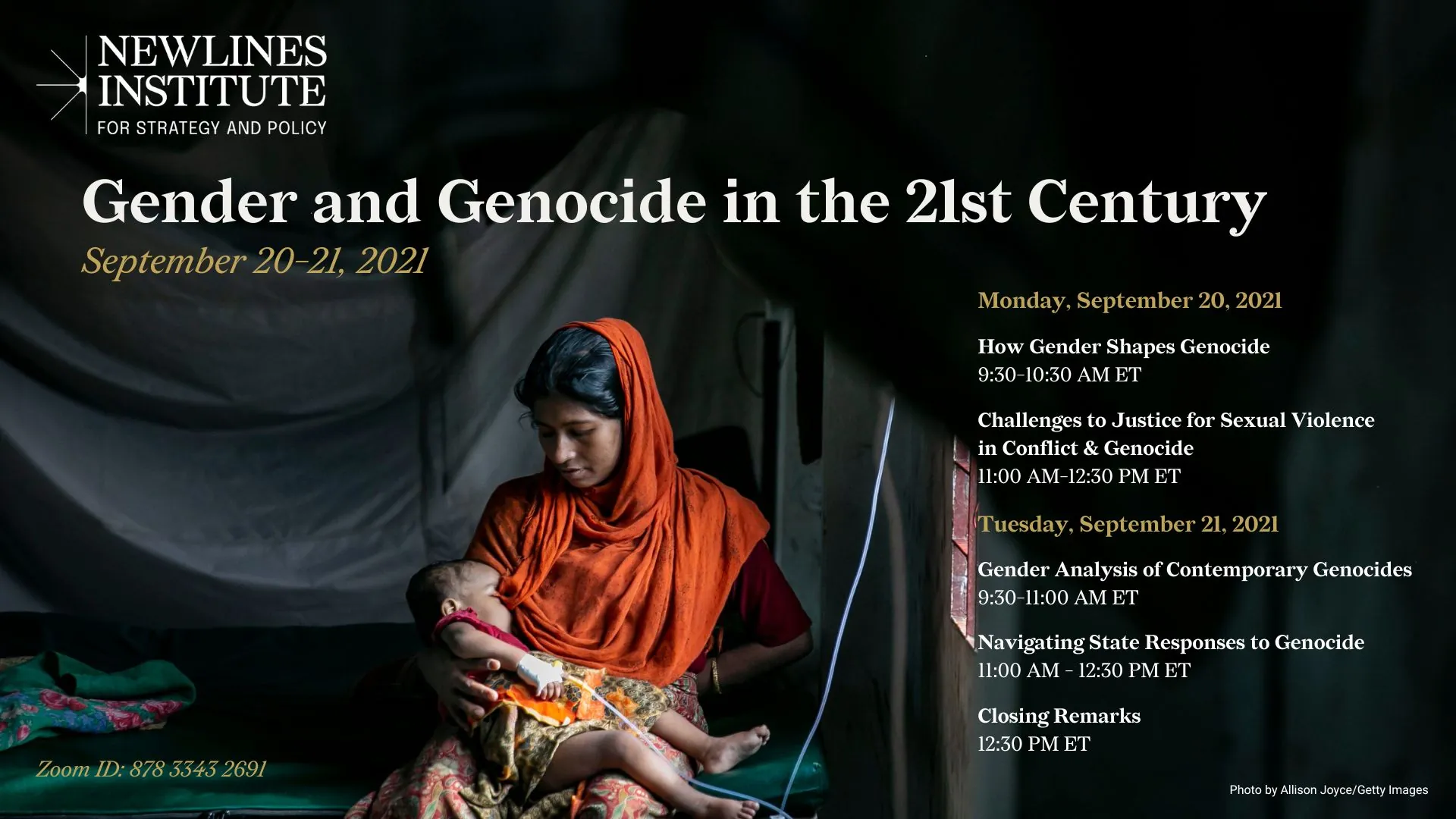

Gender and Genocide Conference

This two-day conference (September 20-21) convened legal, gender and genocide experts from around the world to discuss the four recent and/or ongoing asserted genocides of the Uyghurs, Rohingya, Yazidis, and Tigrayans. Our panels of experts examined State responses to genocide, challenges to justice for gendered crimes during conflict or genocide, and how the crime of genocide itself is gendered.

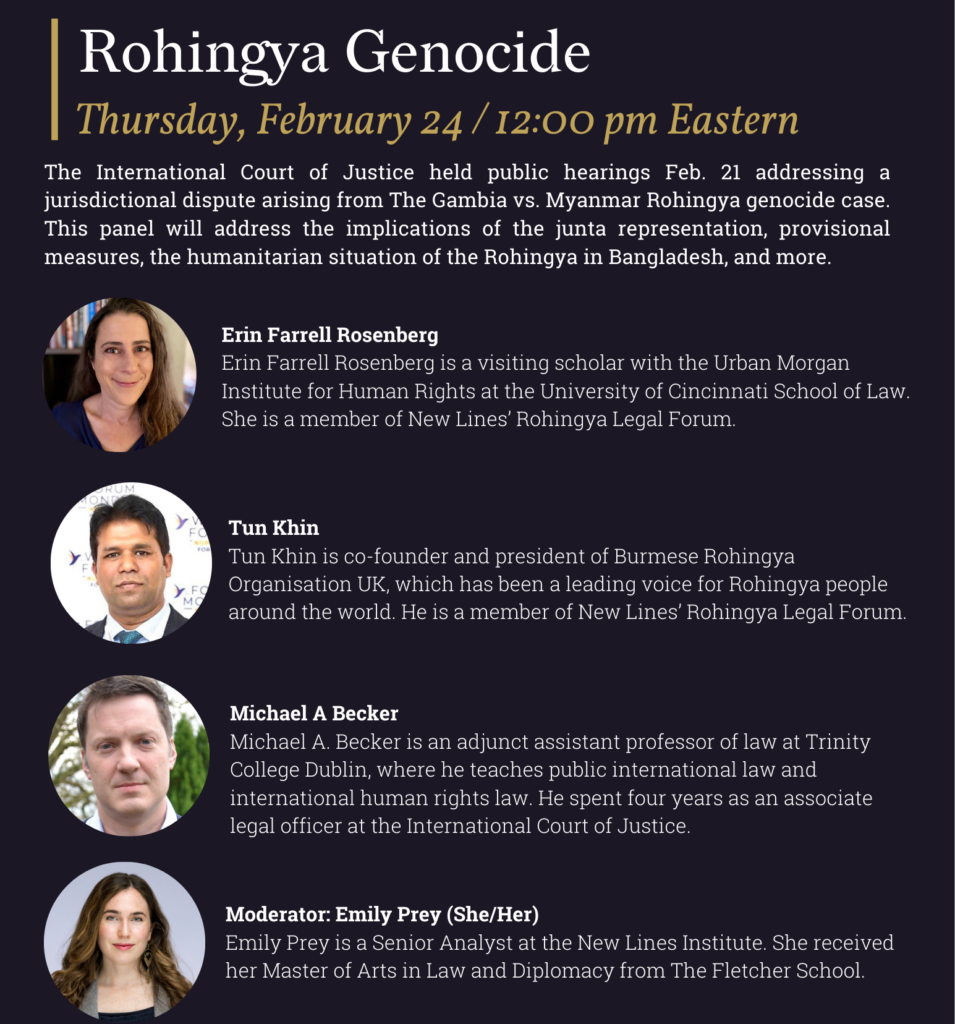

In 2014, ISIS soldiers massacred Yazidi men and boys, while the women and girls of child-bearing age were separated and distributed around the region to ISIS soldiers to be their slaves. In 2017, Myanmar’s military used rape and sexual mutilation as weapons of war against Rohingya women fleeing for their lives. As a result of the Chinese Communist Party’s coercive birth prevention programs targeting the Uyghurs and other minorities over the last several years, the estimated population loss from suppressed birth rates in southern Xinjiang alone ranges between 2.6 and 4.5 million. Beginning in 2020, armed forces in Ethiopia have used rape and sexual violence to inflict lasting physical and psychological damage not only on victims, but on whole communities. In this discussion, Akila Radhakrishnan and Emily Prey will examine the oft-overlooked, under-litigated gendered dynamics of genocide, why it is so crucial to engage in gendered analyses, and what state parties to the Genocide Convention, including the United States, can do to further these conversations

Rape has been an official war crime since 1919. It was added to the Geneva Conventions in 1949 and, in 1993, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia recognized rape as a crime against humanity. The first instance of rape being prosecuted as a war crime was in 1998 by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda. Despite these laws, perpetrators are almost never brought to justice. This panel will explore the challenges that survivors of sexual violence face in the fight for justice and accountability.

The recent and/or ongoing asserted genocides of the Uyghurs, Rohingya, Yazidis, and Tigrayans all include, prominently, allegations of sexual violence and, in some instances, prevention of births. But whether these are discrete prohibited acts or elements thereof, or should be viewed in composite or as evidence of the intent to destroy the group in whole or in part depends upon a fulsome analysis. This panel of experts will use gendered legal analyses to examine the similarities and differences of each manifestation, and whether or not there are elements that are more or less difficult to discern.

Although 152 states signed onto the 1948 Genocide Convention, it has become increasingly rare to see signatories do their duty under international law to prevent and to punish the crime of genocide – even in the face of overwhelming evidence. This panel of experts will examine why states reach the conclusion of genocide in some cases and not others, how much politics plays in genocide determinations, and look at specific state responses to the Uyghur, Rohingya, Yazidi, and Tigrayan genocides.