To recognize the impact of conflict on women and girls and reaffirm “the important role of women in the prevention and resolution of conflicts and in peace-building,” the U.N. Security Council adopted Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace, and Security in 2000. Resolution 1325 – along with the nine subsequent resolutions that comprise the Women, Peace, and Security (WPS) agenda – seek to recognize the roles that women, as half of the population, play in peace and security, both as victims and as actors, and provide a framework to bolster their participation in achieving sustainable international peace and security.

While the WPS agenda has made some positive progress toward its goals, the agenda has largely been siloed from broader U.S. efforts toward global peace and security as “women’s issues.” Across the U.S. government, the responsibility for integrating gender perspectives and the WPS agenda has been primarily given to the few departments and offices with the words “gender” or “women” in their title. As a result, the terms “gender” and “women” have effectively been conflated, “as if men, males, and masculinities were … nothing to do with gender at all.” This limited understanding of gender within policy spaces hinders the transformative potential of the WPS agenda as a policy tool by burdening women with solving issues of their own oppression and victimization, as well as obscuring the intersectional dynamics of gendered experiences that make “women’s problems” a cross-cutting issue that is relevant to everyone. The conflation of the terms also masks the larger patriarchal structures that operate at all levels, restricting WPS efforts to the actions that individual women can take within the confines of a global patriarchal system, which in turn prevents the agenda from serving as a useful tool.

2023 has been the single worst year for conflict since 1994, with over 238,000 conflict deaths as of June, a number which has grown with the intensification of ongoing conflicts and the onset of new conflicts, such as the Israel-Hamas War. The integration of masculinities into U.S. implementation of the Women, Peace and Security Agenda is necessary to improve the agenda’s efficacy as a tool for U.S. foreign and domestic policy. To effectively do so, it is vital that U.S. WPS policy and programming: consider masculinities as part of gender analysis; understand how masculinities shape and are shaped by global and domestic challenges such as armed conflict, violent extremism, and rising authoritarianism; and grapple with the structural issue of deeply rooted harmful masculinities within U.S. institutions.

Gendering Men and Boys

To dismantle the structures that produce and perpetuate violence, insecurity, and gendered harms that are experienced by women, men, and those with diverse gender identities, policy efforts must be founded on recognition of and considerations for men and boys’ gender. We define the term “gender” as the “socially constructed identities, attributes, and roles” of men, women, and gender non-conforming people that result in social, cultural, and economic hierarchies between and among people of all genders. The term “masculinities” recognizes that there are many socially accepted (and less accepted) ways to be a man that shift across different cultural and societal contexts.

Masculinities is a critical framework that can contribute to the implementation of the Women, Peace and Security Agenda by allowing a space for men’s identities to be interrogated and understood in their cultural context. Recent years have seen an increase in academic and policy discussions about accounting for men and boys in the WPS agenda while correcting for historical inequalities and marginalization of women and girls within the peace and security field. A more inclusive gender analysis that considers men and masculinities illuminates the ways in which men are also inhibited by strict patriarchal norms – such as emotional control, self-reliance, and heteronormativity – around their gender identity and expression, as well as how masculine gendered expectations and men’s lived experiences can increase radicalization, perpetuate cultures of violence among men (including against women), and leave lasting physical and mental scars.

By recognizing women’s issues as one piece of a comprehensive gender analysis, and by labeling men and boys as gendered beings, the WPS agenda becomes accessible and relevant to addressing foreign and domestic policy issues in new ways. The recently released 2023 U.S. Strategy and National Action Plan on WPS makes some progress toward recognition of men and boys’ gender in its brief consideration of “masculinity” within its definition of gender-based violence. However, more inclusive and comprehensive gender analyses and considerations for the gendered impacts of U.S. domestic and foreign policies that recognize masculinities are needed to accelerate progress toward sustainable peace and the fulfillment of U.S. commitments to the WPS agenda.

War and Conflict

Integrating masculinities into U.S. WPS policy and programming can help U.S. officials better understand the ways in which certain constructions of “manhood” and norms around masculinity drive militarism and conflict. War is socially constructed as a male domain across cultures, with many rites of passage and benchmarks of “manliness” that boys must achieve having evolved around the qualities of the ideal warrior. Indeed, within Western society, adjectives such as violent, aggressive, dominant, and heroic are often evoked in various interpretations of what it means to be masculine. Men make up the majority of actors that start, fight in, and end wars, meaning that militarized masculine ideals shape the way that conflicts are fought by structuring the “boundaries of acceptable violence” and ascribing value to different tactics of warfare. As the nature of war changes throughout the 21st century with technological advancements such as autonomous weapons, space technologies, and nuclear escalation, the future of international peace and security may be heavily dependent on disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration efforts that are designed to restructure militarized masculinities with the ideals of restraint, diplomacy, and peacemaking replacing the traditional masculine values that perpetuate conflict.

The societal norms and values ascribed to particular interpretations of masculinities not only shape the international war system but also mold violent behavior carried out by individuals and armed groups in fragile and conflict-affected settings, including gender-based violence such as rape, domestic violence, and conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV). While the perpetration of sexual and gender-based violence in war ranges from the opportunistic behavior of individuals to an explicit weapon of war used by armed groups, it is commonly agreed that “[wartime] rape is a product of warped (yet normalized) militarized hegemonic masculinity.” Rape in war exists on the continuum of sexual violence and does not occur in a vacuum. CRSV is driven by factors that exist during peacetime, including sexist attitudes, patriarchal societies, and the belief that “women exist for the sexual gratification of men.” As violence against women cannot be accurately divided along the timeline of peace, conflict, and post-conflict periods, efforts to protect women from CRSV must stem from an understanding of the structural patriarchal inequities that drive gendered vulnerabilities in all settings.

Patriarchal values also underpin the perpetration of conflict-related violence against men, which is overwhelmingly committed by other men and is often overlooked in policy discussions related to CRSV. This omission of consideration for male victims of CRSV stems, in part, from a limited understanding of what acts constitute crimes of sexual violence. Men can, of course, be victims of the more readily accepted forms of CRSV like rape, sexual slavery, and forced sterilization. However, the forms of sexual violence that are more commonly perpetrated against men than against women – such as “sexual humiliation, punching or electroshocks to the genitals and secondary victimization stemming from being forced to watch the rape of wives” – are often framed as torture and cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment, which conceals the specific harm and affront to human dignity that sexual violence presents. The perpetration of CRSV against men can be viewed as a means through which dominance and power can be established and communicated, in which the victim is “feminized” and therefore devalued within the patriarchal gender hierarchy. Male victims of sexual violence often fear being shamed and stigmatized, meaning these crimes are significantly underreported, hindering progress toward policies and programs to prevent and address this pervasive but misunderstood form of CRSV.

Masculinities and Violent Extremism

As most violent extremists are men, efforts to prevent and counter violent extremism, both domestically and internationally, can be bolstered by improved considerations for the experiences and vulnerabilities experienced by men. Even as women’s equality has increased in many societies, the masculine ideal that a man’s role is to be a leader, provider, and protector to their family has largely persisted. While these values of manhood and fatherhood are mostly peaceful and can be socially reinforced as nonviolent, they can equally be manipulated into violent manifestations of masculine norms. Poor socioeconomic conditions, conflict, and high levels of insecurity make it harder for men to fulfill these roles and expectations. Violent extremist organizations have become adept at utilizing masculinities for recruitment and propaganda purposes, often promising economic opportunity and physical security, as well as other markers of manhood such as marriage, social status, and sexual gratification. With few other options through which to achieve what is expected of them, engaging in violence and terrorist activity becomes “a rational choice for men.”

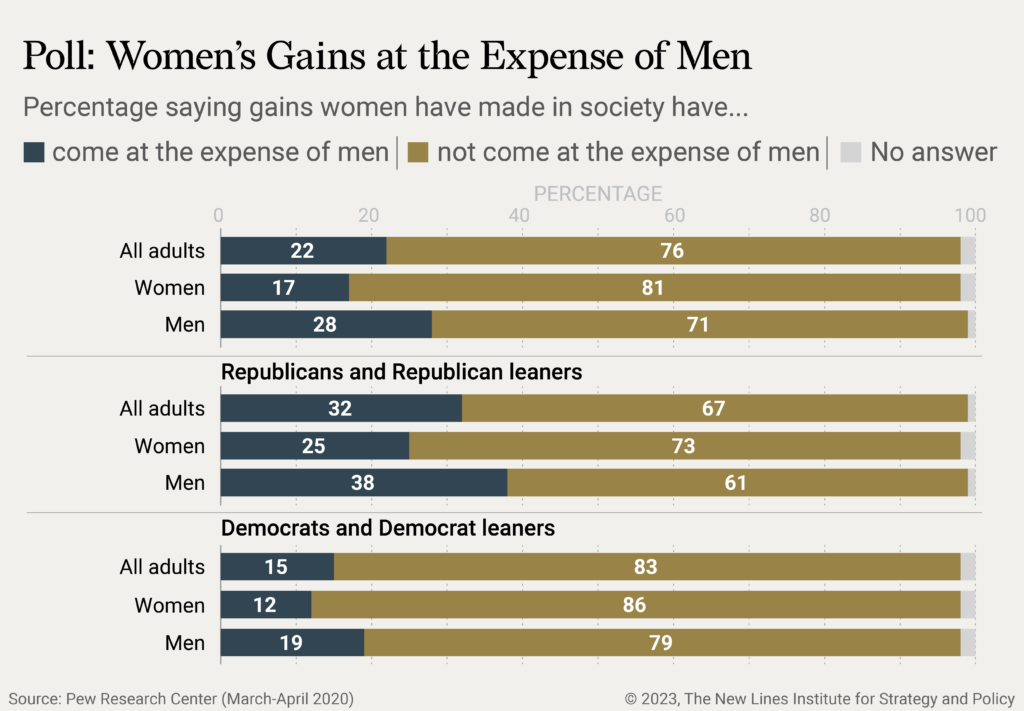

Men’s involvement in terrorist activities may also be driven by a perceived loss of supremacy or status, as the progression of gender equality may be seen as a “zero-sum game” in which men have to lose rights and privileges in order for women and minorities to gain them. Extremist organizations and terrorist groups have, in turn, become skilled at manipulating masculinities and the disaffection of individual men into an effective recruitment tactic by glorifying hypermasculinity and vilifying feminism and women’s empowerment as a “net negative for society.” Gender identity and ideology is connected to violent extremism; misogyny and hostility toward women are common elements of both far-right and Islamist extremist rhetoric.

While the 2023 U.S. Strategy and National Action Plan on WPS recognizes the links between misogyny and domestic extremism, it does so only in the context of online spaces. Male perpetrators of terrorism very often have histories of interpersonal and domestic violence against women and girls. If the government and related agencies do not integrate gender analysis into their efforts to counter and prevent violent extremism (C/PVE), efforts to prevent and counter domestic terrorism will be incomprehensive and ineffective in identifying potential perpetrators, identifying potential victims, and countering radicalizing rhetoric promoted by terrorist organizations. However, it is important to recognize that even in settings where violent extremism is common, most men are not engaged in these groups, and many men globally advocate for nonviolence and for positive masculinities. U.S. C/PVE policy and programming must recognize this and seek not only to demonstrate the negative consequences of engaging in violent extremism but also to promote alternate, more positive pathways toward achieving the norms of manhood.

Masculinities and Threats to Democracy

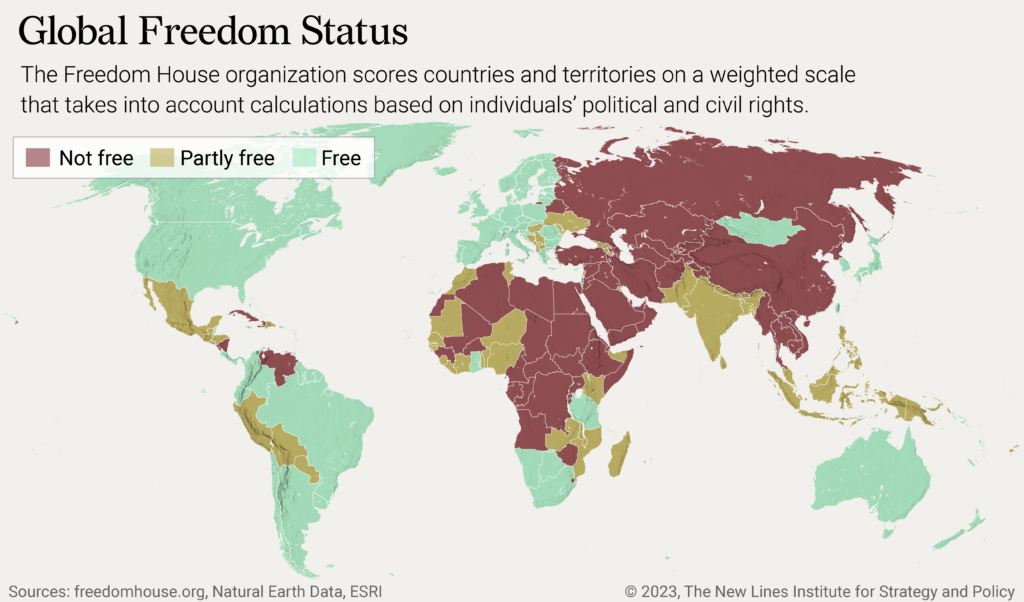

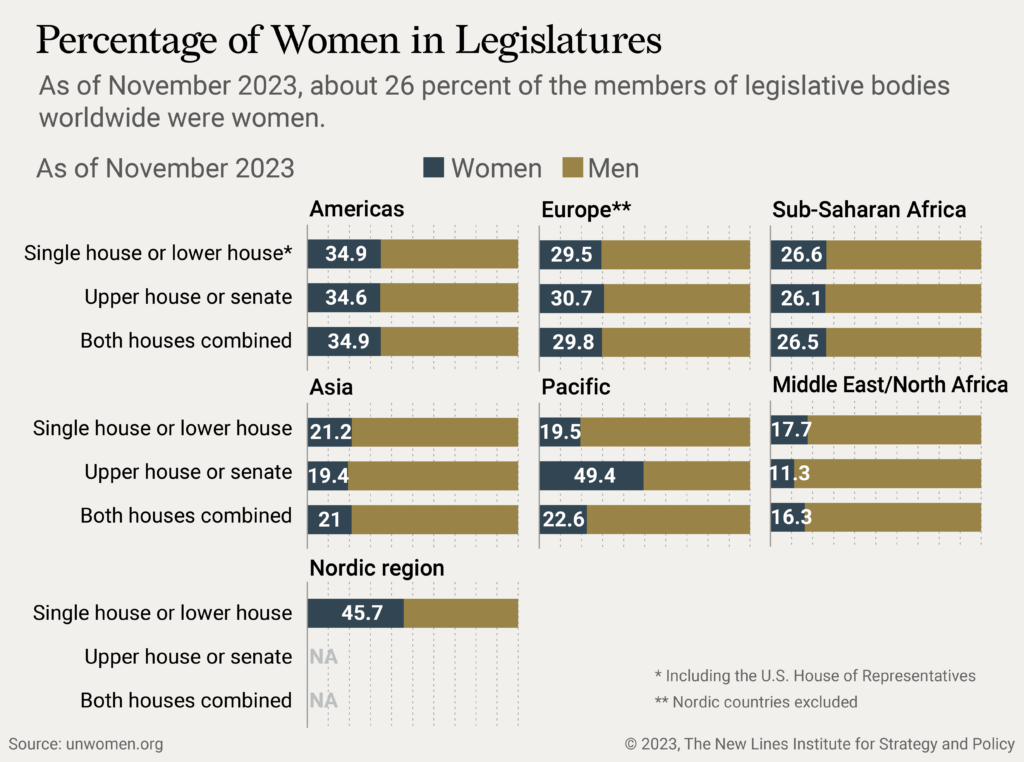

Recent years have been “marked by a wave of hollowing and backsliding of democracies” around the world, with 80 percent of the world’s population living in “partly free” or “not free” countries. As this backsliding occurs simultaneously with the rollback of women’s rights, recognition that “misogyny and authoritarianism are not just comorbidities but mutually reinforcing ills” is growing in academic and policy spaces. Political spaces all around the world continue to be dominated by men, leading to an idealization of traditionally masculine traits among world leaders. Political actors are often implicitly tasked with proving that they are “man enough” for office and emasculating their opponents to gain advantage. In 2016, then-U.S. presidential candidate Donald Trump defended himself against implications made by Sen. Marco Rubio about the size of Trump’s genitals, stating, “He referred to my hands: ‘If they’re small, something else must be small.’ I guarantee you there’s no problem.”

The growth of strongman geopolitics in the 21st century is driven, in part, by cultural backlash against progress toward gender equality and a perceived shift in status quo that threatens cis-male supremacy. The hypermasculinity displayed by many autocratic leaders appeals to those who wish to preserve the patriarchal status quo that places masculinity as the supreme global power. Authoritarian leaders capitalize on fear – of immigrants, of minorities, of gender differences – to appeal to conservative and patriarchal gender norms, relegating women to roles such as wives and mothers while excluding them from public and political life in order to consolidate power through traditional societal hierarchies. Russian state-backed media has often been seen to combine conservative narratives about gender with “criticism of elites, the mainstream media, ‘identity politics,’ and … political correctness.” In order to counter rising authoritarianism, it is essential that policymakers have an adequate understanding of the role of masculinities in the “autocrat’s playbook.” Engagement of men in peace and security work must confront stereotypes of gender equality as a “winner-take-all” scenario in which men must lose for women to gain.

Attacks against women’s rights by political leaders are often the canary in the coal mine of rising autocratization, as several forms of misogyny are generally tolerated by most cultures around the world. Given that “the status of women is the status of democracy,” the WPS Agenda – as a tool for the acceleration of women’s political participation and protection – is integral in combating democratic backsliding. By focusing on the concept of masculinities, WPS policy and programming can counter the “crisis of masculinity” and anxieties that arise from the shifting of gender norms by demonstrating the ways in which gender inequality hurts individuals of all genders. This requires that WPS efforts revise the singular conceptualization of masculinities as dangerous to women to better understand how harmful masculinities are exacerbated by systems of oppression. Developing policies and programs that acknowledge the universal harm of patriarchy – as well as its role in upholding social, economic, racial, and colonial hierarchies – effectively delineates the role that men and masculinities have in achieving a feminist vision of a world “whose wealth and natural resources are shared by all.” This requires collaboration with local civil society organizations to effectively engage men and boys at the community level to promote positive masculinities and empower them as allies in efforts towards gender equality.

Structural and Institutional Militarized Masculinities

It has been the tendency of many policy engagements with issues of men and masculinities to grapple with more narrow issues of gender inequality and gender-based violence at the individual and community levels, rather than challenging structural hierarchies, inequalities, and norms within institutions. To be sure, these policy initiatives are valuable, but transformative change cannot occur by “only working with the topsoil” of a deeply rooted and pervasive structure that both shapes and is shaped by the construction of gender norms. Just as the war system is a male-dominated space, global security institutions are made up mostly of men, resulting in institutional cultures of “misogyny and gender bias that perpetuate gender inequality and cultures of impunity, while rewarding a very particular set of traditionally ‘masculine’ traits and behaviours.” The masculine values and norms embedded in security institutions lead to a preference for militarized approaches to security that drive increased militarization of both state and non-state actors, perpetuate the cycle of fragility, and legitimize violence at the communal and interpersonal levels.

Norms and ideas about masculinity in security institutions also drive relations between these institutions and civilians. Within military processes, “gender and different masculine models have been mobilized to legitimize and normalize violence on non-U.S. soil, while promoting fear and hatred of the enemy.” When these models are employed with broad strokes, maleness becomes a signifier of militant status, increasing the likelihood that civilian men are considered legitimate targets for militarized violence. Counterinsurgency operations carried out under the Obama Administration have been criticized for their use of signature strikes, a drone strike practice that uses observation of a person’s behavior to determine if they are or will be engaging in combat, that targeted “military-aged males.” In 2012, the New York Times reported that the procedure “in effect counts all military-age males in a strike zone as combatants … unless there is explicit intelligence posthumously proving them innocent. Both the gender essentialist ideas about the inherent violence of men and the practice of “othering” the enemy that are supported by militarized masculinities within security institutions cause innocent civilian men to be killed merely for being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Further, militarized interventions – particularly those that result in civilian casualties – serve as “one of the most devastating driving forces for terrorism and destabilization” by sparking resentment and distrust of the United States, which extremist groups capitalize on in their recruitment efforts. By addressing the ways in which security institutions uphold and shape masculine norms and ideals, defense and security operations can improve both protection standards to reduce civilian casualties and processes for redressing harm to the families and communities of civilian victims to prevent further radicalization.

Building a transformative national action plan on WPS through the integration of masculinities requires that efforts expand beyond changing individual behaviors. These efforts also must promote the sustainability of positive masculinities within contexts of conflict and fragility. This means U.S. monitoring and reporting mechanisms on WPS implementation must be able to assess short- and long-term progress toward confronting systemic inequalities as drivers of violence. For this progress to be effective, peace and security actors and institutions must look inward. U.S. defense and security institutions and actors must critically examine how they have been shaped by masculine norms and how they uphold gender inequality by rewarding traditional ideals of masculinity in their work.

The brief discussions of “socially constructed norms around masculinity” and the connections between online misogyny and domestic extremism in the 2023 U.S. Strategy and National Action Plan reflect some progress toward recognition of the gendered experiences of men and of the value of engaging with masculinities as part of WPS implementation. However, the limited explicit considerations for men and masculinities within U.S. WPS implementation, as well as growing international insecurity, indicate a need for the U.S. to engage with more nuanced perspectives on gender to confront the roots of violent masculine behavior and to effectively counter the links between masculinity and violence.

Policy Recommendations

- The U.S. government should expand on the considerations of masculinity and misogyny in the 2023 WPS Strategy and National Action Plan institutionalize holistic understandings of the manifestations of masculinities as a driver of insecurity and conflict.

- Agency-level policy and programming on WPS and gender equality should consider the gendered harms that men and male-presenting individuals face as an important component of adequately integrating gender perspectives into the work of the U.S. government to further its commitments to the acceleration of the WPS agenda.

- Understanding of the structural patriarchal inequities that drive gendered vulnerabilities in all settings should be integrated into interagency efforts to prevent and respond to CRSV and other forms of sexual and gender-based violence, particularly within the U.S. Strategy to Prevent and Respond to Gender- Based Violence Globally and the U.S. National Plan to End Gender-Based Violence.

- The U.S. Department of State, especially the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, should consider the role of masculinities within the process of autocratization and seek to counter the perceptions of the masculinity crisis to promote democracy globally through programming in collaboration with the Secretary’s Office of Global Women’s Issues and with USAID – specifically the Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment Hub and the Inclusive Development Hub.

- The Department of Defense, Department of State, and interagency efforts toward foreign and domestic security should commission a gender analysis of existing internal processes and policies that critically examines how organizational cultures, processes, and objectives have been shaped by masculine norms and how they uphold gender inequality by rewarding traditional ideals of masculinity in their work.

- USAID programming, education, and grant partnerships on C/PVE and violence prevention should seek to promote positive/peaceful masculinities through educating men on the ways in which conflict resolution and peacebuilding achieve the aims and ideals of manhood more effectively and sustainably than engagement in violent behaviors.

Kallie Mitchell is an Analyst for the Gender Policy Portfolio at the New Lines Institute. Prior to joining the New Lines Institute, Kallie was a Research Assistant for the Women, Peace, and Security Program at the International Peace Institute, where she focused on gender in U.N. peace operations and women’s participation in peace processes. She previously worked as an Assistant Project Coordinator with the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, where she led a research project on electoral assistance in transitional elections. Kallie also worked as a Research Associate at the Institute of Comparative and Regional Studies in Denver, co-authoring a U.N. Development Program report on inclusive governance for sustainable peace. She tweets at @kalliemitchell0

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of the New Lines Institute.