Last month’s hostage-taking situation in Colleyville, Texas, was the latest example of ideologically motivated violence directed at a house of worship. Jewish institutions are especially at risk of attack by far-right actors, violent Islamists, and others, though recent history indicates there is no shortage of violence directed at Muslim, Sikh, and Black Christian houses of worship, as well as a variety of nonprofits. Data from the FBI and other sources suggest such attacks are a rising trend in the United States. A National Terrorism Advisory System Bulletin issued by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security on Feb. 7, 2022, further highlights the elevated threat environment posed to nonprofits like faith-based organizations and institutions of higher education.

In the wake of incidents like these, policymakers and community figures have called for increased funding to enhance security at nonprofits and houses of worship, including a federal program called the Non-Profit Security Grant Program (NSGP). While the NSGP can play a significant role in preventing and mitigating ideologically motivated violence, changes to the program are needed to realize its full potential. These include: more funding for its operations and management, enhancing accessibility to under-served communities, rethinking the kinds of security countermeasures it prioritizes, and providing more access to data to better inform policymaking and future program design.

What is the NSGP?

The NSGP was created by legislation enacted in 2004 and distributed its first grants in Fiscal Year (FY) 2005. The idea for the NSGP came in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks and was first proposed by the Jewish Federations of North America on Dec. 11, 2001. On paper, the remit of the program covers both faith-based and non-faith-based (hereafter “secular”) nonprofit entities, although as discussed later in this analysis, the reality is much more complicated.

Regardless of these complications, demand for the program’s funds has been extremely high. During last fiscal year’s grant cycle, FEMA received and reviewed 3,361 applications. Of these, 1,532 (45.6%) were approved.

The NSGP is one of eight federal non-disaster grant programs under FEMA, which seeks to advance its National Preparedness Goal (“The Goal”) of addressing “the threats and hazards [both natural and man-made] that pose the greatest risk” to public safety and security. NSGP’s main function is to provide funding for physical security upgrades and other security-related enhancements to nonprofit entities determined to be at high risk of attack from terrorism and other ideologically motivated violence.

By design, the NSGP is a reimbursement program, covering nonprofit entities’ costs for four categories of goods and services after they have been purchased:

- Protection of “soft” targets and crowded places. Examples of activities under this category include strengthening access controls like better fencing, gates, and barriers, hiring private security guards, and installing closed circuit television equipment.

- Development of effective preparedness and response planning. Examples include hiring professionals to conduct security risk assessments and the development of security plans/protocols, emergency contingency plans, and evacuation/shelter in place plans.

- Training and enabling participation in awareness campaigns. This encompasses things like active shooter trainings, security training for employees, and public awareness/preparedness campaigns.

- Other exercises. This encompasses things such as response exercises designed to simulate and practice reactions to the aftermath of a disaster.

According to the most recent version (FY 2021) of the NSGP’s Notice Of Funding Opportunity, the first category “attracts the most concern.” The other three categories are described in the notice as “second-tier priorities that help recipients implement a comprehensive approach to securing communities.” With the exception of private security guards, the first category otherwise emphasizes physical security measures to “harden” a target.

This is an important feature of the NSGP to note. Physical measures prevented loss of life at places like an African American church in Jeffersontown, Kentucky, and a synagogue in Halle, Germany. However, it did not appear to prevent the hostage-taking incident at Congregation Beth Israel in Colleyville, which was a recipient of NSGP funds in 2020. Instead, Rabbi Charlie Cytron-Walker credited the security training he received with helping to save himself and his fellow captive congregants. (It is unclear if Congregation Beth Israel had an opportunity to implement its intended security upgrades prior to the hostage-taking incident, which, according to NSGP data, was intended to “fund the purchase and installation of physical security enhancement equipment and contracted security personnel.” An armed guard was not present at the time of the incident.)

Program Structure and a Snapshot of its Application Process

Currently, the NSGP is divided into two geographic administrative areas that govern how prospective applicants apply for funding. The first is the NSGP-Urban Area (NSGP-UA) which provides funding for nonprofit organizations physically located within a FY 2021 designated Urban Area Security Initiative (UASI) urban area. (A UASI-designated urban area is any geographic location, as defined by FEMA, identified as a high-threat, high-population-density metropolitan statistical area.) The second is the NSGP-State (NSGP-S), which provides funding for nonprofit organizations physically located outside of UASI-UA areas. Areas designated as NSGP-UA or NSGP-S are continuously re-evaluated, and a particular designation can change before the start of a new fiscal year.

Whereas the NSGP-UA has been around since the NSGP became operational in FY 2005, the NSGP-S began operations in FY 2018 and was allocated a junior share of all annual NSGP funds during FY 2018-2020 period. However, in FY 2021, NSGP-UA and NSGP-S were each allocated $90 million, for a total of $180 million.

Technically, state-level agencies called State Administrative Agencies (SAAs) are the ones applying for the NSGP grants. However, they are applying directly for the funds on behalf of the nonprofits seeking the grants. When FEMA and the Department of Homeland Security review the applications sent by SAAs and decides which ones to accept, the money goes to the SAAs, which then distribute the funds to the approved nonprofits.

The application process for nonprofit entities is time-consuming. Applicants are explicitly encouraged by FEMA and SAAs to begin their paperwork at least several weeks before the deadline due to the number of steps and level of detail involved in completing the process. A quick description of its time-consuming and detail-demanding nature can be illustrated by a brief overview of what a satisfactory application looks like:

Preliminary Analysis of NSGP Sub-Awards

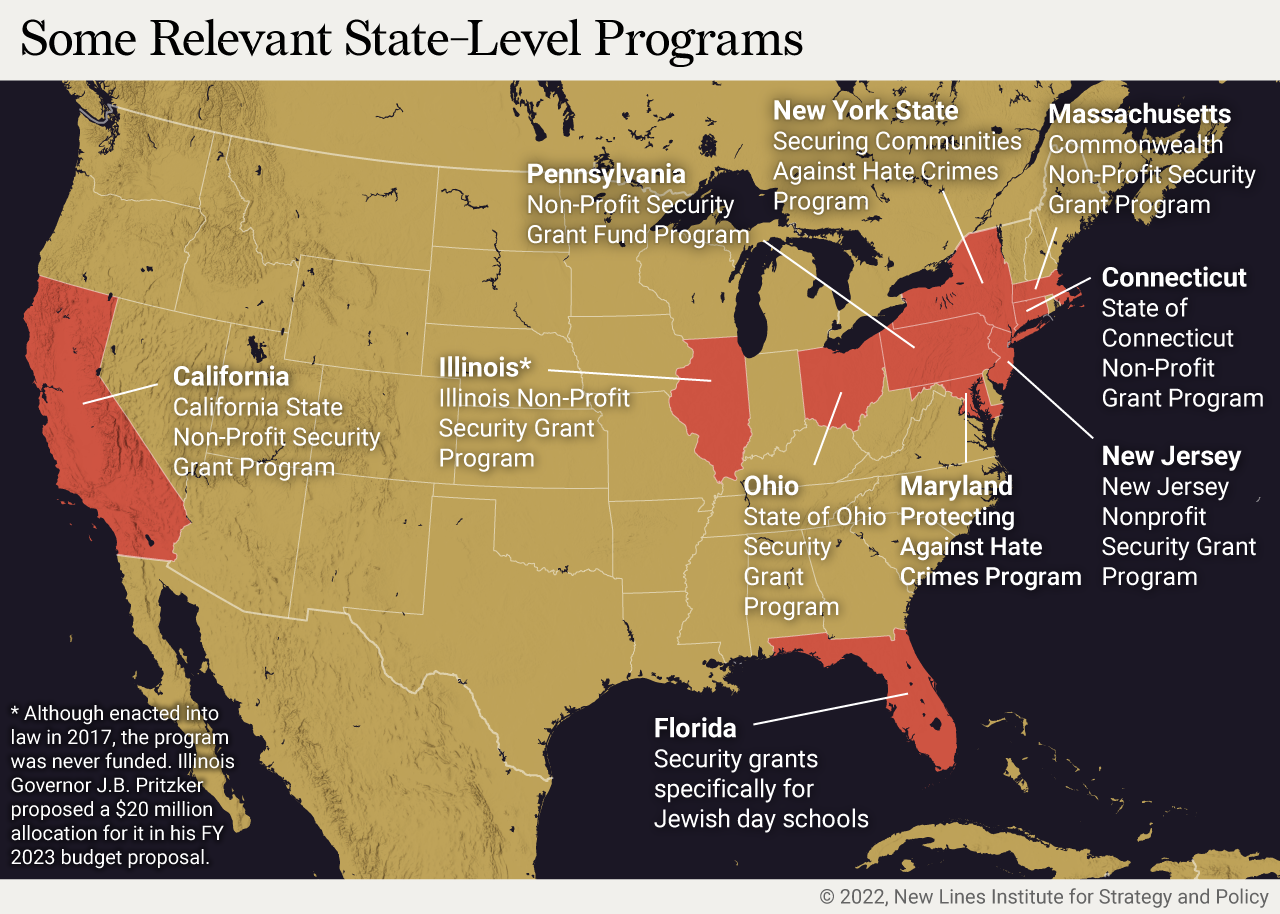

The data comes with a couple of caveats. First, in the past several years, state governments in New York, Connecticut, Florida, and elsewhere have established or significantly expanded their own versions of the NSGP. The data used for the present analysis focuses only on the federal NSGP, which these state versions are largely modeled after.

Second, to create a dataset for this analysis, the author was able to procure data from FY 2011 through May 2021 via the government contract/grant data clearinghouse USAspending.gov. This means that several years of historic data are not included in this dataset. A 2021 factsheet provided by the Union of Orthodox Jewish Congregations of America identified a total of $599 million apportioned between FY 2004 and FY 2021. The dataset in this analysis covers approximately $239 million, or about 48%, of all NSGP funds given to 41 U.S. states and the District of Columbia since FY 2011. Therefore, any interpretation and presentation of the data in this publication should be understood as a wide panoramic snapshot, not an exhaustive compilation of NSGP data. Nevertheless, although imperfect, to the author’s knowledge this represents the most systematic attempt to document and analyze the high-demand but understudied federal safety and security program to date.

The dataset, an extension of an earlier analysis of NSGP data conducted by the author, contains information on approximately 2,809 NSGP sub-awards given from FY 2011 to May 15, 2021, totaling $239,007,642.19. The average sub-award grant is $85,032.63, while the median sub-award size is $75,000 and most common sub-award size (mode) is $75,000.

Out of the overarching total documented in the dataset, secular sub-awardees have received $7,779,180.00 (~3.3%) across 96 sub-grants (~3.4%) of the total sub-awards given. By contrast, faith-based sub-awardees have received $231,228,462.19 (~96.7%) of all NSGP funds across 2,708 sub-grants (~95.7%) of the total sub-awards identified here.

For secular organizations, our findings are as follows:

- Medical institutions received 36 unique sub-grants (~1.2% of program-wide total) for a total of $2,519,263.00, or approximately 1% of all NSGP funds in the dataset. The average sub-award grant is $69,979.53, while both the median and mode sub-grant sizes are $71,250.

- Higher education institutions (any institutions of tertiary education without an official religious affiliation) received 11 unique (~0.3% of program-wide total) sub-grants worth $805,636.00, or 0.3% of all NSGP funds in the dataset. The average sub-award grant is $73,239.64, while both the median and mode sub-grant sizes are $75,000.

- “Other” (secular) institutions received 52 unique sub-grants (~1.8% of program-wide total) totaling of $4,234,857.00, across or approximately 2% of all NSGP funds in the dataset. The average sub-award grant is $81,439.56, the median sub-award size is $95,750, and the most common sub-award given is $100,000.

- Foreign entities received two unique sub-grants worth $244,424 (a negligible percent of program-wide total) or 0.1% of all NSGP funds identified in the dataset. One entity has an address listed in China and was given a $94,424 sub-award for activities to be performed in Virginia. The other entity has an address listed in Israel and was given a $150,000 sub-award for activities to be performed in Washington state.

A Look at the Distribution of Funds

Two features immediately stand out in this dataset. First is the asymmetry of sub-awards provided to faith-based versus secular entities. Second is the overall preponderance of Jewish institutional recipients. To longtime observers of the program, these two aspects of the data will likely come as no surprise and are consistent with prior reporting from news outlets like The Forward, Times of Israel, Jewish Telegraphic Agency, and Religion News Service. There are at least five reasons for these features.

First, as noted earlier, the main advocates pushing for the establishment of the NSGP were faith-based actors, thus providing them with a “historical” advantage of being aware of the program’s existence and how it generally operates.

Second, the NSGP’s design still largely favors faith-based entities, which qualify for the highest score boost during the DHS/FEMA review process. Despite changes to funding guideline wording in FY 2012 intended to clarify that certain types of secular entities can also qualify for the highest score boost category, the overwhelming majority of NSGP funding continues flowing to faith-based organizations.

The third factor is the strength of sub-grantees’ support networks to overcome challenges associated with participating in the NSGP. A 2019 report on security at houses of worship by the Department of Homeland Security’s Faith-Based Advisory Council highlighted aspects of the program’s design that effectively create disincentives for many organizations to participate in the program. It stated, “Significant segments of the faith-based communities are unaware of the grant process, or if they are aware, are incapable of adequately engaging in the process, and actually writing the grant proposals. This is an awareness and capacity development challenge.”

Relative to other applicants, Jewish applicant nonprofits are connected to a supporting network of organizations that help alleviate these challenges in three particularly advantageous ways:

- Information dissemination – Several Jewish community organizations dedicate substantial amounts of time and human capital toward communicating with their constituencies about the NSGP’s existence, encouraging them to apply, and describing the features of a competitive application and the deadlines to follow when applying.

- Technical assistance – Submitting a NSGP application requires substantial time and effort. Several organizations alleviate the time and energy costs associated with some of the most onerous aspects of the application process. This includes providing resources for identifying the level of risk an institution may face, easy-to-use template Investment Justification forms to fill out, and access to community security professionals who can conduct risk assessments as well as review parts of an application.

- Alleviating financial costs associated with NSGP participation – Since the NSGP is a reimbursement program, that means applicant entities must first purchase a good or service before receiving funding to pay for it. As a result, applicants are forced to incur short- to medium-term financial costs, presenting an additional difficulty for financially constrained entities. The Hebrew Free Loan Society, a nonprofit organization providing non-sectarian zero-interest loans to those in need, has a special program called the Security Infrastructure Loan Program. It is specifically designed for Jewish institutions in the wider New York City metropolitan area to help them pay for these expenses. According to a Hebrew Free Loan Society representative the author spoke with, similar efforts at varying levels of scale exist among Jewish communities in other parts of the United States.

The fourth factor affecting NSGP sub-award dissemination is the terrorist threat landscape confronting the United States. Ideologically motivated violence, in terms of both perpetrators and victims, is not limited to any particular group of people. That said, in terms of targets, events over past several years, including the incident in Colleyville, underscore the salient role antisemitism plays in mobilizing extremists from across multiple ideologies into violence.

While ideologically motivated violence threatens houses of worship and nonprofits associated with many different communities, Jewish institutions appear to be at a disproportionately high risk of attack. For example, an October 2020 study by the University of Maryland’s START Center found antisemitic attackers constituted just over 10 percent of all bias-motivated violence in their dataset, but “comprise over a third (38.1%) of the individuals in the data who planned or committed mass casualty attacks.” Combined with legislative history, programmatic design, and the impact of supporting institutional networks, Jewish entities’ heightened risk profile explains their preponderant share of NSGP sub-awards.

Finally, many institutions choose not to apply. In addition to the logistical challenges associated with applying for the NSGP, some entities do not see a need to apply for the NSGP because implementing security measures, such as installing reinforced doors, surveillance systems, or armed personnel at entrances, may feel off-putting and unwelcoming to congregants and non-congregants alike. Others believe security measures are important, but they have their own internal resources they can draw upon without feeling the need to receive financial assistance from the federal government.

Others have expressed opposition or strongly suggested caution about the program on civil liberties grounds, arguing that the NSGP could be a potential backdoor to surveillance or having congregation information used to inform future immigration enforcement operations. To alleviate the latter set of concerns, FEMA updated last year’s FAQ document for the program, explicitly clarifying there were no requirements for applicants to share information with law enforcement and that the security review part of the process was “limited to the organization’s name and physical address, as submitted by the nonprofit.”

Recommendations

Although there is high demand for the NSGP’s resources, and the program holds significant promise to serve the security needs of nonprofits and houses of worship, the program is far from realizing its full potential. Demand for funds is much higher than supply, funding has clustered in ways that have not reached many under-served communities’ institutions, the application process is time- and resource-intensive, the program explicitly prioritizes certain security measures over others, and data to inform policymaking and program design is often incomplete or non-existent. Several steps could be taken to make the program more accessible:

- First, increase funding for the program sub-awards. Demand for the NSGP vastly outstrips supply. In FY 2021 only 48% of total applications reviewed by FEMA were approved. However, some advocates familiar with the program claim that “80 to 90 percent” of the applications could have been approved had sufficient funds been available. If true, then taking this information at face value, this analysis recommends increasing the program’s sub-award budget to $360 million in FY 2023 in an effort to better meet that demand.

- Second, increase resources for running the program. In addition to whatever yearly budget is allocated by Congress for NSGP sub-awards, an additional 10% should be given specifically for the management of the NSGP. One-third should be given to the office of the program manager for costs associated with the management and oversight of the program, including line items such as outreach and hiring full-time FEMA federal civil servants dedicated to the operation of the NSGP. The other two-thirds should be given to SAAs to assist in covering management and administrative costs associated with their roles in operating the program.

- Third, policymakers need to improve the NSGP’s ability to assist nonprofits in under-served communities. Government officials are urged to closely re-examine the scoring point multiplication factor that has historically favored faith-based entities over secular ones. They are also strongly urged to increase the allowable amount of overhead cost percentages for “minority-owned” and operated institutions from 5 to 10 percent. This helps otherwise under-served and under-resourced institutions better defray the costs associated with applying for and managing the sub-award’s 36-month period of performance. Policymakers also are urged to implement the 2019 Faith-Based Advisory Council report’s recommendation to create an office within the Department of Homeland Security, to provide technical assistance for nonprofits engaged in the NSGP and wider the FEMA non-disaster grant application processes.

- Fourth, more data on NSGP sub-awards is needed. As noted earlier, data from USAspending.gov is far from complete. In some cases, the Department of Homeland Security and members of Congress make some annual NSGP sub-award recipients lists available, but this has not been consistent across all years. Lawmakers and Homeland Security policymakers are urged to make annual NSGP sub-award recipient lists publicly available for all fiscal years, while ensuring that sensitive personal identifiable information remains confidential. They are also urged to make efforts toward providing documentation of NSGP sub-awards in the USAspending.gov portal as complete and up-to-date as possible.

- Fifth, encourage a more holistic approach to security upgrades. The NSGP explicitly prioritizes physical measures that “harden” a potential target such as bullet/bomb-resistant doors and windows, surveillance systems, and entry/exit systems. While this may prevent some potential attacks, it will do little to prevent incidents like the Colleyville, Texas, hostage-taking crisis. DHS officials are urged to rethink and revise the NSGP to give equal weight to training for response and mitigation of rampage attacks and active shooter events, not just equipment and other physical security upgrades.

- Sixth, provide funding for monitoring and evaluation research of the NSGP. While the NSGP has strong support in Congress and among many nonprofits, it remains an under-studied program. Understanding its full potential of benefits and full awareness of drawbacks is difficult in the absence of systematic empirical examination. Policymakers are urged to provide research grants to rigorously study the federal NSGP and similar state programs.

Alejandro J. Beutel is a nonresident fellow with the New Lines Institute who studies non-violent and violent extremist far-right and Islamist movements. Beutel is a former Senior Research Analyst at the Southern Poverty Law Center and a former Researcher for Countering Violent Extremism at the University of Maryland’s National Consortium for the Study of & Responses to Terrorism. He is pursuing a PhD in Criminology and Criminal Justice at the University of Massachusetts at Lowell.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of the New Lines Institute.