Editor’s Note: This Net Assessment is part 12 of “ISIS 2020” – a series of briefings about the current status of the Islamic State by authors from different parts of the region. It is published by the Newlines Institute‘s Nonstate Actors program. Parts one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine, ten, and eleven were released on April 28, May 5, May 12, May 19, May 26, June 2, June 4, June 9, June 16, and June 23, respectively.

Introduction: Reliability of Information about the Islamic State

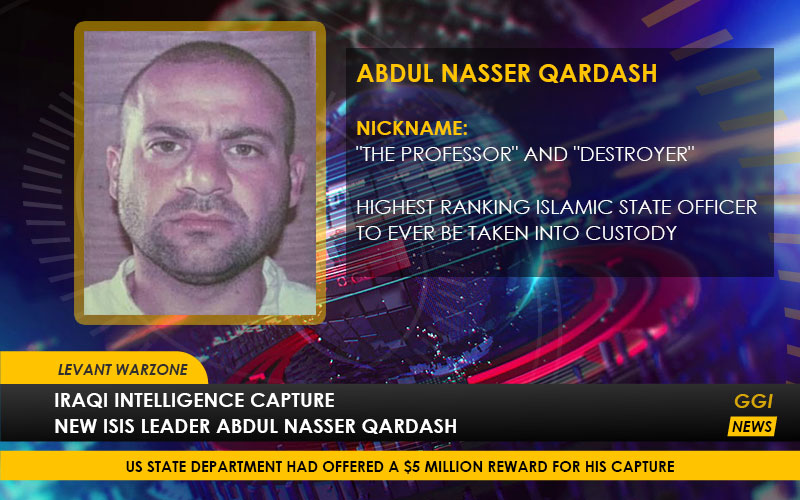

One of the problems facing analysis of jihadist groups is that they are clandestine organizations by nature, so there is a large gap between the data available to researchers and the potential amount of data in the real world. Research also heavily depends on news of the activities of these groups from the propaganda they themselves put out. It is hard to imagine what tracking the Islamic State would look like if outsiders were cut off from the daily news bulletins the group puts out and the weekly issues of the al-Naba newsletter. Statements by imprisoned Islamic State members can present compelling data but also potential pitfalls. A recent Newlines Institute interview with senior ISIS leader Abdul Nasser Qardash offers rich insight into ISIS’ beliefs and planning during former leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi’s reign. However, policymakers and analysts should be careful about drawing definitive conclusions from the interview about current ISIS operations and strategy.

Observers tend to regard as inherently invaluable evidence such as internal documents, testimonies from defectors, and interviews with captured members and officials of these organizations. At the same time, they may overemphasize an alternative line of evidence to which they gain access and treat it as revealing the “real story” of a jihadist group without examining reliability, circumstance, and motivations. It is thus always necessary to compare any new information that emerges in these mediums with the other lines of evidence available. Another question is whether the new information offers real insights for policymakers and strategists or deliberately obfuscates reality as opposed to revealing it.

It is with these points in mind that we should approach the Qardash interview. Qardash, currently in Iraqi custody, reputedly held the position of amir of the Delegated Committee (the general governing body overseeing the Islamic State) and was al-Baghdadi’s deputy. Some immediate general caveats regarding the interview are that Qardash is in custody and may not necessarily have the complete freedom to speak. Further, Qardash was not known to outsiders generally prior to Hashimi’s interview with him, making it difficult to gauge his motivations and relations with other figures in the organization. He also may not have been able to recall all details of his time with the organization correctly.

The interview presents some interesting information on the ideological influences and workings of the organization that can be corroborated by other existing lines of evidence, but Qardash also makes some dubious claims, and the overall value of his testimony is primarily historical. He also may well retain his commitment to ISIS’ ideology and therefore an incentive to embellish, hold back, or fabricate information, limiting the interview’s value to policymakers.

Ideological Influences

In his interview, Qardash discusses ideological influences on the Islamic State in the context of the group’s rise. He asserts that the lectures of Abu Ala al-Afri served as an “ideological reference for the organization” and a “basic internal and guiding system for them.” There is definitely some truth to these claims. Al-Afri, also known as Abu Ali al-Anbari, was head of Islamic State predecessor organization Majlis Shura al-Mujahideen, and he later served as a deputy to al-Baghdadi and eventually became head of Diwan Bayt al-Mal, the Islamic State’s financial department . He also had a prolific output of books and lectures, such as a book on the necessity of jihad, an attack on the Shia in general, and “lessons in faith preparation,” which were given to detainees in the prisons of Abu Ghraib and Camp Bucca, where many of the group’s founders and leaders, including al-Baghdadi himself, were once jailed.

It is significant that al-Afri continues to be revered both by the Islamic State members and supporters and by a more moderate group that defected from the organization, came to oppose Baghdadi’s leadership of the Islamic State, and opposes the current leadership of Abu Ibrahim al-Qurashi. The Turath Ilmi foundation, a dissident-run media organization that has angered ISIS by publishing information on its internal troubles and works without the permission from the organization, published the full biography of al-Afri written by his son, not to discredit him but to commemorate him as one of the “good” figures of the Islamic State who should be accepted by God as a martyr. More recently, the Structure of the Caliphate foundation — an outlet that supports the Islamic State — published an Arabic translation of al-Afri’s “lessons in faith preparation,” which he originally gave to his followers in the Turkmen language, indicating that he had built a following among Sunni Turkmen early on during the Iraqi insurgency from the Tel Afar area in northern Iraq. The lessons discuss matters such as intention in faith, prayer, and fasting.

Much of what we now know about al-Afri’s role within the organization had not been known before ISIS started to publish details about him after his death near the Syrian-Iraqi border in March 2016, including the fact that he had been head of Majlis Shura al-Mujahideen, a fact the U.S. counterterrorism officials had not realized even though he was in U.S. captivity shortly after he assumed that role in 2006.

Another interesting influence Qardash highlights in the interview is that of Sayyid Qutb on the media office. Watchers of the group have justifiably focused on influences such as Wahhabi ideas of “nullifiers of Islam” — a set of ten acts that make a Muslim a disbeliever or apostate — on basic Islamic State ideology and creed. The question of Qutb’s influence is one that merits further exploration given that it does not overlap neatly with ISIS’ ideology. For instance, Qutb is cited several times in the internal Islamic State history book “Stations and Lessons from the Sira and History,” stressing the repeating nature of history with the prophets documented in Islamic texts and the importance of holding up monotheism, and not compromising on the call to monotheism. This is significant since ISIS is typically portrayed by analysts and researchers as a group that adheres only to medieval theological sources rather than modern Islamist thinkers like Qutb.

Inner Workings and Structure

In the interview, Qardash also references some internal events and structures that are corroborated in other lines of evidence. For instance, he references the group’s execution of its own shariah judge Abu Jafar al-Hattab and others on the grounds of “extremism” in the Islamic State’s eyes for the doctrine of declaring as infidels people who accept ignorance as an excuse in matters of creed and apostasy (known in these circles simply as “excusing in ignorance”).

On the administrative side, Qardash’s claim that there was one Delegated Committee in Iraq and another in Syria before the two were merged is interesting because it had tended to be assumed that there had only been one Delegated Committee serving as the executive body of ISIS. For context, the Delegated Committee used to be called the General Governing Committee. In various internal documents, obtained by the author, one can find references to the “Delegated Committee in the eastern wilayas” (i.e. the Iraqi wilayas) and in an earlier stage, the General Governing Committee in “al-Sham” (i.e. the western wilayas) requested a report on repentance practices in the eastern wilayas.

Dubious Claims

Other claims Qardash makes in the interview could be interpreted as dubious or inaccurate by close observers of the group. The reason for those apparent inaccuracies is not necessarily deliberate deception. His recall may be imprecise, or he may misspeak. Another way of examining such claims is to understand them as an expression of how the situation was seen from within the organization, rather than as a statement of technical facts.

For instance, Qardash talks about the Islamic State’s reviews of its approach or ideology and says that these were only carried out after the defeats in Kobani and Sinjar in 2015. While it is true that a review of the group’s tactics became necessary in light of the defeat in Kobani that saw large numbers of fighters wiped out in coalition airstrikes, Qardash’s statement may be misconstrued to mean that the Islamic State did not try to consolidate or review matters of ideology. In fact, a highly significant controversy arose when the Delegated Committee issued a statement on matters of doctrine in May 2017 that was interpreted by the more “moderate” trend as a concession to extremists. That statement was then cancelled by the Delegated Committee in September 2017, with a series of lectures then issued on matters of doctrine to correct the prior errors.

There also appears to be confusion around the killing of Jordanian Air Force pilot Muath al-Kasasibah, who was burned alive on video in 2015 after crash-landing in Syria. Qardash claims that Abu Muhammad al-Furqan, an ISIS Shura Council member who once headed the organization’s media department, and Abu Luqman al-Kuwaiti, an otherwise obscure personality, issued the fatwa to kill al-Kasabeh, but documentary evidence shows that the fatwa partly justifying the measure as retaliation in kind was issued under the imprint of the head of the Research and Fatwa-Issuing Commission, which was most likely headed or heavily influenced by Turki Binali at the time. Binali was head of the Office of Research and Studies, a rebranded successor to the Research and Fatwa-Issuing Commission. Qardash suggests the fatwa to burn al-Kasasibah alive was really the work of two other officials within the organization, both dead.

In terms of administration, it is inaccurate on the surface to claim that there is “no organizational or clear leadership structure” to link the Islamic State’s branches and wilayas outside Iraq and Syria. In fact, the Islamic State created an administrative body to oversee relations with the “distant wilayas” (i.e., the provinces outside of Iraq and Syria). This administration effectiveness in managing relations with the affiliates is another question, as when the distant provinces administration had to deal with issues of insubordination from members of the Yemen-based affiliates, but there is a clear administrative link between the center and the affiliates. This could be what Qardash was trying to say: Although there might be an institution on paper, the managing of the distant affiliates has been an ad hoc process.

Policy Relevance

It has not been the aim of this article to scrutinize all of Qardash’s claims. That would only make for tedious reading. Rather, the preceding sections provide a useful survey of how his words are a mixture of some truths that provide interesting insights on the ideology and the workings of the organization and some apparent falsehoods or errors that may arise for a variety of reasons. This is why the interview should be taken with a grain of salt, as the Newlines Institute wrote in its preface.

The interview offers insights into the Islamic State’s thinking, messaging and workings, particularly on a historical level, during the years of Baghdadi’s control of the organization. But Qardash’s information is naturally dated to before his capture — for example, he is uncertain of the identity of the group’s current leader — which decreases the interview’s relevance for policymakers today as they deal with the ever-evolving challenge of the Islamic State.

Aymenn Al-Tamimi is a Senior Fellow with the Newlines Institute. Tamimi is a doctoral candidate at Swansea University, where he focuses on the role of historical narratives in Islamic State propaganda. His research focuses primarily on Iraq, Syria and Jihadism. He established the Islamic State Archives project in collaboration with Jihadology for the storage of internal Islamic State documents and files obtained from Iraq and Syria. Follow him on Twitter @ajaltamimi.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of the Newlines Institute.