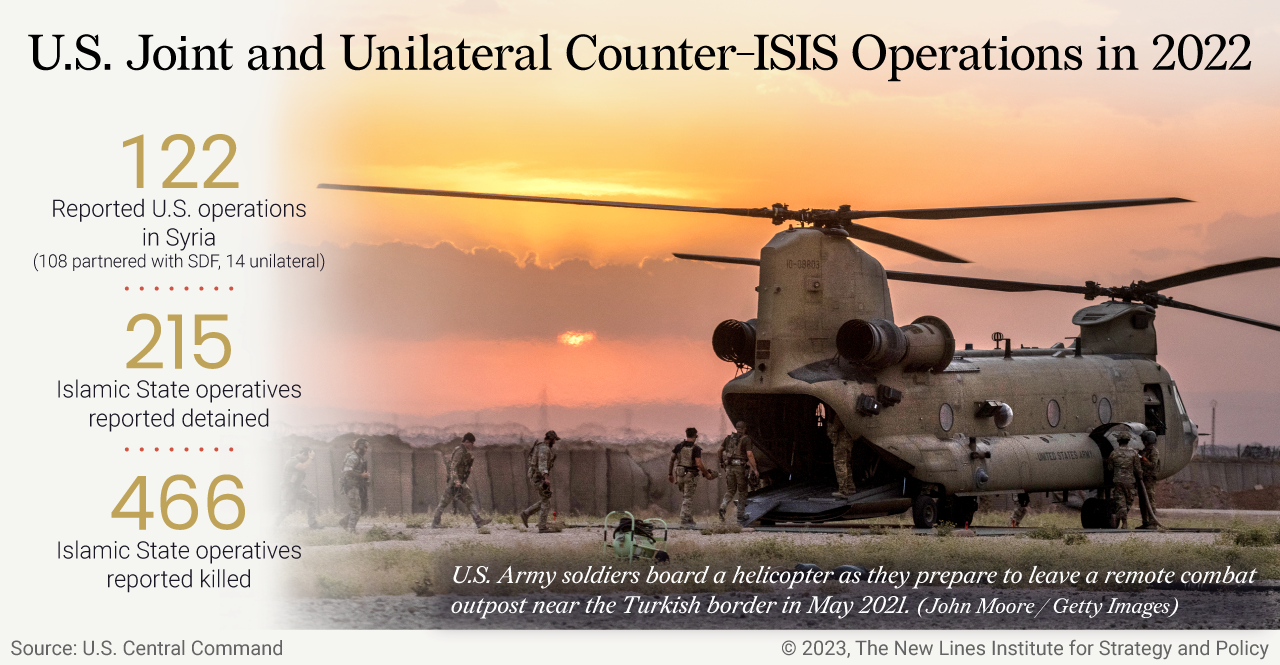

As the war’s uneasy stalemate has lingered, the United States has struggled to keep its allies on the same page concerning near-term goals, leading to friction over how to prioritize objectives including defeating the Islamic State and repatriating the over 5 million refugees currently living in neighboring states. Nowhere is this tension more obvious than in Syria’s northeast, where Turkey views the SDF as a greater security threat than the jihadist group itself. U.S. efforts to incorporate BWT in northeastern Syria have enshrined the SDF as its chief partner, seeking to build its operational capacity and incrementally offload security responsibilities to constrain threats such as the Islamic State. In efforts by the Combined Joint Task Force – Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR), to advise, assist, and enable these forces since 2015, the SDF has become a success story for capacity-building efforts — its forces have become “moderately capable” of conducting conventional and counterterrorism operations on their own according to reports by the Defense Department Office of Inspector General. Additionally, the SDF is building a network of internal security forces, commandos, and intelligence cadres that maintain over 24 detention centers and several camps for internally displaced people. The SDF’s command over planning, intelligence, perimeter security, and command and control enabled the United States to reduce its OIR budget and its footprint in northeastern Syria from 2,200 personnel to just 1,000 by 2019, without the consequence of a major Islamic State resurgence. In 2022 alone, the SDF was involved in over 100 partnered operations with the United States, resulting in 215 Islamic State operatives detained and 466 killed.

However, the SDF’s capacity and reliability as a partner force has become precarious in the face of Turkish encroachment, creating a vacuum in which the coalition could lose momentum against the Islamic State and other third-party actors. In the months preceding Operation Claw-Sword, a series of cross-border attacks and exchanges of indirect fire between Turkish forces and forces in SDF-held territory had begun to pull the SDF in different directions, forcing it to choose between resourcing for efforts to counter the Islamic State and defense against an anticipated Turkish incursion.

Turkish attacks have dealt a blow against the SDF’s officer and counterterrorism cadre — well-trained operatives upon whom the United States has relied for human intelligence and frequent C-ISIS raids. During the most recent round of escalation, Turkey and its proxies killed nearly 30 SDF fighters in attacks between Nov. 19 and 30, including eight members of the group’s elite commando units and two members of its Anti-Terror Units, which serve an outsized role in anti-Islamic State operations across Syria’s northeast, according to data collected by open-source investigator Alexander McKeever. Additionally, Turkish airstrikes killed Jiyan Tolhildan, a commander in the SDF’s special operation anti-terrorist task force. In July 2022, when Ankara was again threatening an imminent ground invasion of northeastern Syria, a Turkish drone strike killed a deputy commander of the SDF, along with at least two fellow fighters.

Constant Turkish bombardment restricts the SDF’s freedom of movement and forces its leaders to isolate themselves for their own safety, restricting the group’s ability to coordinate and share intelligence across the nearly one-third of Syrian territory under its control. In the long term, the whittling effect of these attacks reduces the group’s personnel and institutional knowledge and diminishes morale of conscripted fighters and volunteers who know that they are in Turkey’s crosshairs. In the latest quarterly congressional report on Operation Inherent Resolve, the DOD Office of Inspector General confirmed that the SDF’s force capacity was reduced by escalation with Turkey. The Department of Defense marked these developments with concern, warning that the Islamic State could exploit pauses in operations and diminished coalition presence to regenerate strength, particularly after a notable uptick in the severity and frequency of its attacks against SDF and coalition targets in the summer and early autumn.

Confronted with Turkish aggression, SDF forces have sought to balance internal security and the C-ISIS operations. On Nov. 29, personnel with the Kurdish internal security force Asayish in Deir ez-Zor confiscated a bulk of short-range antitank weapons, automatic rifles, and ammunition from a 10-person Islamic State cell, dismantling the group. In lieu of SDF clearance operations, Asayish officers guarding purpose-built and makeshift detention centers have had to manage attempted jailbreaks among Islamic State fighters. Two Turkish drone strikes on the al-Hol camp on Nov. 23 reportedly killed as many as eight U.S.-trained SDF fighters guarding the camp, which houses 50,000 IDPs, including family members of Islamic State fighters. The attack led several detainees to attempt to flee before guards made arrests, highlighting the fragile security situation, where Islamic State-aligned members regularly attempt breakouts and attack other residents.

Infrastructural Damage of Turkish Strikes

Turkey’s attacks not only target the SDF’s fighters but also hit key civilian infrastructure across northeastern Syria with the apparent goal of degrading the Autonomous Administration’s revenue streams and reducing its ability to deliver services to the region’s residents. A potential long-term Turkish goal may be to depopulate areas near its border with Syria to make room for future repatriation efforts. Since Operation Claw-Sword got underway in mid-November, Turkish strikes have hit a number of civilian sites across northeastern Syria, including a hospital, a marble factory, a grain silo, and two power stations. These attacks run parallel to Turkey’s longer-running efforts to restrict the flow of the Euphrates River into northeastern Syria, damaging crop yields, affecting livestock quality, and threatening civilians’ access to potable water. Taken in context, the pattern of strikes appears focused on laying the groundwork for a future invasion and squeezing the Autonomous Administration and degrading its ability to govern the region — a dynamic that reduces the SDF’s capacity to act as an effective partner force.

The Northeastern Syria NGO Forum documented at least 17 incidents of damage to civilian infrastructure between Nov. 20 and 25 alone, including strikes on oil and gas fields and electric power generation plants. Local news outlets reported strikes against multiple gas stations in Hasakeh on Nov. 23 that forced them to suspend service. An attack the same day near a power center in Derik/al-Malikiyah disrupted electricity access in the city. These attacks on northeastern Syria’s energy infrastructure have exacerbated the country’s already severe winter fuel shortage, as most residents rely on fuel tanks to heat their homes.

These attacks serve the additional purpose of deterring future economic investment in the region, degrading the Autonomous Administration’s ability to generate new revenue streams and attract outside businesses to rebuild infrastructure decimated by over a decade of war. A U.S. decision to lift certain economic sanctions on the country’s northeast in May has not resulted in any major new investment projects, in part because Turkey’s airstrikes make business look too risky. Over time, these attacks degrade the Autonomous Administration’s ability to pay salaries and repair infrastructure, weakening its prospects for recruitment and sustainable operations, destabilizing the region, and increasing the region’s vulnerability to an Islamic State resurgence.

Filling the Gap?

In response to the Turkish strikes, the U.S. Central Command paused all combined C-ISIS operations with the SDF from Nov. 23 through Dec. 2. Coalition forces conducted a handful of exercises, intelligence collection efforts, and clearance operations independent of its partner force to help fill the gap in capacity. Days after SDF Commander Mazloum Abdi’s announcement of halted C-ISIS operations, the coalition announced that the French carrier strike group attached to the mission stepped up air-defense, protection, and ground-force coordination with the OIR’s anti-Islamic State efforts under Operation Chammal. As Turkish forces continued strikes in the area, coalition forces conducted live-fire readiness exercises in al-Jawadiyah and operational rehearsal exercises with M777 Howitzer in Conoco on Dec. 2 and 6. Even days after joint U.S.-SDF operations resumed, the United States sought to fill the capacity gap, with CENTCOM authorizing a unilateral Delta Force helicopter raid on Dec. 11 that killed two notable Islamic State leaders.

Additionally, data obtained from open-source aircraft flight-tracking services indicated that the Royal Air Force has begun to alternate reconnaissance missions between Ukraine and the shared Iraqi/Syrian border, alluding to the equal priority of the missions. The mission included an RC-135W Rivet Joint strategic reconnaissance aircraft, which sends information to local and regional commanders on the movements of Islamic State fighters as determined by radio and cellular intercepts (among other signals-based methods). These RAF assets join typical U.S. Air Force deployments to the region, including air tankers, reconnaissance assets (both strategic- and tactical-level), and communications aircraft. These forces are bolstered, as needed, by U.S. combat assets from nearby bases in the Persian Gulf States. In addition to RC-135W/V flights, on at least one recent occasion, the presence of the RC-135U Combat Sent has been noted over Iraq. The Combat Sent is used to send adversary military information such as signals and digital data to theater- and national-level leadership.

However, these adjustments are not sufficient or sustainable for long-term efforts to maintain capacity and root out Islamic State presence in the region. While forces resumed joint training drills and patrols with the OIR after the multiday pause, sustained Turkish attacks over time continue to threaten full participation by the SDF and prioritization of C-ISIS efforts, undermining long-term coalition capacity and forcing the SDF to entertain closer relationships with U.S. adversaries in the region. With the pressure of Turkish attacks and in absence of U.S. intervention/arbitration, the SDF has explored engagement opportunities with other direct and third-party stakeholders in Syria, such as the Syrian regime and its backer, Russia. In an effort to defuse the latest crisis, SDF commander Mazloum Abdi met with the commander of the Russian forces in Syria, saying, “Russia is now standing in a neutral position between us and Turkey.”

As the SDF leans more heavily on Russia to avert Turkish incursions, Russia has pressured the SDF into cutting a deal with the Assad regime to formally give Damascus control over the group’s territory. This move would jeopardize Operation Inherent Resolve, as Assad has been clear that he views the United States as an occupying power and would seek to evict U.S. forces at the first opportunity. The prospects of a comprehensive deal between the SDF and Damascus remain slim, but they inch closer to agreement with each round of Turkish escalation, as the SDF requests air defense systems from Russia and accepts reinforcements from Damascus to shore up defensive positions along its front lines. Each round of escalation leaves the SDF more reliant on Russia’s security umbrella to secure its territory, making the group vulnerable to a coerced settlement with the Assad regime that would force an abrupt end to Operation Inherent Resolve.

Discerning a Pattern

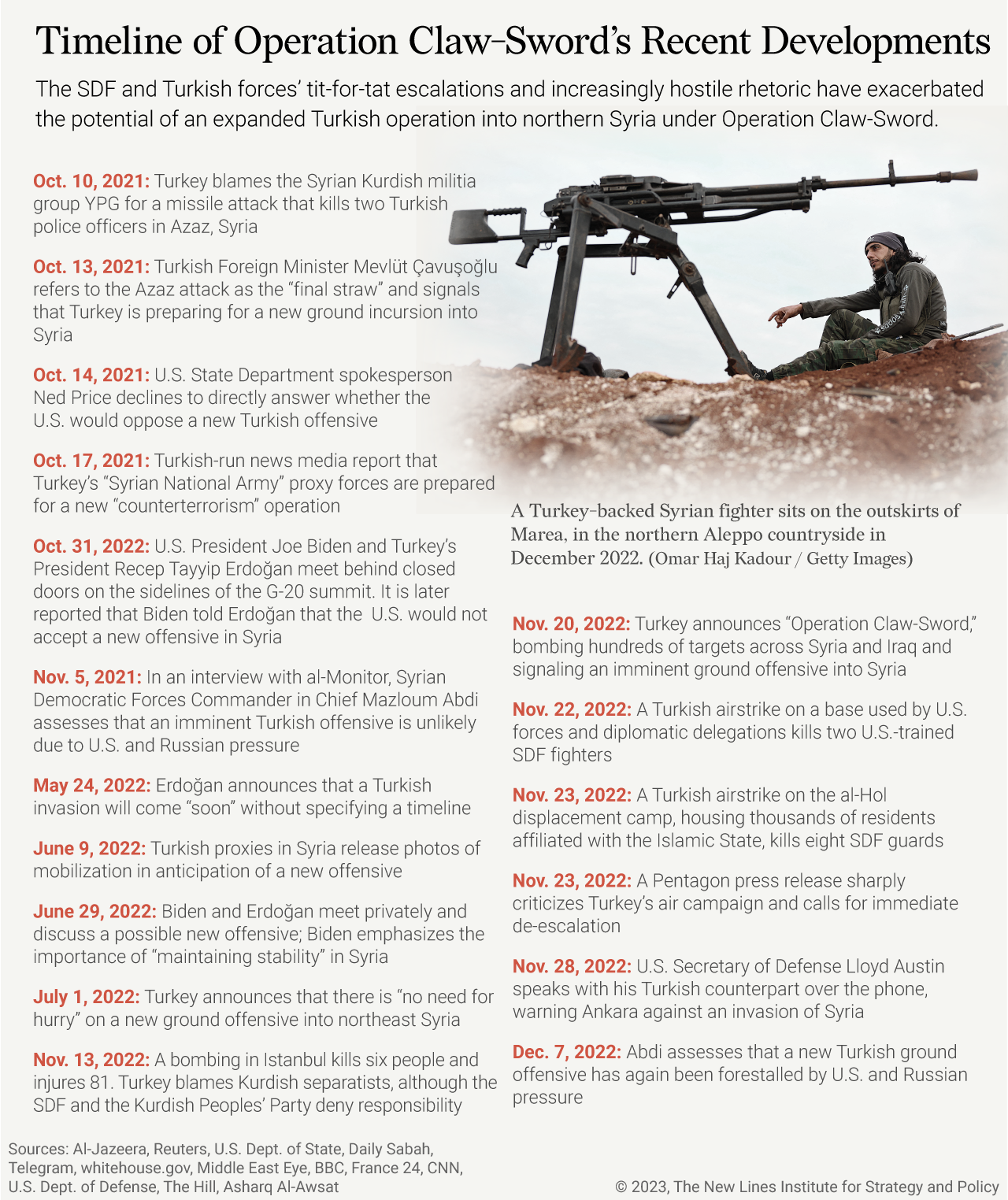

Ankara’s threats of an invasion are now a perennial feature of the Syrian conflict that, even on their own, pose a grave long-term threat to Operation Inherent Resolve and interoperability with the SDF.

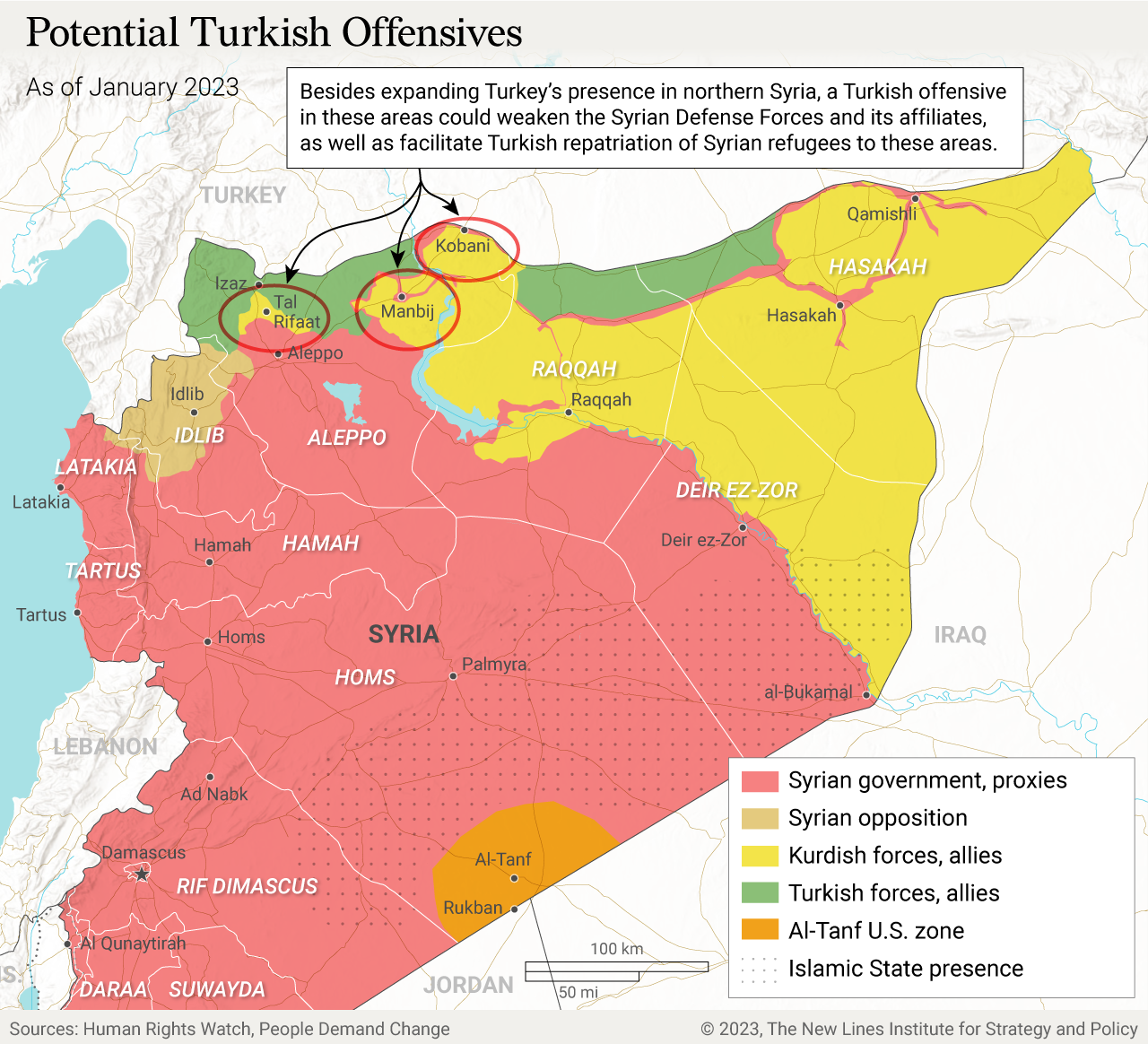

Since 2019, Turkey has sought to occupy a 30-kilometer (18.6-mile) “safe zone” across all of northern Syria, both to force the SDF away from Turkey’s borders and to create an area for repatriating Syrian refugees, whose presence in Turkey has become a liability for Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party ahead of spring 2023 elections. Russia and the U.S. have repeatedly applied pressure to warn Ankara against launching a major offensive to occupy new territory in northeastern Syria, but these Turkish cycles of rhetorical threats followed by intensified aerial bombardment and shelling continue.

Erdoğan has regularly signaled that a major new offensive against the SDF was imminent. In fall 2021, Erdoğan blamed the YPG – a Kurdish-led militia that forms the backbone of the SDF – for an attack that killed two Turkish police officers in Syria, calling it “the last straw” and signaling his intent to launch a new invasion into Syria to establish the 30-kilometer buffer zone across the country’s north. Unified opposition from Russia and the United States ultimately forced Erdoğan to put his plans on hold until May, when he once again threatened an imminent invasion of SDF-held territory. This threat was again placed on hold until Nov. 13, when a bombing in Istanbul bombing prompted yet another round of bluster from Ankara, which blamed the YPG for the attack.

These cycles of escalation follow a consistent pattern. First, alleged escalation by an SDF affiliate prompts fiery speeches by Erdoğan, who refers to the incident as the “final straw” and indicates that a new invasion is coming “soon.” Next, Turkey intensifies its air campaign, targeting SDF leaders, critical civilian infrastructure, and – in at least one case – a United Nations-funded school. Tit-for-tat escalation between SDF-aligned groups and Turkish proxies ensues, with both sides relying on indiscriminate shelling that kills civilians and destroys homes and schools. As the threat of an invasion grows, the United States and Russia both pressure Turkey to deescalate. Faced with unified opposition from the two most well-equipped outside powers in the country, Ankara then puts the new offensive on the back burner – never officially calling it off but stating that there is “no need for hurry.”

A Better Strategy

Even without a new invasion and signaled targeting of areas outside the coalition operational scope like Manbij and Tal Rifaat, this cycle of violence degrades the SDF over time in ways that threaten the C-ISIS mission and presents a widened power vacuum in the region. Whether or not Ankara maintains the tempo of its air attacks across northeastern Syria, escalates with a ground offensive, or opts for de-escalation, the U.S. and coalition partners should discern repeated Turkish escalation through Operation Claw-Sword as a warning for the long-term viability of C-ISIS operations. The BTW strategy is a successful approach only when the United States’ partner forces are on stable footing; Turkey’s aggression knocks the SDF off balance. While the war in Ukraine and the importance of NATO make Turkey too vital to write off completely, adversarial interests in Syria has placed the United States at a crossroads, jeopardizing its BWT approach. As the United States continues to narrow the scope of operations in the Middle East with the goal of eventual withdrawal, it should prioritize capacity-building to preserve relative security in the region. Given the likelihood of future Turkish military campaigns in northeastern Syria, the United States and its partners should develop contingency plans for when the rug is pulled out from underneath top coalition partners.

Washington has occasionally demonstrated that it can deter Turkey from new Syrian offenses. But the near misses are themselves destabilizing, and Operation Inherent Resolve would be more sustainable if policymakers had a similarly robust playbook for averting the cycles of escalation and de-escalation that have become a fact of life for residents of northeastern Syria over the past year. This would require modest but sustained engagement across the U.S. government. First the State Department should adopt an accountability approach to escalatory acts that harm civilians and civilian infrastructure in northeastern Syria, clearly naming and shaming the attack’s perpetrators, rather than issuing broad calls for de-escalation that fail to explicitly identify the attacker. A more proactive and pointed response to individual attacks would make U.S. resolve and attention clearer to all parties involved. Second, the White House should work with Congress to develop a clear, actionable sanctions package in the event of a Turkish ground invasion and pre-emptively make the consequences of an incursion clear to Ankara for deterrence. Making the consequences of an invasion clear before Turkey begins its next round of escalation may give policymakers in Ankara pause.

Lastly, the Department of Defense should communicate quietly but emphatically with the SDF to caution the group against retaliating against Turkey, particularly with the use of indiscriminate shelling. In the latest round of escalation, SDF-held territory was used to launch rockets at a school in southern Turkey, killing at least two people. The United States should make it clear to its partners in Syria that these attacks are unacceptable, and continued U.S. funding and support for partner forces is contingent on their adhering to basic human rights norms, including refraining from the use of cross-border attacks into civilian areas.

This latest round of escalation demonstrates again the pivotal role the United States plays as a security guarantor in northeastern Syria — a role that has the capacity to de-escalate tensions between its Turkish and Kurdish counterparts. But when other actors perceive a lack of U.S. resolve, they calibrate their actions accordingly, creating escalatory and destabilizing cycles of violence that threaten to force a premature end to the C-ISIS mission. Fortunately for policymakers in Washington, a handful of moderate but proactive steps to signal continued U.S. attention to this file offer a promising long-term strategy that proactively curbs dangerous escalatory cycles.

Caroline Rose is a Portfolio Director at New Lines. Her commentary and work on geopolitics and Middle Eastern affairs have been featured in Foreign Policy, The Independent, Alhurra, Limes Magazine, and the Atlantic Council’s MENASource. She tweets at @CarolineRose8.

Aram Shabanian is an Open-Source Information Gathering (OSIG) Manager at New Lines. He focuses on researching and analyzing violent far-right groups in the US, as well as the Islamic State Group and associated movements. In late 2018 he was accepted to the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey, where he went on to earn an MA in Non-Proliferation and Terrorism Studies, graduating in 2021. He tweets on @ShabanianAram.

Calvin Wilder is an Analyst at the New Lines Institute. Prior to joining the New Lines Institute, Calvin was a Research Assistant at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy’s Program on Arab Politics. He previously worked as a Research Assistant on the Chicago Project for Security and Threats (CPOST)’s Arabic Propaganda Analysis Team, and he was a Boren Scholar in Amman, Jordan from 2019-2020, working as a research and translation intern at Syria Direct. He holds a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science from the University of Chicago. He tweets at @CalvinWilder.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of the New Lines Institute.